Any attempt to define the style of Ozias Leduc must first outline both his ethics and his thoughts. Born into a rural, francophone, Catholic culture in the second half of the nineteenth century, he synthesized the religious and moral values unique to a society that defined itself on the basis of positions promoted by Rome and Paris, but in a North American context, and adapted to a French-Canadian culture that was subject to British colonial rule. Leduc would draw on various aspects of this prevailing culture, which provided the stylistic, formal, and iconographic fundamentals of his work.

From Pantheism to Nationalism

A spirit of liberty, discipline, imagination, and dedication to study were some of the features that formed Leduc’s character as he grew up in an agricultural setting. These same concerns would also structure the progress of a career rooted in a belief in the value of work, the search for excellence, and the surpassing of the self. From The Three Apples (Les trois pommes), 1887, to his decoration of the Church of Notre-Dame-de-la-Présentation in Shawinigan, Leduc deepened his reflections on sanctification through everyday activities. His faith was evolving toward a form of pantheism that saw the divine presence manifested in the beauty of nature, including human nature. He never ceased to celebrate nature or to try to understand its laws. He also sought to deepen his knowledge of his surroundings and of humanity in order to translate them in his art in their most complex forms.

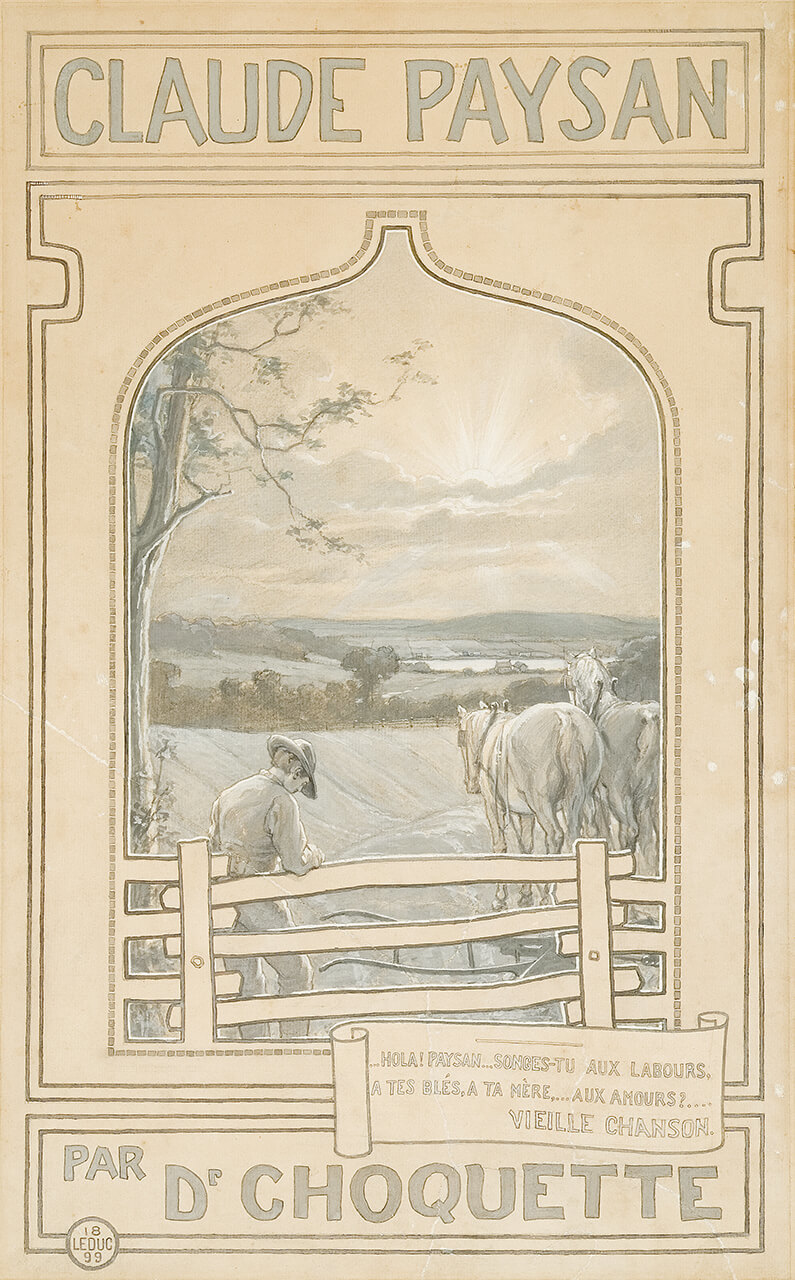

The Catholicism that characterized Leduc’s life was made up of many different strands, combining popular faith, neo-scholastic Thomism, and messianism. His childhood was dominated by the rites and ceremonies that imposed their rhythms on daily life, particularly rural life of the kind described in Claude Paysan (1899), the novel written by Ernest Choquette and illustrated by Leduc. It was a religion that sought to identify itself as a defining factor in the French-Canadian identity, and hoped to expand its creed throughout America. Leduc contributed to this clerical mission in the United States when he was commissioned to decorate several churches serving the French-Canadian diaspora in New Hampshire. But it was neo-Thomism, the renewed emphasis on the teachings of Saint Thomas Aquinas, that provided him with the idea that the proof of God’s existence in the universe is in the fundamental truths of the Good, the True, and the Beautiful. The thinking of the medieval theologian as interpreted by his followers proposes a blend of the beauty of nature, which is divine in essence, and the ideal of beauty pursued by art. The painter Napoléon Bourassa (1827–1916), whom Leduc admired, was a defender of these ideas, which he interpreted allegorically in his work titled The Mystical Painting (La peinture mystique), 1896–97.

What Leduc retained from his religious education was the founding principle of the mysteries of faith. The idea that Good co-exists with Evil was at the heart of his philosophy. The loss of the earthly paradise and salvation by manual and intellectual labour were at the root of his credo. The art historian Esther Trépanier associates this position with the Romantic and Symbolist movements, which attempted to reconcile the spiritual with the material world and rediscover the part of humanity that the modern world was said to have lost.

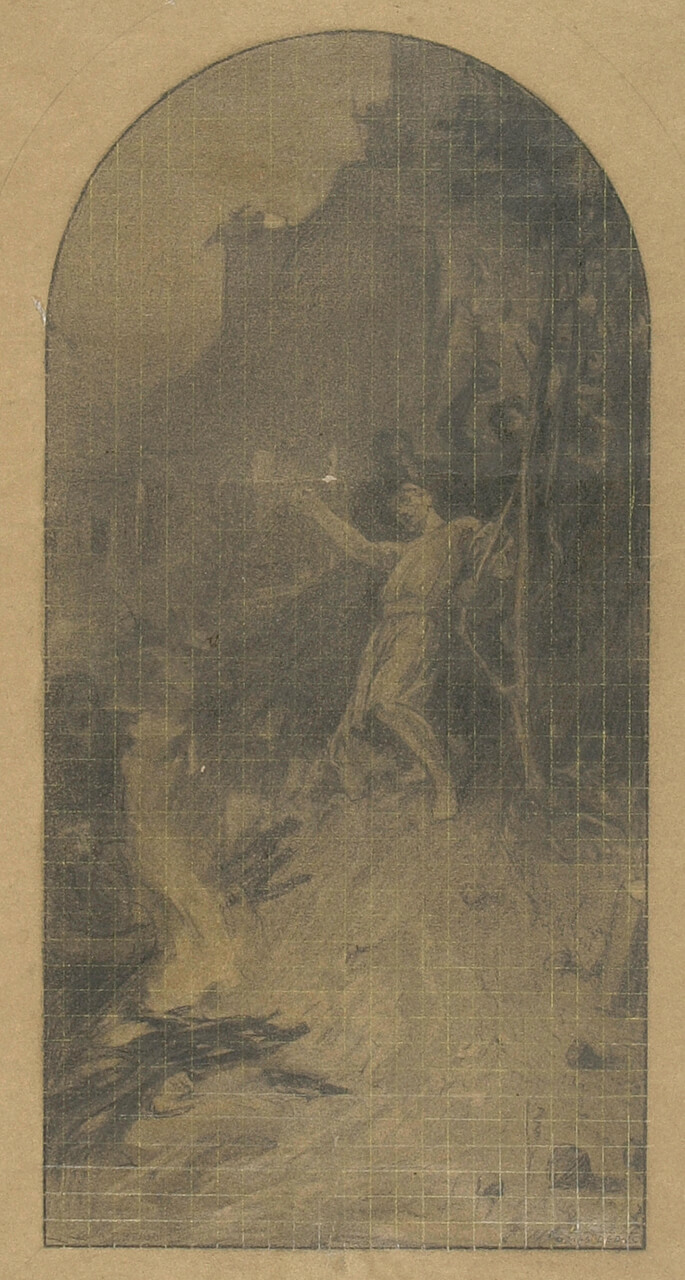

Leduc often invokes a lost state of paradise as an absolute to be regained. His art permitted him to project himself into the role of the Creator at the origin of a universe to be reimagined. For example, in his church decoration he proposed themes of the principal mysteries of faith: the fall and redemption, the loss and recovery of paradise. He preferred to paint images of the sacraments rather than devotions of the saints. When he was asked specifically to treat a hagiographic subject, such as The Martyrdom of Saint Barnabas (Le Martyre de Saint-Barnabé), 1911, for the church of the same name, he transformed what might have been a representation of the saint’s last moments into a movement between fall and ascension. The blessed saint, having been stoned and thrown into a fire, holds himself in a bodily position that combines gravity and levitation. His body is pushed down but seems to undulate, float, and rise up.

Liberal values modified the ascetic worldview of Quebec at the beginning of the century. French-Canadian people began to see themselves as unique in North American society and adopted the attitude of a resistant nation capable of imposing its values and practices on the continent. Leduc took a position between nationalism and internationalism, and celebrated the uniqueness of his corner of the world.

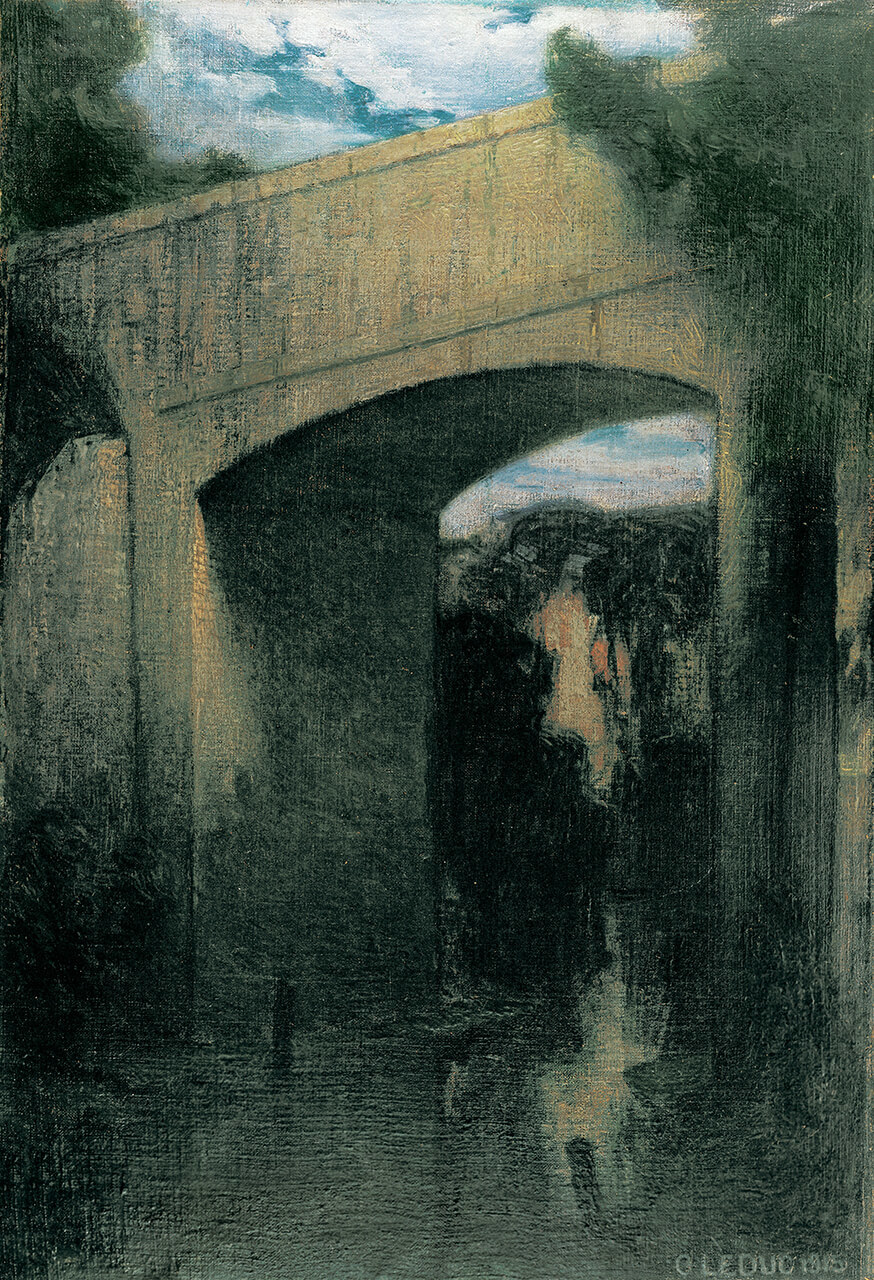

The iconography of The Concrete Bridge (Le pont de béton), 1915, can be situated within this current of his thinking. An enormous bridge takes up almost the entire foreground of the painting, covering most of the canvas. This symbol of connection takes on a disproportionate importance relative to the waterway it spans. It overwhelms the natural environment. Yet it looks somewhat like an eyelid over an open eye observing the landscape we can barely see in the background. It obstructs and at the same time inserts itself into nature. The modernity of the material, stated in the title, invites a reading of this work as a dominating contemporary construction in search of a balance with its surroundings.

Nature as Symbol

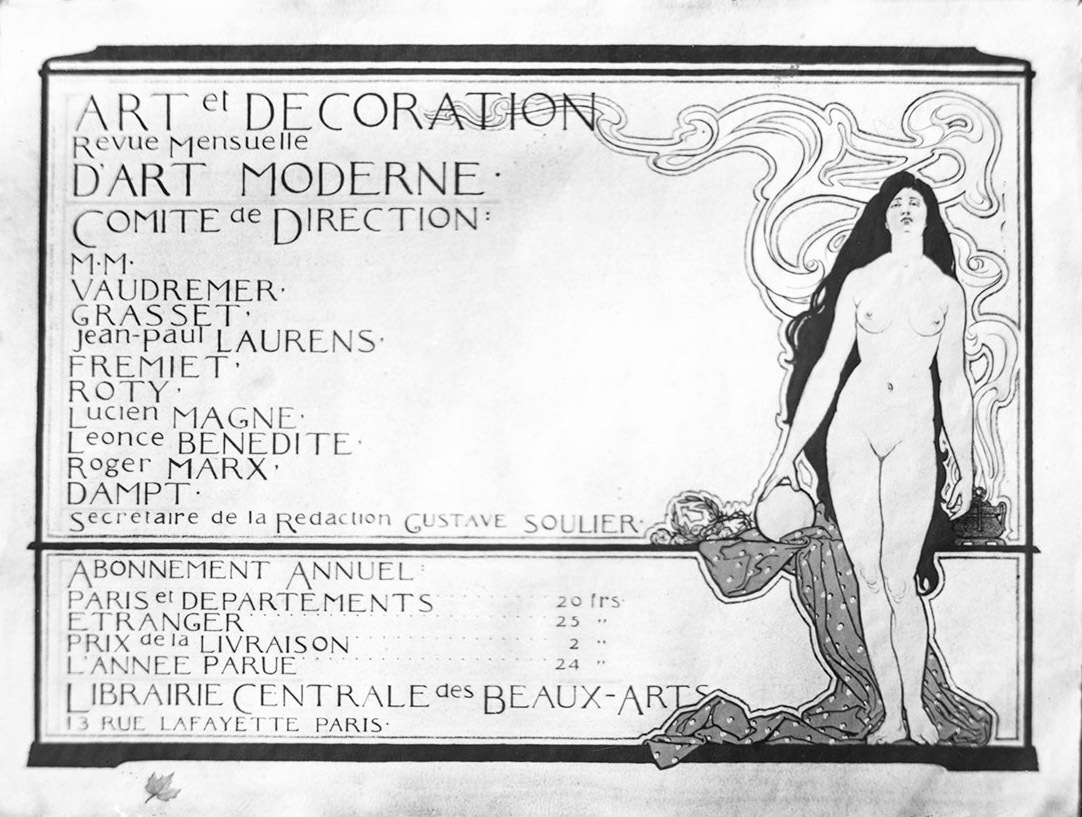

In the absence of first-hand knowledge of contemporary European art, Leduc soaked up as much information as he could through the medium of art periodicals. He subscribed to The Studio, a magazine founded in London in 1893, which provided extensive coverage of current artistic production in England and on the continent. Its graphic style at this time owed something to the influence of the Arts and Crafts movement and also to Art Nouveau. Leduc’s understanding of both Symbolism and Art Nouveau was primarily book knowledge, even though he spent several months in France in 1897. He was interested in the history of symbols, of which there exists a rich tradition, particularly relating to the meanings of plants, colours, and numbers. He went on to study contemporary art movements in France, adopting some of their expressions. His treatment of the subjects he chose was based on his own interpretation of these artistic movements.

Whether in his studies of the human body or his investigations of landscape, Leduc rendered his subjects with intensity and concentration. The forms and variety of his natural surroundings provided him with a constantly renewed source of subjects, as demonstrated by the series of landscapes he painted in the 1910s, or the sequence of drawings he titled Imaginations, 1936–42. He sought to capture the luminous effects of sunset, when the colours are less bright, more nuanced, and the light is viewed obliquely or indirectly, as in Green Apples (Pommes vertes), 1914–15. These works—for example, Erato (Muse in the Forest) (Érato [Muse dans la forêt]), c.1906, or Grey Effect (Snow) (Effet gris [neige]), 1914—evoke a sense of calm and serenity inspired by the day that is ending, when the body rests and the mind gives itself up to reverie.

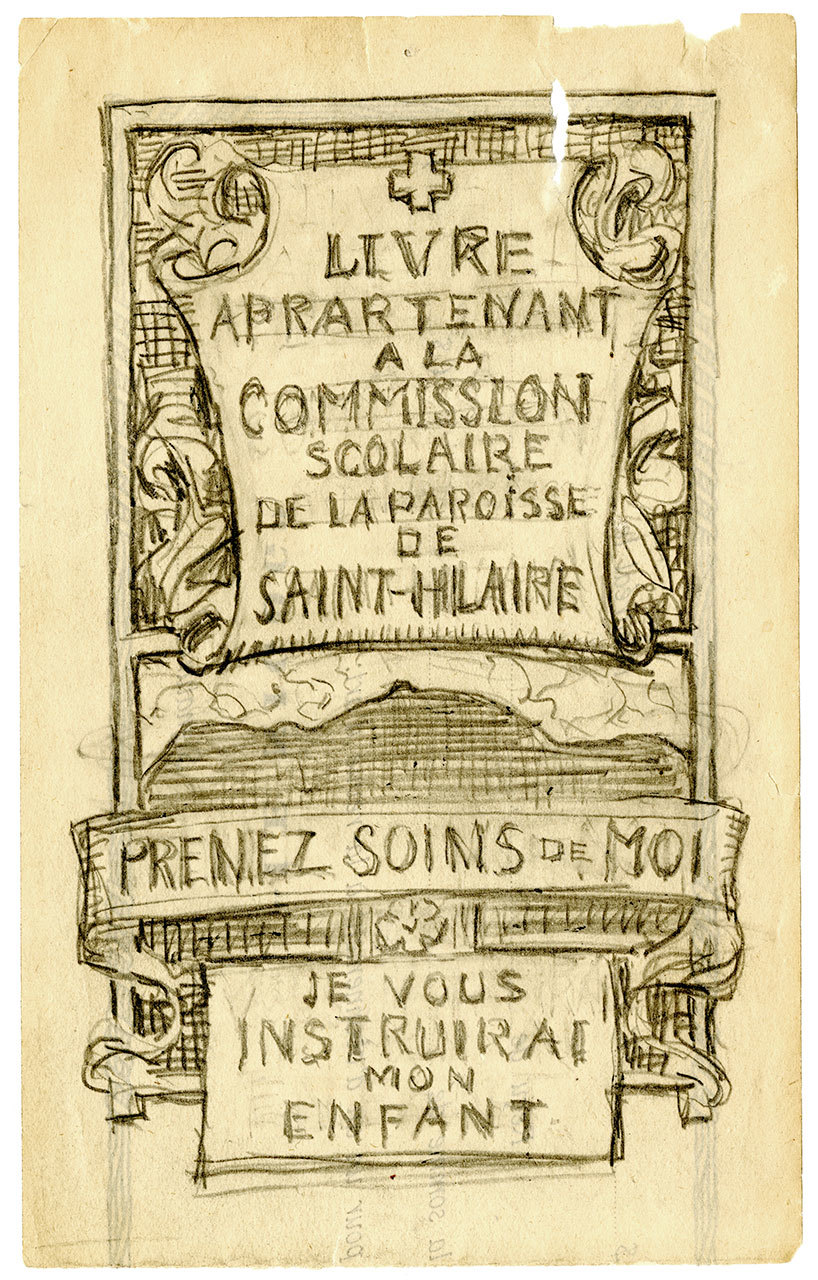

Around 1918–21, Leduc was working on an ex-libris (or bookplate) project for the Saint-Hilaire school board, and the design he created is an indication of his profound attachment to nature. Landscape and books were both sources of instruction, and the painter’s message asked for them to be protected so that their secrets could be delivered. The words Take care of me. I will teach you, my child come as much from the mountain as from the book. The lesson was that the quest was thrilling and demanding, and that it would involve sacrifice and self-denial. Guy Delahaye (1888–1969), Leduc’s poet friend who had shared his exploration of the mountain, dedicated a cycle of poems in his collection Les Phases (1910) to Leduc. The poems evoke the remembered euphoria and danger of those investigations of the mountain’s unique places: caves, escarpment, a lake, and quarries.

The mountain is revealed as a rich repository of emotion and knowledge. Over its slow evolution nature accumulates an infinity of details capable of nourishing the imagination of the artist and at the same time making him aware of his limits, faced with the resources the mountain contains. Its vertical landscape matches the flattened compositions of the artist, who never forgets the two-dimensional nature of the painted surface. In his relationship with the natural world, to which he lends a spiritual dimension, Leduc shows himself to be a profound and natural Symbolist. Like the poet Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), who in his poem “Correspondances” (1857) idealizes the interrelations of “Perfumes, colours, and sounds,” Leduc is sensitive to the “forests of symbols” constituting the universe whose “dark and profound unity” he too wishes to suggest.

Grey Effect (Snow) is constructed of muted tones of grey accented with touches of green, yellow, and blue, recalling the work of the Anglo-American painter James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), especially his Nocturne in Blue and Silver, c.1871–72, with its harmony of colours. Leduc conveys the heavy atmosphere of a winter day when the sky is overcast and the conifers are weighed down by wet snow. In a sense the picture has no subject, yet its purely pictorial effects draw on the vocabulary of Symbolism to show an intimate relationship with nature, bringing out its most secret aspects. The composition makes use of a circular movement. A slight drop of the landscape on the right creates a double movement, rounded and curved, which suggests a relief but without distracting from the sense of confinement evoked by the painting. It is a celebration of a non-event, yet the work is in no way anecdotal; this is a day without effect, except perhaps the weariness that such a dull day brings. Everything is concentrated in the colour and its application in small separate touches whose materiality captures a heavy light.

Technical Means

Leduc’s manner of working evolved slowly over the seventy years of his career. It was always marked by patient application and attention to detail. His student Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960) said of him: “I see him . . . twenty-five feet up in the vault of a chapel, using the point of a pencil to plug the tiny holes left in the plaster where stencils had been pinned; completing the smallest of pictures, for years, with a quiet laboriousness.”

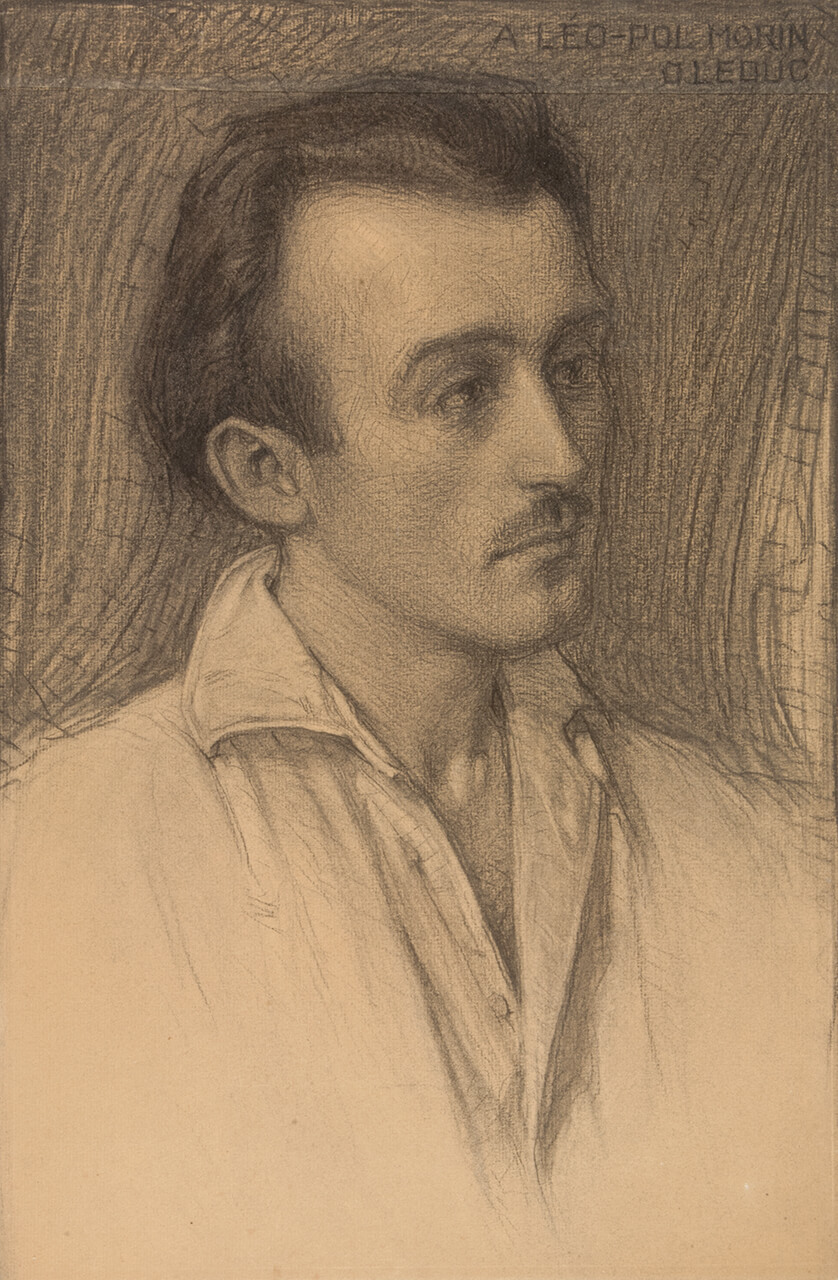

This “quiet laboriousness” defines the patient and rigorous way in which Leduc approached a work of art. Throughout his life he used drawing as a method of forming his ideas. His touch is not rapid in the manner of Matisse (1869–1954) or Picasso (1881–1973), who were able to capture their vision in a single continuous line. Leduc’s drawing is built up with short, successive, superimposed strokes that impart life and density to contours, isolating light and shapes. An eraser underlines the effects of light and increases the relief of the forms, as in Cloud on a Mountainside (Nuage à flanc de montagne), 1922. An economical man, Leduc drew on any and all bits of paper he could find, recycling printed materials or the backs of envelopes to seize transitory ideas, which he would then transpose to a better quality of support when he made his more thorough studies in preparation for a definitive and final work. Every picture went through several first attempts, in which he tried to clarify the composition before painting.

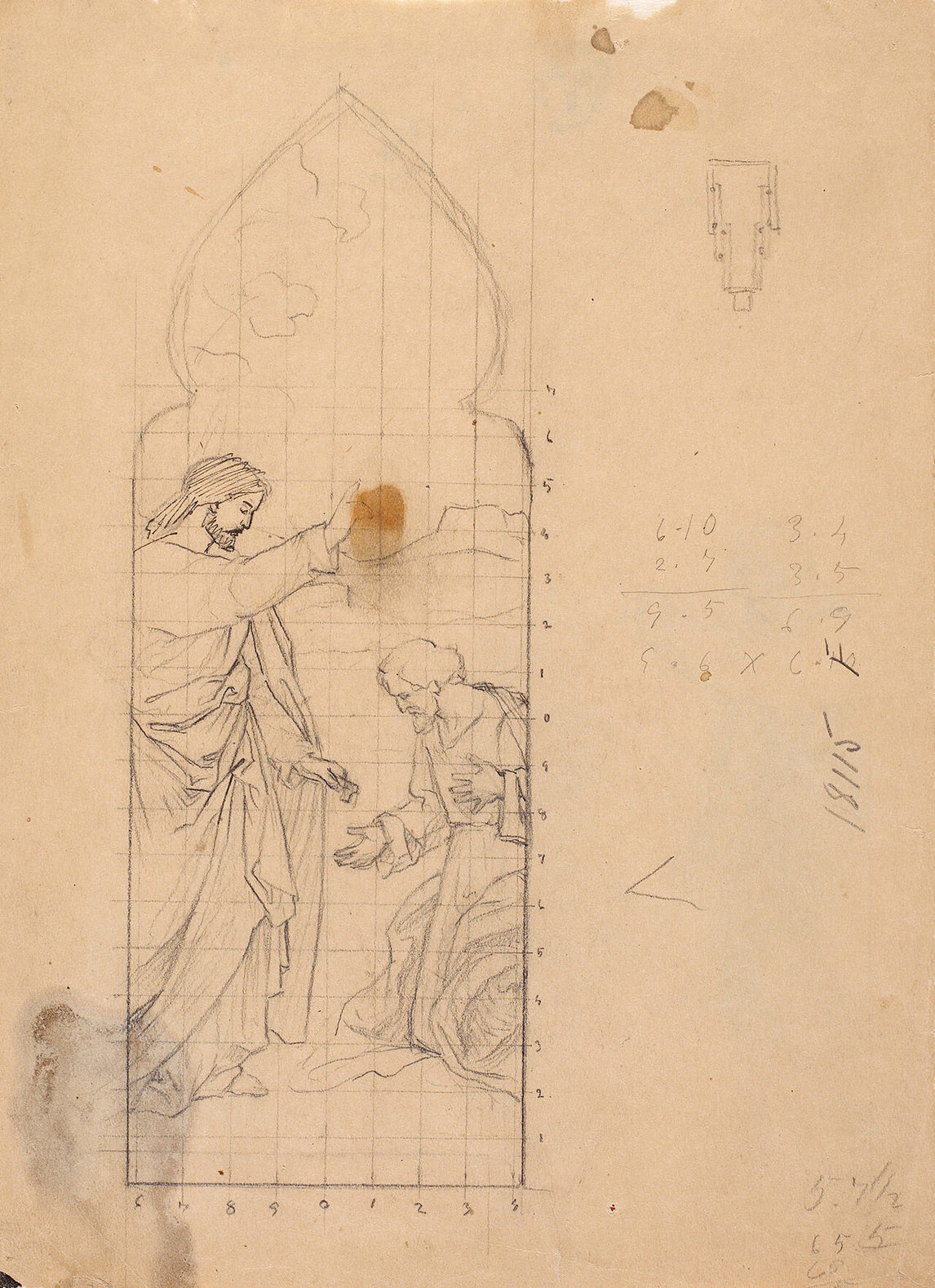

For the large-format religious paintings, Leduc made detailed studies, which he would then grid for transfer. This method enabled him to take what he had envisaged in a small-scale format and transpose it into a much larger one. This process can be seen in his study for Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter (Le Christ remettant les clés à saint Pierre), c.1898–99, or for Mary Hailed as Co-Redeemer (L’Annonce de Maire co-rédemptrice), 1922–32.

Leduc’s studio was too small a space for his huge church-painting projects, so he painted on long bands of canvas that he rolled up as the work progressed. He would then unroll the canvases to check that the colour palette and design were uniform through all the sections, which had sometimes been painted at intervals of months. The sections would be arranged side by side in place to make up the final composition before the whole work was mounted on the walls of the church, as seen in the Church of Notre-Dame-de-la-Présentation at Shawinigan. And always, the work would be adapted to the place, not only in the choice of iconography but also in the composition, taking into account the position of the spectator and the mixing of the colours in the ambient light of the space.

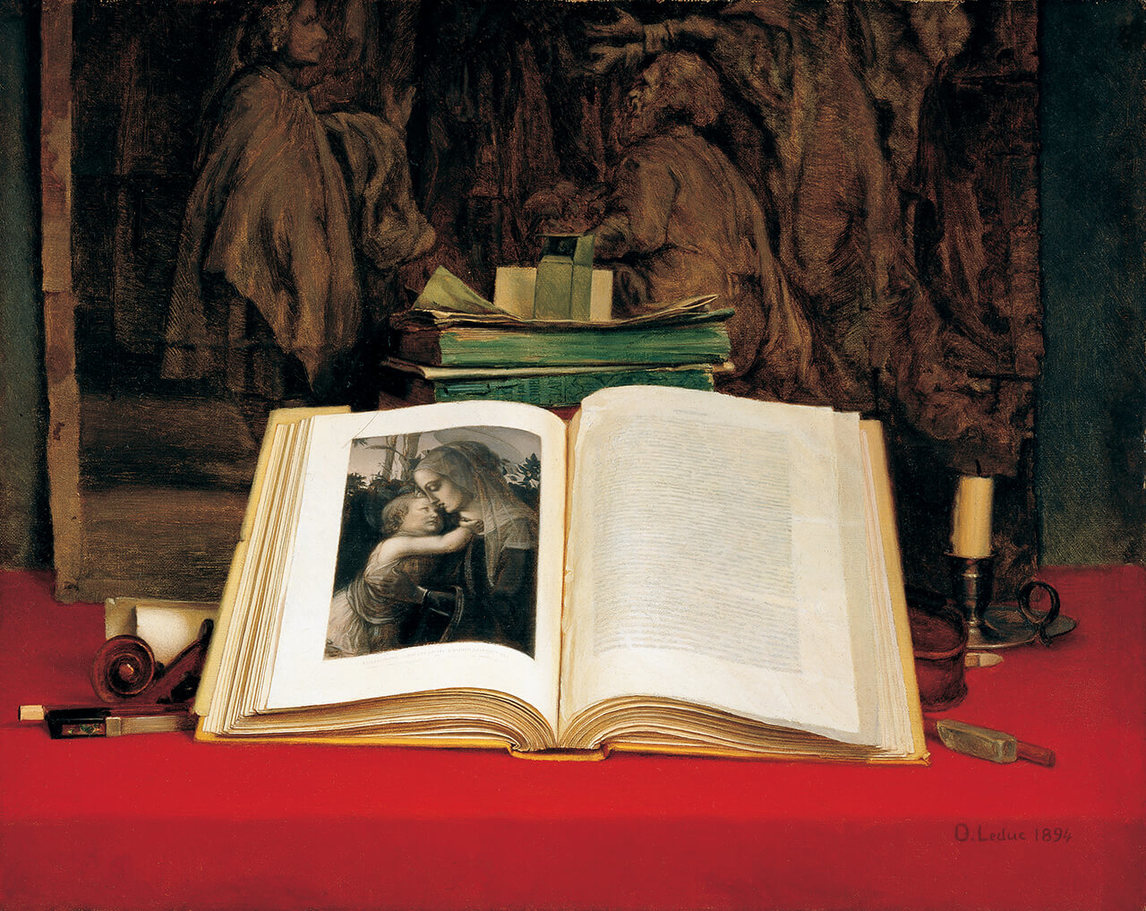

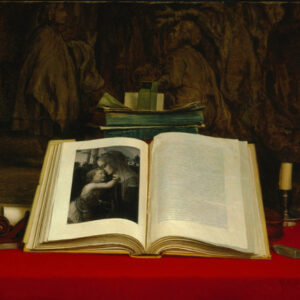

“Drawing, colour, composition,” Leduc wrote around the edge of the Still Life with Lay Figure (Nature morte dite “au mannequin”), 1898. At the beginning of his career Leduc’s method was to make the brushwork invisible, applying colour in thin washes, creating the trompe l’oeil effect seen in Phrenology (La phrénologie), 1892. Critics were appreciative of his technique. For example, in Still Life, Onions (Nature morte, oignons), 1892, Leduc presents this simple vegetable from different angles and with multiple visual effects. Whether they are whole, sprouting, cut in half, or reflected, this inventory of their natural forms insists on the diversity of their overlapping shapes, and confers on them a multiplicity of meanings. With these still lifes, the seductive finish of the canvas and the subdued light draw our attention to the detailed rendering of the materials. Leduc offers a reflection on the complexity of art that combines both skill and understanding, study and imagination.

After 1900 Leduc used a palette knife to visibly inscribe the gesture and the pictorial matter on the canvas, as in Portrait of the Honourable Louis-Philippe Brodeur (Portrait de l’honorable Louis-Philippe Brodeur), 1901–4. These were the two means of signalling the work of the painter: one the technique that rendered the work invisible and invited the viewer to confuse the image with reality, and the other that showed the gestural trace of the paint as it had been applied. In his compositions Leduc emphasized the role played by the surface of the canvas. He generally circumscribed and isolated the subject, sometimes by placing it against a background marked by vibrations of light in an indeterminate space, or in other cases, notably in Mary Hailed as Co-Redeemer, 1922–32, by the way the lines appear to move and mould themselves around the principal subject. Depth is treated by foreshortening, and an emphasis is placed on the application of the pictorial material. In this way, Leduc affirms the signs of his art and invites us to see not only the subject but also the way the subject is presented by means of the characteristics of the paint or of the drawing.

Leduc did a great deal of research and made multiple studies and preparatory drawings for his projects. He devoted much time to this practice. For him, these preliminary steps, in which he worked out his thinking and clarified the conception of the work, could never be carried too far; he would make his sponsors wait—whether members of the clergy who would have to celebrate services in a church covered with scaffolding, or a client waiting impatiently for his portrait. With his easel painting he felt free to take as long as he liked. As he wrote in a letter to the architect Louis-N. Audet, the lifespan of an artwork is recognized in posterity, and the time it takes to complete it is secondary to the years it will survive and be appreciated. “Don’t be alarmed, because a work of visual art is not dependent on time, except in one sense. When you see the completed decoration you will forget the time that was spent on the work.” He was right. We still appreciate his paintings and drawings more than a century after they were produced, and their meanings grow and deepen in the perennial gazes that continue to be cast upon them.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements