Oviloo Tunnillie (1949–2014) began her carving career in 1972. Although few of her works from the 1970s are documented, they were naturalistic depictions of wildlife, particularly birds and dogs, completed with an axe and file. In 1988 she began carving with electric tools, creating detailed scenes that drew from her own life as well as subjects seen on television. Often featuring strongly rendered female figures, her sculptures confront the nature of her materials, embrace the possibility of abstraction, and demonstrate the capacity of stone carving to capture feelings of separation, loss, personal struggle, and the joys of life.

Tools

Oviloo Tunnillie, Owl, 1974, serpentinite (Tatsiituq), 18.4 x 6.1 x 5.7 cm, unsigned, Winnipeg Art Gallery.

Oviloo Tunnillie’s earliest carving is Mother and Child, created in 1966. The serpentinite stone came from a large deposit located near her family’s camp at Kangia on south Baffin Island. Oviloo noted that this first work, as well as her carvings from the early 1970s, was made with an axe and file, the tools of her carver father, Toonoo (1920–1969).1 For an Owl carved in 1974, she remembered using an axe on the body and sandpaper to shape the feathers on the wings.2 As an inexperienced carver who had been selling her carvings sporadically for only two years, Oviloo would have manipulated these hand tools with much physical strength and patience. Dogs Fighting, c.1975, shows how quickly Oviloo’s skill progressed—where Owl is quite blocky, the later work is intricate, and the form conveys the movement of dogs’ bodies.

By the early 1980s some other Inuit carvers used electric tools that enabled them to create sculptures with less effort.3 As explained by Ohito Ashoona (b.1952), “We use power tools so we won’t damage our arms. With hand tools, you see dents because the stone is cracked or chipped. With power tools, the work can be very smooth and polished. I can still carve using hand tools, but the power tools seem better.”4 While Oviloo embraced this new way of working a few years later, others including master carver Osuitok Ipeelee (1923–2005) continued to use tools such as an axe, saw, and files.5

The process of creating a carving, from the carver’s initial rough shaping of the stone to the final stages of finishing and polishing the piece, involves a series of mechanical and artistic choices. An artist must develop not only the physical ability to manipulate the tools needed to work in stone but also a nuanced understanding of what each tool can do.

Oviloo Tunnillie, Self-Portrait with Carving Stone, 1998, serpentinite (Kangiqsuqutaq/Korok Inlet), 53.0 x 37.5 x 33.3 cm, signed with syllabics, collection of Fred and Mary Widding.

In an interview in 1998 with curators Susan Gustavison and Pamela Brooks, Oviloo explained how she created her carvings and the roles played by different tools at different stages of the process:

[I used to use] an axe and a file . . . but ever since I had the operation on my arm, I have been using grinders or electric tools. . . . At first I use an electric chisel. After I’ve used the electric chisel, I use the grinder . . . [then] I use a Dremel [electric drill] to do the finishing. After I am done with all those things, I start using a file, and also I start working with a chisel. After I’ve done with the filing and the chisel, I start sanding.

I have to use four different grits of sandpaper. I start from the roughest to the smoothest. . . . Because the electric tools which I use aren’t meant for small pieces, they are heavy. My arm does get tired when I’m using those electric tools. . . . I used to use wax on a few carvings but there’s fine grit [sandpaper] such as 1500. Although there’s 1500, I would like to get to 2000 grit. Because it would [make the surface] even shinier.6

Oviloo used the different tools at her disposal to create variations in form and texture in her work, from the textured hair of Tired Woman, 2008, to the realistic feathers of her bird carvings from the 1980s. She depicted her own carving process in works such as Self-Portrait with Carving Stone, 1998, which shows the artist holding a piece of stone that is waiting to be carved. She had become so confident in her technical abilities that her artistry and command over the stone resulted in work that made use of notably simpler forms. Nonetheless, they are able to communicate the universal within the particular and reveal hidden meaning.

Materials

Oviloo Tunnillie and other Cape Dorset (“Kinngait” in Inuktitut) carvers have most regularly chosen serpentinite for their carvings. Often, the carving stone used by Inuit artists is described as “soapstone,” but soapstone, more accurately identified as steatite, contains a high proportion of the mineral talc, making it very soft. Many artists find steatite too soft for carving. Serpentinite is a harder rock consisting of serpentine-group minerals that are commonly green, greenish yellow, or greenish grey and veined or spotted with red, green, and white.7

Iyola Tunnillie, Oviloo’s husband, mined Oviloo’s serpentinite stone from a number of sites, including Kangia; Itilliaqjuq (also spelled Itidliajuk), located one mile from Igalalik; Kangiqsuqutaq at Korok Inlet; Tatsiituq, which was also the site of a camp; Kadlusivik; and Aqiatulaulavik, the location of an early camp.8 The carving stone was distinct in each of these deposits, and Iyola is able to distinguish each by examining photographs of the sculptures. Most of these sites were eventually depleted, and the stone used today usually comes from a large quarry at Korok Inlet. Knowledge of stone types is often useful in identifying and dating south Baffin Island carvings.

In addition to serpentinite, another very different material is used in several sculptures by Oviloo. An artist (it is not known who) visiting Cape Dorset stimulated her interest in working with crystals, and she began to use them in her work.9 Beautiful Woman, 1993, for example, depicts a young woman seated, Buddha-like, with a high-heeled shoe peeking out from under the edge of her full skirt. She holds a large quartz crystal in her hand like a sceptre and wears a tiara studded with more crystals inserted like diamonds.

Iyola noted that Oviloo would find crystals in a creek near their house in Cape Dorset: “Right after the snow had melted we would see all these little pebbles.”10 The larger crystals were chipped out of stone found in the lower pit of Kangiqsuqutaq mine at Korok Inlet. Another sculpture with prominent quartz crystals is Sea Spirit, 1993, in which one large crystal adorns the forehead of the sea spirit and her hands hold two others.11

Gallerist Robert Kardosh has commented that, rather than releasing a form contained in a piece of stone, Oviloo relied on her materials as constraints that helped her work through her ideas. Oviloo commented, on several occasions, about the challenge of conceptualizing her sculptures:

It can be very difficult to sculpt the idea that you have in your mind. If your idea doesn’t match the shape of the stone your idea may have to change because you have to accept what is available in the rock.12

Carving involves mental as well as physical effort, and the two are combined in the execution of the work. Oviloo spoke about this in an interview in 1998 when asked about her Woman Thinking, 1996:

In that piece . . . I have come to the point where I don’t know what to make. It has taken me at least three days, on a few occasions, to figure out what I’m going to make. After I have imagined what I’m going to be working on, I start working on the stone. I don’t draw on paper what I’m going to be making. Only after I know what to make, do I start working on the soapstone.13

Several of Oviloo’s most emotive sculptures express the mental strain of carving through the body language of her figures. In Woman Thinking, 1996, Oviloo is seated with clasped hands pressed to her bowed head. Her raw material is the subject of the artist’s deep contemplation in Woman Carving Stone, 2008. Her upper body and head are bent over a large piece of stone, expressing fatigue and the immense physical effort she will need to carve it.

Realism and Autobiography

Realism in Oviloo Tunnillie’s work is present not only in the form and details of her subjects but also in the attitude her work takes vis-à-vis both the artist’s past and her everyday life. She was one of very few Inuit carvers to extend her approach to realism into detailed autobiography. A work from 1991–92, This Has Touched My Life, is a realistic depiction of a memory from her years in southern sanatoriums and was among the first of many autobiographical pieces. The humorous work Nature’s Call, 2002, is an example of Oviloo’s unhesitant and forthright depiction of the human body and bodily functions.

In the 1970s and 1980s Oviloo created elegantly naturalistic animal compositions, particularly of dogs and birds, depicting them with great attention to naturalistic detail. In Dogs Fighting, c.1975, several animals interact and form a complex composition that expresses their frenzied movement. Oviloo also carved realistic birds in her earlier years. These were usually hawks, as in Hawk Landed, c.1989, and Hawk Taking Off, c.1987. In the former piece, Oviloo’s appreciation for the qualities of the stone is apparent. Details such as feather patterning and claws are carefully defined. In an interview in 1991 she explained her enjoyment of carving birds:

With my carvings right now the bird is my favourite subject to carve. The things that are simple in detail. . . . Right now, I like carving birds with wings spread out. I like to carve the stone very thin on the wings. When I do this, a lot of the stone comes off because I try to take the bulk of the weight off. . . . I try to carve a bird that has a flow to it. . . . I find a great joy when the stone starts to take a shape.14

While there are many Cape Dorset sculptors whose works are famous for their detailed depictions of Arctic wildlife, Oviloo’s degree of precision can best be compared with the art of Kananginak Pootoogook (1935–2010), who has been described as the “Audubon of the Arctic.” For Oviloo’s two hawks from c.1987 and c.1989, it is possible to distinguish their specific species—the rough-legged hawk.

In another work, Dog Chasing Bear, 1977, the determined pursuit of the dog and the bear’s panicked attempt to escape are palpable. Here, the attention to realism is in the context the scene alludes to as well as in the details of its subject. Dogs were an important source of protection for people in camps on the land. A pack of dogs could also circle and trap a polar bear, making it vulnerable to the spear or rifle of a hunter. In keeping with Oviloo’s later approach to scenes from her own life, in this piece she uses a key moment to suggest a much larger narrative.

In 1997 Oviloo gave a succinct summary of her art and her subjects: “They are personal experiences that I’ve had and that’s why I like creating them. My carvings are what I’ve seen, what I’ve experienced.”15 On another occasion she noted, “Some people write about their lives but I carve about my life. That is the way I want to be known.”16

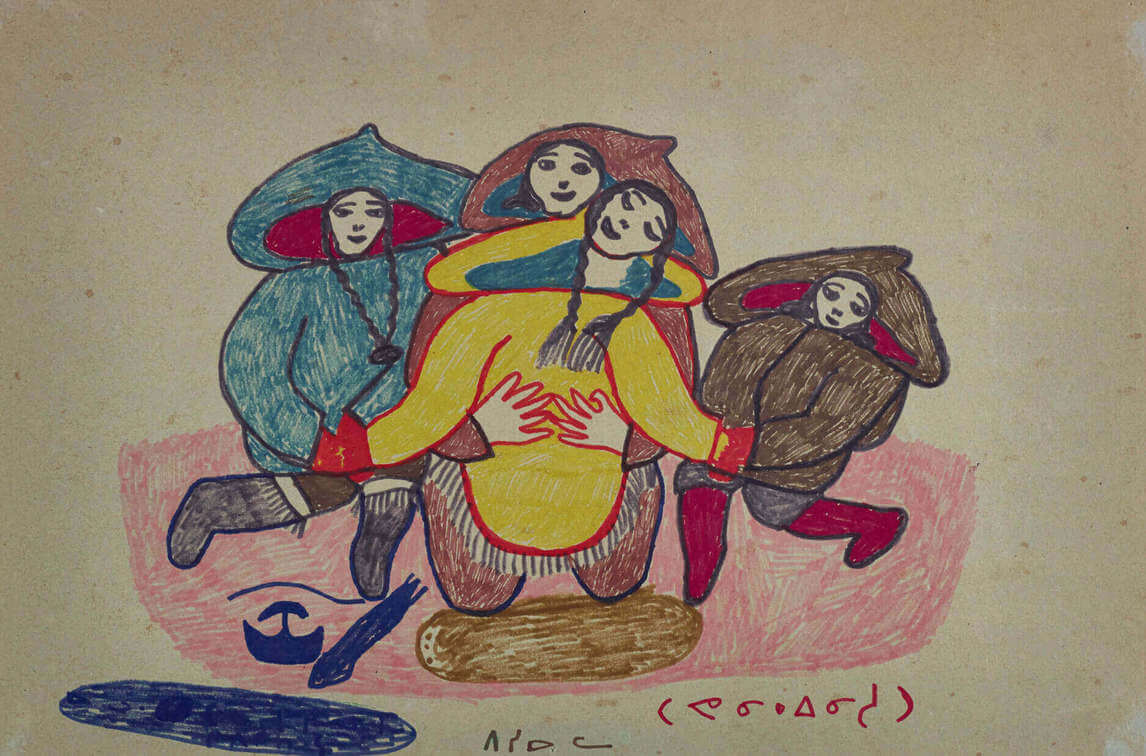

By the 1990s, when autobiography had become a defining factor in Oviloo’s art, she included a degree of narrative, particularly for her “hospital” works. At the time Oviloo was carving, only a few Inuit artists included autobiography in their work. Graphic artist Pitseolak Ashoona (1904–1983) and her daughter Napachie Pootoogook (1938–2002), for example, show women in a social context in which they are defined by the roles of wife and mother. However, over the course of her career, Oviloo’s sculptures became increasingly less narrative, focusing on an individual subject without necessarily suggesting a larger context or story, as in Self-Portrait with Carving Stone, 1998.

Oviloo’s autobiographical carvings are usually single figures that carry the meaning of her memories and self-reflections. The delightful Self-Portrait on a Sled in 1959, 1998, was a memory from 1959: “That’s the first time I started sliding. Using a sled like that.”17 A later memory, Self-Portrait (Arriving in Toronto), 2002, shows Oviloo with a suitcase as she arrives at the Toronto airport in 2000 or 2001. Her short-sleeved dress reflects her landing in a new, southern culture, but there are no elements to suggest what she is doing there or how long she might stay. It seems to indicate her initial excitement and anticipation of an urban lifestyle that was a dramatic contrast to life in Cape Dorset. As is often the case, Oviloo expresses a state of mind through clothing and hair.

Abstraction—The Robed Figures

From the 1990s on, Oviloo Tunnillie created a series of solitary female figures clothed in robelike garments that drape and flow over curvaceous bodies, as well as sculptures that show nude female subjects. With these figures, the artist often eschews the detail that can be seen in her realistic works and imbues the sculptures with an abstracted emotion. Culturally unspecific, the clothing does not detract from the expressive body language of the figures. Hair also contributes to the strong general impression of sensuous femininity. It is usually long and flowing, as in Woman with Long Hair, c.1994, and is often the only part of a sculpture with textured surface detailing. Just as the short, bobbed haircut and bangs represent Oviloo’s hospital years, as seen in Nurse with Crying Child, 2001, so the cascade of beautiful hair is expressive of mature womanhood.

Robert Kardosh, director of Marion Scott Gallery, Vancouver, has aptly described Oviloo’s sculptures as “emotional portraits” that express psychology over narration.18 Oviloo’s later self-portraits, such as Woman Thinking, 2002, are defined by what they feel, not by the role the figure plays in society. In fact, for works such as Repentance, 2001, or Woman with Pot, 2001, viewers may wonder if they are seeing work by an Inuit artist, as Oviloo’s sculpture crosses cultural lines. Her smooth, undulating forms in the polished stone often come close to abstraction. There is very little detailing apart from the powerful language of the human body.

In these figures, the facial expression is not important and is often covered by hands that reveal sorrow or contemplation. In Diving Sedna, 1994, for example, the figure’s face is hidden, giving prominence to the rest of the body, while in Crying Woman, 2000, a nude figure cradles her head in her arms, which rest on her drawn-up knees, curling into herself mentally and physically. It is an image of complete introspection and vulnerability.

As indicated by the title of the last Marion Scott Gallery exhibition of Oviloo’s work in 2008, Transcending the Particular, her sculpture eventually moved away from the details of southern culture that intrigued her earlier, such as the party dress of Beautiful Woman, 1993, and subjects from popular culture that she viewed on television, such as Football Player, 1981. Oviloo’s generalized female subjects, such as Grieving Woman, 1997, exude the emotions of the human condition that transcend gender and culture. Few carvers have been able to accomplish the abstraction of pure emotion through cold, hard stone.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements