Oviloo Tunnillie (1949–2014) was an internationally respected Inuit artist from the territory of Nunavut in the Canadian Arctic. In the south Baffin Island hamlet of Cape Dorset (“Kinngait” in Inuktitut), where Oviloo established her life as a sculptor, carvers were typically men, whereas women artists created drawings, prints, and textiles. Defying convention, Oviloo forged an iconic career as a stone carver. Her work challenged Inuit stereotypes, daringly exploring a wide array of subjects, including alienation, alcoholism, animal abuse, and grief. In 1966 she sold her first piece. She carved continually from 1972 to 2012, when she stopped after being diagnosed with cancer a second time. The disease claimed her life in 2014.

Early Years

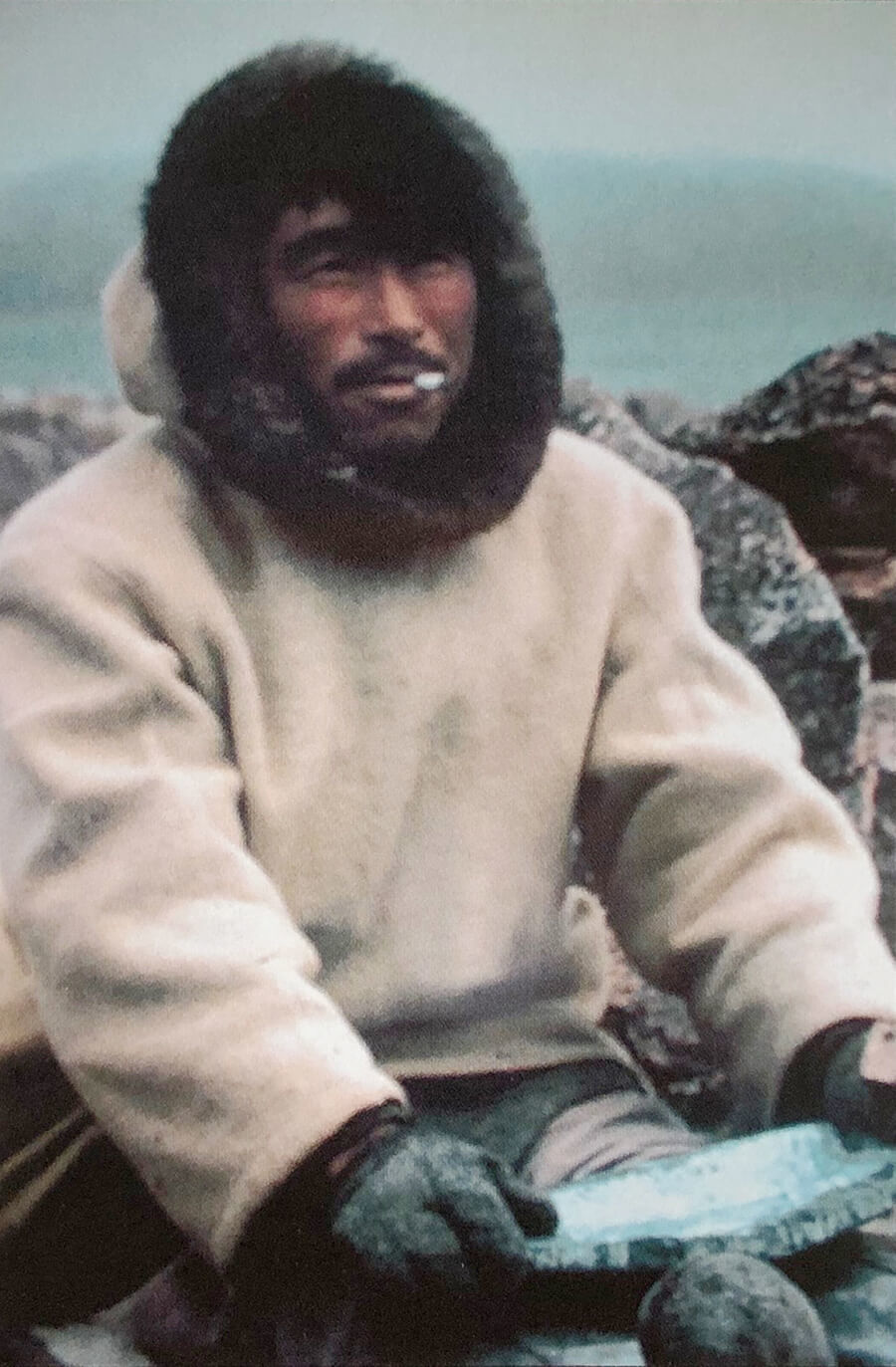

Oviloo Tunnillie was born in 1949 in Kangia, one of several small camps situated along the coast of south Baffin Island. She was the second child born to her mother, Sheokjuke (1928–2012), and her father, Toonoo (1920–1969).

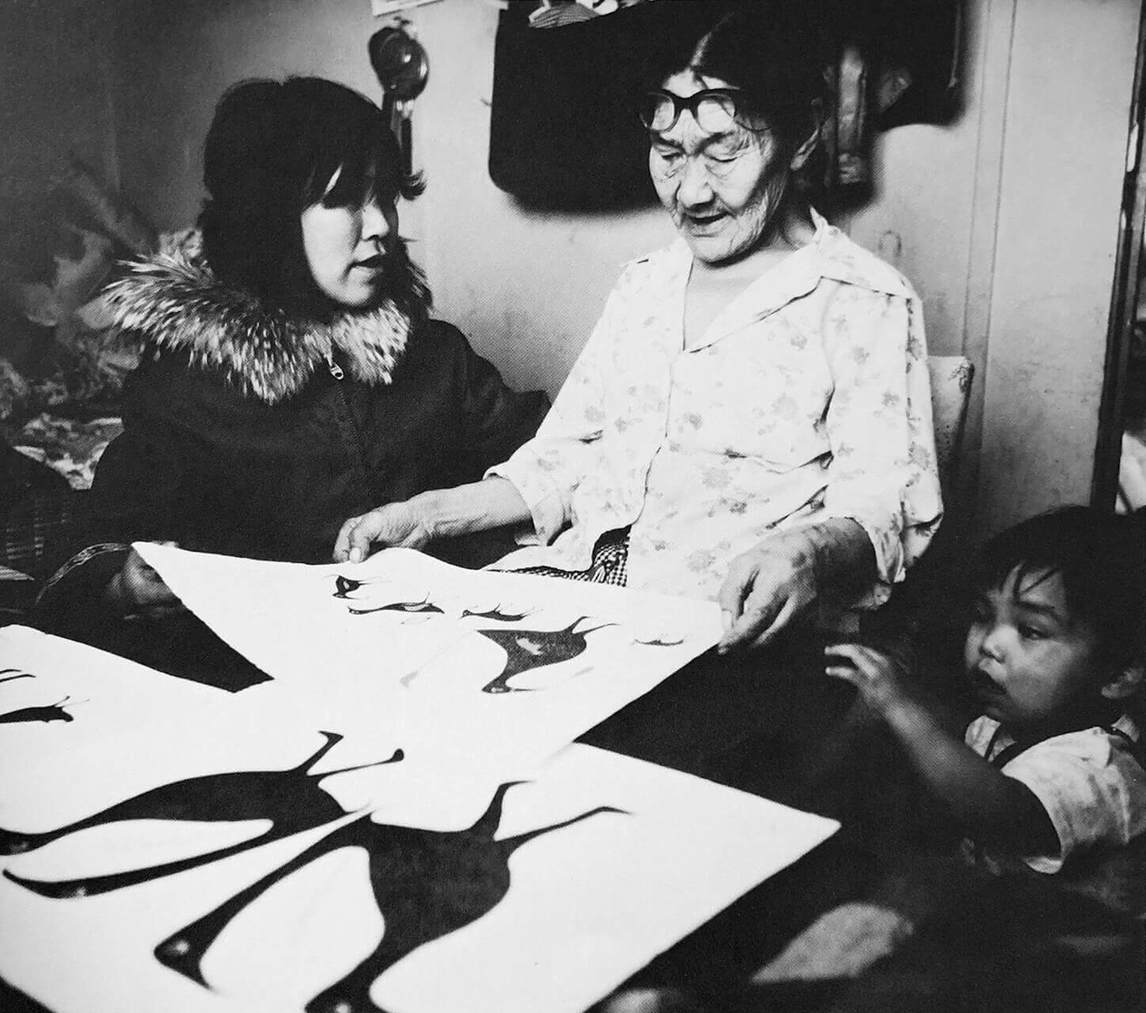

Oviloo’s parents had been married in the early 1940s, when Sheokjuke was in her teens. Sheokjuke’s mother, Mary Qayuaryuk (1908–1982), also known as Kudjuakjuk, was a respected graphic artist who created drawings and occasionally carvings from the late 1950s until her death. She was first married to a man named Pitseolak, who died young of fever, and later married a carver, Kopapik “A” (1923–1969). Toonoo had been one of five children—including Ohito (m), Napatchie (f), Koperqualuk (m), and Pilitsi (m)—most of whom died young and were childless.

Oviloo’s older sister, Nuvalinga, was born in 1946. Several other children followed Oviloo: Timoon (b.1955), Jutai (1959–2015), Laimiki (b.1962), Iqaluk (b.1966), and Samonie (Sam) (1969–2017). Three children who were also adopted into the family: Tuqiqi (b.1964), Eegyvudluk (b.1947), and Iyola (n.d.). One of Oviloo’s siblings, Nungusuitok (b.1964), was adopted out to Mary Qayuaryuk.

As a young child, Oviloo lived with her family in Kangia, a settlement of four or five qammait (semi-permanent sod dwellings) inhabited by Toonoo’s extended family of aunts, uncles, and cousins. In an interview, Oviloo’s sister Nuvalinga explained that the family remained in Kangia throughout her and Oviloo’s childhood:

We lived in the qammait. In the late 1950s and very early 1960s, we finally moved out. In the spring or summer we would travel farther south to collect whatever our father was hunting in those areas. Depending on whether it was duck or goose season or caribou season or walrus season, we would move to different areas so my father could hunt. In the winter we would come back to Kangia to live until spring. . . .

In the fall there was a lot of seal-hunting. We would catch harp or bearded seal and would cache our catch in different areas. In the winter when we ran out of meat in our camp, our father would go out and get meat from a cache.

In the 1950s and 1960s Toonoo, a respected carver, sold his work regularly to fur traders in the area. He was one of the first artists from Cape Dorset to achieve individual recognition in the early 1950s. In 1953 his carvings were included in a historic coronation exhibition at Gimpel Fils in London, England. A year later another major exhibition and catalogue, Canadian Eskimo Art, organized by the Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources, included two of his pieces: an endearing Boy Holding Dog and a bold Rock Cod, both dating to 1953–54. Toonoo’s carvings show a sensitive treatment of both stone and subject matter, as in Mother and Child, 1960–65, part of the Winnipeg Art Gallery collection. Carefully smoothed surfaces enhance the introspective demeanour of the woman, who stands quietly while her small child peers inquisitively from the protection of her amautik.

Toonoo’s art fascinated the young Oviloo and would later inspire her own interest in carving. The family’s camp at Kangia was located near the site of attractive serpentinite and marble stone deposits at Andrew Gordon Bay. Toonoo and two other well-known carver residents in Kangia in the 1950s, Tikitu Qinnuayuak (1908–1992) and Niviaqsi (1908–1959), used these materials for their carvings. Still, art was always secondary in Toonoo’s life. Nuvalinga recalled, “He was a carver and a hunter; a hunter more than a carver.”

Childhood Disrupted

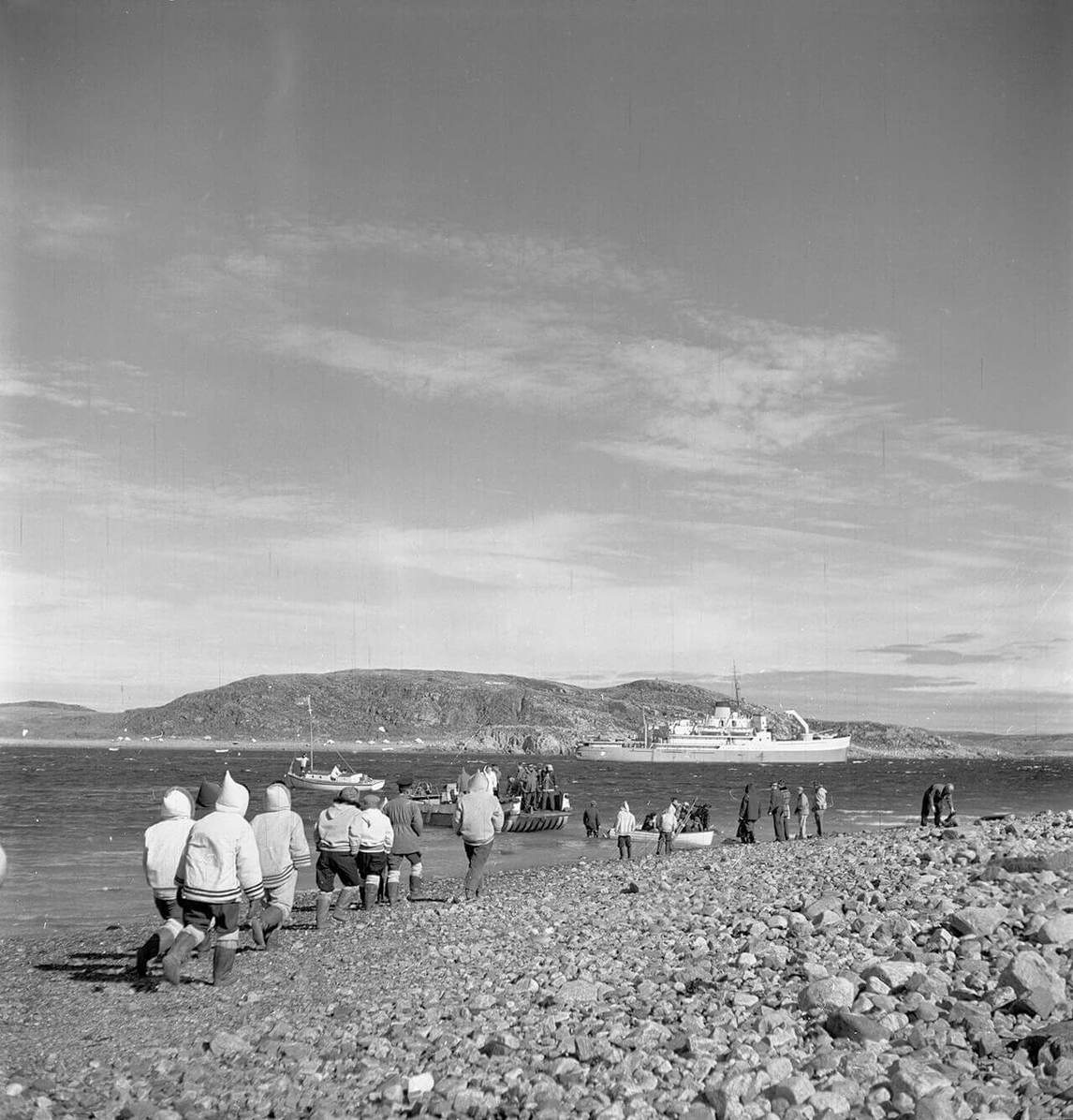

In the spring of 1955, when Oviloo Tunnillie was five years old, her life with her family came to an abrupt end. As a result of European contact and colonization, Indigenous populations had been afflicted by various diseases, including tuberculosis (TB), since the nineteenth century. By the 1950s the disease had infected increasing numbers of Inuit. Rather than build hospitals in the North, the Canadian government chose to forcibly remove Inuit patients to southern sanatoriums. A Canadian government ship called the C.D. Howe arrived at Kangia to screen residents for tuberculosis. After conducting chest X–rays onboard, medical staff told Oviloo and her family that she had the disease and that when the ship left, it would take her to a southern hospital. As Oviloo later recounted:

I remember, there was a ship in the community which did medical checkups. We were picked up by a boat from our tent. That’s the first time I ever started crying. That was the year 1955, when I was five years old. I was told that I had TB, that’s why I had to leave. . . . I don’t even really recall what actually went through my mind, but I know I was really sad because I was leaving my father and my mother and I was going to be alone. I was scared because I was only a little girl.

Oviloo was taken to the Clearwater Lake Indian Hospital in Manitoba, where she lived with other Indigenous tuberculosis patients. In the fall of the following year, she returned to her family at Kangia, but a year later the disease recurred and she was once again taken to the hospital in Manitoba, this time for two years. She said of this second departure:

I was heartbroken to have to leave my mother and father again. My father and I went to ask the nurses and government administrators not to send me away because I did not want to go. But we couldn’t do anything, so I was sent to the hospital again by C.D. Howe, and I spent a lot of time crying under the table. We arrived in Hamilton and I spent a month there, and then I was sent to a hospital in Ninga, Manitoba, near Brandon. At that place, I had an appointment to see two female nurses or doctors to be examined. . . . I was under their care for two years during 1957 and 1958.

Surrounded by hospital staff who did not speak Inuktitut during both of her stays in the South, Oviloo experienced feelings of isolation that marked her memories of that time. Her treatment included periods of bedrest during which medical personnel tied her to her bed. At least one doctor sexually abused her. Oviloo would later reference this difficult time in her life in works such as Nurse with Crying Child, 2001, and Oviloo in Hospital, c.2002. Though the experience of being taken to southern hospitals was not unique to Oviloo, she remains the only Inuit artist to have referenced it directly in her work. Discussing her journey home, she remembered the joy of being back among familiar sights:

Then during the springtime of [1958], I think it was in April, I was sent back home to Cape Dorset by plane. And from there I was taken to my parents’ camp by dog team. They were living at Nuvujuak [Nuvuqjuak] at that time. While we travelled, I remember being so happy to be back home. I collected stones that I liked on the way. I had started collecting them in Ninga, especially the white stones.

Eight years old when she finally returned to her family, Oviloo found the transition back to life in the Arctic challenging. She recalled:

When I think back now, I went through some happy and some unhappy times. After I had returned to my parents’ camp, I had a hard time adjusting because apparently I had adopted too much of the southern culture and I had lost some of my Inuktitut. . . . When someone brought in aged meat and I was offered some, I really thought that they were trying to kill me. I couldn’t communicate with them in Inuktitut, and I did not like the taste! But later on, I realized that this kind of meat was a delicacy. I really craved milk. Since I did not like tea without milk in it, I thought my mother was just being eager for me to cry.

It was like I had just met my family for the first time. I couldn’t understand their ways nor their language because I had gotten so used to the southern ways. . . . The cultures of the Inuit and the qallunaat [non-Inuit] were very different then.

Oviloo gradually adjusted to life at home with her family, which expanded in 1959. Her mother gave birth to a son, Jutai, who later became one of the most original graphic artists and carvers working in Cape Dorset. Oviloo recalled this happy period:

Later on, after we had been back to our camp for a while, my mother gave birth. . . . It was a happy time when she gave birth even though we did not like nurses or doctors being around all the time. Later on, I would go along with my father by dog team. It was fun. Dogs were so useful then, pulling a sled with a number of people on it; they were our only means of travel in those days.

However, that same year life became more difficult when Oviloo’s father, Toonoo, was sent to a hospital in the South for a year. The nature of his illness is unknown, but when he returned in 1960, the family moved from Kangia to Igalaliq, a large settlement near Cape Dorset and located close to deposits of excellent serpentinite stone. Igalaliq was also the main home of respected camp leader, artist, and shaman Kiakshuk (1888–1966), and carvers Kiugak Ashoona (1933–2014) and Qaqaq Ashoona (1928–1996).

Oviloo’s family was part of the first generation of Inuit artists who traded in Cape Dorset in the 1940s and 1950s and sold carvings to the Baffin Trading Company (1939–1946) and the Hudson’s Bay Company. The West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative was established at Cape Dorset in 1961 and became the most important purchaser of arts and craft items. Oviloo noted, “Along with my father, other people were carving at Igalaliq—Niviaqsi and my grandmother, Kudjuakjuk.” A hard, black stone was available near the camp. A couple of kilometres away at Itilliaqjuq (also Itidliajuk) was another stone quarry and camp, where respected carvers Osuitok Ipeelee (1923–2005), his brother Sheokjuk Oqutaq (1920–1982), and Manumi Shaqu (1917–2000) frequently resided. Toonoo used stone from both these sites.

Early Interest in Carving

In Oviloo Tunnillie’s new home in Igalaliq, with her family, her father’s influence inspired her early interest in carving. As she described:

I remember seeing the rocks, different shapes of rocks that I admired. At that time I didn’t know I could carve, but by watching my father, Toonoo, I learned. I loved my father’s carvings. From there I began to learn to carve, always noticing the beauty and shapes of the rock.

Oviloo also noted an early attraction to the stones she encountered on the land:

We would travel by dog team during the month of May, and as soon as I was untied from the sled, I would go to look at rocks and collect them. I have always been fascinated by rocks for as long as I can remember.

However, Oviloo’s interest in carving did not align with the usual social roles in Inuit culture. Nuvalinga remembers that, as the oldest daughter, she was expected to help her mother with the sewing. Oviloo was not interested in sewing and enjoyed spending her time with her father. Nuvalinga recalled:

I always had to help with the sewing. My mother would start the kamiks [skin boots] and would leave the hardest heel part for me to finish. We had to make kamiks two or three times a year for our family. That’s all the women did. We were always cooking or taking care of siblings. Oviloo actually started carving stones at a very young age. She was not too much into sewing like her sister and mother.

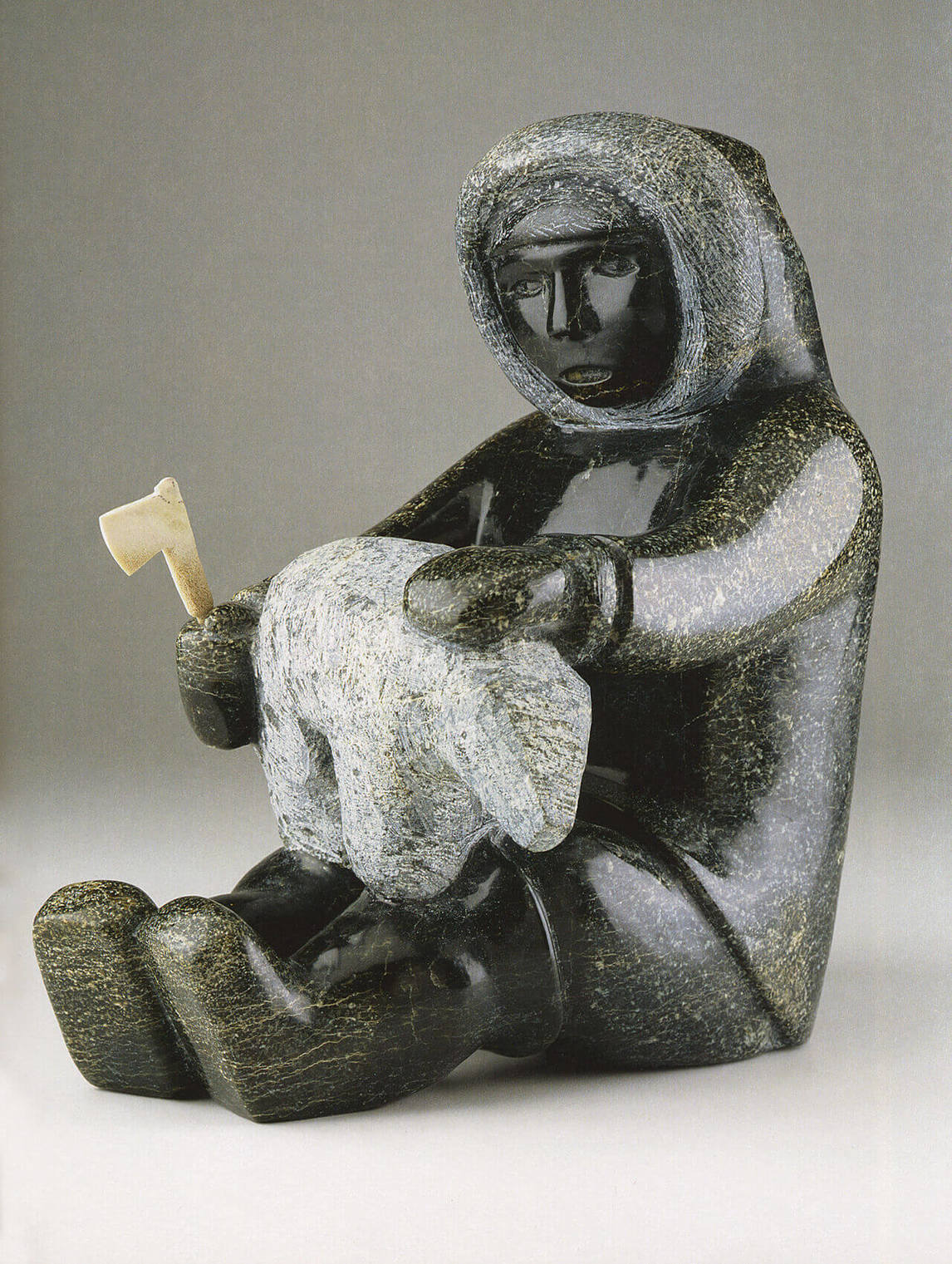

Just as his daughter would in later years, Toonoo enjoyed creating human figures, and a Mother and Child of his from the early 1960s is in the Winnipeg Art Gallery collection. Another piece by Toonoo from the early 1950s, Boy Holding Dog, foreshadows the respect and affection for the animal that Oviloo would depict in her own sculptures—for example, Protecting the Dogs, 2002.

In 1966 Oviloo created a large Mother and Child carving. Although at the time there were a few Inuit women who carved sporadically—Kenojuak Ashevak (1927–2013) and Qaunaq Mikkigak (b.1932), for example—in the camp where Oviloo lived with her family all the carvers were men. This absence of female exemplars did not deter Oviloo. Toonoo took his daughter’s first carving, along with several of his own pieces, to a Hudson’s Bay Company trading post several miles away from where they were living. The carvings were traded for goods available at the post. Oviloo remembered this work in several conversations, including in 1994:

Then in 1966 when I was seventeen, I made my first carving to see if I had a talent for it like my father did, and I was so happy to get things I wanted when I got paid for it. I bought canvas and duffle with the money. I found, too, that I enjoyed making carvings.

Toonoo’s carvings and Oviloo’s 1966 piece all appear to be made from the dark grey serpentinite found near Kangia, and Oviloo would have used her father’s hand tools, an axe and files, to create this work. There is little movement or detailing, and it is more similar to the style of Toonoo’s carvings than to the ones Oviloo would go on to create. But completing and selling this first work proved to be a formative experience. When Oviloo returned to carving in the early 1970s, this early sense of fulfilment propelled by her intense skill would contribute to her confidence that there would be buyers for her art, essential if her work was to gain the respect of her community.

Marriage and Life in Cape Dorset

The late 1960s were marked by tragedy for Oviloo Tunnillie. Her father, Toonoo, was shot to death in 1969 by her sister Nuvalinga’s spouse Mikkigak Kingwatsiak, in what was believed to be a hunting accident. Toonoo was a highly respected member of his community, both for his hunting prowess and his pleasant personality. His death was a great shock, and this trauma would re-emerge twenty-five years later when Mikkigak, believing that he was about to die from an illness, confessed to murdering Toonoo. When Mikkigak unexpectedly recovered, Oviloo’s mother, Sheokjuke, declared that no charges would be laid and that forgiveness would replace punishment. Her decision fits both with her religious beliefs and with the traditional Inuit conception of justice, which does not include imprisonment. The family continues to feel the effects of Toonoo’s death and even today refuses to discuss the details of his murder.

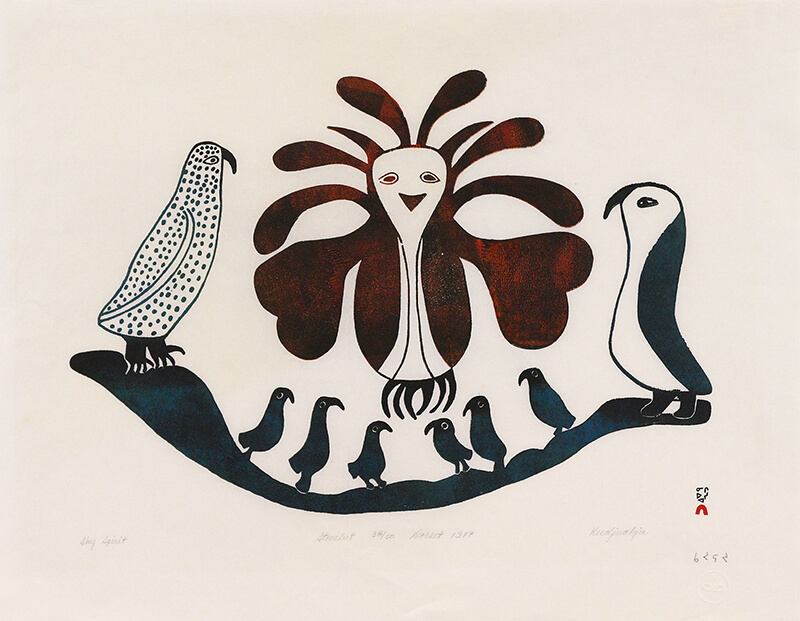

At the time of her father’s death, Oviloo was the oldest of her siblings living with their mother, and with the loss of their family provider, she was married to Iyola Tunnillie (b.1952) in 1969. Iyola was from an artistic family that included his well-known carver father, Qabaroak (Kabubuwa) Tunnillie (1928–1993); his mother, Tayaraq Tunnillie (1934–2015); and his grandmother Ikayukta Tunnillie (1911–1980). Ikayukta had begun drawing around 1963 and created prolifically until her death. Her daughter, Kakulu Sagiatuk (b.1940), is also a prolific graphic artist. Ikayukta was a positive influence on Oviloo, who depicted her in several sculptures, including Ikayukta Tunnillie Carrying Her Drawings to the Co-op, 1997, and Ikayukta Tunnillie Holding Her Drawing of an Owl, c.2008. Oviloo said of Ikayukta:

I really liked my husband’s grandmother. . . . We lived in the same house and I looked after her. It was only when she wasn’t going to live for too much longer she moved out of our house. I think of the advice she used to give me and I can still use the advice today.

Oviloo had moved with her family to Igalaliq, in the Cape Dorset area, in 1959 or 1960. She stated that she spent six months in Cape Dorset in 1970, and sold her second carving at that time. The West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, which did not incorporate until 1961 but had been publishing annual print collections since 1959, provided a way for local artists to guarantee a market for their work. The Co-op’s purchase of carvings and drawings to make prints had increased after the 1965 creation of its central marketing agency, Canadian Arctic Producers, then located in Ottawa.

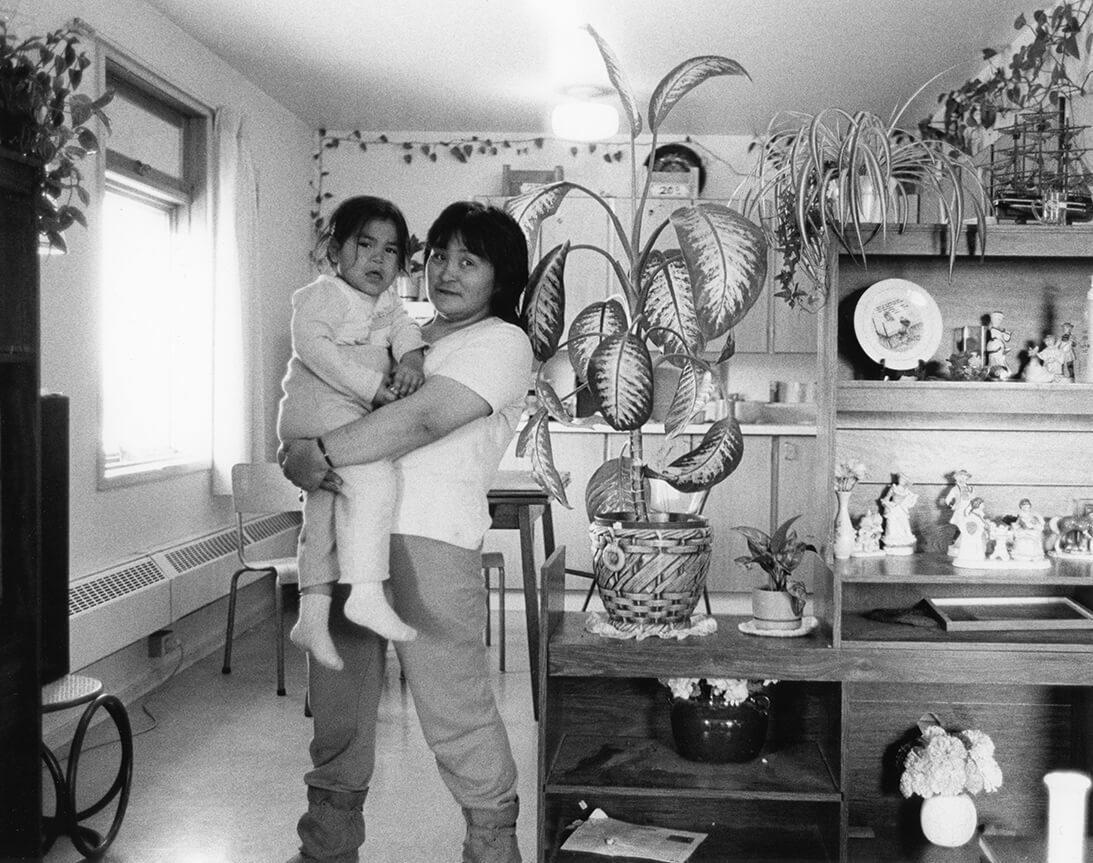

Between 1972 and 1984 Oviloo and Iyola had six children: daughter Alasua (b.1972); daughter Saila (b.1973), who was adopted out; son Tytoosie (b.1974); son Noah (b.1976); son Etidloi (b.1982); and daughter Komajuk (1984–1997). In 1972, after the birth of Alasua, Oviloo and Iyola moved permanently into the community of Cape Dorset.

The family’s settlement was later than that of many other artists who moved into Cape Dorset in the 1960s to find employment or so their children could attend school. As a hunter, Iyola did not need to be in town to support the family. In the early years of their marriage, the couple was able to live on the land, though they were never far from the community. Later in her life, Oviloo would link the beginning of her artistic career to their move into town: “I have been carving ever since my [first] daughter was born in 1972,” she said. She began regularly making carvings because she needed money to buy milk, and her work soon became the family’s primary source of income. Maternal and artistic roles are combined in her large Self-Portrait with Daughter Alasua in 1972, 2000. Here, Oviloo shows herself ready to work on a raw piece of carving stone with an axe.

In the early 1970s Oviloo participated in a West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative jewellery project that began in 1971. It was one of several experimental projects, including film animation, weaving, ceramics, and typographical printing, initiated by the Co-op at that time to develop “Cape Dorset’s creative aspect.” The jewellery program gave employment to both women and men; they learned to use ivory, bone, and stone to fashion necklaces, earrings, buckles, cufflinks, pendants, and pins. Carvers were taught the technique of casting using familiar hand tools and bronze and silver instead of stone.

In 1976 a much-publicized sales exhibition, Debut—Jewellery from Cape Dorset, was organized by the Canadian Guild of Crafts (now La Guilde) in Montreal, and twelve of Oviloo’s pieces were included. A cast bronze Man and Bear, 1974–76, by Oviloo from that show is now in the guild’s permanent collection, but the locations of the other works—which were untitled on the guild’s list for the exhibition—are unknown. The jewellery project was discontinued shortly after the exhibit, as it was not economically feasible for the Co-op, but for about four years it gave Oviloo another source of income in addition to stone carving. It also made it possible for the first of Oviloo’s works to be included in a public exhibition and must have given her encouragement to continue carving to support her growing family.

Establishing a Carving Career

Throughout the 1970s Oviloo Tunnillie worked at home, using hand tools to create realistic subjects, such as Dogs Fighting, c.1975, Dog and Bear, 1977, and more typical depictions of wildlife, particularly birds. She also carved domestic scenes such as Mother Cleaning Child’s Nose, 1977. Intimate subjects such as this were unusual for a Cape Dorset carver, probably because most carvers were male. They were much more usual in communities with a high number of female carvers, such as Naujaat (Repulse Bay) in the 1960s and Salluit in the 1950s.

Initially, the Co-op sold individual works of Oviloo’s to commercial galleries in the South, but her career changed when the Canadian Guild of Crafts in Montreal held her first solo show in June 1981. After this exhibit, Dorset Fine Arts (DFA) in Toronto began to hold her work for solo exhibitions organized by interested commercial galleries.

Two solo exhibitions at the Inuit Galerie in Mannheim, West Germany, in 1988 and 1992, introduced Oviloo’s work to an international audience. The dealers, including Josef Antonitsch, the most important point of connection between Inuit artists and European collectors in the 1980s, saw Oviloo’s work at DFA and asked to show it in Europe. The 1988 exhibition was accompanied by a catalogue that illustrated several bird carvings and those of traditional human subjects, as well as the sea spirit Taleelayu. Then, in 1993, the Burdick Gallery in Washington, DC, organized an exhibition, aptly titled An Inuit Woman Challenges Tradition: Sculpture by Oviloo Tunnillie.

In 1988, Oviloo had begun carving with electric tools. In an interview with curators Susan Gustavison and Pamela Brooks, she mentioned having taken these up after an operation on her arm. Electric tools enabled Oviloo to create sculptures with less effort. During this period, Oviloo, who also had new access to television, shifted the subject matter of her work to include figures from outside Inuit culture, as in Football Player, 1981. She also began to create remembered scenes, including My Mother and Myself, 1990. As she stated in a later interview: “Back in the 1980s, I was asking myself, ‘How will I make art?’ It didn’t make sense to me to carve scenes of traditional life because I was not there. So I began to carve from my own experiences—both happy and sad.”

Another shift occurred in Oviloo’s work in the 1990s, when single female figures dressed in long, flowing robes, as in Grieving Woman, 1997, became frequent subjects. The garments were culturally unspecific and gave prominence to expressive and often emotional body language that verged on the abstract.

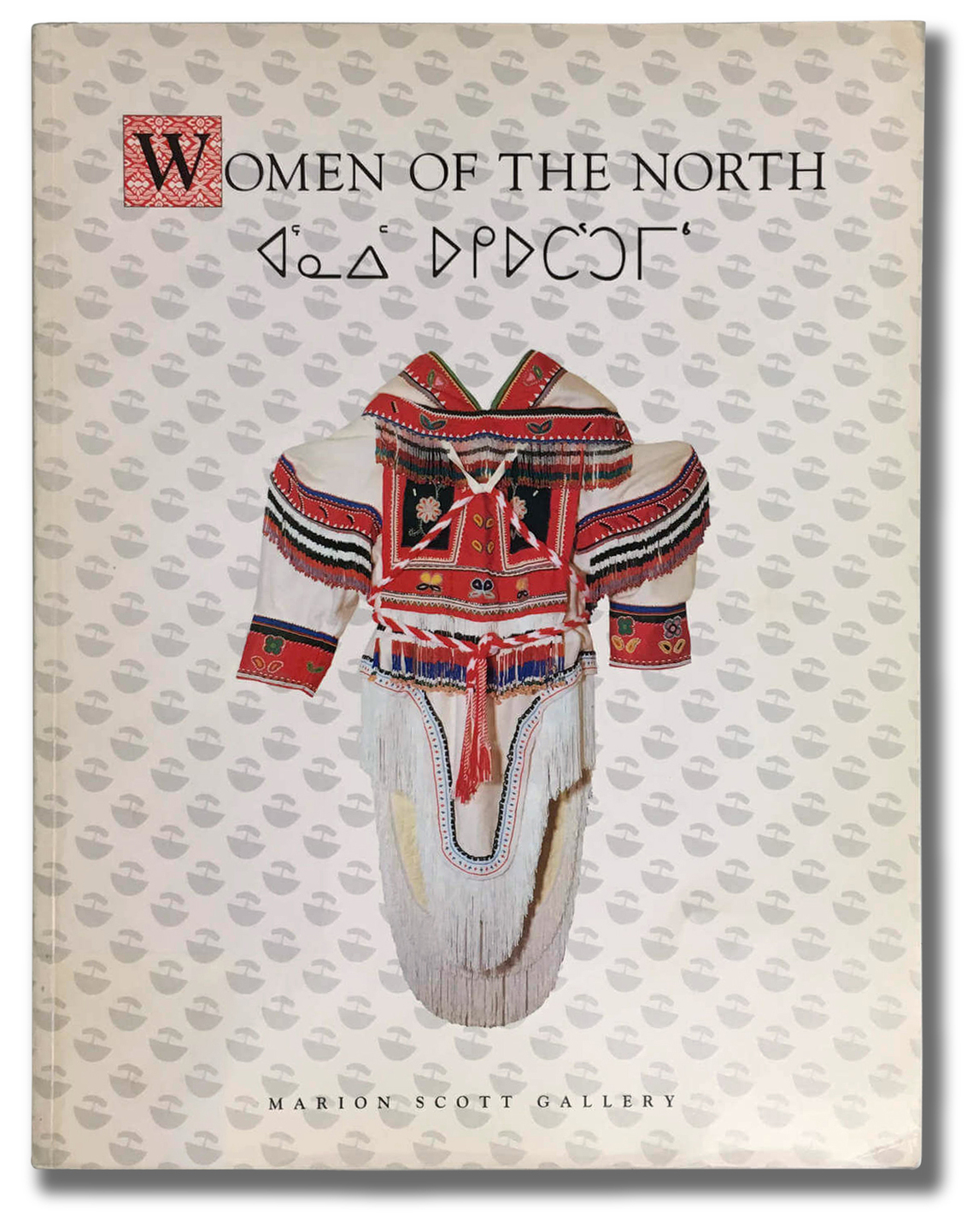

In 1992, Judy Scott Kardosh (1939–2014), director of the Marion Scott Gallery in Vancouver, organized the first of several exhibitions featuring Oviloo’s sculptures. The show was titled Women of the North: An Exhibition of Art by Inuit Women of the Canadian Arctic, and in the foreword to the catalogue, Kardosh explained her ongoing relationship with Oviloo:

I first became aware of Oviloo Tunnillie’s sculpture in the fall of 1991. I had already started the process of selecting pieces for a large exhibition of Inuit women’s art that was scheduled to open at the Marion Scott Gallery the following summer [Women of the North], and some of the suppliers of northern art who were helping me were determined to bring the work of some younger artists to my attention. Oviloo Tunnillie, a relatively unknown sculptor from Cape Dorset, was one of these. I had seen some of her work before—mostly descriptions of wildlife, including some especially skillful depictions of birds. The work I now saw in 1991 was completely different: a young girl in a modern dress beside two veiled women in high heels; a seated woman in the nude, her expressionless face gazing into the distance as though lost in private contemplation. To say the least, this was not conventional Inuit work.

The sculpture described by Kardosh was This Has Touched My Life, 1991–92. The Canadian Museum of Civilization (now the Canadian Museum of History) purchased the sculpture, the first of Oviloo’s works to be acquired by a public art gallery. Kardosh explained that Oviloo’s daring subjects became major highlights of the show, giving it an edge that it would otherwise have lacked. Oviloo came to Vancouver to attend the exhibition’s opening, and during her stay Kardosh discussed with her the possibility of a future solo exhibition.

Within two years, in June 1994, Oviloo produced enough work for a major solo show. Oviloo’s new works dealt with themes such as alienation (Sitting Woman, 1993), Inuit mythology (Diving Sedna, 1994), and sexual abuse (Nude, 1993), with a clear focus on female imagery. Kardosh noted that despite some initial resistance from viewers and Inuit art collectors accustomed to more romantic and traditional representations of northern life, the show, called simply Oviloo Tunnillie, proved to be an important critical and commercial success. These early exhibitions marked the beginning of a highly productive relationship between the artist and Marion Scott Gallery, one that continued for the rest of the decade and resulted in four additional solo exhibitions.

In 1994, the Canadian Museum of Civilization included This Has Touched My Life in a major exhibition and catalogue, Inuit Women Artists: Voices from Cape Dorset, which were curated and edited by Odette Leroux, Marion E. Jackson, and Minnie Aodla Freeman. Several other works by Oviloo—including Hawk Taking Off, c.1987; Woman Passed Out, 1987; and Woman in High Heels, 1987—were purchased by the museum for this landmark exhibition. Nine female artists were featured: six graphic artists and three who created carvings: Qaunaq Mikkigak, Oopik Pitseolak (b.1946), and Oviloo. The catalogue included an insightful autobiography by Oviloo that she titled “Some Thoughts about My Life and Family.”

A Contemporary Artist

A number of publications brought Oviloo Tunnillie’s work to wide public attention in the 1990s. Catalogues were published by Marion Scott Gallery to accompany exhibitions in 1994 and 1996. They included colour illustrations of key works and scholarly introductions by Judy Kardosh’s son and curator at the Marion Scott Gallery, Robert Kardosh. Perceptive articles were written by art critic Peter Millard and published in Inuit Art Quarterly in 1992 and 1994. In 1996 and 2009 art critic Robin Laurence contributed articles about Oviloo’s sculpture to the magazine Border Crossings and placed her work within the mainstream of contemporary art. Commenting on works such as Woman Carving Stone, 2008, and Tired Woman, 2008 (both studies in individual emotions), these writers reflected upon Oviloo’s personal imagery, highlighting how her work’s emotional expressiveness was not culturally specific but universal. Laurence mentions that hands in Oviloo’s sculptures are often disproportionately large and are an important element of expression.

In the 1990s two documentary films were produced that focused on Oviloo’s work, along with that of two other artists in each case. In 1993, Inuit Art Section, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, engaged Connie Cochran and Denise Withers to direct the film Keeping Our Stories Alive: The Sculpture of Canada’s Inuit. It featured two other carvers, Uriash Puqiqnak (b.1946) from Gjoa Haven, Nunavut, and Lucy Meeko (1929–2004) from Kuujjuaraapik, Nunavik. On November 12, 1997, a wide television audience viewed Adrienne Clarkson’s episode “Women’s Work: Inuit Women Artists” on the weekly program Adrienne Clarkson Presents. Clarkson travelled with her film crew to Cape Dorset and Holman (now Ulukhaktok) to interview Oviloo, as well as Oopik Pitseolak and Elsie Klengenberg (b.1946).

As Clarkson explains in her introduction, “My fascination with Inuit women artists was ignited by a recent exhibition of the work of Oviloo Tunnillie. Her carvings seem to embody both the heartbreaking and the irreverent, and they displayed a kind of elegant simplicity that left me awestruck.” The exhibition Clarkson references was at Marion Scott Gallery, and Oviloo’s heartbreaking and irreverent work would have surprised viewers whose idea of Inuit art was likely based on the conventional subject matter of most artists at the time. Oviloo’s responses to Clarkson’s questions were possibly equally eye-opening; she explained that her carving, Nude, 1993, was actually about the sexual assault she had experienced when in the hospital in Manitoba (likely the Clearwater Lake Indian Hospital). The stricken figure lays on her back with a hand protectively covering her groin. “This one is about child molestation. I have gone through that experience when I was a little girl.”

The excitement generated by the broadcast of Clarkson’s film was soon replaced by sorrow. At the age of thirteen, Oviloo’s youngest daughter, Komajuk, committed suicide while the family was gathered watching television in another part of their house. In response to this devastating loss, Oviloo created her first Grieving Woman, in 1997, marking a significant turning point in her life and her career. In her work that followed, Oviloo would return again and again to figures of women gripped by versions of this sadness.

Beyond Cape Dorset

Starting in 2000, Oviloo Tunnillie’s family moved several times over a five-year period, first to Toronto, and then to Montreal, with stops in Ottawa. According to Iyola Tunnillie, he was the first to travel to Toronto in 2000. He accompanied his youngest son, Etidloi, who was receiving a medical assessment for mental health issues. They had to stay in the city for Etidloi to undergo a prolonged period of treatment and stabilization with medications. Oviloo joined the men in Toronto in 2000 or 2001, along with her eldest son, Tytoosie, and adopted granddaughter, Tye. The sculpture Self-Portrait (Arriving in Toronto), 2002, shows Oviloo with a suitcase at the Toronto airport. Her short-sleeved dress reflects her arrival into a new southern culture.

In the South, Oviloo ordered stone from the Co-op in Cape Dorset and carved to support her entire family. They lived in rooming houses, and Oviloo likely worked wherever they lived. She created many of her female torsos during this period. Another notable Inuit carver, Ohito Ashoona (b.1952), was also living in Toronto at the time and provided the family with some assistance, including giving Oviloo carving stone.

The financial pressure of supporting her family in the city had a detrimental effect on Oviloo’s work. John Westren, who was employed at Dorset Fine Arts in Toronto at the time, remembered: “A number of Inuit told her she could do so much better in the South, but it didn’t work out and her work suffered. Her whole family eventually came down and she was the sole breadwinner. She had to whip off some very pedestrian things, some very repetitive work, standard women kneeling and praying. . . . [DFA] didn’t buy much of her work while she was in Toronto.”

While in Toronto, Oviloo and her husband attempted to sell work directly to tourist-oriented stores such as Eskimo Art Gallery on Toronto’s Harbourfront. However, as Westren explained: “The tourist industry dried up after 9/11 [2001] and tourists stopped crossing the border. Also, the gallery didn’t buy much of Oviloo’s work because it didn’t appeal to tourists.”

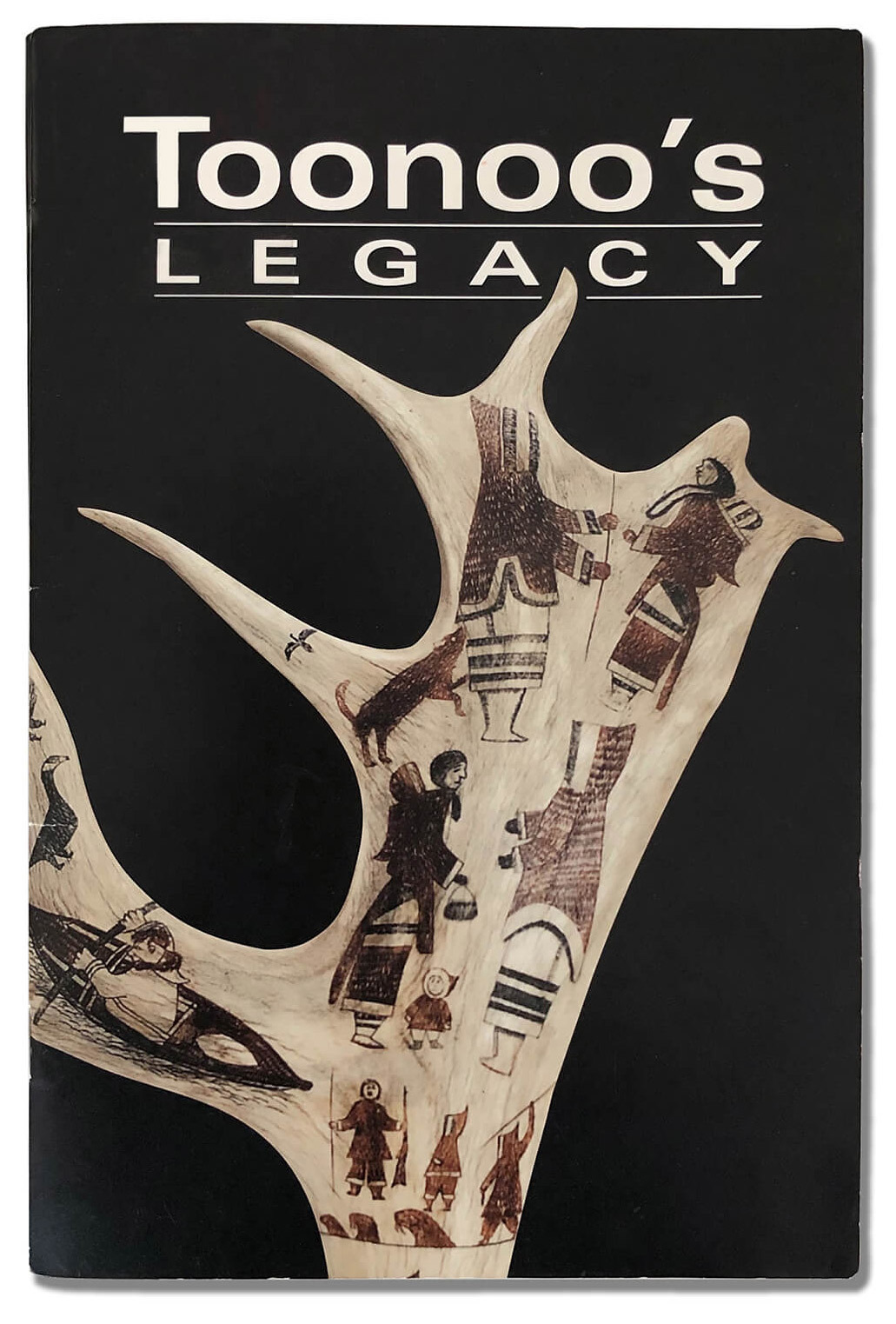

Nonetheless, in November 2002, the Toronto gallery Feheley Fine Arts organized the exhibition Toonoo’s Legacy, featuring art by members of Oviloo’s family, including her parents, Toonoo and Sheokjuke; Oviloo herself; her brothers Sam and Jutai; and her sons Tytoosie, Noah, and Etidloi. Most of the family attended the opening. Two of Oviloo’s carvings in this exhibition were nostalgic memories of her father: On My Father’s Shoulders, 2002 and Ataata, 2002, the Inuit term of endearment for “father.”

After more than a year in Toronto, the family gradually moved to Montreal between 2002 and 2005, and independently sold their work to Galerie Elca London and several other buyers and entrepreneurs. In the spring of 2003 Oviloo travelled to Vancouver for the filming of a documentary about her work for the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN). She returned to Cape Dorset permanently in 2006 after the death of her sister Nuvalinga’s daughter. Iyola soon joined her, and their children have divided their time between North and South ever since.

Soon after Oviloo’s return to Cape Dorset, she discovered that she had ovarian cancer and was forced to stop carving while undergoing treatment. She had become estranged from Judy Kardosh and Marion Scott Gallery after her move to the South, but she re-established the relationship after returning to Cape Dorset and during her illness.

From October to November 2008 an important new exhibition, Oviloo Tunnillie: Meditations on Womanhood, revealed that Oviloo’s strength and imaginative powers had returned. Some of her most emotionally expressive works were included in this exhibition, such as Tired Woman, 2008; Woman Carving Stone, 2008; Woman with Stone Block, 2007; and Sedna, 2007, a very human study in fatigue. This was the last creative collaboration between the gallery and the artist. Both women suffered declining health, Kardosh with complications from diabetes and Oviloo with her recurring cancer. Kardosh passed away in November 2014.

For the last two years of her life in Cape Dorset, Oviloo was unable to work, and she succumbed to cancer on June 12, 2014.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements