During her long and illustrious career, Molly Lamb Bobak worked primarily in oil or watercolour, but also produced drawings, prints, and illustrations. Most of her artwork presents recognizable subject matter, but her depictions of crowd scenes, still-life compositions (including flowers), and interiors reveal her interest in the formal qualities of painting—line, space, perspective, and the terrain between representation and abstraction. Although influenced by other modernist artists in Canada and abroad, she developed a style distinctively her own.

Form and Representation

In all her work, whether drawings, paintings, or prints, Molly Lamb Bobak combined representation of the scene before her with close attention to the formal qualities of artmaking— colour, brushwork, texture, line, and composition. This determination to portray daily life using highly professional techniques led her to produce a unique body of work in Canadian art. To achieve her signature style, Lamb Bobak challenged herself by pushing these formal qualities of painting in different directions. Her drawings, illustrated diaries, oil paintings, and particularly her watercolours are all created by a confident hand.

The idea that a painting must succeed as an arrangement of elements before it can succeed as a representation of something else is a central tenet of modernist art, according to critics Roger Fry (1866–1934), Clive Bell (1881–1964), Herbert Read (1893–1968), Walter Abell (1897–1956), and Clement Greenberg (1909–1994). As the post-Impressionist painter Maurice Denis (1870–1943) explained in a manifesto in 1890, “Remember that a picture, before it is a picture of a battle horse, a nude woman, or some story, is essentially a flat surface covered in colours arranged in a certain order.”

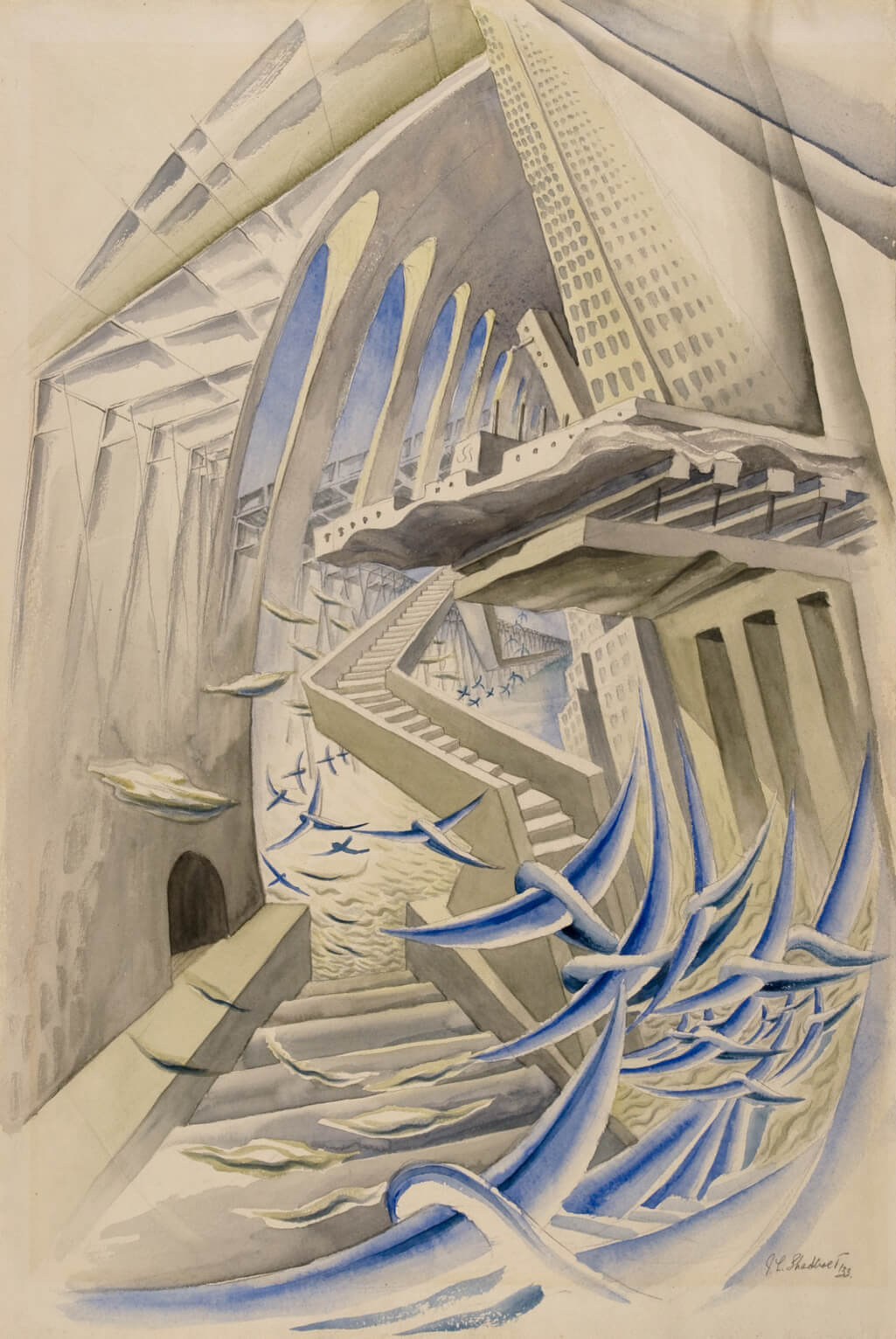

Lamb Bobak was keenly aware of art theory and how it applied to her work. Her father, Harold Mortimer-Lamb (1872–1970), had discussed Fry’s writings in particular with visitors to their home well before she began her official art education. At the Vancouver School of Art she was again exposed to these aesthetic trends when she studied with Jack Shadbolt (1909–1998), with whom she remained in dialogue until his death. Although her style was markedly different from his and she never fully embraced abstraction, he had a significant influence on her work. He guided her toward key concerns in modernist painting first by introducing her to the work of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) and, in the 1950s, by encouraging her to explore compositional elements such as line, tone, and colour.

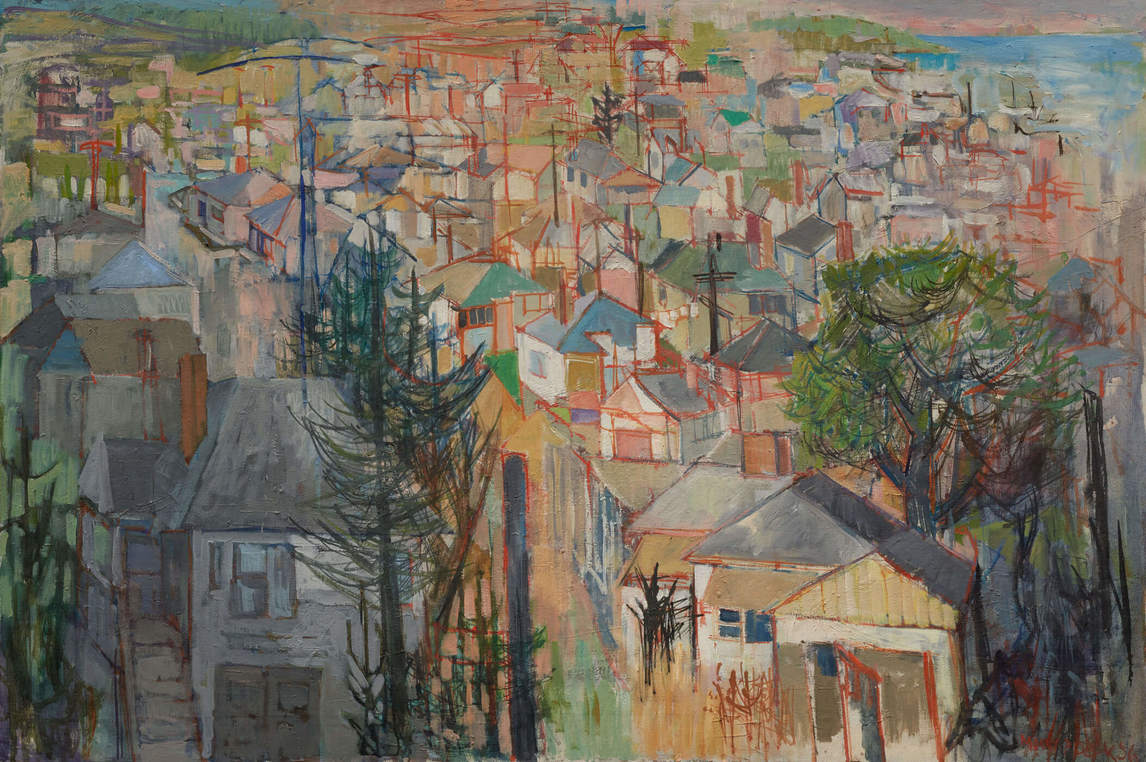

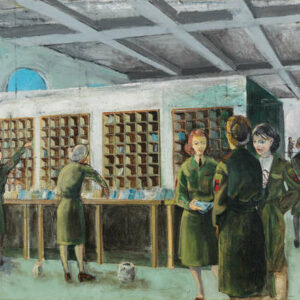

When Lamb Bobak returned to live in Vancouver following the Second World War and felt frustrated because her art had not advanced beyond the observational work she had produced as a war artist, Shadbolt advised her to focus on formal qualities—to open the way toward abstraction. In A Bakeshop, Saint-Léonard, 1951, she emphasized such values to the point where the image, though primarily a study of lines and shapes, is still recognizably the shelves in a corner of a bakery. In New Housing Project, 1956, Lamb Bobak treats line and composition in a manner similar to Cézanne in his Gardanne, 1885–86. Her paintings from this period come closest to abstraction, though she never abandoned representation.

Even when abstraction and conceptual art took hold throughout much of the Canadian and international art worlds, Lamb Bobak kept working in her customary figurative style. Over the years she took risks to advance her technique, particularly in her experiments with different perspectives in her crowd scenes (Rink Theme—Skaters, 1969, and John, Dick, and the Queen, 1977). On a few occasions, she veered toward abstraction—for example, in Black Rocks, Caesaria, 1985—but her subject matter was always recognizable. On one occasion she acknowledged that, except in her book illustrations, she had suppressed her natural impulses toward narrative because some local commentators found the “literal quality” in her work “obnoxious”; they had dismissed her tea-party images for “telling a story” about people. She succeeded in developing her own distinctive style combining representation with sophisticated and evolving technique.

A Painter of Modern Life

With her subject matter, Molly Lamb Bobak’s choices align with the ideas of the French poet and critic Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), who, in 1863, argued that modernity, in contrast to classical ideals, required an artist be a “man [sic] of the world, man of the crowd”—a painter of modern life. Lamb Bobak described how, as a young mother in Oslo, she sketched from the back of a car to capture the mood of people streaming through a city square. Later, she worked some of these quick drawings into finished paintings in the studio—as in Oslo Street, 1961.

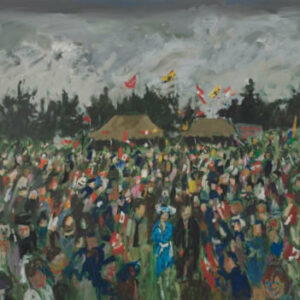

Similarly, her sketches of the 1976 official visit of Queen Elizabeth II to New Brunswick prove that she still jotted down impressions of fleeting moments in her sketchbook (see John, Dick, and the Queen, 1977). These charcoal or ink drawings, complete with colour notes, served as an aide memoire for the fifty works she produced in her studio the following year.

All her scenes capture a moment from some lived, communal experience—crowds skating (Rink Theme—Skaters, 1969), dancing (The Legislative Ball, 1986), strolling on the beach (British Columbia Beach, 1993), filling public squares, or attending convocations. They achieve a careful balance of form, colour, and space, creating a clear, rationalized vision of moving scenes that are intentionally devoid of narrative.

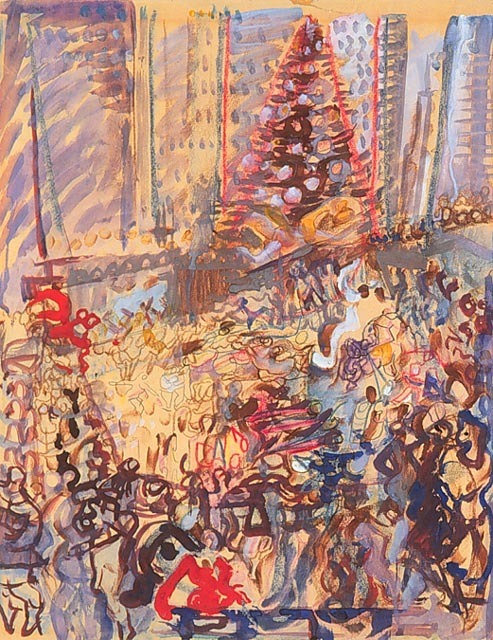

Lamb Bobak’s style may have been influenced by Pegi Nicol MacLeod (1904–1949), whom she met during the war years. Nicol MacLeod’s Manhattan Cycle, 1947–49, painted near her New York City apartment on East 88th Street, also features a colourful rush of people. Although both women shared an interest in subject matter, they differed in their treatment: Nicol MacLeod’s Christmas Tree and Skaters, Rockefeller Plaza, 1946, fills the frame with figures painted in twisting, dramatic strokes, while the crowd of figures in Lamb Bobak’s March to University, n.d., is specific and ordered as the scene unravels around it. Lamb Bobak herself did not see a close relationship in their art, though she appreciated Nicol MacLeod’s work. She described her colleague as “an outward, swirling kind of painter” whose work was “wilder . . . less controlled” than her own.

Lamb Bobak’s crowd paintings were highly sought after during her lifetime, but she struggled to identify their appeal. She thought these compositions were somehow less substantive than her other work: “There is nothing threatening in my subject matter. Sometimes, I worry if I have anything to say, truly, because I just see something and I paint it, without thinking beyond the visual thing, the movement of the people and the colour and so on. And I have to work hard to get that.” Despite her reservations, Lamb Bobak had achieved the goal Baudelaire had set for artists in pursuing the idea of modernity: to capture the “ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent half of art.” This working method was rapidly taken up by most of the Impressionist painters—Claude Monet (1840–1926) and James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) in particular. In mastering these same techniques, Lamb Bobak developed the skills needed to gauge, understand, and appreciate the whole big scene and to comprehend what it is to be modern.

Colour, Texture, and Space

Throughout her career, Molly Lamb Bobak continued to be drawn to the work of European modernists. Despite the stylistic continuity evident in her oeuvre, she was open to multiple influences in her handling of colour and texture—to Paul Cézanne, J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851), and Gustav Klimt (1862–1918). On the Beach, 1959, for example, is evocative of Klimt’s The Kiss, 1907–8. Her evolution as a painter coincided with multiple grant-supported trips she and her husband, Bruno Bobak (1923–2012), took to Europe from the 1950s to the 1970s, where they sketched and painted en plein air in Spain, France, Norway, and England. Her Black Rocks, Caesaria, 1985, bears some resemblance to Turner’s seascapes in its dramatic play of sea and sky. Warm Pub, n.d., produced likely after an extended stay in Europe, shows the influence of Édouard Manet (1832–1883) in the handling and fluidity of paint. Warm Pub recalls Manet’s famous canvas A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882. In her rendering of the pub, Lamb Bobak appears to emulate and further abstract the brushwork of Manet, and in so doing reveals the nature of painting itself: a flat surface covered in colours arranged in a certain order. A further parallel can be drawn between Manet’s barmaid and Lamb Bobak’s Private Roy, Canadian Women’s Army Corps, 1946. Both women share a forlorn quality that is achieved by their respective gazes, which do not engage the viewer in either instance. Charmaine A. Nelson cites Lamb Bobak’s sensitive portrait of the introspective Private Roy for successfully capturing an acute sense of alienation that a black woman must have felt while serving in the predominantly white CWAC.

Building on these influences, Lamb Bobak developed a style and technique all her own. The subdued palette and geometric, almost cubist compositions she painted in Vancouver in the 1950s (A Bakeshop, Saint-Léonard, 1951) gave way to the free brushwork and instinctive use of colour of her later style. Her landscapes, still lifes, and interiors from the 1960s onward employed looser compositional structures featuring a sharp freshness of colour. Corsini Palace, Florence, 1983, and Interior with Moroccan Carpet, 1993, two later interiors painted in oil, present a daring purity of colour.

These interior compositions, like her crowd scenes and flower images—for example, the gesturally rendered “Red Poppies,” 1977—are characterized by rational form, sensual detail, and unworked, exuberant colour. As she said about her watercolour Cosmos, 1977, included in Wild Flowers of Canada (1978): “I love to paint them. In the fall, I race against the first killing frost to put down all they suggest to me. I have an old brush with a few hairs left in it which helps me say something about the elegance of these crisp-growing fronds.”

Other Media

While Molly Lamb Bobak considered herself to be primarily a painter and was portrayed in the art press as such, she experimented in other media at different points in her career. In addition to her illustrated diaries and watercolours like Cosmos, 1977, she produced a small selection of prints and illustrated books by other writers.

The majority of Lamb Bobak’s paintings are in oil, but she used watercolour where she thought a more delicate and transparent treatment would be preferable. Watercolour painting had peaked in popularity during the nineteenth century, but some modernist artists continued to experiment with it for sketching and for independent works. David Milne (1881–1953) was one of them—an artist Lamb Bobak admitted had influenced her work. Initially she used watercolour pigments to add colour to sketches and drawings, but she credited her husband, Bruno Bobak, with encouraging her to explore this medium more thoroughly.

She came to value the immediacy offered by watercolour, in contrast to the rethinking and correction allowed by oil. As David P. Silcox notes in his foreword to Wild Flowers of Canada:

The paintings are at once meticulous and spontaneous. They have a consuming vitality which their delicacy does not diminish. They have a balance which their seeming disorder does not destroy. They have an immediacy of vision which is constantly renewed with each viewing. They are an act of love.

In a televised interview for the CBC in 1993, Lamb Bobak described her preference for rendering flowers in watercolour as a way to capture the natural movement of the delicate blossoms.

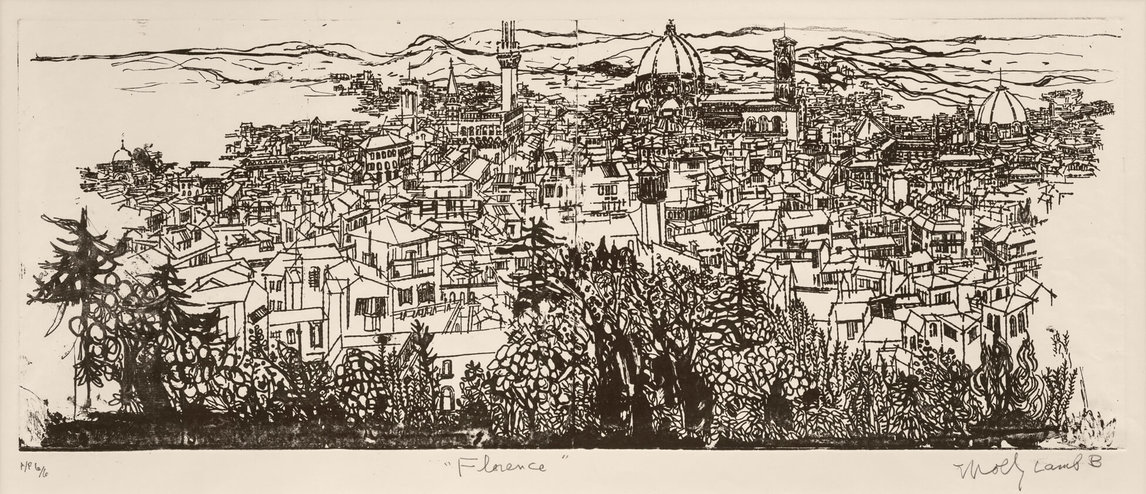

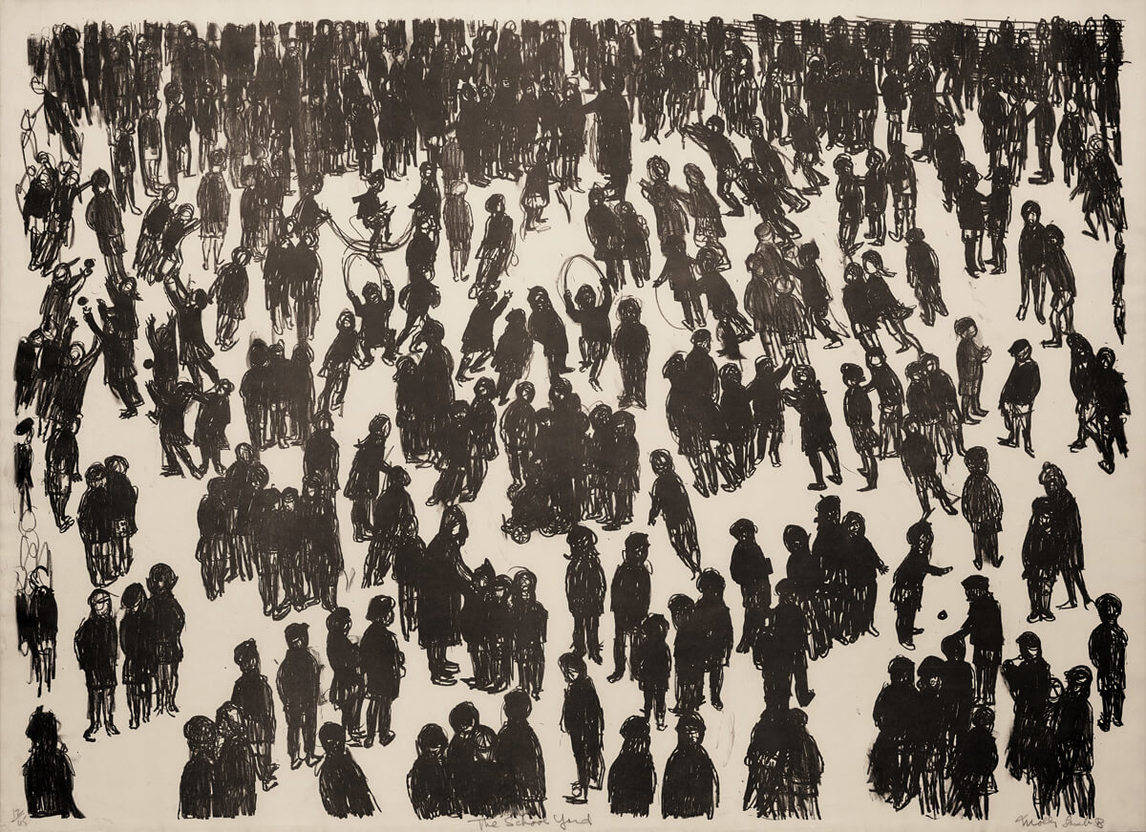

Printmaking makes fewer appearances in Lamb Bobak’s work, though the prints she made reveal her graphic sensibility in complicated compositions of crowds and grouped buildings. Lithographs from the late 1950s and early 1960s, including Florence, n.d., and The School Yard, 1962, show how she was able to transfer her feeling for crowded, active space from oils to prints.

Her serigraph The Ball, 1986, picks up the general composition of her canvas The Legislative Ball, 1986. Both depict dancers whose swiftly rendered forms make them float across the picture space; although the ballroom is anchored by three architectural elements—two windows and a door through which a Christmas tree is visible—its shape is not precisely defined.

While reviewers responded positively to her prints, Lamb Bobak mentioned her printmaking only in passing. In a 1962 interview she said she had intended to take classes in that medium during her stay in Oslo, but there is no record that she did. In 1978 she talked of helping her husband with his lithographic work and indicated she had done some herself, “in England, of course,” though her output was small.

Lamb Bobak’s illustrations for children’s books by Frances Itani, Sheree Fitch, and her own daughter, Anny Scoones, show clear connections to her early diaries from Galiano Island and the war years, particularly in their humour and sense of fun. They also display resemblances and differences with her artwork. Readers expect book illustrations to enhance the story, but since the 1950s Lamb Bobak had deliberately avoided using narrative in her paintings. This caution comes through in her images for Itani’s Linger by the Sea (1979), where she follows the storyline but remains remarkably detached, rendering the main characters as loosely defined figures.

In Fitch’s Toes in My Nose and Other Poems (1987) and Merry-Go-Day (1991), Lamb Bobak achieved a satisfying balance among all the elements: narrative, character, and the use of different techniques to express feelings. In “The Moon’s a Banana,” for example, a sleeping child forms the central image, but the dog and the teddy bear in the far right of the frame invite readers to extend their imagination beyond the words in the text. In Scoones’s A Tale of Merlin the Billy Dog (2000), the goat at the centre of the story frolics with his new friend (a black Labrador puppy), curls up to sleep, and at one hilarious point is menaced by a flock of “chicken bullies.” These and other later illustrations, act as comical extensions of the text.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements