The defining moments of Michael Snow’s life and career illuminate the history of Canadian art since the Second World War. In concert with the development of a unique culture, a national identity, and an international presence was the creative impetus among Canadians to rethink art in relation to process, technology, and everyday experience. Snow’s process has been additive. A leading figure in new media and Conceptual art, Snow has never rejected painting and sculpture, measuring his own achievements alongside the work that inspired his generation.

Critical Reception

Since the 1960s Snow’s work has been at the leading edge of visual art and experimental film. The first Canadian artist to be given a solo exhibition at the Venice Biennale, he also introduced photography as an art form to the Canadian pavilion, and his award-winning films were screened as part of the official program. The National Gallery of Canada’s acquisition of Snow’s photographic work Authorization, 1969, established a new direction within the area of contemporary art; the museum also acquired prints of his major films.

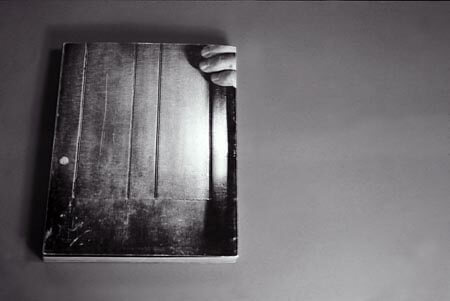

Over the course of his long career, Snow’s work has ensured a strong Canadian presence in important European and American collections, such as the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and at international film festivals. Snow was a visiting artist during the heyday of the Nova Scotia College of Art & Design in the 1970s; he occasionally taught there, and it was also where he edited the raw footage of La Région Centrale, 1971. NSCAD’s famed Lithography Workshop issued his Walking Woman photolithograph Projection, 1970, and its press published his artist’s book Cover to Cover, 1975.

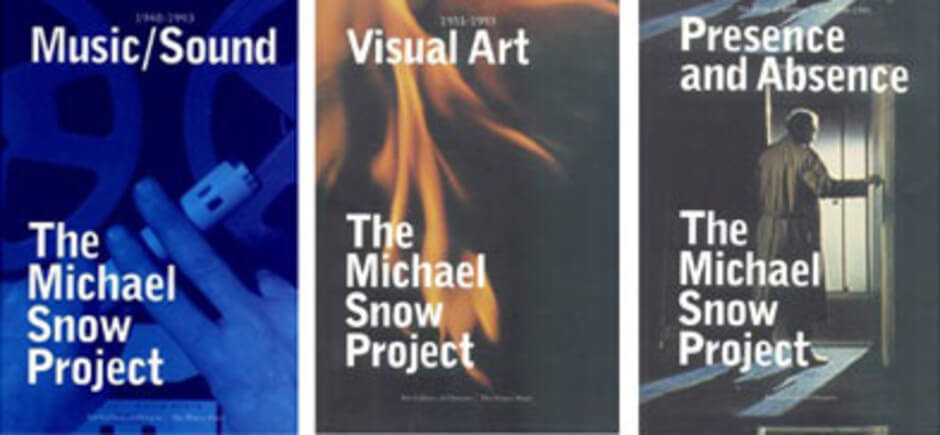

In Canada Snow’s work has been championed by curators such as Louise Déry, Louise Dompierre, Dennis Reid, Brydon Smith, Pierre Théberge, and Dennis Young. It has been pivotal in world’s fairs and thematic exhibitions organized by Thierry de Duve and the curator and writer Peggy Gale. The unprecedented Michael Snow Project, co-organized by the Art Gallery of Ontario and The Power Plant in Toronto, displayed those institutions’ curatorial strengths: the encyclopedic knowledge of Canadian art history commanded by Dennis Reid, the theoretical acumen of Philip Monk, and the research into contemporary practice deployed by Louise Dompierre.

Critical attention to Snow’s work has been steady and influential, generating articles in specialist journals and magazines, such as Artforum, artscanada, Border Crossings, Canadian Art, Film Culture, October, Parachute, and Trafic, by key theorists such as Raymond Bellour, Thierry de Duve, Bruce Elder, Annette Michelson, Chantal Pontbriand, and P. Adams Sitney. The emergent generation of media artists and theorists also finds much to appreciate in Snow’s work, as evidenced by homages, appropriations, and continuous activity on the blogosphere.

Defying Classification

In notes published to accompany the DVD-ROM Anarchive 2: Digital Snow, 2002, Michael Snow lists twelve key themes in his work: light, materiality, re-presentation (variation that alters meaning), reflection, transparency, duration, look, framing, scale, recto-verso, improvisation, and composition. Each of these themes, explicitly or on inspection, contains its opposite: duality is a guiding principle in Snow’s perceptual and conceptual system. From his earliest professional activities, we see combinations of materials and methods producing objects that are difficult to classify as painting, sculpture, or photography; we are constantly faced with hyphenations, or categories that imply pairs, such as “bas-relief”; these pairs are invariably complicated by other considerations that keep Snow’s audiences active and inquiring, as he challenges stylistic and institutional boundaries.

Snow himself is an intellectually restless man. The various trajectories of his mature work can be difficult to untangle. Before the Walking Woman series, and with increasing focus over the Walking Woman years, his ideas took the shape of questions about the very nature of art. As a young painter and sculptor, beginning in the 1950s, Snow maintained a traditional studio practice, one project leading systematically to another, with regularly scheduled exhibitions. This process became far more complex during the New York years, 1962–72, as he added photography and film to his repertoire, working simultaneously along parallel tracks.

His notebooks are storehouses of recognitions and injunctions—flashes of insight to which he intends to give form. Some sketches signal his persistent attachment to painting and sculpture, while others previsualize a photographic image or a scripted scene. Snippets of language offer early intimations of his monumental sound film Rameau’s Nephew by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen, 1972–74. Other insights are plainly on hold until a technological solution can be found for their execution. This was the case with *Corpus Callosum, 2002, which called for cinematic effects to stretch, compress, mould, and melt figures, objects, and sets. Snow had thought about this film for nearly a decade before digital technology caught up with his vision.

During that time he produced a number of works—paintings and sculptures—that relate to the film, and there are also multiple indications in the first decade of his career of his fascination with what we might call visual or material “distortion”—a term that he categorically rejects. These works form clusters, or multi-generational families of resemblance, that challenge disciplinary conventions of genre or style, making it more fruitful to look for patterns. Most were established quite early in his work.

Repetition with a Difference

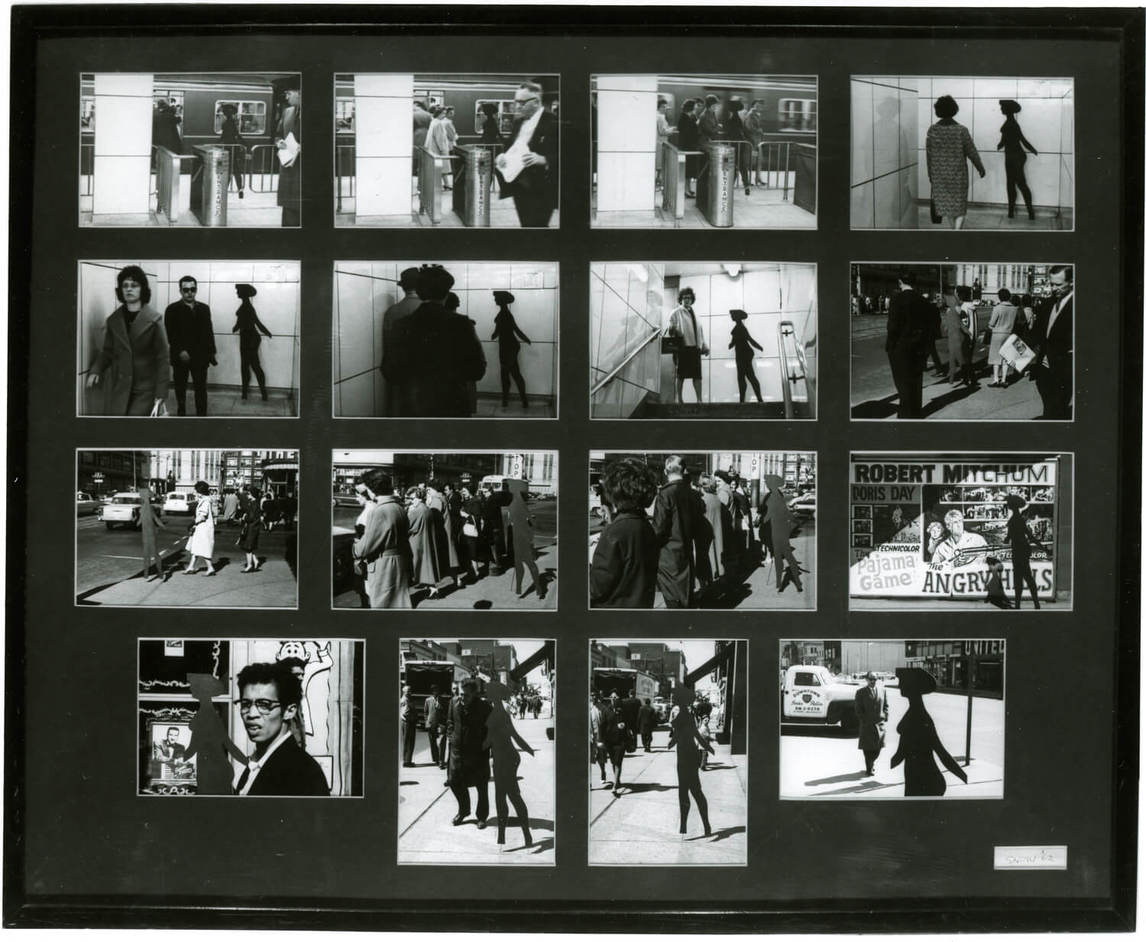

In 1961, before moving to New York, Snow had embarked on the long-term project that for six years would be his trademark: the Walking Woman. His insight was that a single form, considered as both a positive (a presence to be looked at) and a negative (an absence to be looked through), offered an infinite number of creative possibilities. He also recognized that an artistic practice arising from this intuition was both timely and original, participating in and commenting on a capitalist culture of innovation, industrialization, and communication.

Artists associated with Pop art or the later Minimalism shared this awareness, appropriating popular culture’s emblems and industry’s processes. Snow distinguished himself by creating his own trademark, which was a significant difference and a broadly appealing form of serious play. The creative uses of the Walking Woman—what Snow puts the iconic form through—always translates into new ways of looking, whether he is using it as a surface or a window, whether varying its colour, texture, pattern, material, or scale, whether presenting it on the street or in the cinema.

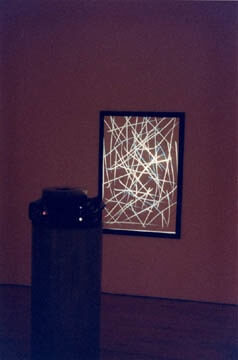

Repetition with a difference, or re-presentation, became an important feature of Snow’s photographic work. Sink, 1970, can be read biographically as symbolizing his transition from painting to photography, or, more persuasively, as demonstrating the coherence of his work. The work involves eighty colour slides—the full contents of a carousel projector tray—of a painter’s sink shot from a fixed position, but the image is varied through the use of gels. The slides are projected beside a photographic print of the same subject. But the work is also concerned with problems of representation—the translation of sense perception into language as mediated by photographic technology.

Contemplating Sink leads quickly to the conclusion that two photographic objects—a print and a slide—are very different, but the work just as quickly becomes a meditation on light and its transformative agency, whether through direct human intervention (a gel) or through human attention to the quality and quantity of light as it changes over the course of a day. Recombinant, 1992, uses another fixed reference, a framed bas-relief, its etched lines reminiscent of the Walking Woman’s torso. Onto this marked rectangular surface are projected eighty slides. As the light image and solid surface enact a process of mutual alteration, a viewer might feel that the variations are unlimited, but the presence of the machine also suggests the ruling force of technology—how it doles out and disciplines our pleasures.

Snow’s affection for certain forms and strategies is inexhaustible, but his reprises are neither sentimental nor purely retrospective—they are rigorous. Reuse of a theme or a motif transforms it both in its physical properties and in the mind of the spectator.

Directing Attention

The Walking Woman initially drew attention to itself but very quickly began to direct attention to its surroundings as an object famed for its production of art experience. Creating objects that functioned as directors of attention continued to preoccupy Snow, as he tested his ideas in different materials and media. Films that explore different camera movements, from the obsessive zoom of Wavelength, 1966–67, to the hyperactivated machine of La Région Centrale, 1971, heighten one’s consciousness of human vision.

His sculptures are also noteworthy in this respect, many functioning as instruments, frames, windows, or apertures that open one world onto another and concentrate the power of sight. In the late 1960s Snow was working with aluminum, wood, and other sorts of industrial materials to create work at an arresting scale, but these objects were not intended for disinterested contemplation—they were made for active use. His Scope, 1967, made of stainless steel, is a giant recumbent periscope, designed for curious visitors to look through. By contrast, his hieratic Seated Sculpture, 1982, formed from the bending of three steel plates, creates a shadowy experience of tunnel vision for spectators who physically enter the work. Blind, 1968, and De La, 1972, are also directors of attention, though in different ways.

In Blind, visitors walk the narrow corridors between the sculpture’s mesh screens; their short walks bring out the characteristics of the piece, their bodies become part of the work for those looking on. In De La, spectators who approach the camera-activating machine are likely to be caught on video; here again their brief appearances become part of the work for themselves and others. Snow is not a social artist, but these works, and the many others that encourage cooperative exploration, direct his audience’s attention to the visual habits and social performances of people who go to art galleries.

Anticipating Chance

Chance factors into any creative process. Snow has sometimes courted its possibilities in his recording-media works: photographic, film, sound, and video production. This began with Four to Five, 1962, when he took his Walking Woman figure out of the studio to be photographed among pedestrians on the Toronto streets. A more carefully planned project than Snow’s film Wavelength could scarcely be imagined, but the uncontrolled flow of city traffic outside his studio windows is not insignificant to the work. Nature performs itself in his monumental landscape film La Région Centrale. Street life as it happens is the basis of his video installation The Corner of Braque and Picasso Streets, 2009, in which the real-time streaming of a surveillance camera turns Cubist when projected on an arrangement of plinths.

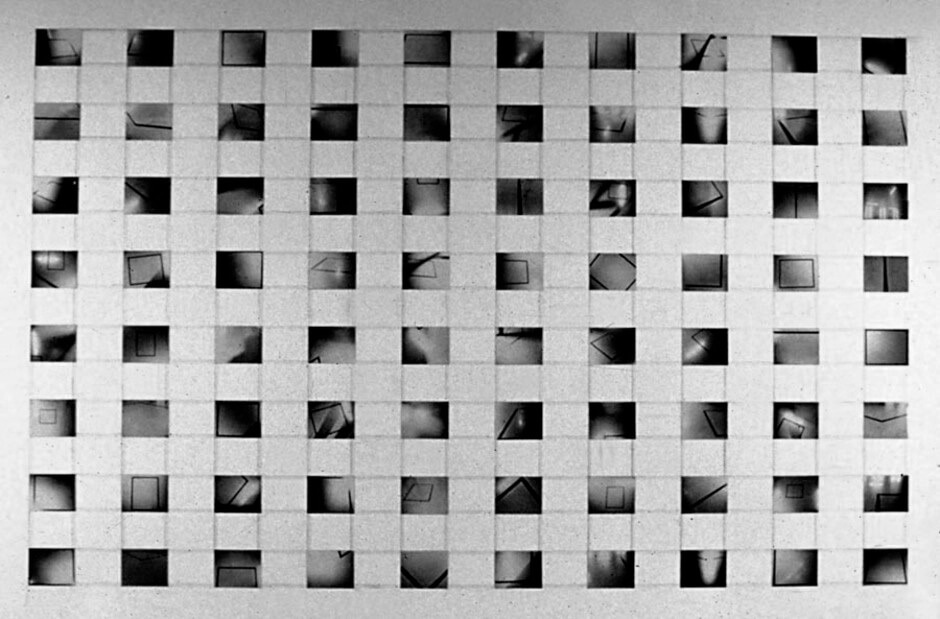

Chance also comes into play in ways that may not be recognized by the spectator. A photographic work, 8 x 10, 1969, is composed of eighty photographs of one subject: a rectangle made of black tape laid down on a silvery-grey surface. The proportions of the taped rectangle match those of the photograph (the industrial standard 8 x 10 inches). The photographs are organized in a grid (of 8 x 10), thereby forming a network of formal relationships. The hidden surprise is that these relationships, however effective, are not fixed, as the photographs are supposed to be shuffled before each installation, whether by Snow or by technicians following his instructions. This deployment of chance in an otherwise rigorous system is 8 x 10’s secret. Snow’s oeuvre is sewn with little secrets.

Materialities, Thick and Thin

From his earliest activity as a painter, Snow was intrigued with the thinness of the medium, as a kind of skin on the canvas. How thin might a medium become? As a sculptor, photographer, and filmmaker, he found the answer in light, experimenting with coloured gels and transluscent plastics, which he used as windows (the viewer looking through) or filters (light passing through), both methods altering reality. Materials are interesting in their own right, but they are also deployed by artists and filmmakers to create illusions. Snow’s work brings together the apparatuses of art and cinema: the relationship of the picture plane and the projected image to the wall; the slide or film projector and the paint spray can.

These interests are met in Two Sides to Every Story, 1974, an installation consisting of two 16mm films projected simultaneously by two projectors on an aluminum screen. The film was shot by two cameras from opposite sides of a clear plastic sheet of the same dimensions as the projection screen. The figure of a woman moves back and forth along the axis formed by the two cameras, holding up sheets of coloured card, according to the instructions of the director who is seated within the frame. The figure eventually spray paints the clear plastic sheet, making it opaque, which changes the projection screen from a “window” to a “wall,” before she slices it in half and passes through to the other side.

Puzzles and Pleasures

Dualities are present throughout Snow’s oeuvre: a painting is a free-standing presence; a sculpture is a window that the viewer looks through; a magisterial landscape view is unforgettable in part because it is shown to be constantly changing. Designed to interconnect, these systems can be difficult to pick apart and explain. Such complexities might be considered an “issue,” and Snow’s cinematic work is often quite challenging, but he has also translated his key themes—light, materiality, re-presentation, and so on—into DVD installations and public sculptures that appeal directly to the senses. Encounters with these works generate surprise, enjoyment, and enduring affection across the spectrum of audiences.

Consider Two Sides to Every Story, a work already mentioned for its dual nature as thick and thin. With projectors aimed at both sides of the hanging screen, viewers can often be found at the edges of the screen, trying to watch both sides at once. Snow’s very amusing video installation Serve, Deserve, 2009, is, as he writes, “a temporal work made for an ambulatory audience … built on an exaggerated (!) imitation of the customary restaurant situation where one waits for the waiter to bring the order. But, in this case, the projection beam delivers the food to the representation of ‘tabletop,’ tablecloth surface, in the process making a canvas of it.” What really makes the canvas both abstract and expressive is the “action painting” of an invisible waiter who overfills the glasses and flings the food onto and over the edges of the plates. And further enlivening the experience is the disappearance of the food and drink as this inept service is replayed in reverse. Strangers meeting at the edge of the projection surface “table” encourage each other to “wait for it” as the water pools, the wine flows, the salad flutters, and the pasta splats. Relationships form.

About the Author

About the Author

Download PDF

Download PDF

Credits

Credits