Oscar Cahén (1916–1956) arrived in Quebec from Europe in 1940 as an unwilling refugee. Yet in a few short years the vibrant and emotionally complex artist would broaden the scope of illustration and painting in Canada. Cahén died suddenly in 1956, but not before rising to be one of the nation’s most celebrated illustrators as well as a major influence on fellow abstract painters, with whom he formed the renowned artist collective Painters Eleven.

Child of Many Nations

There exists a photograph of a grinning, teenaged Oscar Maximilian Cahén and two unidentified companions taken at the Zwinger Palace in Dresden, Germany. Young Cahén had used a fake birth date in order to gain acceptance into Dresden’s State Academy for Applied Arts in March 1932, at the age of sixteen. The photo, with a corner now ripped away, bears the scars of the upheaval soon to come: Nazi aggression precipitated his family’s departure from Germany, then his separation from his parents, and his eventual arrival in Canada as an interned refugee.

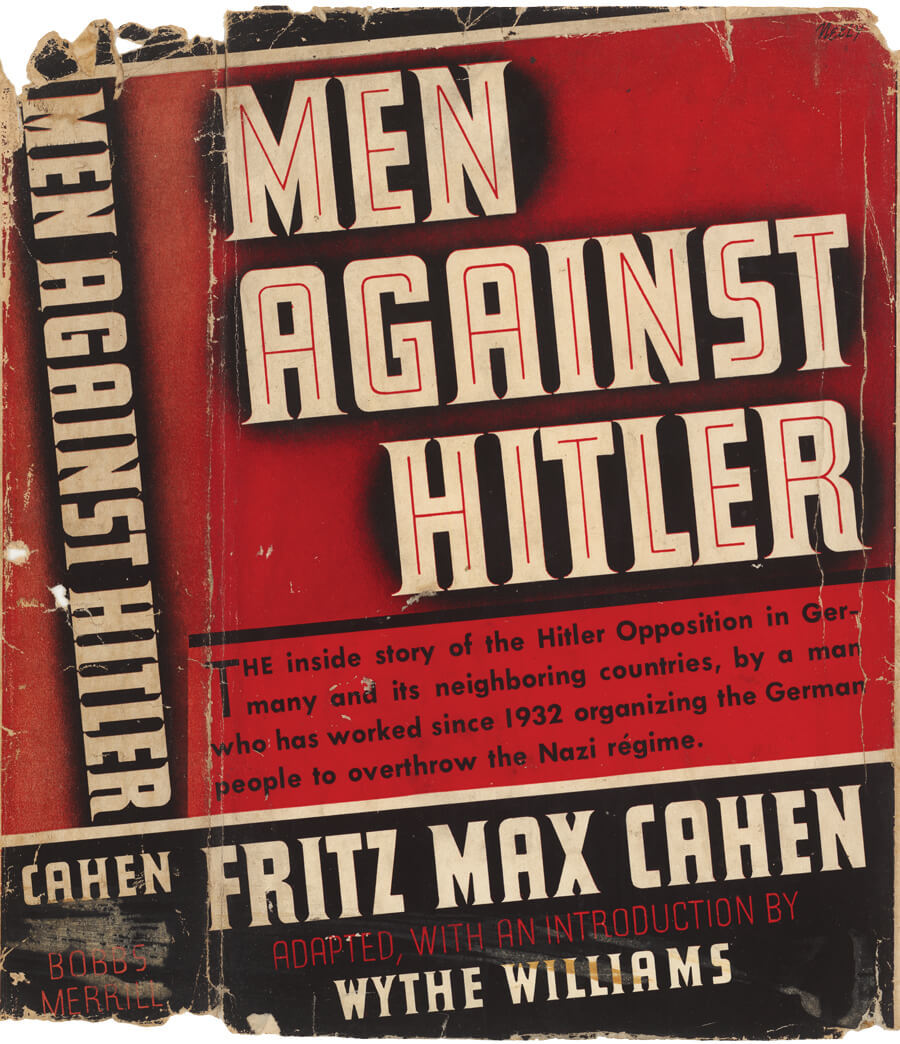

Oscar was born to Fritz Max and Eugenie Cahén on February 8, 1916, in Copenhagen; his Jewish father was first a professor of art history and then a prominent Copenhagen correspondent for the German newspaper Frankfurter Zeitung. Fritz Max Cahén also translated the works of Apollinaire for the Expressionist periodical Der Sturm and published art criticism. By 1916 he was a confidant of and assistant to Count Brockdorff-Rantzau, who represented Germany during the negotiation of the Treaty of Versailles. Fritz Max also became involved in espionage during the war.

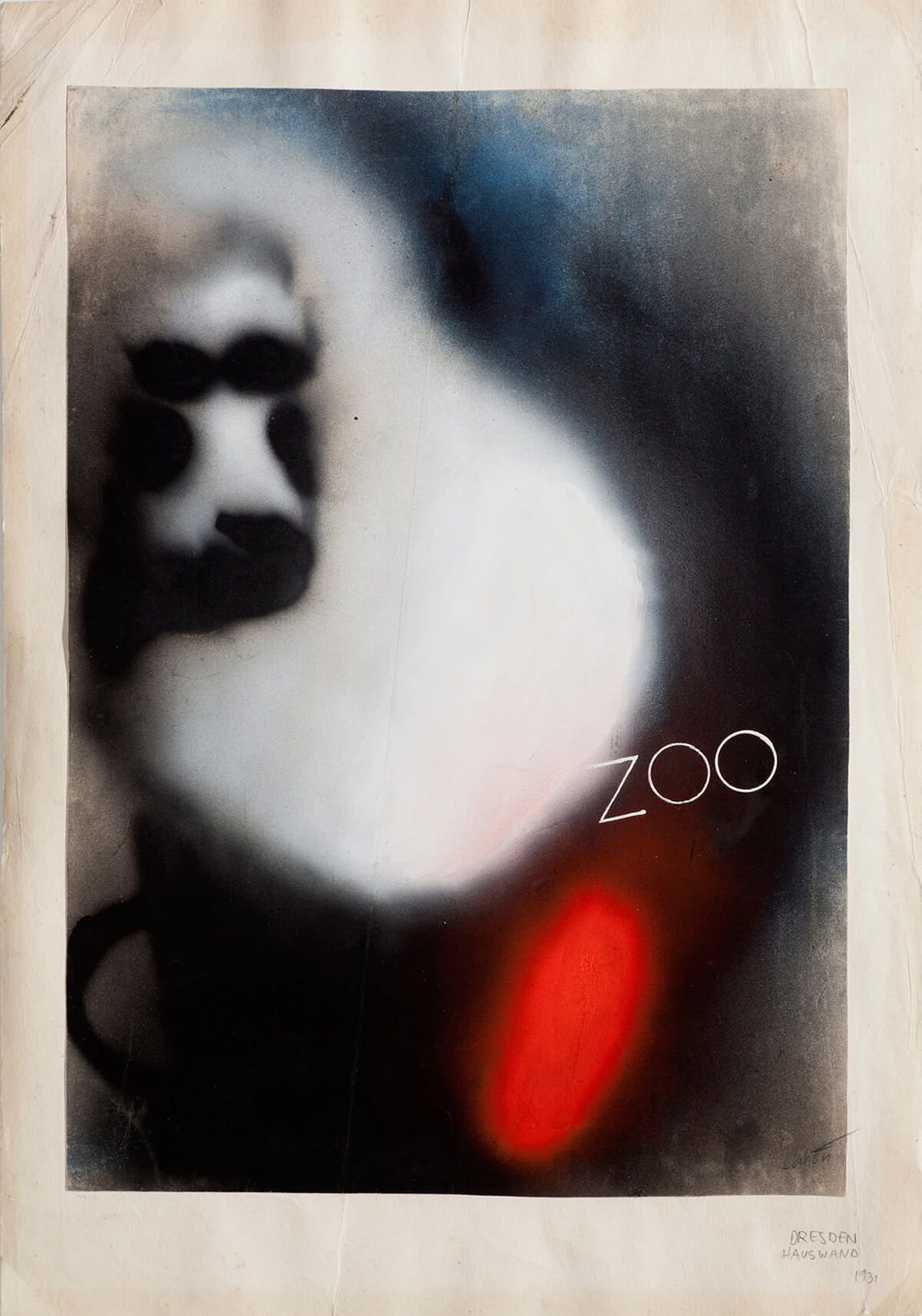

From 1920 to 1932 Fritz Max Cahén’s journalism work brought the family to Berlin, Paris, and Rome. Adolescent Oscar studied art in the latter two cities, but no details are at present known. In Dresden, Oscar took illustration and commercial art instruction in the Academy studio of Max Frey (1874–1944). At this time, advertising and popular illustration were thought by many to be the art of modern times. Posters were considered “art for the people,” decorating outdoor space and improving the public’s aesthetic sophistication.

On the Run

Fritz Max Cahén, a Social Democrat, was assaulted when he attempted to address a Nazi meeting in 1930. Two years later, he began collaborating with an underground network to oppose Hitler. In 1933, when the Nazi Party rose to power, the Cahéns’ German citizenships were revoked because of Fritz Max’s Jewish blood.

Pursued by forty storm troopers, the family stole out of Dresden on August 3, 1933—with Oscar in “a state of nerves” so bad that his father feared it would betray their intent to defect at the Czech border. By May 1934 the Cahéns had shifted to Stockholm, where Oscar continued to study art. He also mounted a solo exhibition in Copenhagen that attracted reviews offering encouragement for his “refined advertising art.”

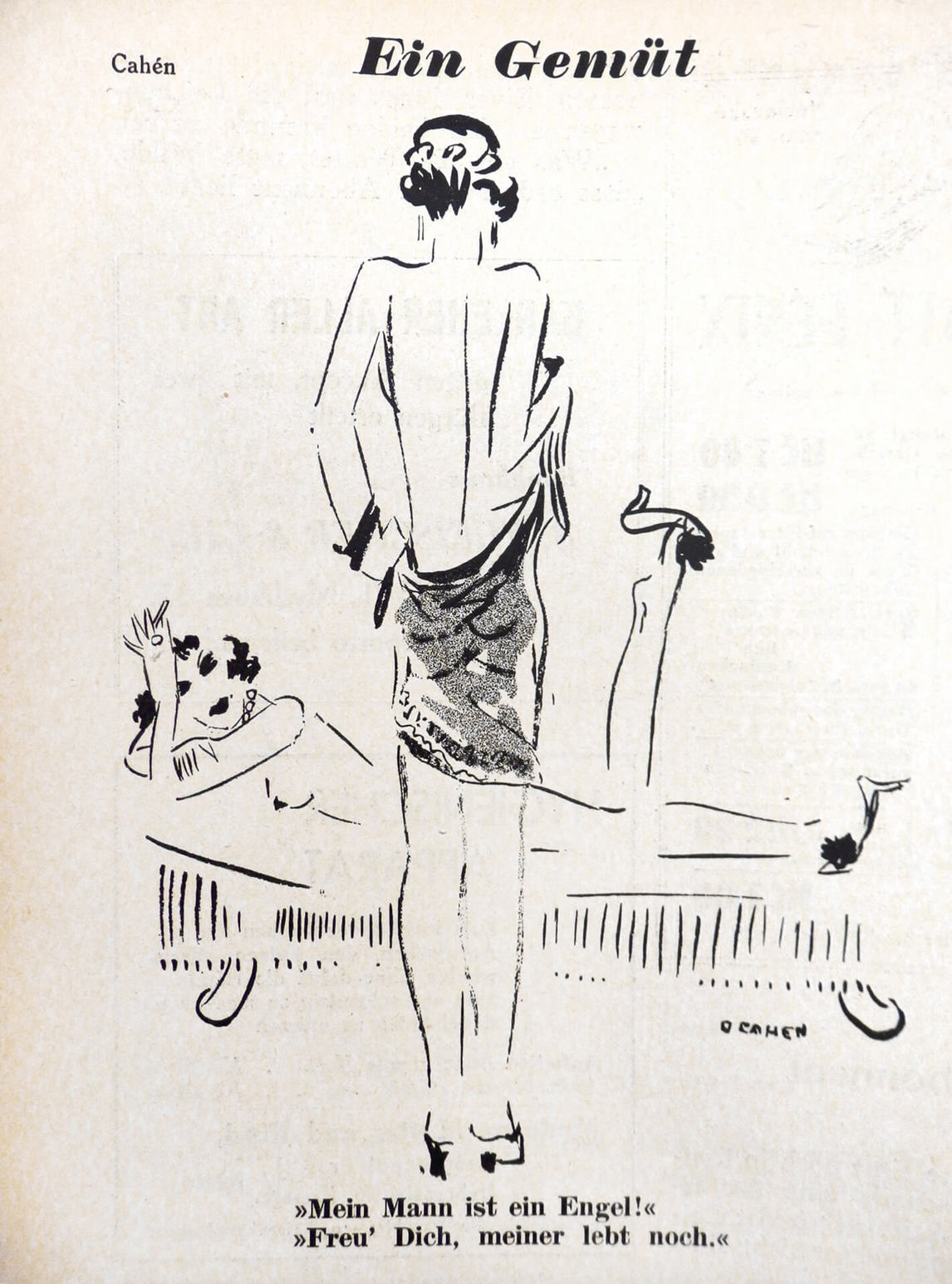

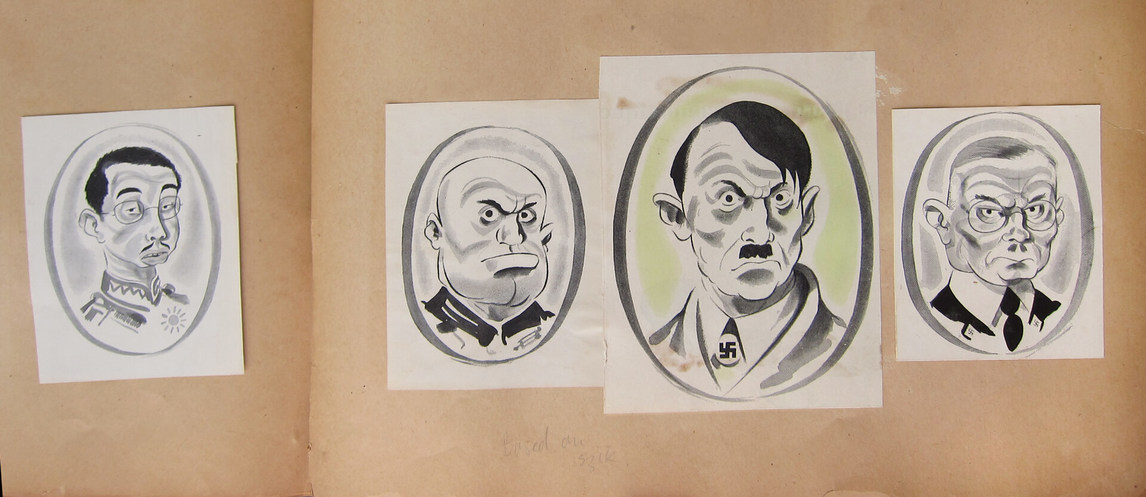

The Cahéns returned to Prague in March 1935, where Fritz Max Cahén led a resistance group—and resumed espionage. Oscar contributed to the desperate family finances with advertising art commissions, erotic drawings, and cartoons. Many were anti-Hitler jokes. One, published in the German refugees’ satirical magazine Der Simpl, shows two semi-nude women. The first says, “My husband is an angel,” to which the other replies, “Rejoice, mine is still alive!”

Impoverished, Oscar was graciously given some studio space by William Pachner (b. 1915), an established illustrator who later moved to the United States. Oscar and Pachner formed a partnership, and Oscar quickly absorbed Pachner’s fluid style.

Oscar not only became a member of his father’s group but also assisted by illegally crossing the border into Germany for unknown purposes, and helped complete an arms deal his father brokered. In 1937 Czech police interrogated the Cahéns about illegal short-wave radio equipment in Oscar’s possession (for broadcasting anti-Nazi propaganda) and searched their apartment. Soon after Fritz Max travelled to the United States, ostensibly to write about American democracy for a Czech paper. It would be twenty years before he and Eugenie would be reunited.

In mid-1937 Oscar began working and teaching at the Rotter School of Advertising Art in Prague and working at the related Rotter Studio. This large ad agency founded by Vilém Rotter (1903–1960), one of the most progressive graphic designers in Europe, handled automobile industry and other big accounts. But Oscar was forced to quit after a few months because the state did not permit refugees to work. He therefore planned to emigrate to the United States.

Instead, Oscar and Eugenie made a narrow escape to England on March 3, 1939—twelve days before Nazi occupation of Prague. Czech officials who remembered Fritz Max’s service got them passports, but only with difficulty because of Oscar’s involvement with the radio and arms deal.

Wartime in Quebec

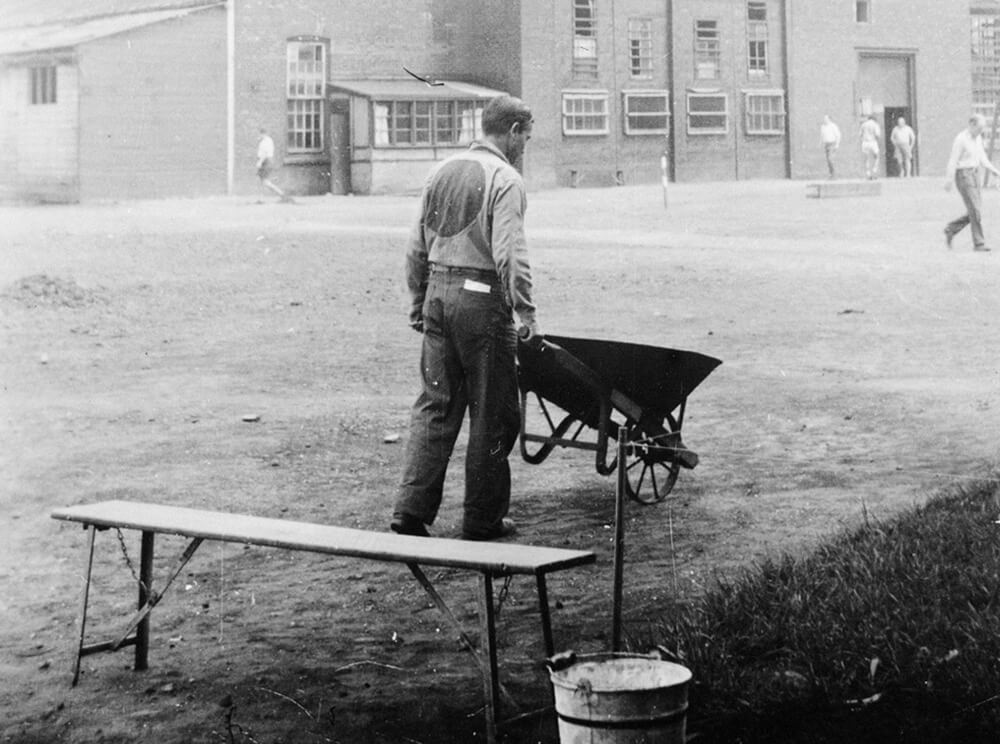

Cahén was prohibited from working in Britain too, but he kept drawing. In May 1940 the British government began to detain refugees, lest they be German spies. Twenty-four-year-old Cahén was loaded onto the prison ship Ettric with over two thousand mainly German Jewish men officially classed as prisoners of war and enemy aliens. They arrived in Montreal on July 13, 1940. Eugenie, too, was interned from May 1940 to December 1941, in Great Britain. They were not to see each other again for seven years.

Among Oscar Cahén’s effects is a poem that he wrote in German:

I’m living in the filth of an old factory. . .

I have a courtyard and a machine hall,

Guards and a barbed wire fence.

We are 700 of us, and can only

Look out over it angry and swearing.They feed us well and dress us warm

And look past us with contempt.

Never before in our lives were we so poor –

And what’s more once we were free.

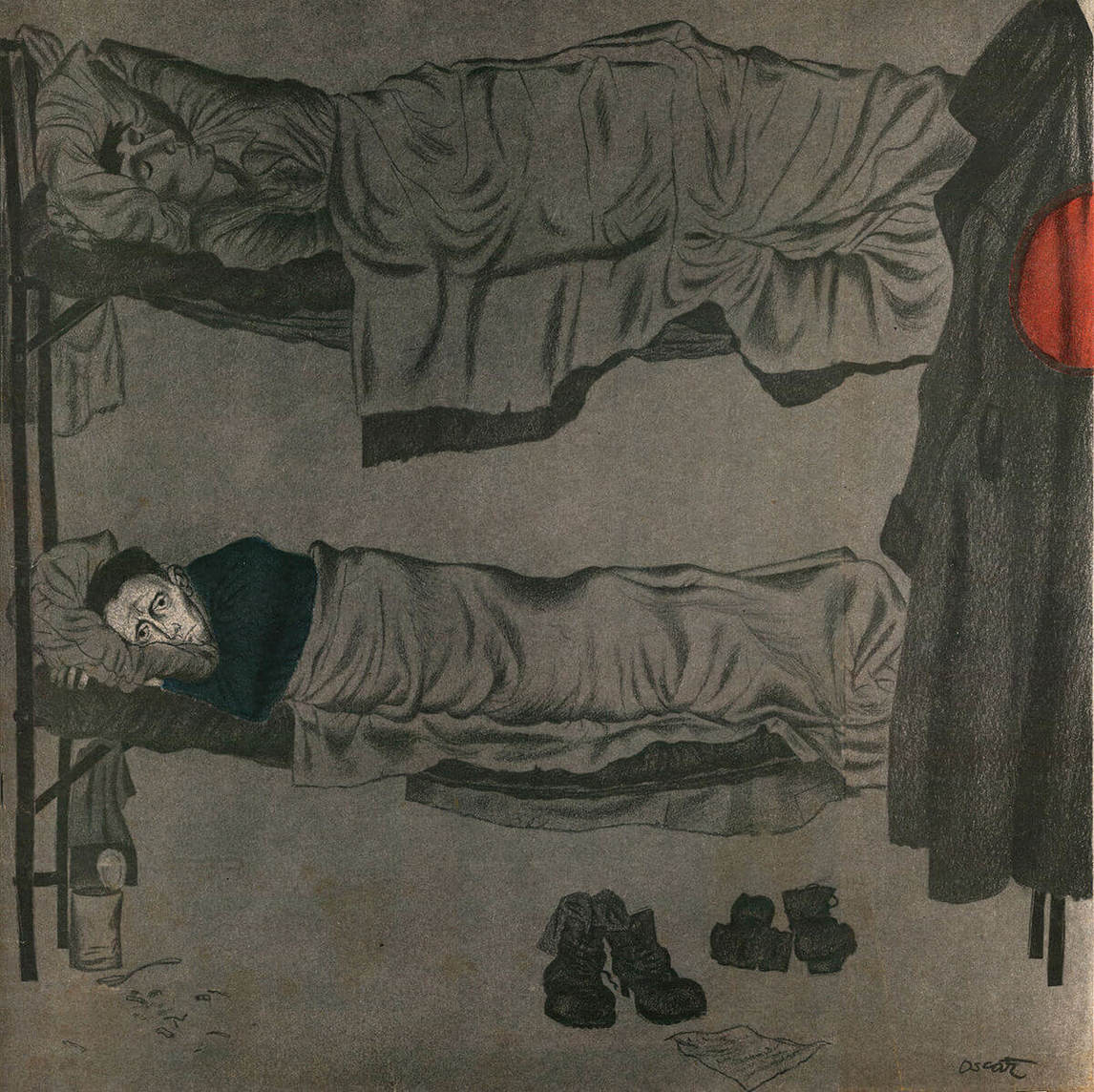

The scene is Camp N, near Sherbrooke, Quebec, where Cahén was interned for two years. Later, he equated Camp N with a Nazi prisoner of war camp in a short-story illustration; the telltale jacket with the scarlet circle identifies it as Camp N, where interns had to wear the hated red target on their backs. According to former inmates, abuse ranging from schoolyard-level anti-Semitism to rape was committed by Canadian soldiers there. But Cahén’s fellow “camp boys” remember him as cheerful, cracking jokes with a wry “Berliner” wit. These two faces—one dark and tragic, the other playful and optimistic—characterize not just Cahén’s personality, but his later artwork as well.

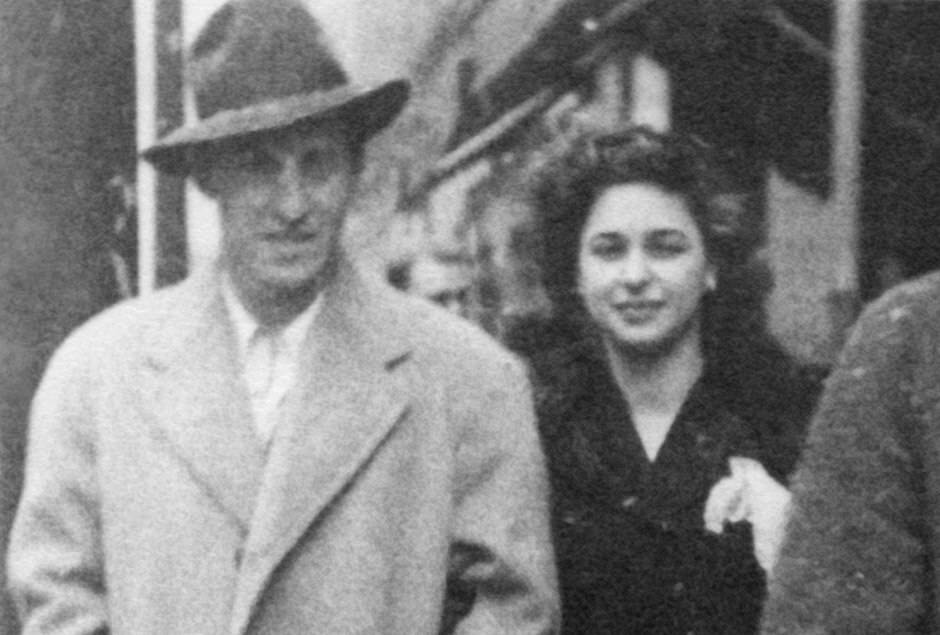

His intimate friend Beatrice Shapiro Fischer relates that she met Oscar Cahén when she—an editorial staff member of Magazine Digest in Toronto—came to interview an internee, and Cahén bribed the other men with drawings so that they would drop out of the line-up to see her. Crowded into a guard’s kiosk with no place to sit, standing eye to eye as she asked her questions, they fell in love. Cahén was “wonderfully humorous,” she remembers, but clearly suffering from stress. He was “this quivering, brilliant, agonized presence” and “his face was pain-filled . . . that pain never entirely left him.”

In 1942 a liaison with the Central Committee for Interned Refugees took his and other internees’ artwork to prospective employers in Montreal. The Standard requested drawings of a rather clichéd ski chalet scene while cautioning that “this trial is on a purely speculative basis.” Soon The Standard proudly told readers: “[Oscar Cahén’s illustrations] are so outstanding that we’ve sent him some of our coming fiction offerings. . . . Watch for his name because he is our ‘find’ in the world of commercial art.” Contrary to previous reports, the subjects Cahén illustrated were amusing and lighthearted. He loyally remained a regular illustrator for The Standard until his death.

Meanwhile Oscar and Beatrice kept up correspondence, and she moved to Montreal in order to help free the interns. Secure employment was the prerequisite for being released from Camp N, so Beatrice found jobs for herself and then for Oscar with entrepreneur Colin Gravenor, who ran a public relations firm. Oscar Cahén was released from Camp N on October 26, 1942. At Gravenor’s firm, he and Beatrice collaborated as writer and illustrator.

In November 1943 Gravenor used his influence to get Cahén into a prestigious exhibition at the Art Association of Montreal. There was no better exposure for a Montreal artist. A review noted that Cahén “works by many methods, in many styles, and with many subjects . . . there are good designs . . . neat caricatures and remarkably good and suggestive sketches of heads and figures.” Earlier the same year Cahén had joined the Montreal office of Rapid, Grip and Batten, where he was the highest paid artist, at $90 a week.

In 1943 American officials told Oscar that Fritz Max was mentally ill and required “chemical therapy,” and could be deported back to Nazi-controlled Europe. His mother, meanwhile, was stuck in England, where she now worked for the BBC. Despite these traumas, Oscar’s personal life improved.

Stability in Toronto

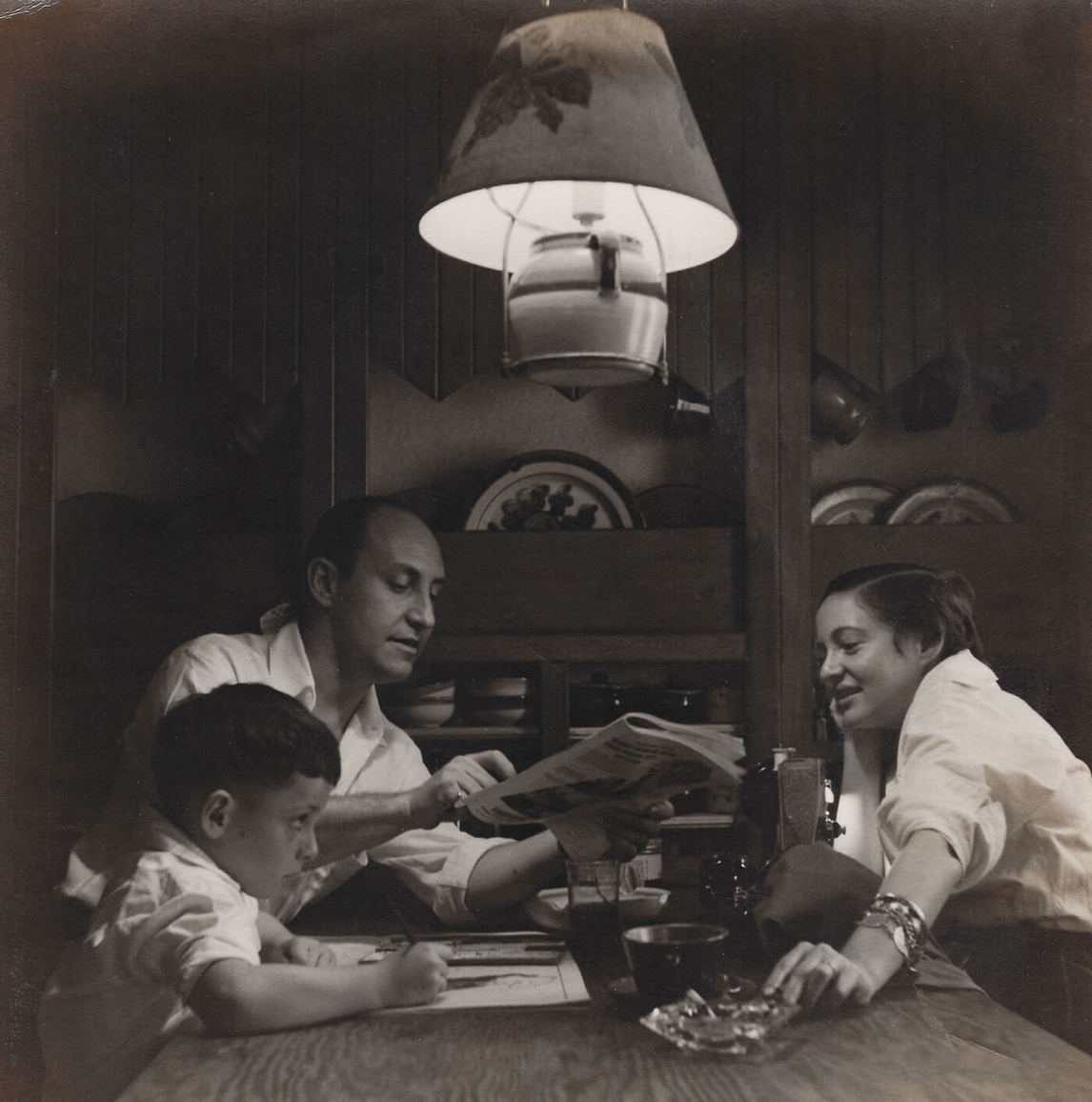

Although he retained his love for Beatrice, in 1943 Oscar met and married Martha (Mimi) Levinsky, daughter of a Polish rabbi, who had spent her childhood in the Netherlands. Sadly for Mimi, her Orthodox parents disowned her for marrying Oscar. Their only child, Michael, was born May 8, 1945; Michael—affectionately nicknamed The Noodnik and The Monster—appeared in several cover designs for Maclean’s and other magazines.

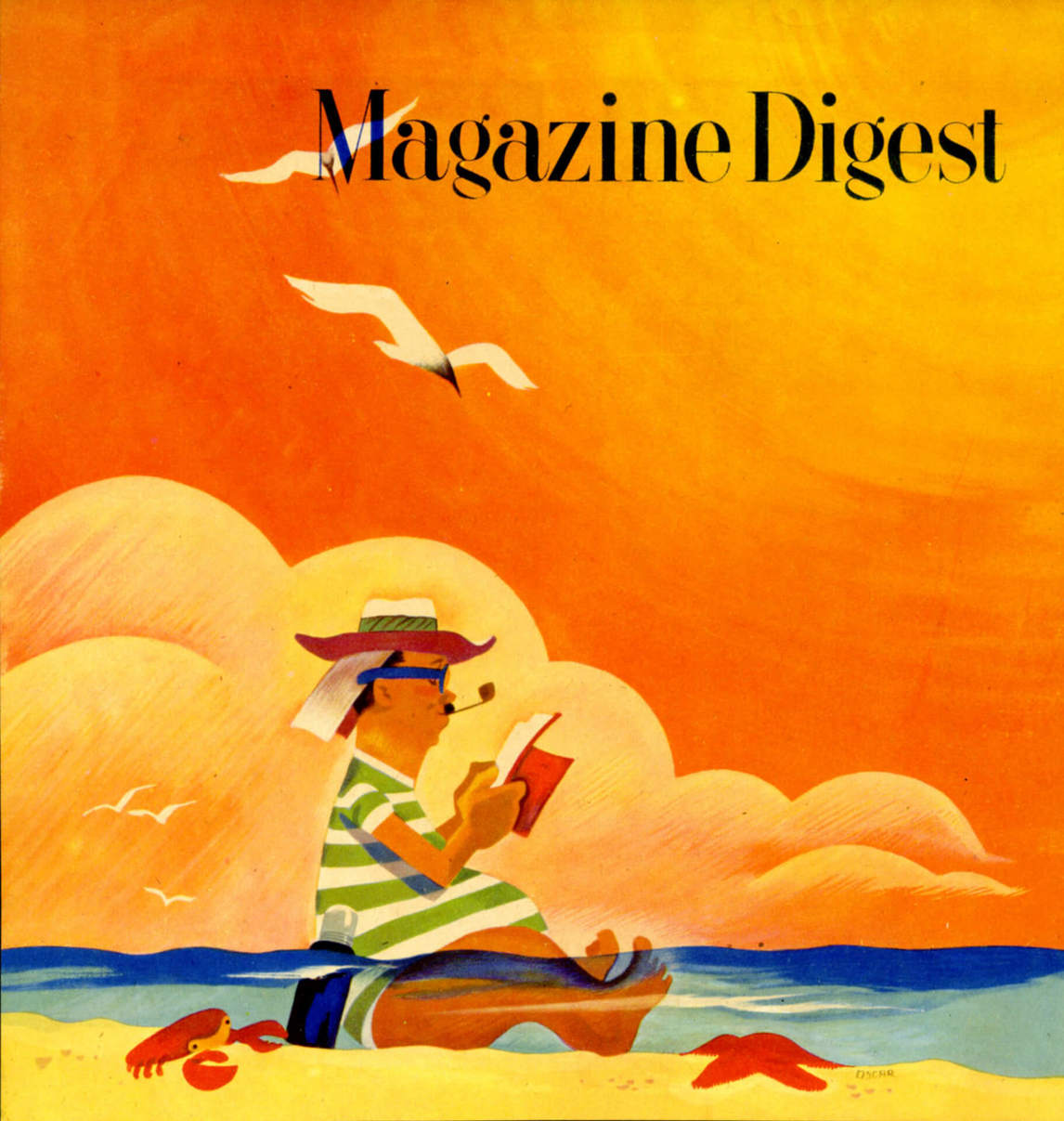

In late 1944 Oscar Cahén moved to Toronto to become art director for Magazine Digest. He introduced cheerful covers and interior cartoons and, in utter contrast, two gut-wrenching visual essays concerning impoverished Native Americans and orphaned children in Europe.

Cahén began to put down roots, building a rustic house and studio himself on Fogwood Farm near King City (just north of Toronto) in 1946. The families of illustrator Frank Fog (1915–unknown) and art director Bill Kettlewell (1914–1988) already had houses there. That same year he was granted Canadian citizenship; in June 1947 his mother arrived from England. With the stability of steady freelance income and a home of his own at last, Cahén gave up Magazine Digest and began painting for himself. It was finally safe to process the years of exile and war, and he “began to release fine frenzies in paint [that] if left pent-up torment him to the point of nervous breakdown,” as one news feature put it.

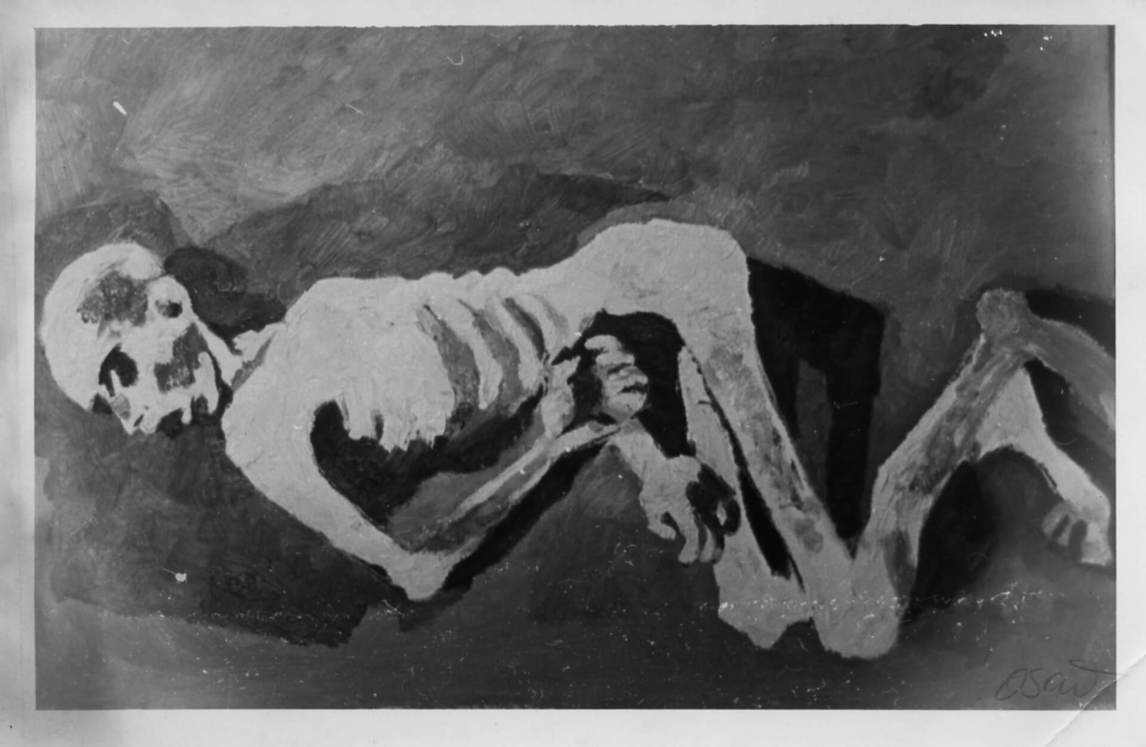

Fritz Max, still not well, was at first not permitted and was then unwilling to join his wife and son in Canada. Perhaps these painful facts informed Oscar’s images of suffering families and grief, their bodies marked with savage, heavy strokes. Paintings from this time, known only from inscribed photographs, depict an emaciated Holocaust victim and a drowned woman. During the late 1940s Cahén also produced a series of paintings and mixed-media works on Christian themes, including the largest canvas he had completed to date, the highly Cubist The Adoration, 1949.

Despite the darkness within, the charismatic Cahén hosted weekly summer gatherings, and his social circle expanded happily to include artists and designers Harold Town (1924–1990), Walter Trier (1890–1951), Albert Franck (1899–1973), and Walter Yarwood (1917–1996).

Prosperity and Prominence

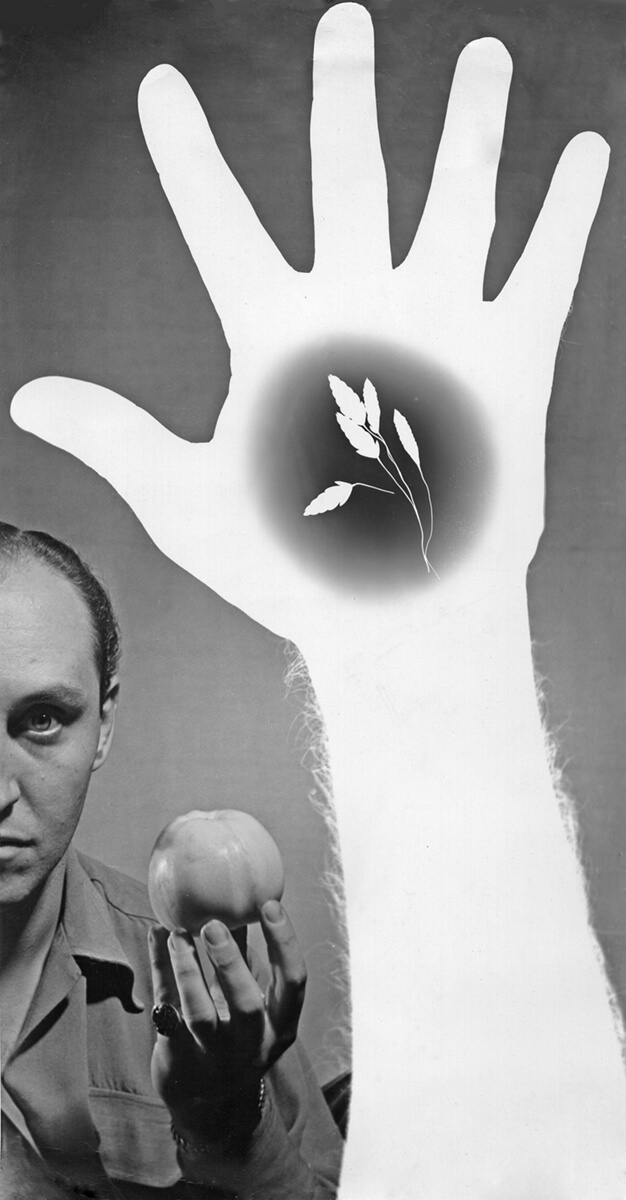

Around 1949 Cahén began exploring wholly abstract forms, establishing his personal vocabulary of crescents, spikes, ovoids, and hot, startling colour by 1952. He also explored printmaking and ceramics. His time seems to have been split fairly evenly between illustrating and painting, the former providing the financial stability and social prominence that allowed him to be as experimental as he wanted in his self-directed works.

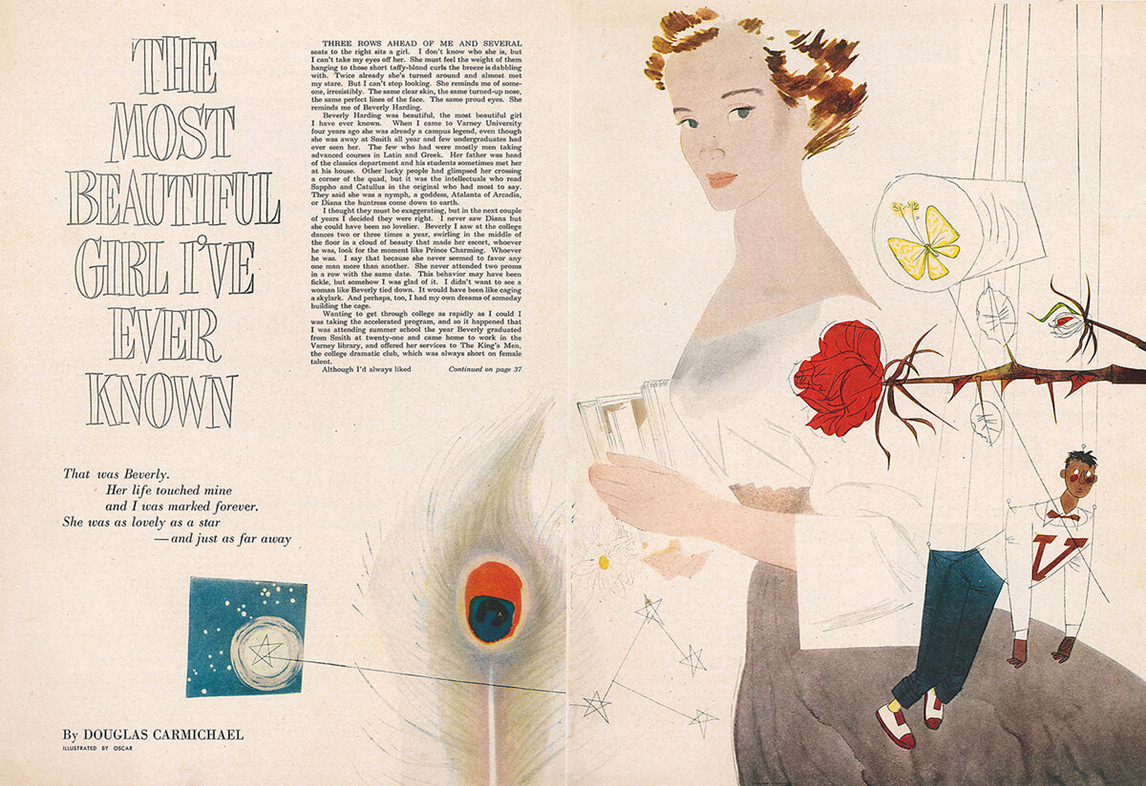

In about 1951 a New York firm purportedly was unsuccessful in their attempt to recruit Oscar Cahén with an offer of a $25,000 salary (the average U.S. income for 1950 was $3,216). Between 1950 and 1957, Canadian magazines published at least three hundred of Cahén’s illustrations. His rendering for “The Most Beautiful Girl I’ve Ever Known” won the 1952 medal for Editorial Illustration from the Art Directors Club of Toronto; it was then exhibited by the Art Directors Club of New York, alongside Norman Rockwell (1894–1978), Al Parker (1906–1985), and other American luminaries. In Canadian Art magazine Cahén said, “The trade of illustrator is often looked down upon by ‘fine artists’ which is regrettable.… Creative illustration combines fine artistic values with literary and realistic interpretations.”

He was able to purchase a sports car, and around 1952 the Cahéns began to drive to resorts near Venice and Naples in Florida each winter, where many American artists were active. Research on his time there, the connections made, the art seen, and what cities they may have visited on the long journeys back and forth has not yet been done. Near Oakville, Ontario, the Cahéns built a sophisticated new house with a large studio space and moved there in 1955. The house was a galaxy of difference from the makeshift barracks of Camp N, where Oscar had made his first Canadian illustrations.

Creatively, illustration had the advantages of access to a wide audience and licence to explore media and ideas not considered serious enough for gallery art—but the obligation to communicate in easily understood pictures precluded certain types of creative expression. Abstract painting permitted self-expression in non-literal modes—but many Canadians and fellow artists did not appreciate such art. The problem of broadening Canadians’ visual horizons was a matter of concern for avant-garde and modern artists. In 1948 expatriate painter James Imlach (untraced)—a friend of Cahén, Walter Yarwood (1917–1996), and Harold Town (1924–1990)—writing from New York, urged them “to work towards a true progressive school of art in Canada and show the world what the soil of spacious freedom can do for mankind.” In 1953 the three discussed mounting an exhibition of abstract painting only, in order to show “a unity of contemporary purpose.”

By coincidence, only weeks later, artist William Ronald (1926–1998) convinced the Simpson’s department store in Toronto to display some abstract paintings with their sleek postwar modern furniture. Cahén submitted Candy Tree, 1952–53, and Bird and Flowers, 1953. According to Town, during a publicity photo shoot of participants, Cahén brought up the group show idea, and an ensuing meeting resulted in the formation of the collective Painters Eleven to do just that. Active until 1960, Painters Eleven members were Jack Bush (1909–1997), Cahén, Hortense Gordon (1889–1961), Tom Hodgson (1924–2006), Alexandra Luke (1901–1967), Jock Macdonald (1897–1960), Ray Mead (1921–1998), Kazuo Nakamura (1926–2002), Ronald, Town, and Yarwood.

The group legitimized abstract art, inspired younger artists to follow avant-garde directions, and brought Canadian art into conversation with international contemporary art trends and critics.

The work Cahén now produced was playful, bright, and lyrical; it was also bold, dark, and aggressive, reflecting the ongoing contrasts in Cahén’s life. A growing, invigorating public profile encouraged his output: Cahén’s exhibition record between 1953 and 1956 reveals that his art was on display almost constantly, while his illustrations appeared every month.

Cahén was so well known by 1953 that he was asked to give a celebrity endorsement for a Crosley television set ad. His canvas Requiem, c. 1953 (currently unlocated) was included in the 2nd Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil, 1953–54. While success came rapidly now, dark corners remained: his father, Fritz Max Cahén, still resided in the United States, and Oscar said that he had “lost touch” with him. His wife, Mimi, doubtlessly suffering from her own family history, proved to be a difficult partner. Oscar’s strong but secret feelings for his friend Beatrice Fischer, whom he saw often, continued.

Oscar Cahén included mainly abstract works in his first solo art show (Hart House, Toronto, October 16, 1954). Yet he continued to value representational approaches: in 1956 he used a sun motif in a mural commissioned by Imperial Oil, and he completed the large canvas Warrior, 1956. Stark contrasts power the abstract work Untitled (616) of the same year: its forceful brushwork is both optimistically energetic and tersely violent.

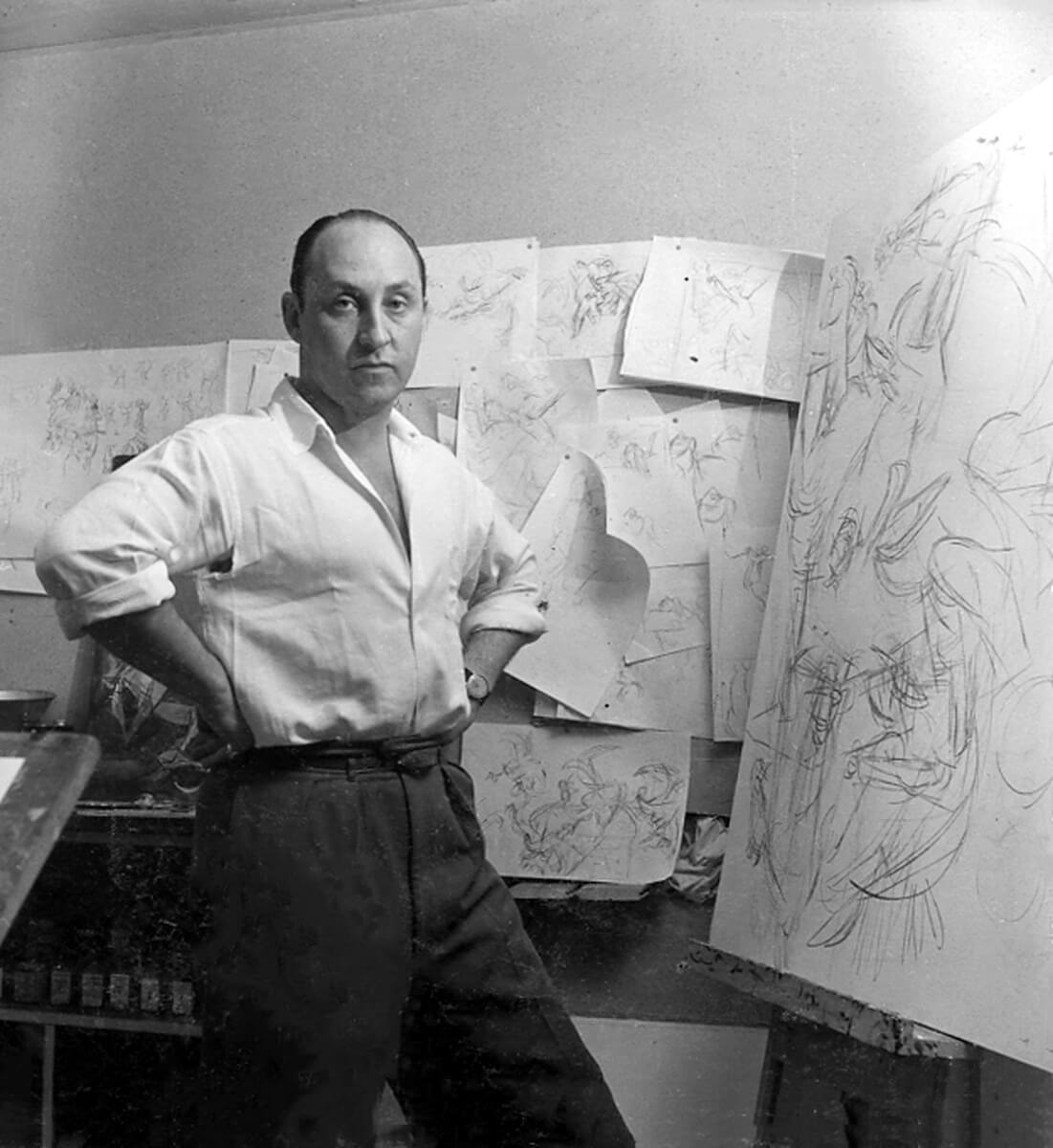

One late-autumn day in 1956, driving home in his new Studebaker Hawk, Oscar Cahén died in a collision with an oncoming dump truck. He was forty years old. There is a photograph of Oscar Cahén taken in 1951 and later inscribed on the back by his mother, Eugenie: “My beloved son Oscar Cahén shortly before his death 1956, 26 November.” The photo shows a much different Oscar than the grinning boy seen in Dresden circa 1930. This Oscar, filled with memories of disenfranchisement, flight, internment, and rebirth in a strange country, does not smile: he stands erect with fists on hips before his easel and numerous drawings, staring boldly, defiantly, into the lens, serious about his work.

In the aftermath of Cahén’s death, Harold Town and Walter Yarwood arranged a memorial exhibition held at the Art Gallery of Toronto in March 1959, and other retrospectives have followed over the years. Nevertheless, Cahén’s legacy was diminished by the lingering after-effects of wartime trauma: Eugenie left to rejoin Fritz Max, who had returned to Germany in 1954; and Mimi, suffering from depression, could not manage the estate well alone. As a result, most of Cahén’s drawings and paintings lay unknown in storage for over forty years. Happily, when his son, Michael Cahén, inherited the collection, he began making it and related papers accessible, and scholars are re-evaluating Oscar Cahén’s contribution to Canadian art.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements