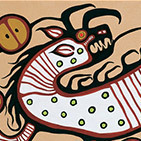

Self-Portrait Devoured by Demons 1964

Norval Morrisseau, Self-Portrait Devoured by Demons, 1964

Acrylic on paper, 209.2 x 78.7 cm

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Norval Morrisseau painted this work two years after his gallery debut at the Pollock Gallery in Toronto. He made a number of self-representations over the course of his career and Self-Portrait Devoured by Demons is an early but powerful example of this aspect of Morrisseau’s oeuvre. He painted two other versions of himself entwined with snakes; together, these works signify the struggles Morrisseau faced upon entry into the mainstream art world.

In this painting, seven snakes envelop the artist. A Freudian interpretation would read the snakes as phallic symbols. In Christian tradition, snakes are associated with evil. Yet given Morrisseau’s cultural background, an intersection of meanings is central to understanding this imagery. In Anishinaabe culture, the snake is not always a signifier of evil: as early twentieth-century ethnomusicologist Frances Densmore noted in her field research of the Anishinaabe, snakes also have powers to heal the sick and were used in mide rites of the Midewiwin religion.

The number seven, too, is significant. In Christianity, it signifies spiritual perfection and completeness. As Anishinaabe scholar Edward Benton-Banai points out, this number is highly emblematic for the Anishinaabe: seven fires, seven original clans, and seven generations. Seven also denotes spirituality, completeness, and redemption. Benton-Banai explains that the seventh fire, for example, is a prophetic rebirth and renewal of Anishinaabe culture. Morrisseau also used seven as a signifier in his painting Water Spirit, 1972. In this painting, he surrounds Micipijiu, the horned water lynx, with seven divided circles to reinforce the supernatural power of the spirit-being.

In Self-Portrait Devoured by Demons, Morrisseau appears to be bound by the snakes, which may suggest the uncertainty he felt as an emerging contemporary artist. Although these snakes recall traditional stories, Morrisseau may have reinterpreted their meaning to suit his contemporary situation. The snakes may be read as a visual reference to the stranglehold Morrisseau’s Indigeneity (both cultural and political) had on him as an artist and as an Indigenous man living in Canada in the 1960s. As he broke new ground, tentatively negotiating the terrain of Canadian cultural politics, Morrisseau was clearly uncertain of his fate and he renders that sense of vulnerability here.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements