Molly Lamb was the only Canadian woman during the Second World War to be appointed an official war artist and sent overseas. She immediately established herself as an artist of keen observation, wit, and humour. Although she and her husband, Bruno Bobak, settled on the periphery of Canadian art centres, in Vancouver and then in Fredericton, she remained international in outlook and connected with artists throughout Canada and abroad. As a painter of modern life, she focused on exuberant scenes of everyday life such as crowds, interiors, and, most popularly, flowers.

A Woman War Artist

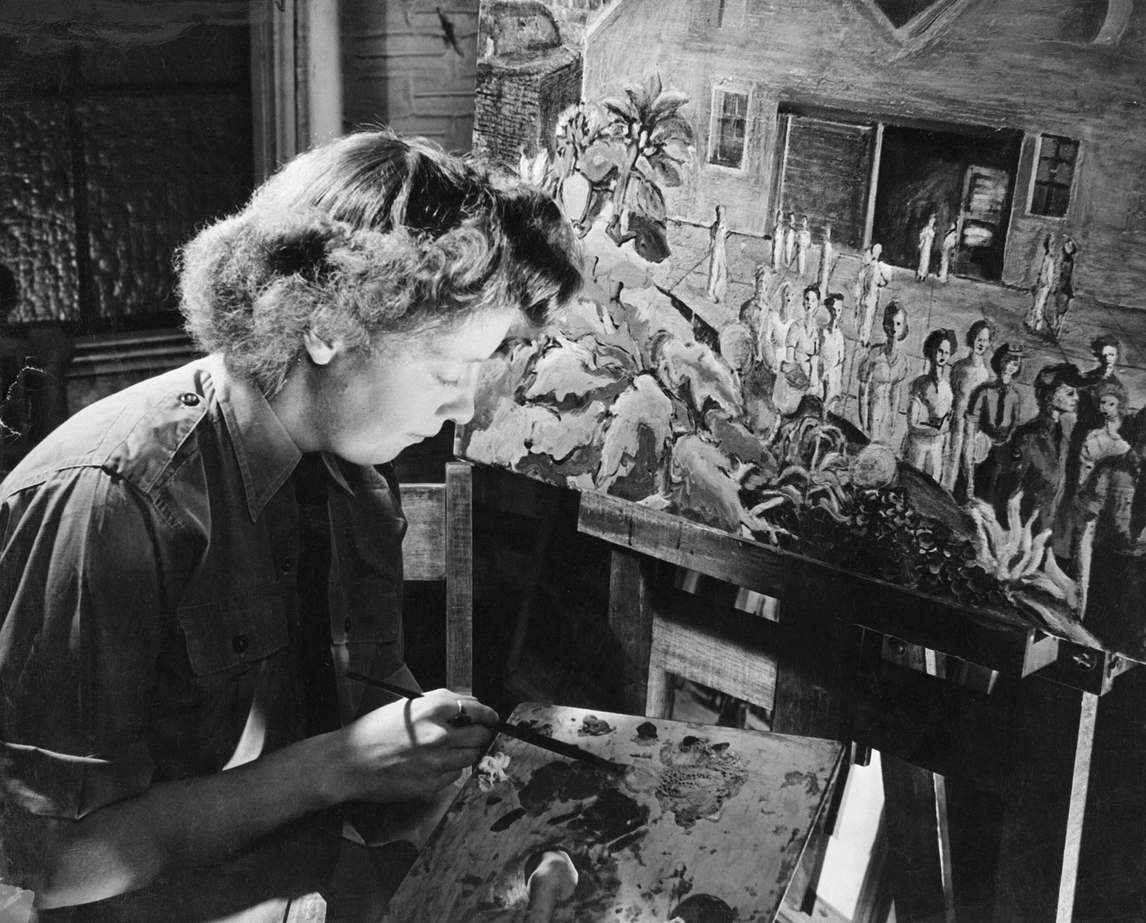

After almost two years of lobbying, in June 1945 Lieutenant Molly Lamb became the first and only woman accredited by the federal government as one of the thirty-two official Canadian war artists. The others, all of whom belonged to the Canadian Armed Forces, included Aba Bayefsky (1923–2001), Lawren P. Harris (1910–1994), Charles Comfort (1900–1994), Will Ogilvie (1901–1989), Alex Colville (1920–2013), and Bruno Bobak (1923–2012), whom she married later that same year.

Because Lamb was a woman, she was assigned to overseas duty only at the end of the war when hostilities in Europe had ceased. Colonel A.F. Duguid, director of the Canadian Army Historical Section and the army’s representative on the Canadian War Artists Selection Committee, stated in June 1943 that “from the Army’s point of view their [women’s] appointment was not desirable as the artists were at the scene of combat.” The National Gallery of Canada disagreed and commissioned Alma Duncan (1917–2004), Pegi Nicol MacLeod (1904–1949), and Paraskeva Clark (1898–1986) to document the war effort in Canada, focusing on women’s contributions and perspective. By the autumn of 1944 the War Artists Selection Committee proposed sending Lamb abroad as a war artist. Six months later, with Europe secured, she finally received permission to travel.

When asked years later whether she chose to focus on “the human element in the war effort away from the battlefront,” she replied:

They didn’t lay down any laws but the women weren’t near the battle ever. . . . The women were mostly behind the lines in Europe and the war was over anyway and so . . . if I saw Amsterdam . . . I would just put a few little CWACs [Canadian Women’s Army Corps] in the street and paint the city and that was valid. The CWACs were there . . . I think the government would have liked me to have painted the activities of the women, and I did—in laundries, as drivers and chauffeurs, and the pipe band, but then I also threw in a lot of my own ideas.

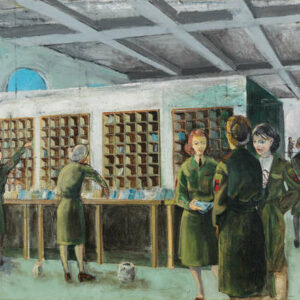

By focusing on the activities of the CWAC overseas, often in a humorous and positive sense, Lamb produced works similar to those she had composed in her illustrated war diary, W110278, during her years of service in Canada—for example, in Basic Trainees Learning to Stand at Ease, 1946. Brian Foss, who studied her work as a war artist, laments this likeness, though he acknowledges that she also challenged herself by producing sketches and paintings of the devastation of war, as in Ruins of Emmerich, Germany and Bremen Ruins at Night, both 1945.

Yet, despite the perceived limitations of this continuity in her work, Lamb’s documentation provides a rare look into the wartime activities of Canadian servicewomen. Her CWACs Sorting Mail, n.d., for example, illustrates activities performed by women far from the front lines that helped to maintain the war effort. Salmon in the Galley, 1944, and other commissioned works by Nicol MacLeod, serve the same purpose: as Nicol MacLeod explained, “Only if all the women painters in Canada were to cover all the activities of all the Women’s Divisions could this story ever be depicted properly.”

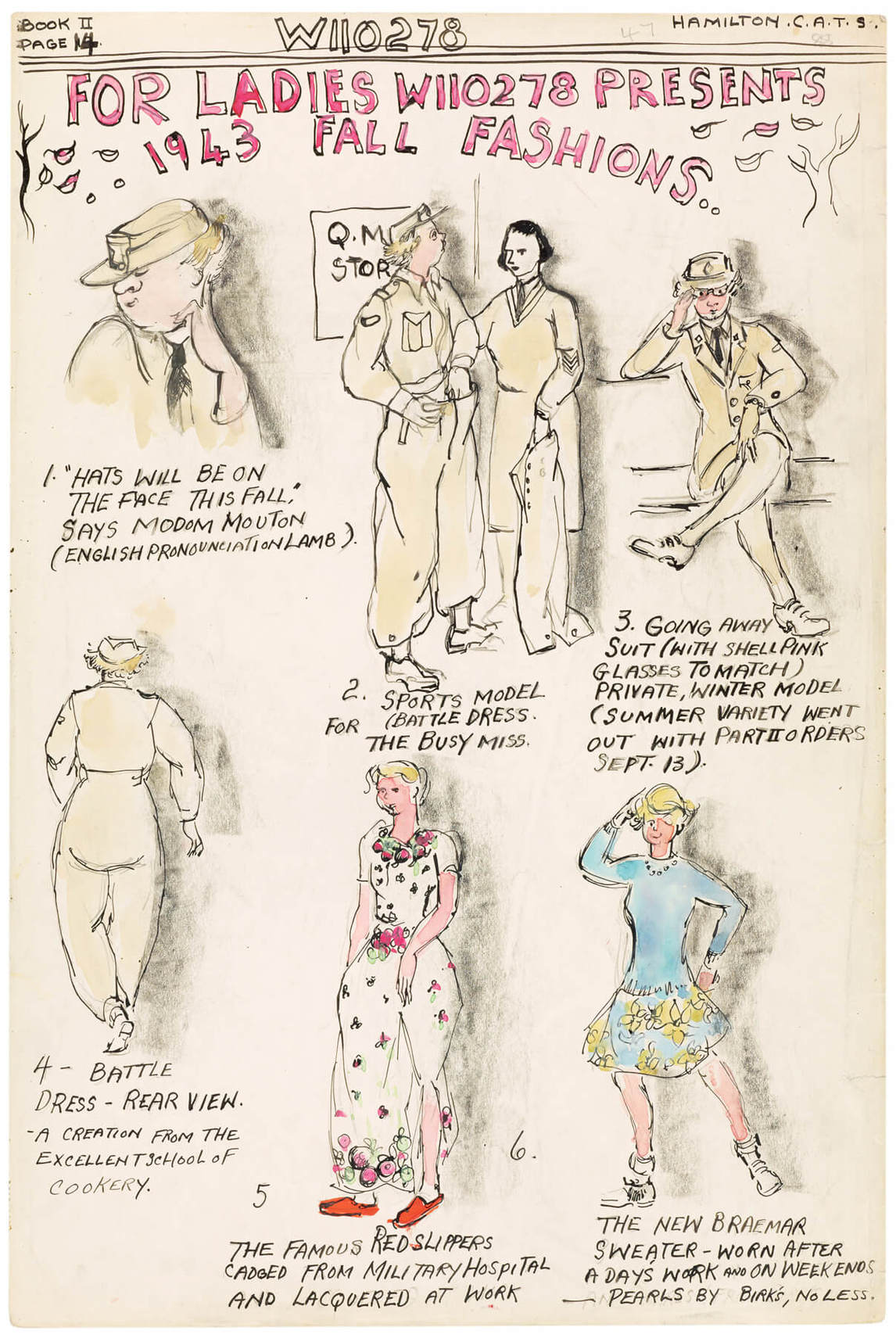

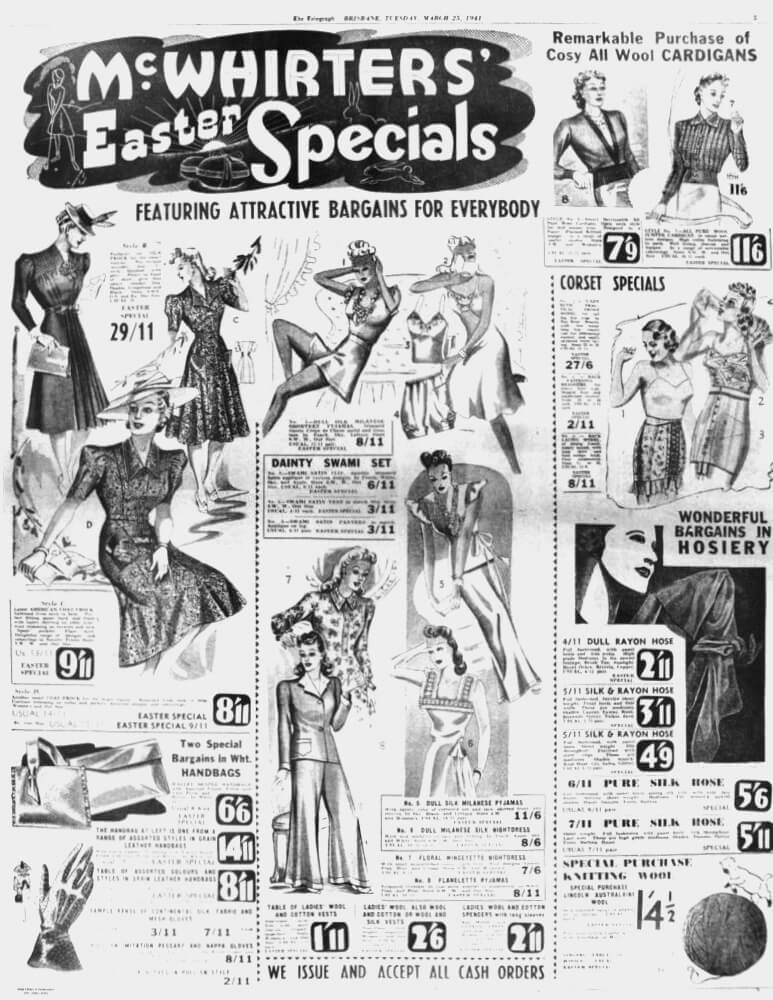

Lamb was no doubt aware of gender bias in both the army and the Canadian art world generally, but she usually dealt with such issues with parody and good humour. While military recruitment posters presented servicewomen in glamorous, idealized contexts to combat fears over the “de-feminization” of women in the military, Lamb used caricature to poke fun at these images. On one occasion in her diary she produced a special colour supplement titled “For Ladies[,] W110278 Presents 1943 Fall Fashions,” a work that was based on contemporary newspaper advertisements for women.

There she took on an alter ego, “Modom Mouton (English Pronounciation [sic] Lamb)”—a play on words that, Tanya Schaap notes, was intended to evoke the idiom “mutton dressed as a lamb.” “Hats will be on the face this fall,” Modom Mouton declares, but instead of a fashion model, Lamb depicts a servicewoman in her khaki army cap. Only in her portrait Private Roy, Canadian Women’s Army Corps, 1946, did Lamb present a striking contrast to the common depiction of women in the Canadian Armed Forces as ironically genteel and uniformly Caucasian.

Humour

Humour played a central role in Molly Lamb Bobak’s art, from her time at the Vancouver School of Art through to her later crowd scenes and book illustrations. It reflected her general joie de vivre and optimistic approach to life. Humour has been a key component in modern art practice since the early twentieth century, from Dada and Surrealism through Fluxus and Pop to the work in Canada of Greg Curnoe (1936–1992), for example. Recently, art historians have begun to explore the ways in which Canadian visual culture—private journals, broadsheets, and political publications—has been enriched by graphics imbued with wit and playfulness.

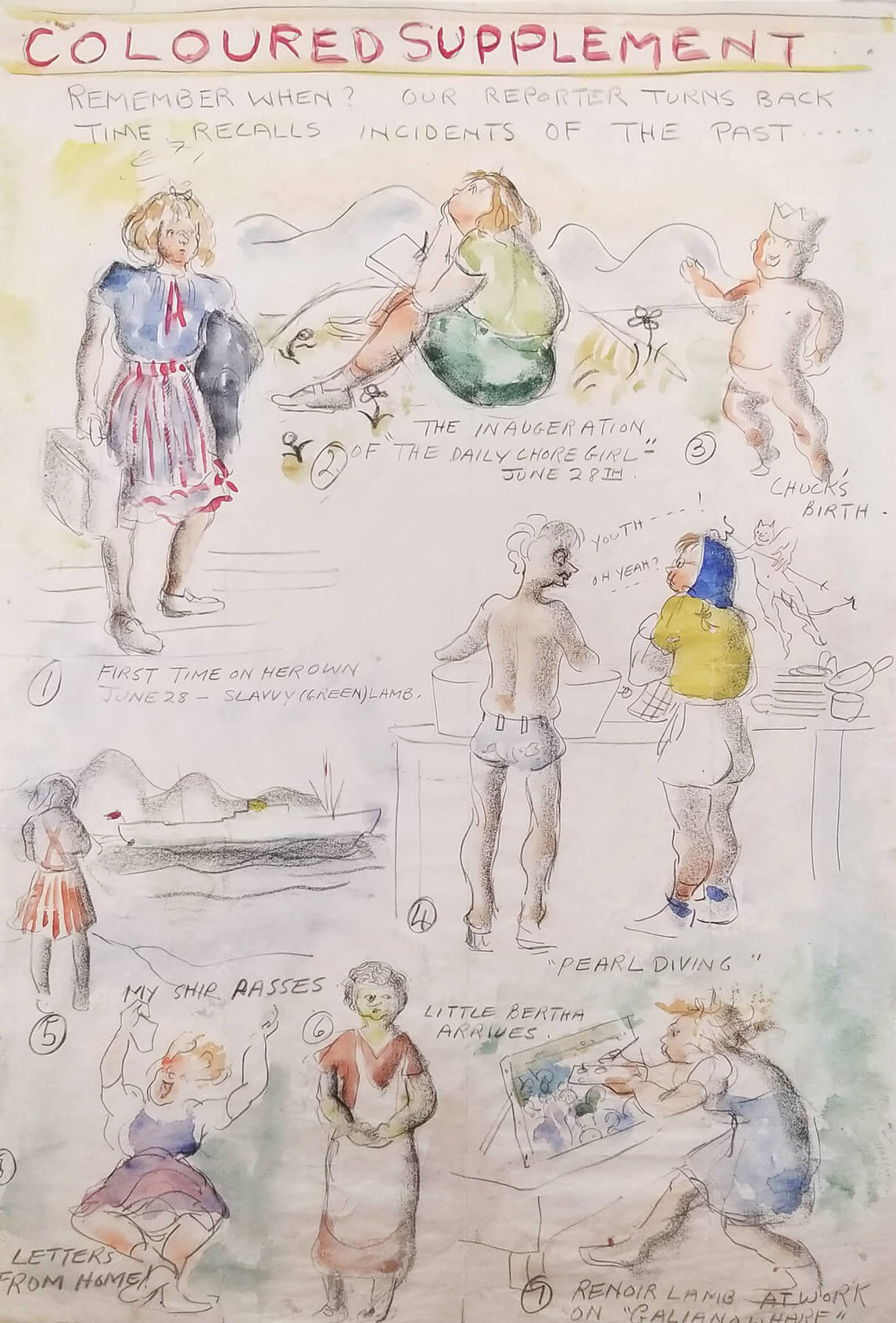

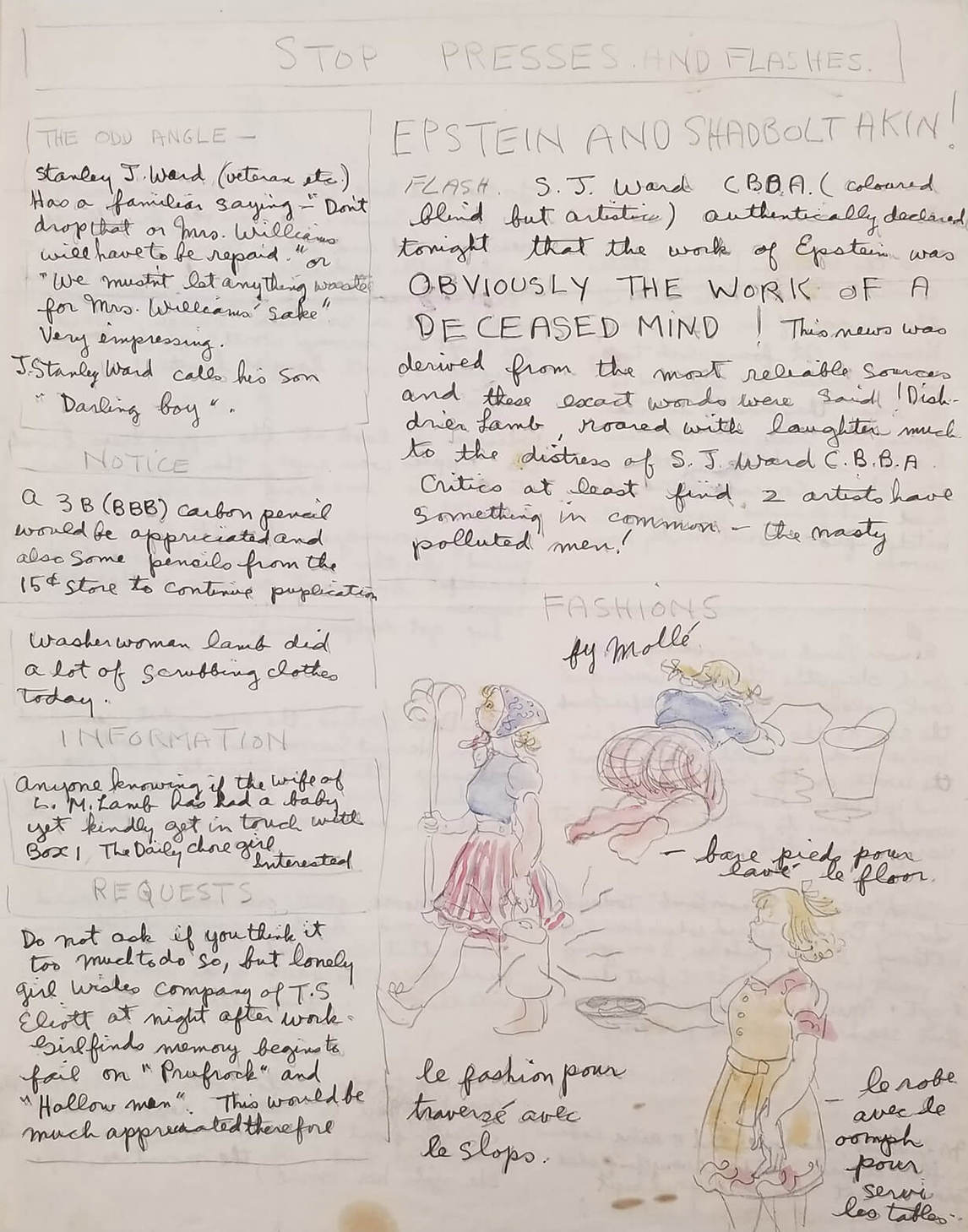

Lamb used humour to poke fun gently at the status quo. When she worked at the summer resort on Vancouver Island as a student, her diary, The Daily Chore Girl—Galiano’s Dish Rag, 1940, revealed her penchant for comedy through caricature and prose. She mocks herself by using various alter egos, including “Renoir Lamb” and “Slavvy.” One such “coloured supplement” from July 1940 positions Lamb alongside Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) and Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), painters she greatly admired. As these modern masters support her girlish figure, the caption reads: “Actual photo of 3 outcasts, M. Cézanne, M. Lamb, and M. Gauguin—All Wishing to Be Home.” The island road sign beside them points toward Vancouver. Another entry features “Fashions by Mollé,” illustrating Lamb in her work uniform carrying out various chores: “le fashion pour traversé avec le slops” and “le robe avec le oomph pour servi les tables.” Like the “painter of modern life” Constantin Guys (1802–1892), described by the poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), Lamb demonstrates an aptitude for detailed observation—the “particular beauty . . . of circumstances and the sketch of manners.”

Two years later, when Lamb joined the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC), she again kept a diary, W110278: The Personal War Records of Private Lamb, M., 1942–45, which mimicked a daily broadsheet in format and caricatured army life. Over three years, it records her feelings as a servicewoman—a combination of excitement and well-being somewhat at odds with a regimen where discipline and routine were paramount. As an artist, she wrote, the army offered her many benefits:

The whole structure of army life is agreeable to a painter. All the nuances of living are done away with because you don’t have to cook, you don’t have to worry about being poor or sick or being without warm clothes. And everywhere you turn there is something terrific to paint.

Best of all, Lamb Bobak noted, was the camaraderie with her fellow CWACs—“that, basically, we were all alike.” Gas Drill, 1944, demonstrates this group spirit as well as her propensity for caricature. The finished canvas was based on a sketch, “Drill, Drill, Drill as Guppies Turn Pro! Out in the Cold Cold Snow,” 1942, where a number of women in army uniform stand in the snow wearing gas masks, and that sketch was echoed in Untitled (Christmas Card), c.1995.

She playfully catches the confusion of “respirator drill day” as the recruits try but fail to execute commands that they cannot quite hear through the masks. As one CWAC recalls, “In Basic Training, if you hadn’t been able to laugh, you wouldn’t have been able to retain your sanity. In fact, there were a few who didn’t.”

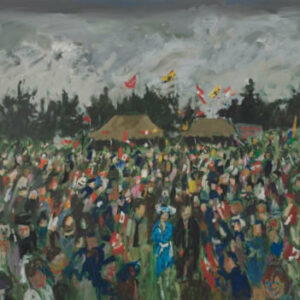

Lamb’s early inclination toward caricature and parody comes through in her later work in subtle ways. In The Tea, Fredericton, 1964, she gently pokes fun at Fredericton’s society women for taking themselves too seriously. Similarly, John, Dick, and the Queen, 1977, offers a humorous representation of the royal visit to New Brunswick, where Queen Elizabeth II stands out in the crowd distinguished by her cartoonish blue dress and beaming red smile.

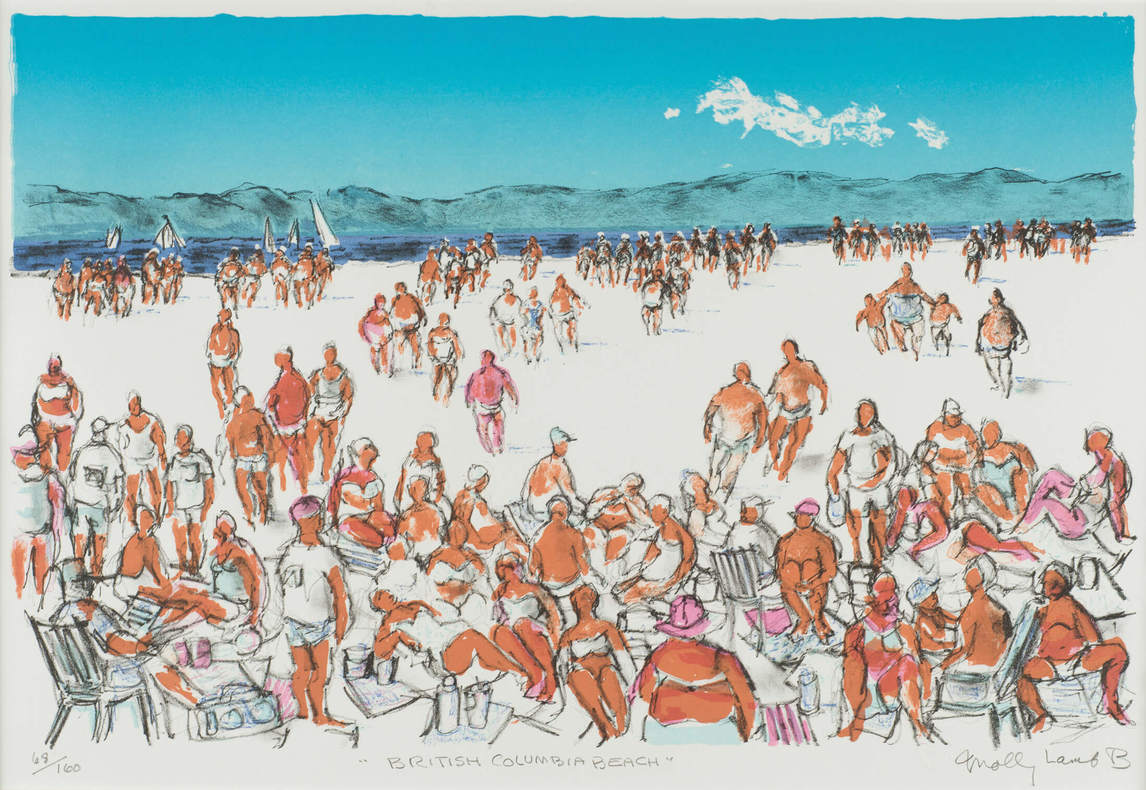

In British Columbia Beach, 1993, a lithograph Lamb Bobak produced to raise funds for Artists for Kids, the red, sunburned bodies she depicts on the white sand led curator Ian Thom to quip, “Fredericton bodies on a B.C. Beach.”

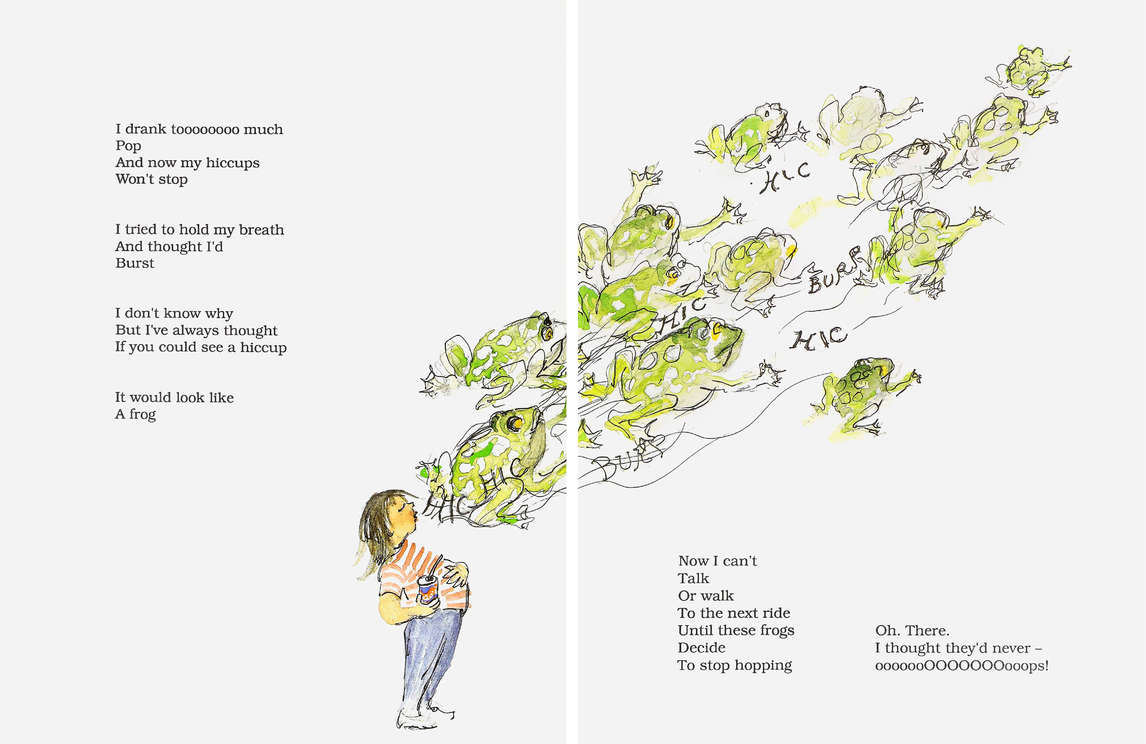

While playful tendencies are often subdued in Lamb Bobak’s crowd scenes, they return as an explicit component of her work in illustrations for children’s books, such as those by Sheree Fitch and Anny Scoones, the Bobaks’ daughter. Using a caricature-based style similar to what she used in her wartime journals, in Merry-Go-Day (1991) Lamb Bobak adds personality and a rich narrative to scenes where Fitch’s protagonists romp through the Fredericton Exhibition and eat too much fair food. Throughout, she relies on an illustrative approach to the text that she resisted in her paintings. In Scoones’s A Tale of Merlin the Billy Dog (2000), she depicts the goat, Merlin, as dog-like and slightly bumbling, even as she captures the absurdities of daily life through sharp observation.

An International Outlook

Molly Lamb Bobak spent most of her career working as a figurative (or representational) painter, first in Vancouver and later in Fredericton, but her work never conformed to the regionalist flavour of either coast. In both Canada and the United States, regionalism was seen as a rejection of European-style modernism in favour of local, often rural subject matter. Wherever Lamb Bobak lived, she maintained close connections with painters in Canada’s key centres of artistic activity. She also kept abreast of international modernist trends and allowed important European and American artists to influence her painting—Paul Cézanne and Red Grooms (b.1937), for example.

After brief periods in Toronto and Ottawa following the war, the Bobak family moved to British Columbia, where, in the fall of 1947, Bruno Bobak began teaching at the Vancouver School of Art. There they became part of a community of artists that included Jack Shadbolt (1909–1998) and his wife, the writer Doris Shadbolt (1918–2003), Jack Nichols (1921–2009), Lawren Harris (1885–1970), Audrey Capal Doray (b.1931), architects Arthur Erickson (1924–2009) and Ron Thom (1923–1986), and several other painters who had also served overseas in the war. The Bobaks found themselves among a new generation of artists who were trying to integrate art and design into the everyday life of communities.

In the 1950s many of these Vancouver artists expressed a renewed interest in integrating nature into art. The Bobaks and Shadbolts, however, took a different slant and introduced modern British artistic ideas and imagery to the city. During the war, while in London, they had encountered works by Paul Nash (1889–1946), Graham Sutherland (1903–1980), Henry Moore (1898–1886), and Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975), and Lamb Bobak had also seen an exhibition of contemporary British art at the National Gallery of Canada in 1944. In the 1950s she experimented with geometric elements in her work. In North Vancouver Ferry, 1950, for example, a quasi-cubist quality gives shape to the featureless passengers, the division of space is geometric, and the diverging perspectives collide. In Still Life, 1951, too, she abandons traditional perspective and veers toward geometric abstraction.

Alan Jarvis (1915–1972), the director of the National Gallery of Canada, and R.H. Hubbard (1916–1989), his curator of Canadian art, singled out this particular group of artists working on the West Coast. Jarvis was quoted in the British periodical The Studio in 1957 as saying, “There are more good artists per square mile in BC than in all the rest of the country.” Although these painters—Takao Tanabe (b.1926) and Donald Jarvis (1923–2001), along with other artists including Shadbolt and the Bobaks—did not consider themselves a “school” or adhere to common styles or philosophies, they shared an attitude toward the landscape and its representation.

Lamb Bobak’s Grain Boats at English Bay, Vancouver Harbour, n.d., captures her impressions of the waterfront, with the densely crowded beach set against the freighters floating in the distance. Her short brush strokes and diffuse rendering of the bathers encourage viewers to focus on the scene as a whole—a summer’s day at the beach. Bruno Bobak’s canvases from this time, in contrast, are more symbolic in their gestural and expressionist treatment—for example, Vancouver Harbour, c.1959, and Springtime in North Vancouver, 1960.

In 1961, after several years of working and travelling in Europe, the Bobak family settled in Fredericton, where Bruno and Molly quickly became core members of another creative group. Together with poets Fred Cogswell, Alden Nowlan, and Robert Gibbs, they were integral in bringing together painters, writers, and thinkers to define an era that has been described as a golden age for art in New Brunswick. The province is noted for its decentralized arts scene, with each city defined by key artists: Alex Colville, Christopher Pratt (b.1935), and Mary Pratt (1935–2018) with Sackville; Jack Humphrey (1901–1967) and Miller Brittain (1912–1968) with Saint John; Claude Roussel (b.1930) and Roméo Savoie (b.1928) with Moncton; and Bruno and Molly Lamb Bobak with Fredericton. With few exceptions, they all worked in a realist and representative manner.

However, neither Bruno nor Molly Lamb Bobak can be classified as regional artists. Although they helped to define Fredericton as an art centre, they were not defined by the city or the region. Painting landscapes of specific places, so important for artists such as Goodridge Roberts (1904–1974), was less important to Lamb Bobak. Still, her highly individual and modernist response to the cities of Vancouver, Victoria, and Fredericton and to local scenery in New Brunswick is a critical aspect of her artistic creation—as in the colourfully and gesturally rendered Shediac Beach, (N.B.), 1972, and Montague Beach, Galiano Island, c.1990.

In her art, Lamb Bobak was always influenced by “artists from away”—modern painters such as Joseph Plaskett (1918–2014) in Paris, Kenneth Hayes Miller (1876–1952) at the Art Students League in New York, and Frances-Anne Johnston (1918–1987), who inspired her to explore and push the language of painting in her compositions. Lamb Bobak shipped her paintings to galleries in other cities—Kastel Gallery, Galerie Walter Klinkhoff, and Waddington’s in Montreal, the Roberts Gallery in Toronto, and the New Design Gallery in Vancouver—where they were bought by collectors and viewed by local art lovers. She also exhibited her work widely throughout Canada in both solo and group exhibitions. In 1959 she represented Canada at the Bienal de São Paulo and participated in the International Print Exhibition held in Lugano, Switzerland. In 1966 her work was celebrated alongside her contemporaries in Atlantic Canada with a large exhibition organized by the National Gallery of Canada. And in 1993 the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina organized a major touring retrospective exhibition and catalogue of her work.

Crowd Scenes and Flowers

Molly Lamb Bobak generally sketched or painted everyday life. However, she became well known for two subjects in particular: crowd scenes and flower paintings. A 2018 exhibition entitled Talk of the Town organized by the Burnaby Art Gallery featured Lamb Bobak’s unique ability to capture the pulse of crowds from a variety of vantage points. As curator Hilary Letwin notes: “Molly Lamb Bobak’s paintings are full of talk: people excitedly calling to each other in the crowd, chatting about this and that, whispering the latest gossip on a street corner.”

These crowd scenes represent Lamb Bobak’s commitment to translating her impressions of lived experience, and, to capture their immediacy, she first sketched what she saw. She had developed this technique in her early illustrated diaries from Galiano Island and during her years with the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (W110278: The Personal War Records of Private Lamb, M., 1942–45). The faces in the crowds are loosely drawn and devoid of detail, but the language of modern life is clear in the gestures of the bodies gathered together. When she was appointed an official war artist at the war’s end, she continued to produce crowd scenes in her paintings—for example, in CWACs on Leave in Amsterdam, September, 1945, 1946.

When Lamb Bobak settled in Fredericton in the early 1960s, she often painted or was commissioned to record images of people gathered together in celebrations or leisure activities—for example, Rink Theme—Skaters, 1969, or John, Dick, and the Queen, 1977.

By 1960, Molly Lamb Bobak was painting compositions of flowers in both watercolour and oil—and she continued to sketch flowers all her life. These images remain among the most popular of her paintings with collectors. She credited her interest in flowers and in watercolour to her husband, Bruno Bobak: “I think the reason I started painting watercolours was very simply because Bruno painted watercolours of flowers.” His painting Molly’s Garden, n.d., attests to her talent in tending a garden—a skill she learned from her mother—but wildflowers were her real passion. As she noted: “It’s the rambling flowers that fascinate me. That’s why I love New Brunswick so much—it’s full of wild, hardy flowers.”

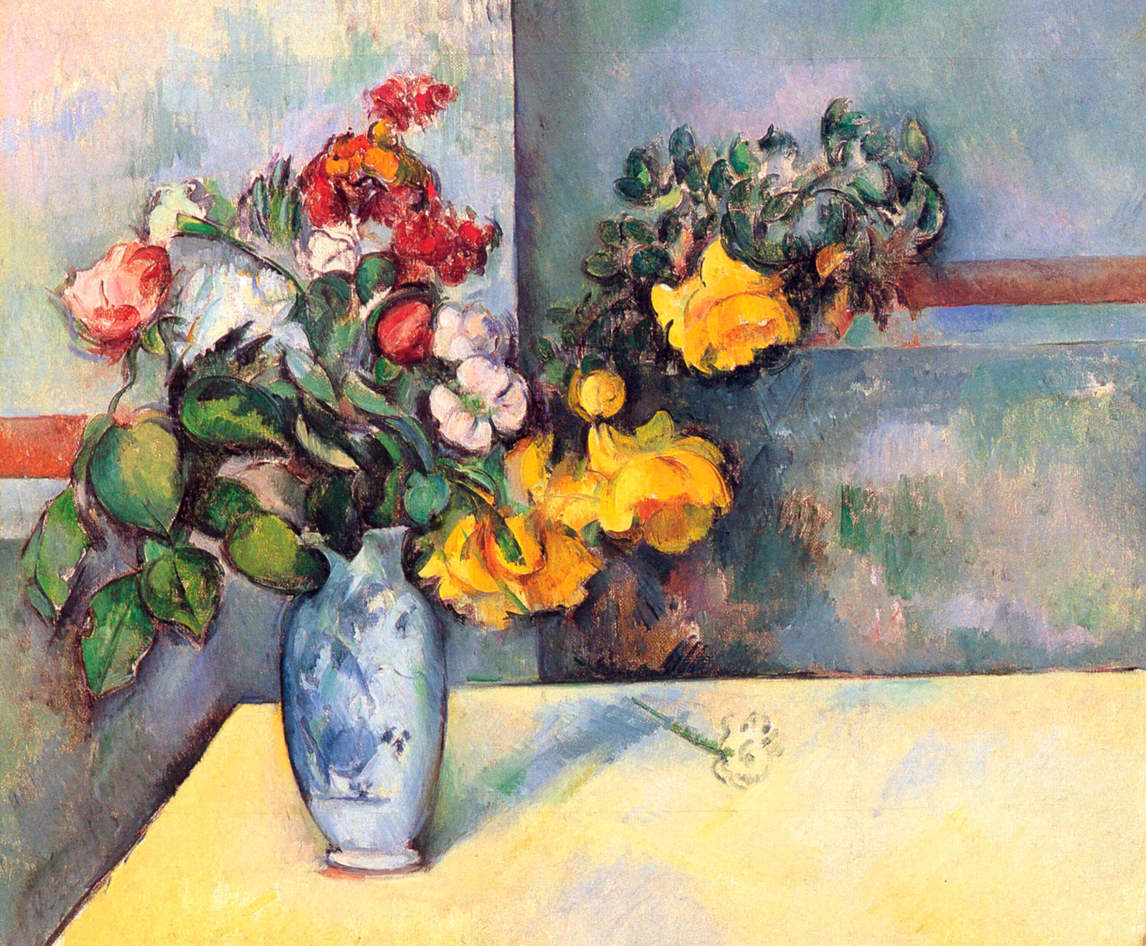

Although artists such as Paul Cézanne and Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) are famous for their images of water lilies, sunflowers, and irises, flower painting has traditionally been regarded as an acceptable genre for women. It has even been viewed as a lesser form of art than historical or religious subjects precisely because of its association with women’s interests and “gentility.” Art critics might read Lamb Bobak’s focus on interiors and flowers as revealing her respect for gender roles, but, to her, flowers were simply “the most pure things that I paint.” As an independent woman, she expressed her sheer joy in nature and painted the world as she saw it.

Lamb Bobak also rendered her flower subjects in a variety of styles. In White Tulips, 1956, for example, she veered toward the abstract. She likened her flower images to her paintings of crowds, describing both as studies of forms in space: “Flowers are like crowds,” she said, “they move in the wind. You don’t organize them. . . . You paint them as they are.” In this way she conferred an intellectual and modernist treatment on her flower studies.

Perhaps Lamb Bobak’s greatest achievements as a painter were the singular vision and keen observation she brought to her scenes of modern life. Her vivid scenes of local community events made a unique contribution to painting in New Brunswick. Her approach was markedly different from the social realism of painters such as Miller Brittain, who, for the most part, depicted working-class scenes. What stands out in all her work—flowers, interiors, still-life compositions, and community groupings—is her love for the beauty of ordinary life.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements