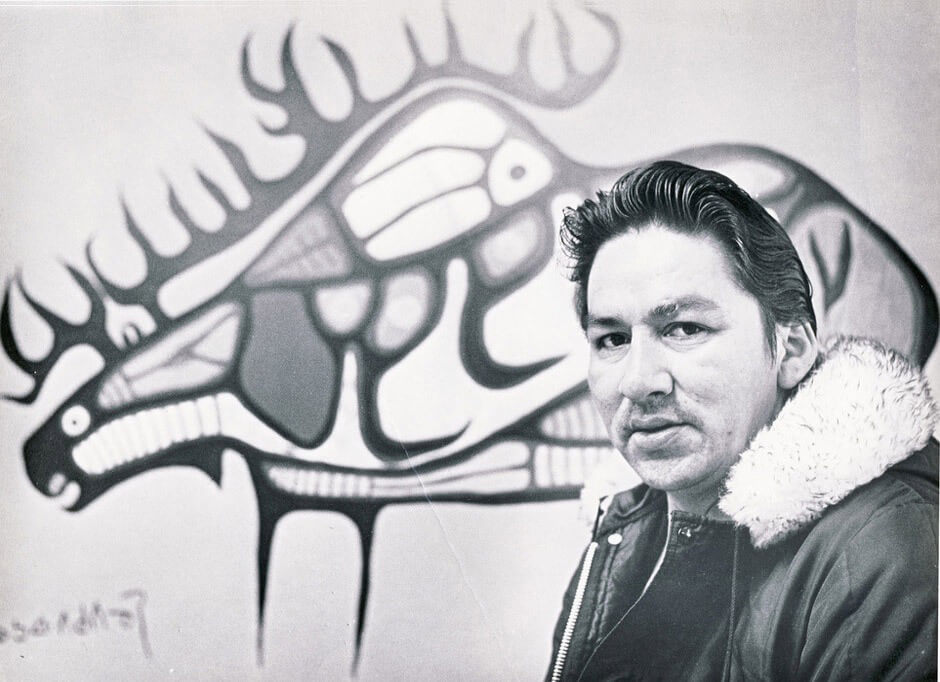

At a time when most Canadian artists were experimenting with the techniques of modern abstraction, Norval Morrisseau rejected those contemporary artistic trends in favour of a visual aesthetic that drew most directly from Anishinaabe cultural sources. In doing so, he created a style that was all his own.

Early Experiments with Cultural References

When he began to create art in the late 1950s, Norval Morrisseau perused books supplied to him by his artist friends Joseph and Esther Weinstein and Selwyn Dewdney (1909–1979) for additional direction. He was enthralled by colour reproductions of work by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Henri Matisse (1869–1954), studied examples of Mayan art, and inspected the forms and themes in Northwest Coast carvings. Primarily, however, Morrisseau tapped Anishinaabe spiritual teachings and art as inspiration for his style. Curator David W. Penney sums up the result:

Morrisseau’s great insight, visible to us without the benefit of esoteric teaching, is the transitive and relational nature of all things. In his monumental paintings, his figures inhabit worlds in which they are inextricably immersed in states of transmission and transformation. He shows us an Anishinaabe vision of place that cannot be separated from the beings, human and nonhuman, material and immaterial, of which it is part, a place that is enacted rather than occupied.

It is Morrisseau’s holistic and interconnected sense of the world that offers an entry point for understanding his artistic style.

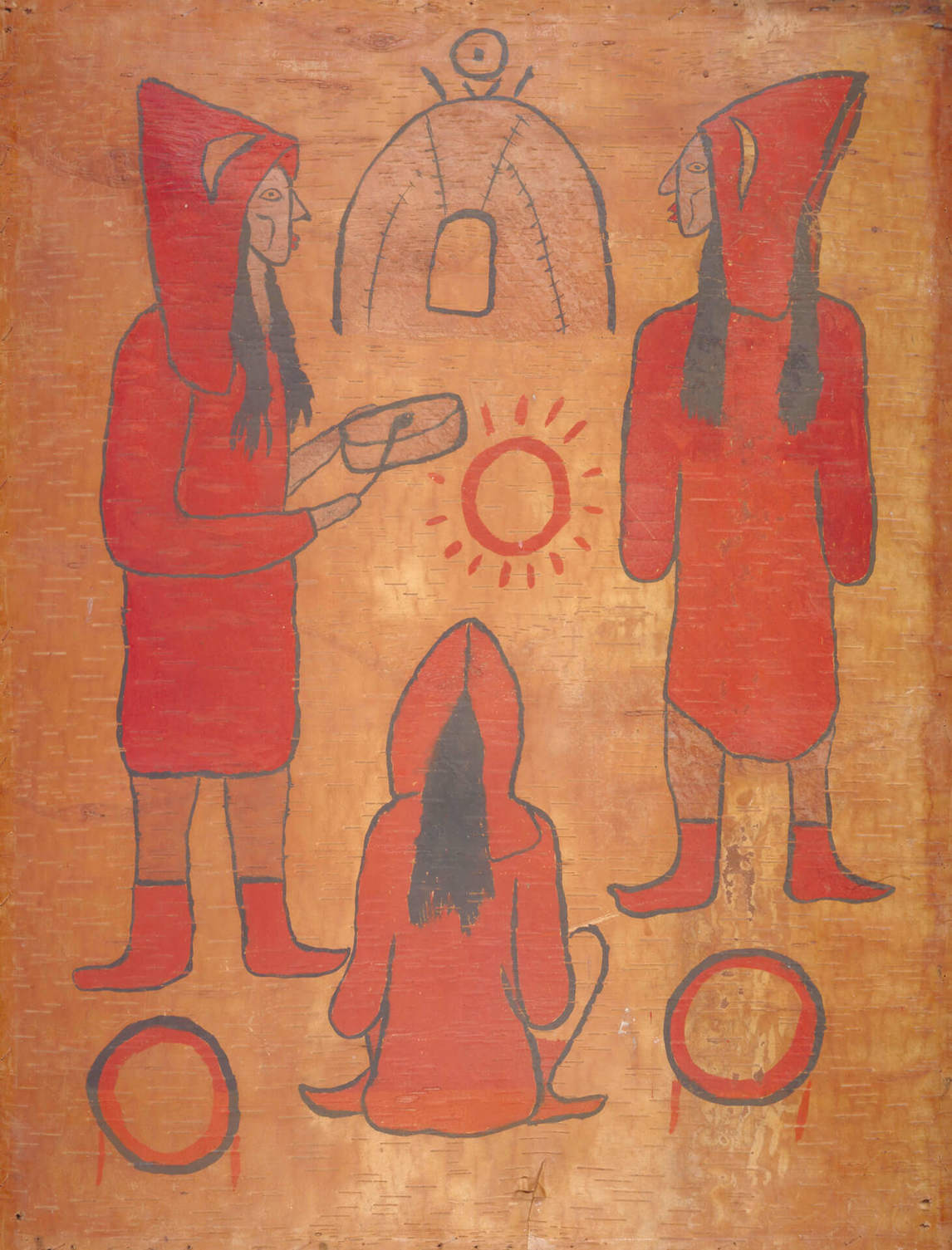

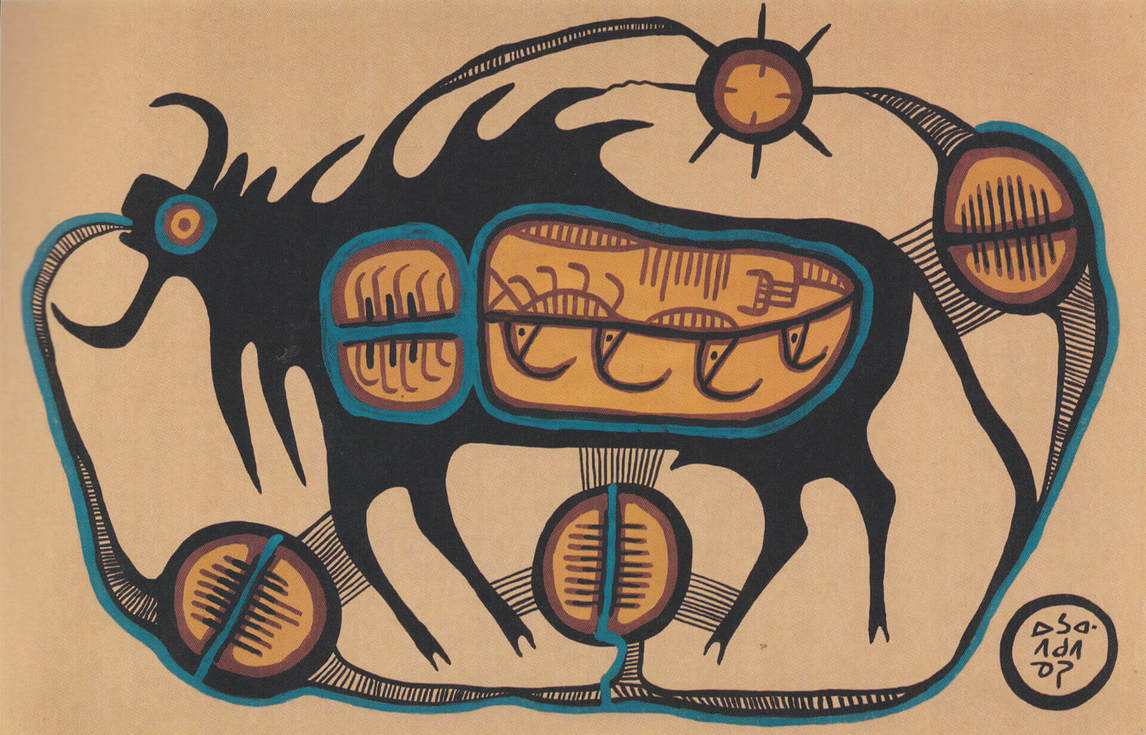

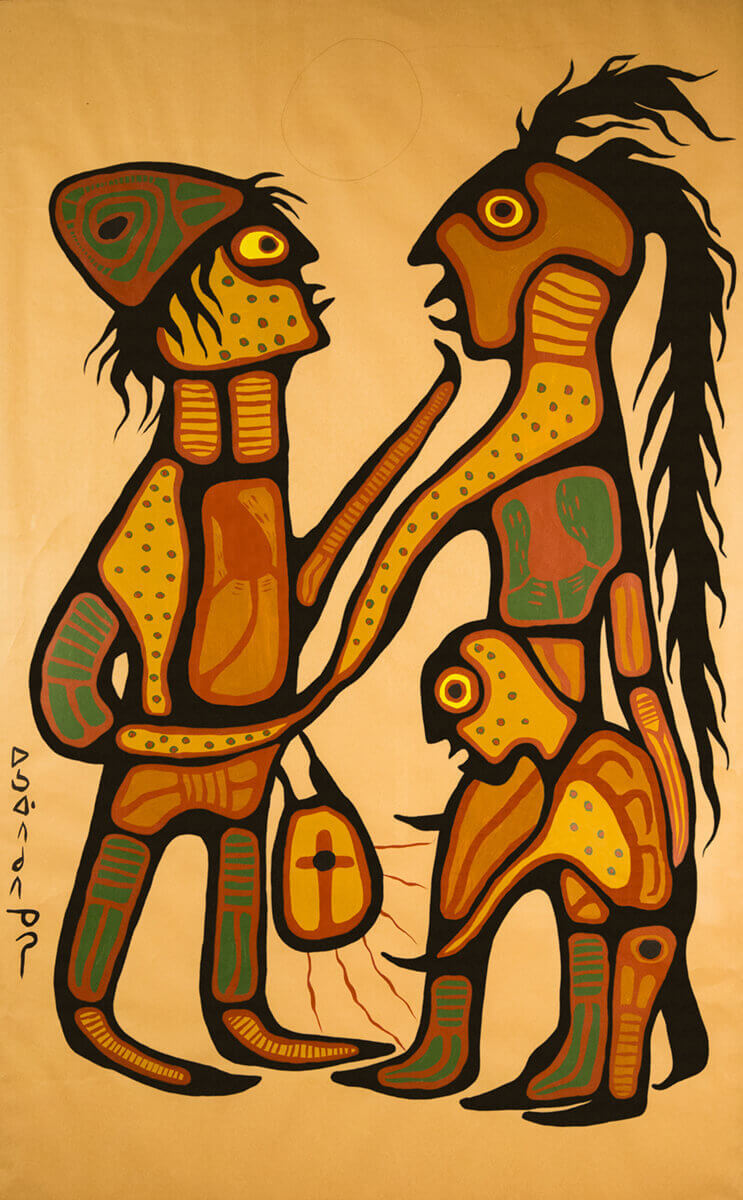

Morrisseau’s early works of the 1960s, including Ancestors Performing the Ritual of the Shaking Tent, c. 1958–61, demonstrate his close connection to generations of Anishinaabe elders. Works such as Ancestors Performing the Ritual of the Shaking Tent, which were made on birchbark and in earth tones, deliberately reference stories and imagery from traditional Anishinaabe culture, such as rock art and the sacred Midewiwin medicine scrolls. For example, the pictograph of Micipijiu at the Agawa art site in northwestern Ontario is similar in form to Morrisseau’s Water Spirit, 1972. Yet while these images share a common subject and arrangement, Morrisseau used formal elements such as composition, colour, and line to direct his art in fresh, innovative ways.

Composition

Throughout his career, Norval Morrisseau repeatedly used the same classic, balanced compositional forms, as exemplified in Untitled (Two Bull Moose), 1965. As well, he often situated his subjects in a pyramid with a central image or in a symmetrical arrangement with two figures or groupings balanced on the ground of the work. Untitled (Thunderbird Transformation), c. 1958–60, is an early example that demonstrates this proportioned structure. Morrisseau positions the two figures opposite each other to achieve balance and uses three circles—suns or divided circles—to frame their heads. Created more than twenty years later, Androgyny, 1983, shows the dominating Thunderbird anchoring a symmetrical arrangement of figures on either side of two central ovoid forms. However, it is Morrisseau’s portraits, from all periods, that best show the artist’s preference for a stable central composition with a clear focal point. Indian Jesus Christ, 1974, and Artist in Union with Mother Earth, 1972, illustrate this style.

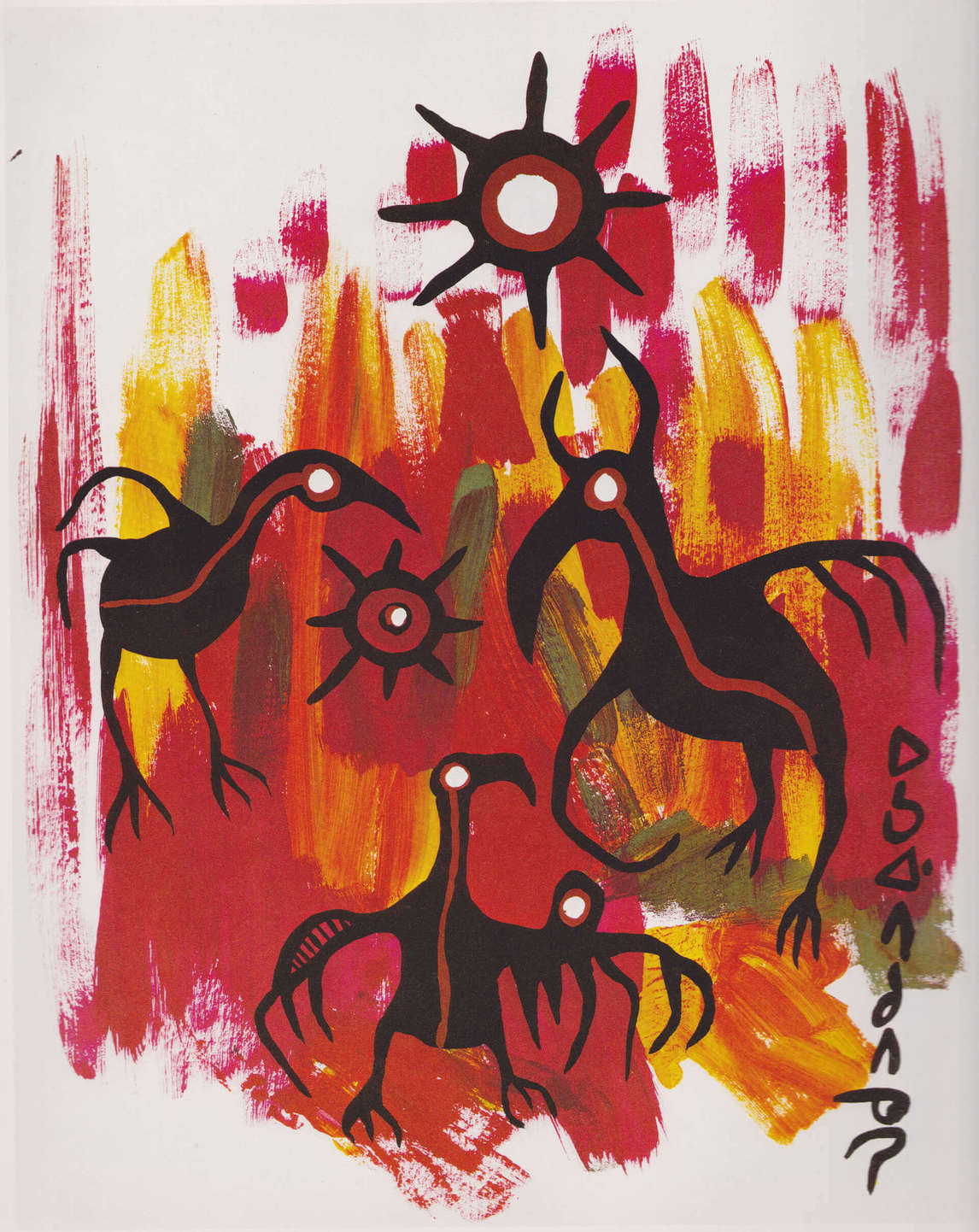

While he returned to this symmetrical structure many times, Morrisseau was an innovator and was not complacent with regard to style or technique. He often experimented: Impressionist Thunderbirds, 1975, for example, maintains the prominent central focal point, but the abstract, painterly background dramatically illustrates Morrisseau’s awareness of European modern styles such as Impressionism. This painting clearly shows Morrisseau’s willingness to explore more ways to render his Thunderbird imagery.

Colour

Many of Norval Morrisseau’s first works from the mid- to late 1950s were line drawings on birchbark, such as Untitled (Thunderbird Transformation), c. 1958–60. He experimented first with coloured pencils and then with oil paints, but in the early 1960s he began to rely on acrylic paints. Unlike many other artists, he seldom mixed colours, preferring instead to apply pigment directly from the paint tube. In addition to using a variety of brushes, Morrisseau often added liberal daubs of pigment to small sections of a painting using his fingers, which created a thick, uneven impasto, or layer of paint, on the canvas.

While he is acknowledged as a bold colourist, Morrisseau varied his palette, especially in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when he used earth tones to relate some works to tanned hides, birchbark, and other natural elements of his Anishinaabe roots. Yet even when Morrisseau was working with a limited palette, as in Migration, 1973, he was thinking about the colours’ significance to the overall painting. In its use of green and red, The Gift, 1975, symbolically communicates a juxtaposition between the beliefs of the missionary and the shaman; even without bold colouring, the intense rendering of the eyes in that painting and many others makes them focal points and symbols of varying states of spiritual significance. Morrisseau said of the process of painting, “The colours are in my mind somewhere. In fact, I have no preconceived idea where they will go. I can almost see them clearly.”

The artist’s use of colour became bolder and brighter in his later paintings of the 1970s, especially after he discovered Eckankar. Morrisseau explained, “We can learn how to heal people with colour.… My art reminds a lot of people of what they are.… Many times people tell me that I’ve cured them of something, whatever’s ailing them.… It was the colour of the painting that did that.” Works including Shaman and Disciples, 1979, Man Changing into Thunderbird, 1977, Androgyny, 1983, and Observations of the Astral World, c. 1994, show the copper, yellow, and turquoise pigments that became Morrisseau’s signature colours and conveyed the clarity of vision, lightness, and spirituality that Eckankar espouses.

Lines

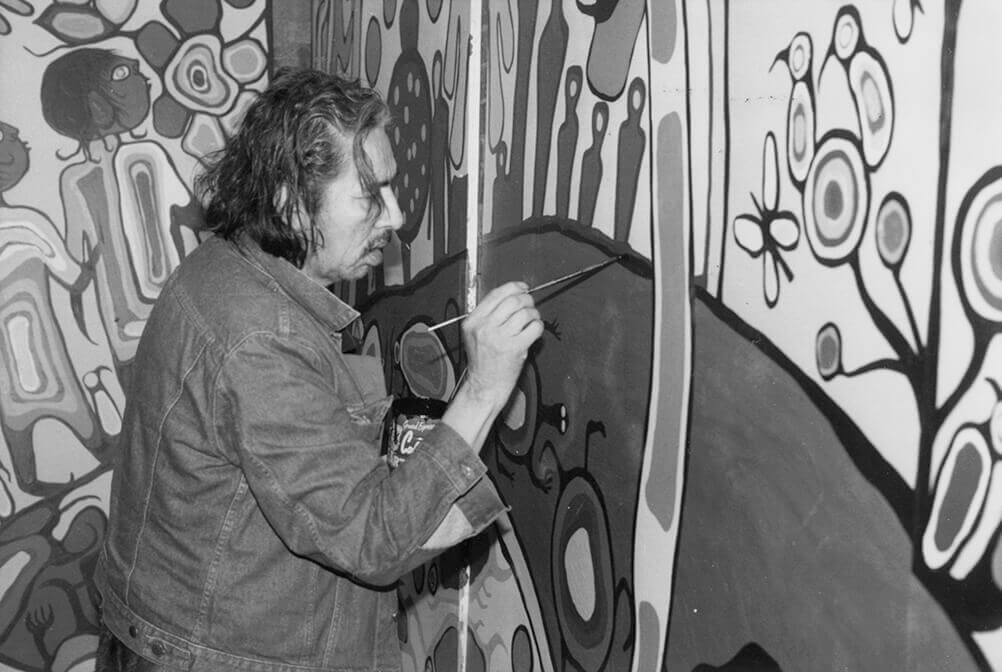

Norval Morrisseau tended to paint quickly and intuitively, and is not known for draftsman-like precision. As is evident in a photograph of the artist painting Androgyny, 1983, his expressionistic strokes are uneven and large patches of background colour appear blotchy. Yet Morrisseau’s defining black outlines unite all aspects of the work, providing an overall assuredness to his art.

These lines perform a number of functions. In many of Morrisseau’s paintings there are “lines of communication” that “join animals and people in structured associations. They mark relationships, often forming closed loops, almost resembling electric circuits. Morrisseau uses them often because the foreground concept, the real subject of his pictures, is usually his own perception of the quality of interdependence.” In other words, these lines, which are sometimes referred to as power lines, connect the figures to one another to create a balanced composition of interrelated figures.

Another common form, created by these black lines, is the divided circle. Morrisseau included this form in his earliest works from the late 1950s, and it exists throughout his oeuvre, as in Sacred Buffalo, c. 1963, representing “all the dualities which are present in the artist’s view of the world—good and evil, day and night, heaven and earth, and so on.” Elizabeth McLuhan explains that Selwyn Dewdney traced this form to the megis, or cowrie shell, that is an important part of the Midewiwin medicine bag and a source of power for shamans. In a letter written to artist Susan Ross, Morrisseau specifically referred to the divided circles as “my favorite art sign” and drew a small diagram with the word “good” on the left and the word “bad” on the right of a bisected circle. Each of the seven circles included in Water Spirit, 1972, is rendered in two colours beyond the requisite black outline. Additionally, Morrisseau painted a black dot in each side of each circle to accentuate the notion of symbolic balance. By linking the line and the circles, he visually reinforces a holistic understanding. This clear relationship between the lines of communication and the divided circle has become a convention adopted by other artists who paint in the style of the Woodland School.

In Morrisseau’s work of the 1980s and 1990s, such as Observations of the Astral World, c. 1994, the divided circles sometimes give way to other groupings. In this painting, different astral planes (land, water, spirit realm) are pictured within ovals of different colours. However, the realms remain interconnected by a central tree whose branches link the outstretched arms of the child and the shaman.

In addition to the divided circle, Morrisseau used lines to segment the inner structures of many animals and humans. While some of these interior spaces contain well-defined elements such as the womb, the heart, and the backbone, others show more decorative elements, such as the “latticework” design Morrisseau adapted from Midewiwin birchbark scrolls and refined for his own art. This use of interior segmentation to convey meaning is visible in The Gift, 1975. In Man Changing into Thunderbird, 1977, Thunderbird with Inner Spirit, c. 1978, and The Storyteller: The Artist and His Grandfather, 1978, Morrisseau uses interior space to add layers of rich, complementary colour patterns. The result in Man Changing into Thunderbird is almost baroque: the ornate colour patterns pulsate, resulting in a transformative dynamic.

A Call for Change

Norval Morrisseau’s art had a strong activist and educative function. Like the Futurists in Italy or the Constructivists in Bolshevik Russia, Morrisseau pioneered a new style as a call for change. He was an Indigenous man living in an oppressive, assimilationist environment that saw Indigenous artistic expressions as souvenirs or crafts rather than as fine arts. Though Morrisseau’s style and technique evolved over the course of his career—from early Anishinaabe-inspired works through more Christian themes to canvases that fuse his spiritual study of Eckankar with his Indigenous roots—his works often had a political dimension. Works including The Gift, 1975, drew attention to the inequality resulting from Canada’s colonial relationship with First Nations and, in their blending of the traditional and the contemporary, they confounded expectations and easy analysis and challenged conventional thinking about Indigenous peoples.

Morrisseau’s success on the Canadian art scene has inspired other Indigenous artists to follow. He facilitated educational workshops in remote communities in Ontario, in which he encouraged Indigenous youth to conceptualize themselves as artists and paint their own stories using the formal elements of his visual vocabulary. Daphne Odjig (b. 1912), Jackson Beardy (1944–1984), Blake Debassige (b. 1956), Carl Ray (1943–1978), Joshim Kakegamic (1952–1993), and Benjamin Chee Chee (1944–1977) have all studied Morrisseau’s style as they have developed their own approaches to art making. Morrisseau’s sustained use of visual narratives and cultural approaches in his painting demonstrates that he was also committed to “addressing the vacuum created by the systemic efforts of successive governments to neutralize any Indigenous cultural expression reminiscent of the old days.” Most importantly, however, Morrisseau continued to use his painting to advocate for change, giving voice and artistic direction to new generations of viewers and artists who encounter this art.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements