Sleeve 1965

Michael Snow, Sleeve, 1965

Oil, canvas, wood, 366 x 366 x 305 cm

Vancouver Art Gallery

First exhibited in December 1965 at the Poindexter Gallery in New York, Sleeve is an assemblage of Walking Woman treatments in different media and materials: paint (including spray enamel), wood, vinyl, Masonite, acetate, photograph, canvas, polyethylene, and Plexiglas. Twelve separate elements are organized in planned relationships, so that the work is now referred to as an installation. This work demonstrates Snow’s use of the form in an instrumental, conceptual, and representational framework that blazes the path to his more abstract perceptual themes.

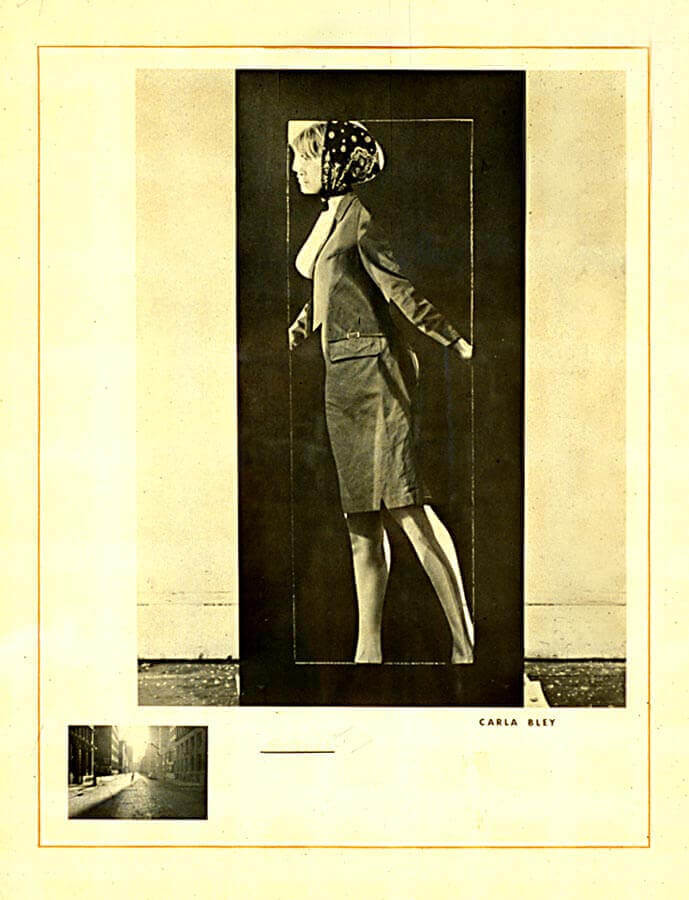

Sleeve exhibits a variety of approaches to the form: it realizes many of Snow’s ambitions for the project, as outlined in his brilliant prospectus of 1962–63, “A Lot of Near Mrs.” Three years later the form had become Snow’s “trademark.” He had made the rules for its usage, and he felt very free to break them. The figure appears in different sizes. In one variation she is curvaceous, fully modelled. In another, a real woman is stepping into the cut-out; she is a fellow musician, the American jazz composer and performer Carla Bley. Her split-second performance for the camera nests one representation in another—a compressed version of the Russian doll. In “A Lot of Near Mrs.” Snow writes, “It was not designed for uses which could be foreseen.”

Sleeve, with its framing device for a coloured gel—a standing stone with a window—made the figure into something that could be altered by spectatorial performance, by a glance through a coloured pane. The spectator could “make light of the figure.” Snow, who had already produced his Walking Woman film New York Eye and Ear Control, 1964, considered the use of spray enamels as another means of projection. Rigorously conceived, Sleeve also gives evidence of an artist crossing boundaries while respecting the perimeter of the white box.

The Walking Woman’s leading historian, Louise Dompierre, reckons that between 1961 and 1967 Snow made some two hundred individual Walking Woman works, as well as a vast number (later estimated by Snow at around eight hundred) of “site-specific” or what he called “lost” works. This was a play on the “found objects” of Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968)—Duchamp being a major influence on Snow’s and his generation’s thinking. The fugitive lives of these non-gallery pieces are documented in Snow’s Biographie of the Walking Woman / de la femme qui marche, 1961–1967(2004): the Walking Woman can be spotted at subway entrances, on hoardings; in newspaper ads and appropriated graphics; screened on banners and T-shirts; crafted as jewellery and needlepoint cushions; cut into cookies and other comestibles; as a trademark, licensed, and also liberated by the artist to turn up anywhere. As indeed it did in Snow’s subsequent production, making the conventional end-date of the series (1967) somewhat premature. The artist’s book Biographie is a case in point, but the Walking Woman is also an active agent in Snow’s 2002 film *Corpus Callosum.

About the Author

About the Author

Download PDF

Download PDF

Credits

Credits