Michael Snow is a polymath. His work is all about form, which he treats carefully in terms specific to the medium, whether material, spatial, or temporal. But if Snow strives in his work for optimal sensorial experience, he does so within systems of balance and contrasts that clarify impressions by sharpening distinctions. In this he has been influenced by philosophies of mind and language, phenomenology and environmentalism.

Style

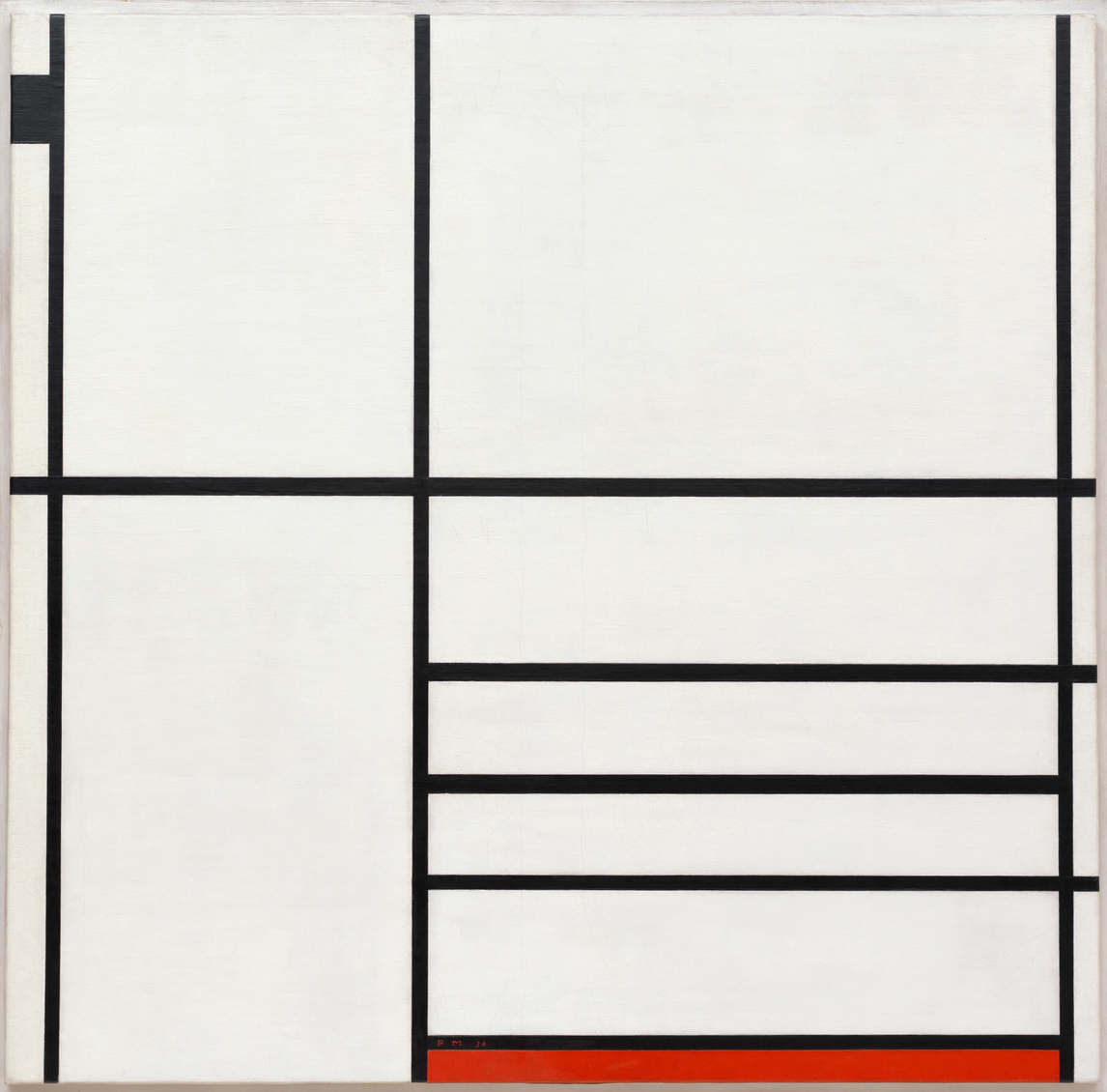

As a visual artist, Snow belongs to a generation that was truly inspired by early twentieth-century European art—Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), Paul Klee (1879–1940), Henri Matisse (1869–1954), and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) are key references—as well as the vitality of the New York School, principally Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) and Willem de Kooning (1904–1997). Snow has always respected the purity of their endeavours. Their way of thinking about art, more than its stylistic expression, has been carried forward in his work, somewhat complicated by the countervailing influences of Dada and Fluxus, especially the definition by Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) of the art object as something authorized by an artist. These examples licensed Snow to experiment with technology, as well as with the humblest materials at hand, and sometimes to perform the role of the artist in his work.

Snow has ferociously resisted correlations with the dominant movements of his day, Pop and Minimalism, but also with Conceptual art, with which he is sometimes connected, for as he has repeatedly asserted, his work is about form. In 1969 the American film theorist P. Adams Sitney coined the term Structural film, citing Wavelength, 1966–67, as a key work, and this label on Snow’s oeuvre has been the stickiest, as long as Structural film, which points to the essential aspects of the medium, is not confused with Structuralism, which essentializes or systematizes human experience. In refusing to be pigeonholed as a Minimalist, Snow himself has suggested that he might be considered a “maximalist.” This term is not available, as it is associated with Russian revolutionary politics, but the reader will get the idea.

Theory

Michael Snow’s dialectical process has led his audiences through many of the problems and issues of modernism and postmodernism, in part by offering alternatives to strict orthodoxies. His modernism is performative; his postmodernism is paradoxically purist. In this he is well met by visual art theorists such as Hubert Damisch and Thierry de Duve in their phenomenological and semiological readings of visual art experience. Snow began reading philosophy as a teenager; his published conversations with Bruce Elder (b. 1947) are replete with references to the history of thought, from Plato to Wittgenstein.

Canada Council Art Bank, Ottawa.

In 1984 a special issue of the journal diacritics aligned Snow’s work with the foundations of postmodernism—the ideas of Jean-François Lyotard—by commissioning it for the cover and inside pages. His work has been correlated with haptic theory by Martha Langford (2001) and Jean Arnaud (2005) as part of the reinvigoration of phenomenology through projective sense perception. As for methodology, as sociological and political theory has refined it over the past sixty years, it is perhaps easiest to say what Snow is not. He is not a social artist, nor is his work political, except as it has stood for liberal values of freedom of expression, recognition of intellectual property and moral rights, public education, and the importance of state and private investment in the support of culture.

Technique

Michael Snow has used almost every medium and technique encountered in a contemporary art museum or cinema. His work is generally divided into three categories: visual art, ranging from early works on paper to holography; film, video, and cinematic installations; and music/sound, which includes both live performances and gallery works in which sound is a key element. These divisions are reflected in three books, from a series of four, published to coincide with his 1994 retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario and The Power Plant in Toronto, The Michael Snow Project; the fourth book, a collection of Snow’s writing, pulls his activities together by revealing the workings of his mind over many years. The Toronto retrospective, and by extension these publications, predates Snow’s involvement with digital media—his creation of DVDs and video projections in galleries in the twenty-first century. Since 2000 he has also given many more improvisational concerts in relation to his exhibitions. Add to that the theoretical attention to the performative nature of his work. The three facets of Snow’s creativity—visual art, cinema, and sound—are now widely understood as complementary.

Careful orchestration has always been Snow’s way of working. His projects match perception, memory, and imagination to medium and process. The human factor is, and has always been, explicit in the making of his work and its shaping of our understanding. In drawing, painting, carving, moulding, folding, panning, and performing to make visual art or music, what matters is the mark, the handprint, or the physical energy of the artist.

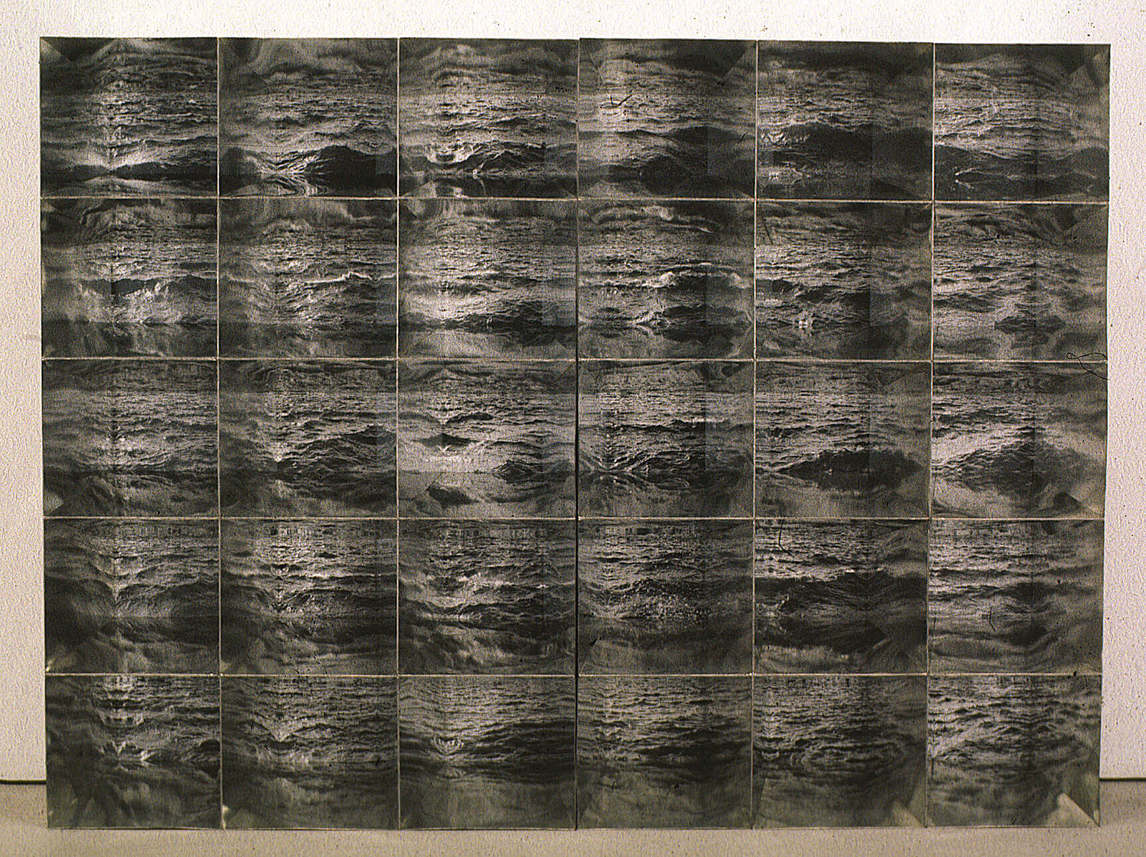

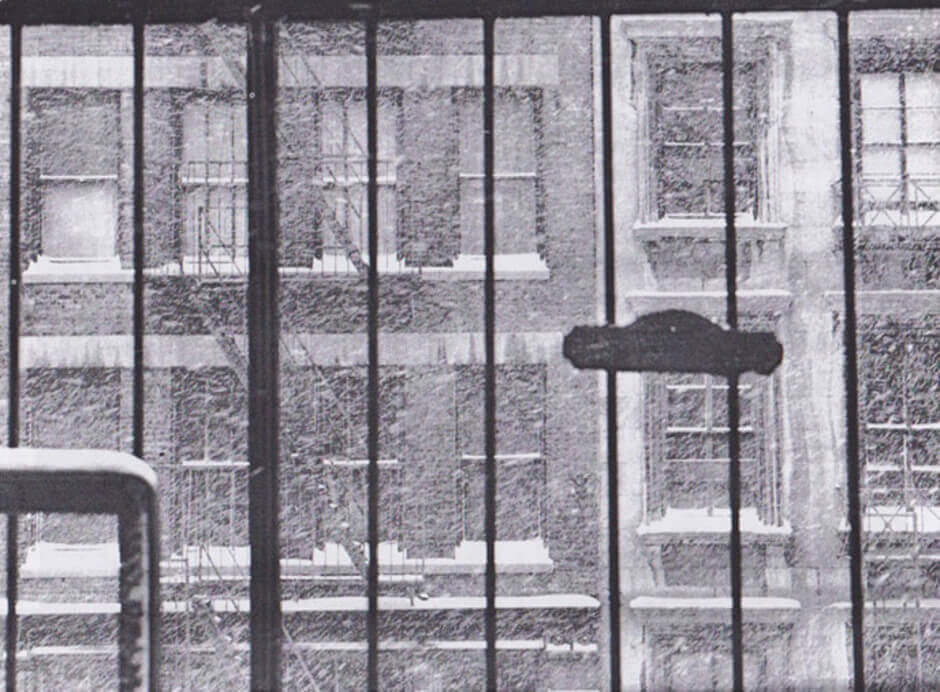

Any work could be offered up as an example; some are particularly striking. In the early 1980s Snow was taking photographs that fulfilled his ideal of making “the entire photographic image.” He was distinguishing his photographic work from modernism’s art of observation, and especially the summary statement of the “decisive moment.” Snow has used photography as a tool for protracted, meditative creation since the 1960s. His multiple image work Snow Storm, 1967—in which monochromatic images taken from his window are embedded in an enamelled Masonite field—is a study in greys. A related work, Atlantic, 1967, melds the photographic image with sculptural concerns. Snow’s concept of the “made-to-be-photographed” image likewise intersects with still life and sculpture; sometimes he adds watercolour to the black and white prints, as in Meeting of Measures, 1983, risking the purity of the photograph to underline its genesis as a handmade object from an artist’s studio. In these projects Snow also plays with materiality and scale to create visual juxtapositions—little handmade puzzles.

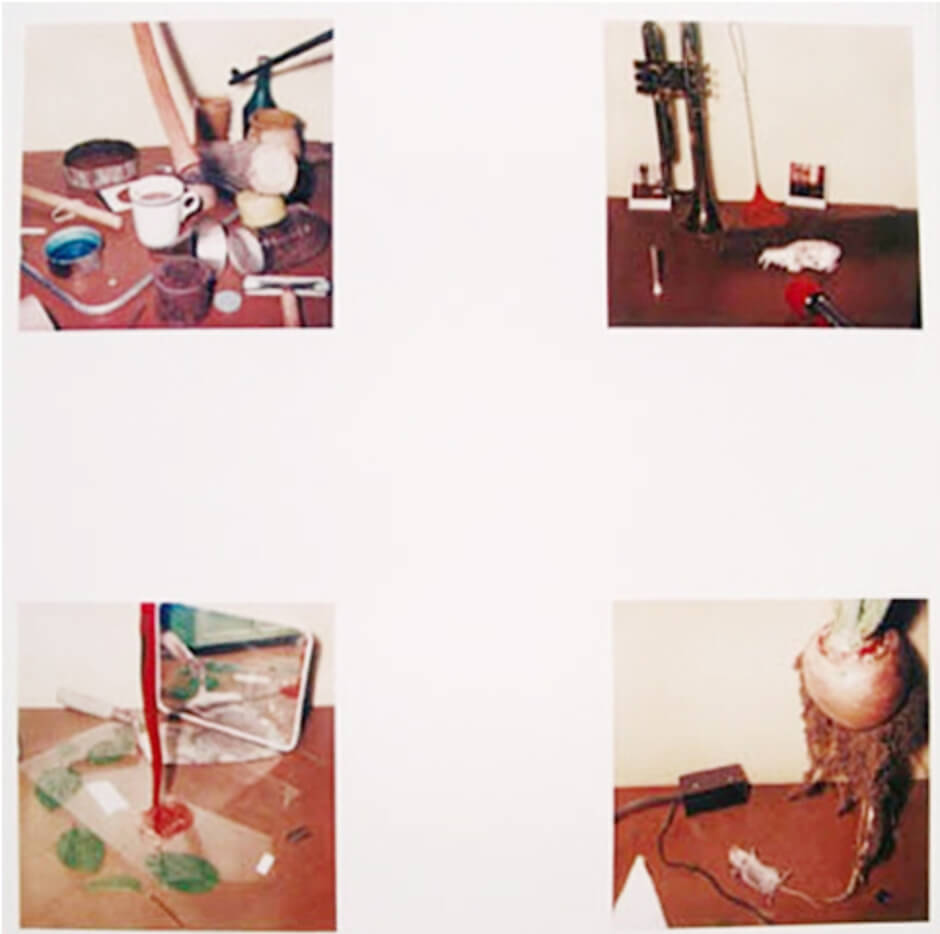

He also proposes correspondences, in the form of objects grouped together in front of the camera. An important work in this regard is Digest, 1970–98, whose stack of twenty-three colour images records the making of a three-dimensional subject, an aluminum container filled with plastic objects that have been immersed in plastic. Never a denizen of the darkroom, Snow has frequently used a Polaroid camera to produce an instant translation from split-second external reality to fixed image-object. His autobiographical suite Still Living–9 x 4 Acts–Scene 1, 1982, proposes coded correspondences that are further complicated in their arrangement as quartets of dye-transfer images on a sheet. Similarly, in more ambitious commissions, assemblages, or installations, the extended presence of the artist—the sense that we are sharing his creative space—is crucial to our appreciation of the work. Snow has also commissioned or collaborated with engineers, fabricators, photographers, and technicians to execute his ideas. In these cases, elements or entire art objects are authorized by the artist. His approach to these matters has developed on a case-by-case basis, sometimes driven by sheer practicality, but his work nevertheless can be taken as a guide to the changes in working methods that occurred during the rapid industrialization and technologization of art in the second half of the twentieth century.

About the Author

About the Author

Download PDF

Download PDF

Credits

Credits