Oscar Cahén lived a brief but intense life. Although he worked in Canada for only fourteen years and exhibited his paintings for a scant eight, his role in the development of both illustration and abstract painting in Canada was pivotal. He gave fellow artists and designers confidence to experiment and to stand up to conservative backlash, setting an inspirational example with his engaging art.

After his death, Oscar Cahén’s oeuvre and personal papers were not available for many years, and not much was known about his life, creative process, and thoughts on art. As a result, comparatively little in-depth research on him has been completed, and the assessment of Cahén’s contribution to Canadian art and design has been largely based on people’s fond memories and on erroneous reports (some given by the artist himself, some from faulty journalism, some from well-intentioned but mistaken friends). Recently, Oscar’s only child, Michael Cahén, has done much to right the situation by establishing The Cahén Archives, which now enables scholarship to proceed. New research has corrected much of the record and is confirming that Oscar Cahén played an instrumental part in revitalizing illustration and legitimizing abstract art in Canada.

As a visual communicator bound up in networks of social alliances, business, institutions, and technologies, the artist is a mediator of the zeitgeist, uniquely positioned to select some elemental idea and re-present it to the community in new contexts, renewing, adjusting, or inventing meaning in the process. Oscar Cahén did not theorize about painting very much, preferring instead to act instinctively. When asked what his abstract pictures meant, he retorted: “Why don’t you go out and ask a bird what his song means? I’m not interested in telling a story . . . when I paint, I set down the pushing and pulling of my emotions.” But his friend Harold Town (1924–1990) saw in Cahén’s work a “voracious appetite for living . . . [expressed in] joyous colour . . . [and] forms that suggest growth in exultant upward thrust . . . a sense of his deep concern with the life force.” This expression of surviving and thriving encapsulates not just Cahén’s life but also Canadians’ postwar energy and rapid economic and cultural development.

“Painting can be capable of transmitting emotions beyond the representational value therein, and consequently [can] influence the onlooker,” Cahén wrote. Visual power in media could “contribute actively towards the cultural development of our society.” Born during the First World War, coming of age in the Nazi era, and living during a period of enormous social and technological change, he was well placed to express the times: as an editorial illustrator of war and daily life; as a painter of themes of trauma and rebirth; as a producer of abstract works that were said at the time to be expressive of modern life.

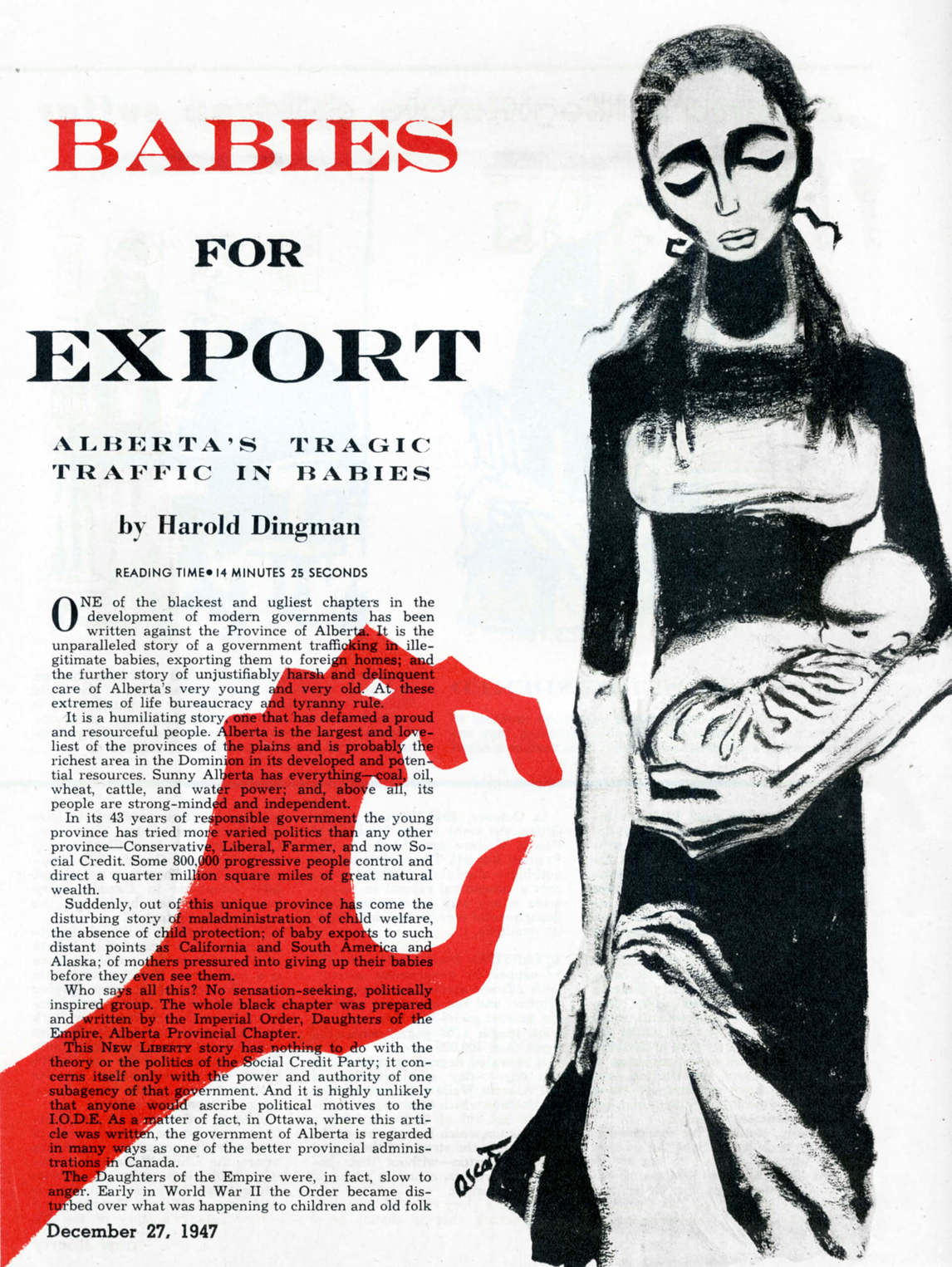

Cahén’s illustrations run from the documentary to the wholly imaginative. Even the most whimsical give insight into daily events, into the things people wore and had in their homes, and into their relationships. With his commercial illustration, Cahén affected public opinion and social values by means of charm or horror. His illustration for an investigative journalism article on the alleged trafficking of babies of unwed mothers in Alberta features a menacing claw reaching toward a despondent woman, rendered in a flattened, hard-edged and angular manner. One reader complained, “The drawings . . . resemble the doodlings of a surrealist the morning after.”

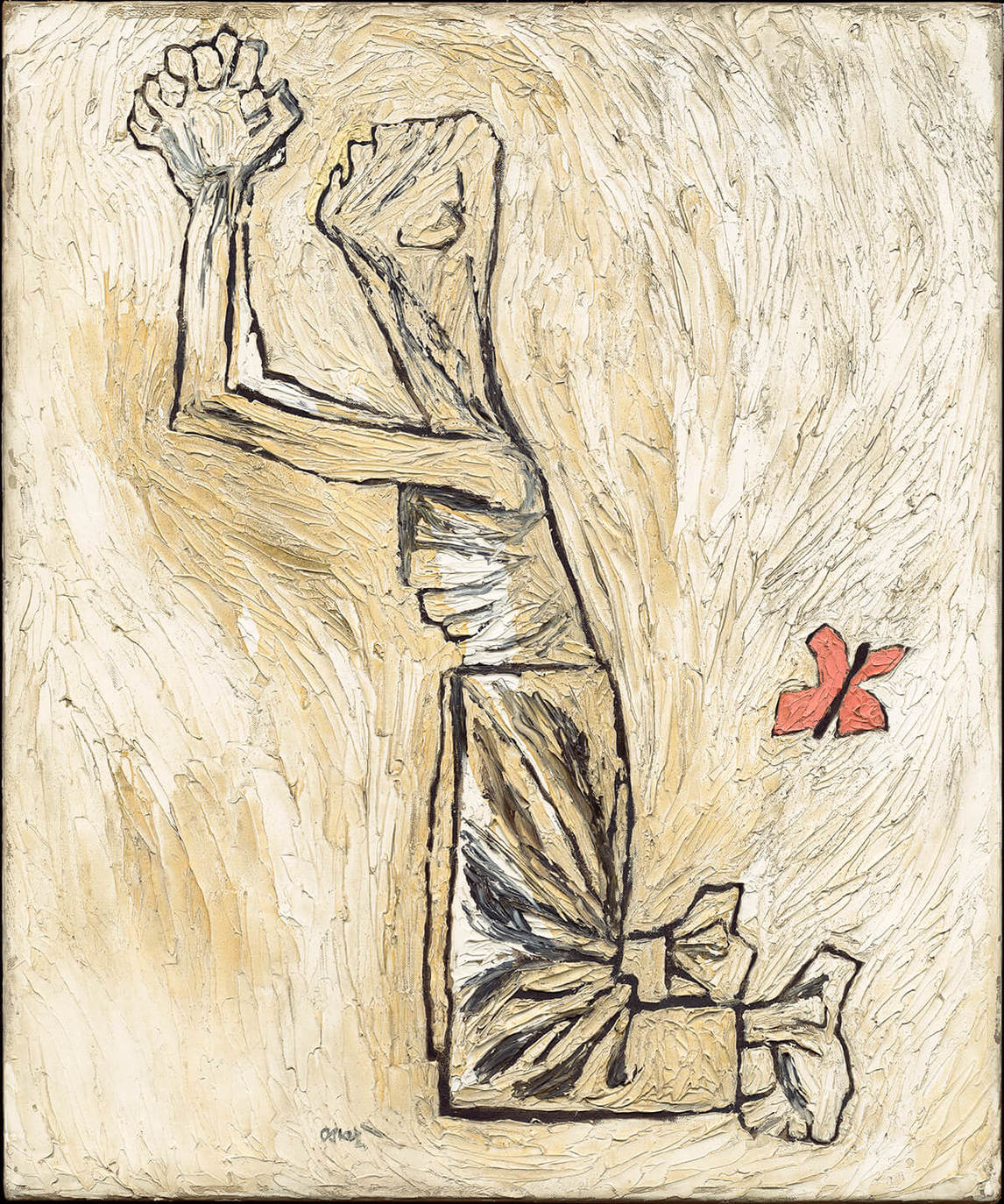

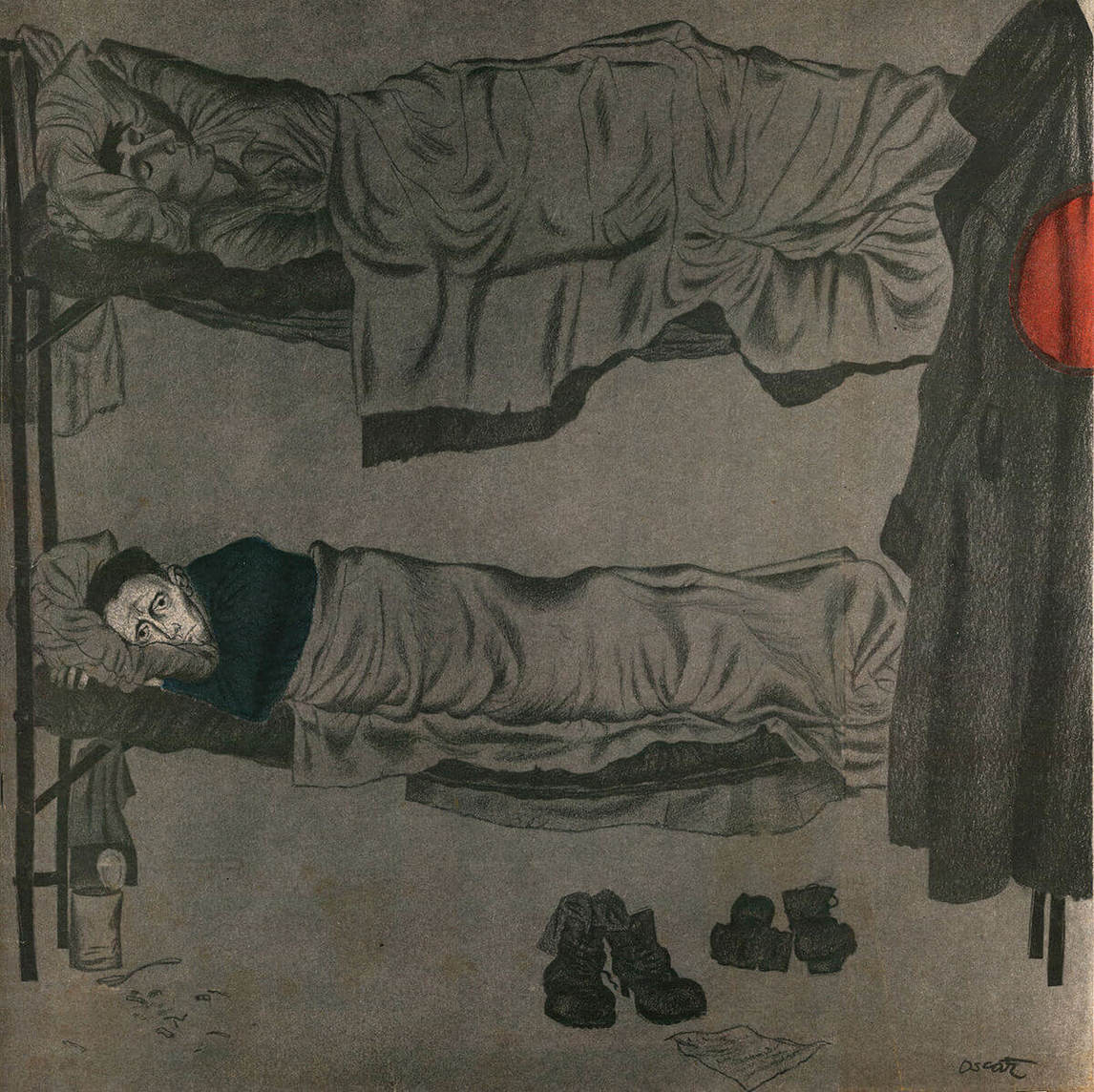

In the paintings of suffering figures or with religious themes that Cahén painted from 1946 to 1951, such as Praying Man, some viewers see an archetypal expression of communal Jewish experience. It remains to be seen how much of Cahén’s point of view can be ascribed to his part-Jewish ethnicity; when filling out forms, he always gave his religion as “none.” Yet whether Cahén thought of himself as part-Jewish or not, he had been treated like a Jew in Europe and in the British and Canadian refugee camps, and he maintained a connection to Toronto’s sizeable and culturally important Jewish community through friendships with other ex-interns and his work on the largely Jewish-staffed Magazine Digest. Given the systemic oppression of Jewish people in Canada during the postwar period, it can be argued that some of Cahén’s works were superficially aimed at general audiences but were subtly coded for a different reading by those who understood his background more intimately. The scarlet circle on the back of a jacket in a Maclean’s illustration—a reference to the internment camp Cahén endured—can be read as one such coded message. Images such as Praying Man, 1947, which was accepted to the 1947 Ontario Society of Artists exhibition, spoke to a general postwar audience as easily as to an individual or a defined group because, like his depictions of Christ, it captured lament and rejuvenation at the same time.

For its fans, abstract art signified Canada’s growing equivalence to the cultural sophistication of the United States and Europe. Modern artists’ experimentation met with the optimism and affluence of the postwar period when Canadians’ receptivity to new art forms was cracking open. At the same time, the Cold War was descending, bringing with it rampant fears of communism and nuclear weapons. Meanwhile the trauma of returning veterans, the acceleration of transportation, communication, and business, and advances in science were affecting everyday life and adding new stresses. In art, people were preoccupied with the idea that old ways of painting could not adequately reflect such a changed society.

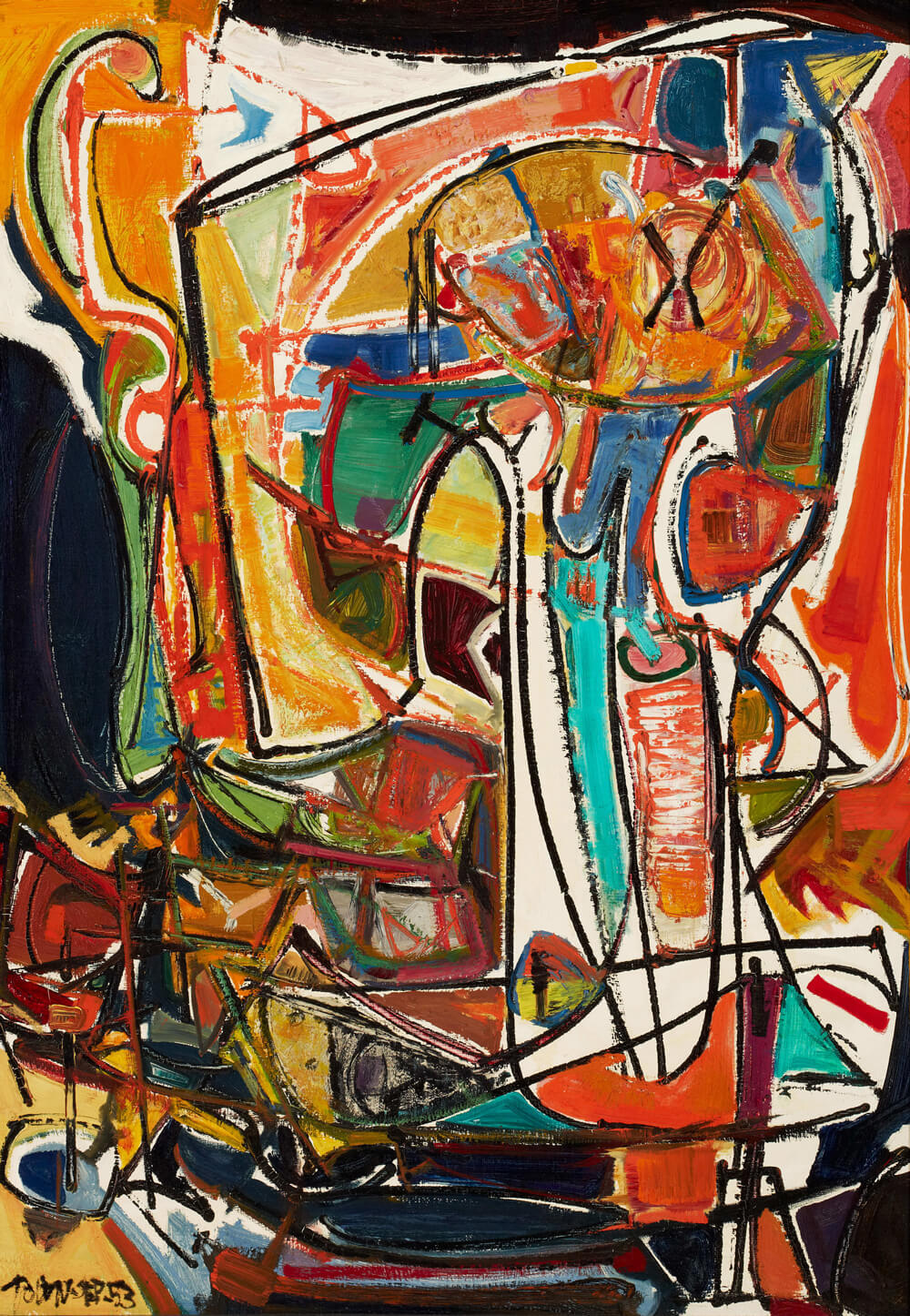

The disorienting break with the past alongside lingering memories of the Depression and Second World War atrocities meant that expressions of feeling in colour, rhythm, and shapes allowed for more personal interpretation and processing of emotion than did realistic depictions. Take, for example, the radiantly thrusting Traumoeba, 1956, whose title amalgamates the word trauma, the German word traum (dream), and the word amoeba. The licence of the artist to act outside of convention symbolized the right of all individuals to self-determination in a democratic society. Yet Cahén’s paintings frequently brought chaos under the yoke of design, containing his wild gestures and vibrating colour combinations in taut, compartmentalized, carefully balanced compositions. Cahén’s work can be seen to signify a humanistic hope for a kind of orderly freedom of expression in a tolerant, progressive Canada.

Reception in Design

After only four years as a paid commercial artist, Oscar Cahén was already “generally considered one of the best freelancers in Canada.” Canadian art books first mention him in 1950 and 1952. Between 1949 and 1957, he received five medals and six awards for illustration, and his work was featured in the New York Art Directors’ annual exhibition and in several European design journals. Canada’s most accomplished designer, Carl Dair (1912–1967), noted that Cahén held a “pre-eminent position.”

Cahén’s biography parallels that of émigré artists in the United States such as Marcel Breuer (1902–1981), Leo Lionni (1910–1999), and Max Weber (1881–1961). Some scholars have supposed that Cahén must have been, like them, a conduit for transmission of European modernism. However, it is difficult to gauge his actual experience with Cubism, Expressionism, or the Bauhaus teachings because little is yet confirmed about what he saw before coming to Canada in 1940. But no matter what his actual intimacy with experimental art was, by 1947 Cahén was exhibiting an Expressionist canvas at the Ontario Society of Artists’ annual exhibition, and his oil painting Christus, c. 1949–50, was held up in the press as the most quintessentially modernist work in a 1950 Royal Canadian Academy exhibition.

By 1950 Cahén was sending Canadian illustration samples by his peers to the prestigious Graphismagazine in Zurich, thus forming a tangible link between the Canadian artists and Europe. His role as a trans-Atlantic intermediary, his proclivity for calling most slick advertising art “American junk,” and his belief in the power and social responsibility of commercial artists fit with the rhetoric of the postwar design reformers who wanted Canada to prosper along modernist, anti-American lines. He figured in design criticism as an example of Canadian sophistication that was consistent with the movement toward the professionalization of graphic design along international—meaning European, especially Scandinavian and Swiss—lines. As art director Stan Furnival (1913–1980) was to say in 1959, “With a sense of freedom and vitality, [Cahén’s illustrations] radically changed a tight slick Americanized attitude almost overnight. . . . Oscar realized that Canada was probably the only country left in the world where a fresh, alive influence would not only be accepted, but praised and honoured.”

A less politically invested view today must concede that Cahén’s illustration was more culturally hybridized than his contemporaries cared to admit. Although his work initially appeared “typically European,” he had already absorbed American illustration in Prague and Germany, where Americana was in vogue, and it is more accurate to say that he combined European, American, and Canadian influences.

Nevertheless, the design awards he won from juries of his peers were based firmly on his technical and creative prowess, not his ethnicity. Cahén certainly impressed everyone with virtuosity: junior artists delighted in timing how fast he could whip off a figure (about seven minutes). Younger illustrators Gerry Sevier (b. 1934) and Tom McNeely (b. 1935) kept his work pinned up in their studio. A letter from art director Dick Hersey (dates unknown) once advised Harold Town (1924–1990), “[Your] drawing is too involved, also highly reminiscent of Oscar. I prefer to go to the source.” Since the first exhibition of Cahén’s illustration art in 2011, and with the circulation of the exhibition’s catalogue, a new following of contemporary illustrators and comics artists has begun to grow.

Reception Among Painters Eleven and Others

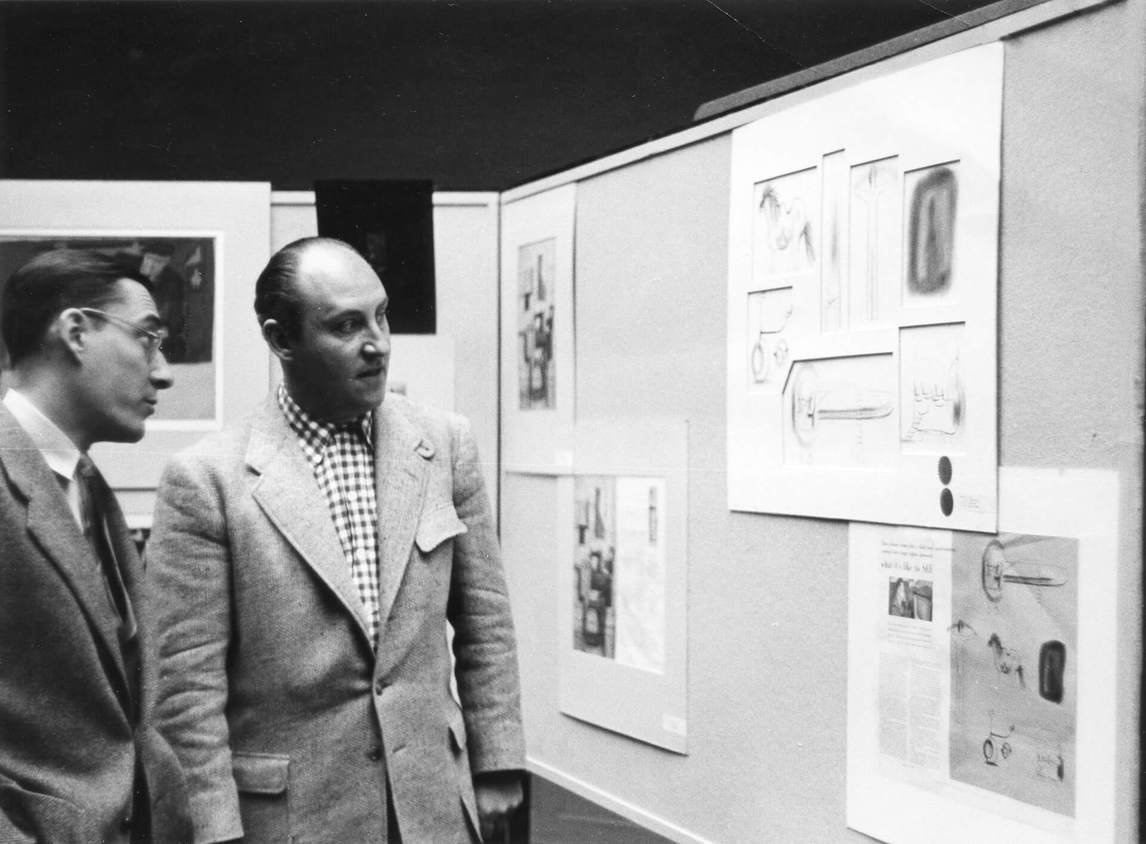

Oscar Cahén’s memory is inevitably linked to his participation in Painters Eleven, an artists’ group whose promotion of abstract painting and artistic freedom was described by critic Paul Duval in 1957 as having “performed a service for Canadian art.” What Cahén brought to the group, member Jack Bush (1909–1977) stated, was “a wonderful sense of European colour and daring, but with it was also the wonderful tolerance and understanding.” Again owing to his background, Cahén held a powerful place in Painters Eleven, for he helped give the group a semblance of international flair that set them apart. When countering accusations that Painters Eleven was derivative of the New York School, for instance, member Ray Mead (1921–1998) could conveniently point out that Cahén’s paintings looked “German.” Cahén once more acted as trans-Atlantic intermediary, helping member Jock Macdonald (1897–1960) scout opportunities for a Painters Eleven show in Europe by writing to venues in Germany. Cahén’s foreign identity gave the Painters Eleven group an air of authenticity, authority, and legitimacy that commanded respect in the face of the snide remarks their abstracts received in much of the press. Through Cahén, a European flavour was thought by one critic to have been passed on to Toronto painters at large.

Many historians and critics have found that Cahén—nicknamed “Doc” by his friends for unknown reasons—commanded considerable influence in Painters Eleven and among other Toronto artists. Some have compared his role to that of the eminent Jock Macdonald; fellow member Tom Hodgson (1924–2006) even felt that “Cahén was by far the giant of the group,” although it had no leader per se. Upon hearing of Oscar Cahén’s death, the artist Toni Onley (1928–2004) wrote, “Some did not always agree on his departure in painting, but he taught us to re-examine ourselves—and thinking, find a mind’s-eye—and through this his boundless imagination and resourcefulness has rubbed off on us young painters.”

Cahén is especially recognized for his colour. First noted in 1952 to be “subtle,” his palette then underwent a shift, and the words used to describe it—astonishing, unexpected, striking, intense, joyous, peculiar, eccentric, and uncommon—demonstrate that for Torontonians of the early 1950s this new colouration was unusual. Jack Bush noted that Cahén introduced a pastel palette into Toronto. In one of the more critically rigorous pieces written in the period, Clare Bice asserts that “the spirit of OC still dominates and motivates the group,” and accuses other members of producing “derivative exercises . . . reflecting the dominant inspiration of Cahén”—two years after he had died. Scholars have found that Cahén had a particular impact upon Harold Town (1924–1990), Jack Bush, Tom Hodgson, Ray Mead, and Walter Yarwood (1917–1996). The competitive instinct in both Town and Cahén stimulated each, and Cahén’s passing interest in printmaking also spurred Town into exploring that medium. Upon news of Cahén’s death, William Ronald (1926–1998) told Jock Macdonald privately, “When I was attending college I would eagerly await the arrival of each local exhibition to see Oscar’s latest work. He was working in a creative manner in a mature way and on a grand scale before most of us.” According to Mead, Cahén “used dyes on large sheets of paper, and his drawings. It had a bit of influence on all of us. You could say a bit of Oscar would turn up in all of us eventually.”

A Career Cut Short

In 1975 Oscar Cahén was posthumously awarded the Royal Canadian Academy Medal to honour his contribution to Canadian art. The Canadian Association Of Professional Image Creators (CAPIC) awarded their Lifetime Achievement Award to Cahén in 1988.

Attempts to hypothesize Cahén’s unrealized future are irresistible. But should one indulge? In the catalogue of the 1983–84 Oscar Cahén retrospective, David Burnett wisely advises not to focus on what Cahén might have done had he lived longer, because the fictional masterpieces we extrapolate in our imagination will always unfairly diminish the works he did leave us—paintings such as Subjective Image, c. 1954, which summarizes Cahén’s dramatic colour sense and characteristic iconography in a succinct composition.

It is exactly such speculation that can lead one, mulling over Cahén’s diverse works and early death, to conclude that he might not have reached artistic maturity. But here the concept of “maturity” is flawed: it assumes the artist must refine and sustain a unique mode of self-expression. This expectation has been greatly promoted by the art market, which thrives when an artist becomes known for an easily spotted, brand-like “signature style.” The risk is that this bias could oversimplify or erase aspects of the artist’s full range of art activities and quash promising but unfashionable creative potential.

A narrow, focused effort is not valid for all artists—Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), for instance, never stayed in any one vein of work. Cahén remained ever curious, pressing visual exploration in all directions, returning as needed to earlier and concurrently developing forms. Cahén’s bodies of work can be considered complete and interrelated entities rather than sequential steps toward some unrealized goal. That Cahén’s own peers in the 1950s accepted them as advanced accomplishments rather than preparatory trials should satisfy us today that his quality is stable and consistent, a factor that transcends mere stylistic constancy.

It is the strength and fecundity of the artworks Oscar Cahén left us that validate his multi-disciplinary approach as a fully rounded visual research methodology. The “tremendous scope of his magnificent painting talent,” as one reviewer put it in 1960, is what make him a pivotal figure in Canadian art, and it is the contribution by which we may appreciate him most.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements