Maud Lewis’s origins as a painter lie in her childhood home, and she only ever had one teacher, her mother, Agnes. She began to paint as a way to contribute to the household income, first with her parents and then with her husband. She never went to an art gallery or museum; her influences were commercial imagery from greeting cards, advertisements, tourism promotion, and mass-produced prints by such firms as Currier and Ives. Still, Lewis was more of a leader than a follower. Her work does not look like that of any other artist—but the work of many other folk artists certainly reflects her influence.

A Style of Her Own

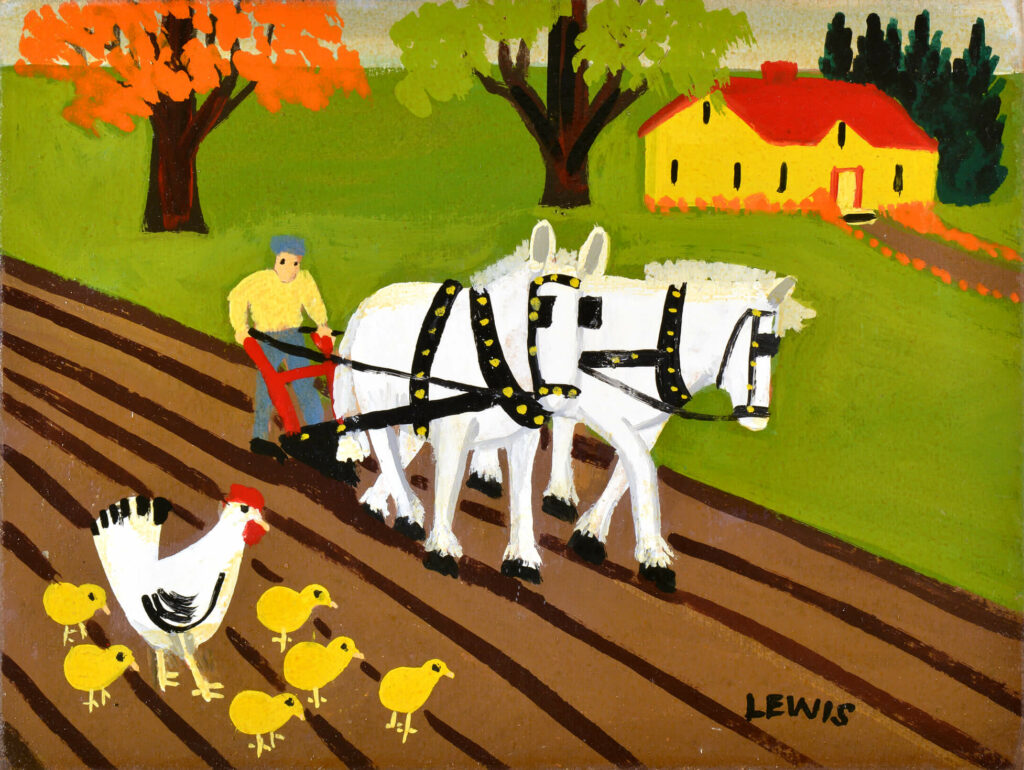

It is the physical challenges that Maud Lewis met, and the way that she was able to create a personal artistic vision despite them, that has always been at the root of Lewis’s enduring popularity and the public fascination with her life and work. She devised a unique and immediately recognizable style―Untitled (Horses Ploughing), n.d., is a typical example of one of her bright rural scenes. She made paintings that, with their vivid colours and simple forms, convey joy and optimism to their viewers, and she did so while enduring, and overcoming, what for most of us would have been crippling challenges.

Lewis’s paintings are often described as being without shadows. This statement dates back to the Star Weekly feature about her, written by Murray Barnard, in which he says that Lewis’s work “glows with a simplicity that is suited to the rural scene―no shades or shadows.” That theme was taken up in a completely straight manner by Diane Beaudry in her 1976 documentary for the National Film Board, Maud Lewis: A World Without Shadows. In the introduction to Beaudry’s film Lewis’s art is described as taking the viewer back to the world of childhood, one “without shadows.” Lance Woolaver, however, in his stage play A World Without Shadows, uses the same title in an ironic way, suggesting that as bright and happy as the paintings are, Lewis’s life was certainly rife with shadow.

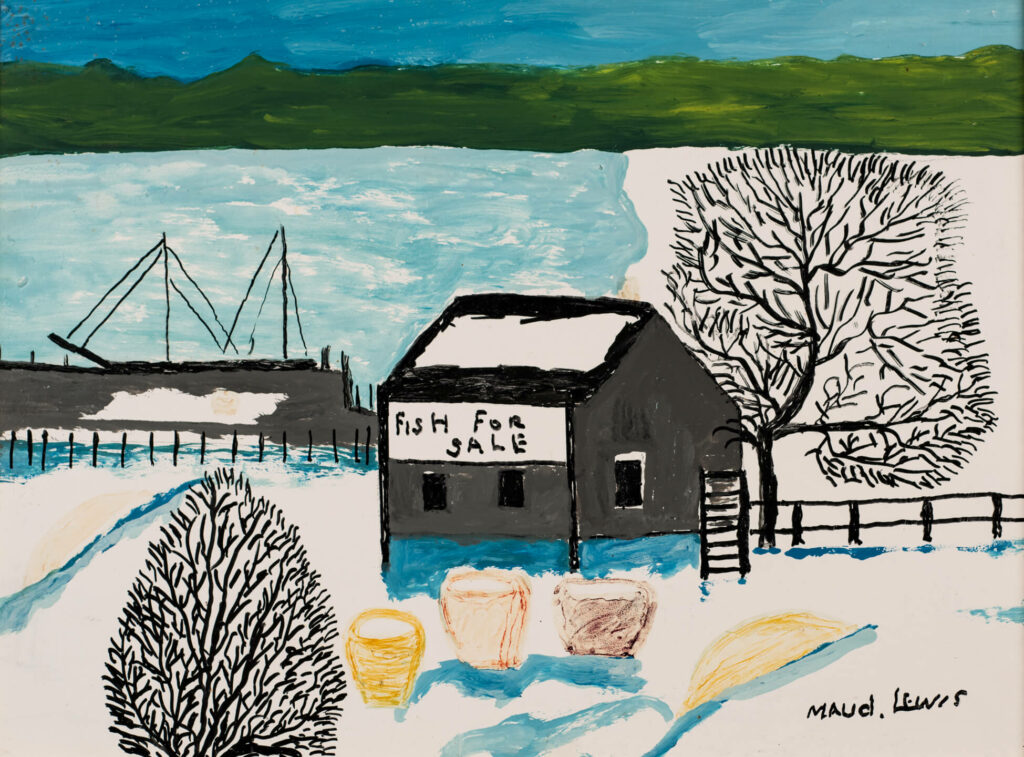

In looking at the works we see it is true that few have shadows painted in, though by no means are they completely absent. In her snow scenes, for instance, she often included blue shades that suggest shadows in the snow and give a sense of depth to the compositions, as can be seen in Horse and Sleigh, 1960s. In an untitled painting from the early 1960s of a fishing schooner tied up to a wharf at low tide, the shadow of the boat stretches across the mud flat, and in Fish for Sale, 1969/70, the small building casts a shadow in front of it.

Another Nova Scotia painter, Alex Colville (1920–2013), has a reputation for painting without shadow. His work is a polar opposite to that of Lewis, of course, solidly rooted in Western art history as it is, as opposed to vernacular folk art, but shadows play a part in his reputation as well. He rarely painted them: in a work such as Ocean Limited, 1962, the walking figure seems to almost float above the ground. Nonetheless, in Colville’s painted world the shadow of chaos is always looming, just outside the picture plane. Colville served as a war artist in the Second World War and recorded both the day-to-day lives of soldiers and sailors, and the horrific results of war. He was present at the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, an experience that profoundly influenced his future art. Colville’s day-to-day life was more comfortable and secure than Lewis’s, but it is her painted world that remains innocent, unlike his more sombre one of experience.

Necessity Driving Invention

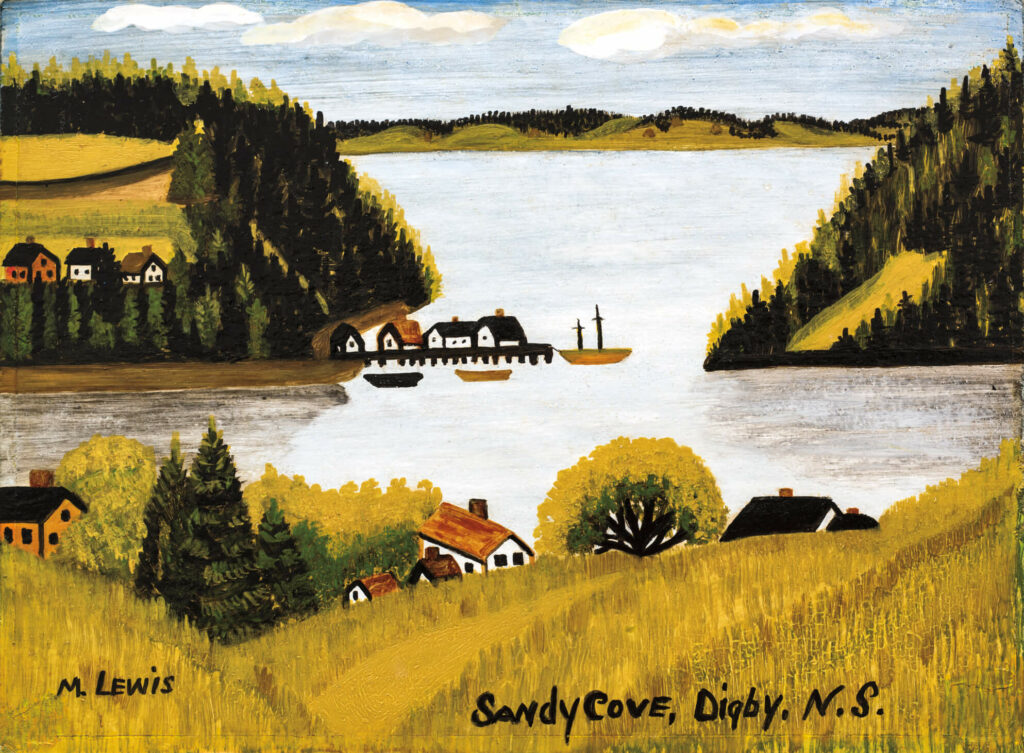

Perhaps the most telling influence on Maud Lewis was her arthritis and the way that it progressively attacked her physical abilities. Over her lifetime she lost most of the capacity to open her hands, and had little or no dexterity in her fingers. Her work changed as she aged because she was incapable of the finer details that she once had been able to approach, if not completely master. One need only compare an early painting such as Sandy Cove, late 1940s/early 1950s, to examples of her later work, such as Scene Near Bear River, 1960s, to see the difference in line quality and paint handling.

She started all of her paintings by drawing the outlines of the composition. Once the design was set, she worked with small brushes, propping her right hand on her left arm and laboriously filling in the outlines with colour. She used sardine tins and tobacco can lids to hold her paints, and she often worked directly from the can or, in later years, the tube. She would mix individual colours in their own tins, rather than using a palette. Her paintings can seem to be blocks of solid colours, but they actually display varying tones and shades, which she used to create a sense of space.

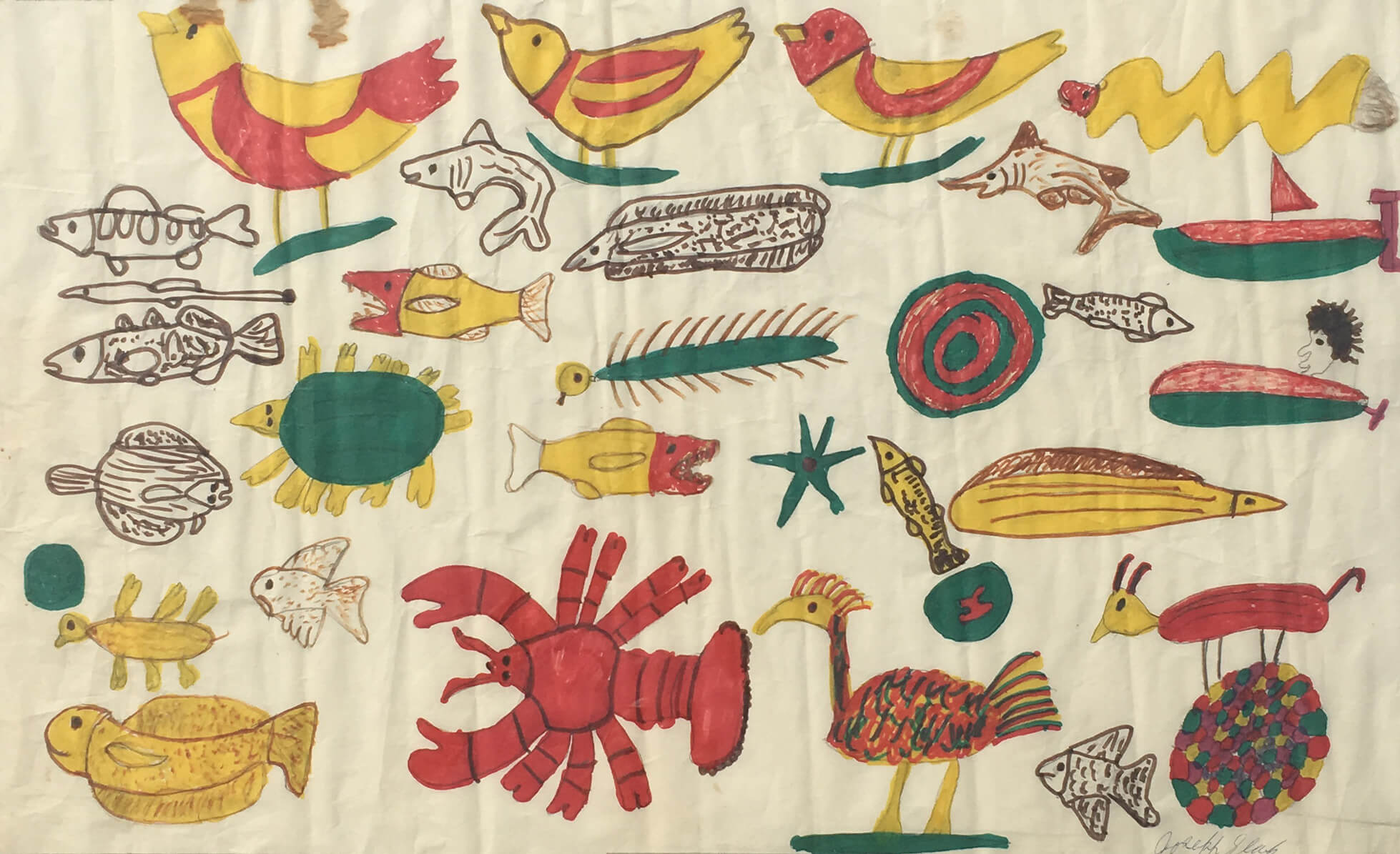

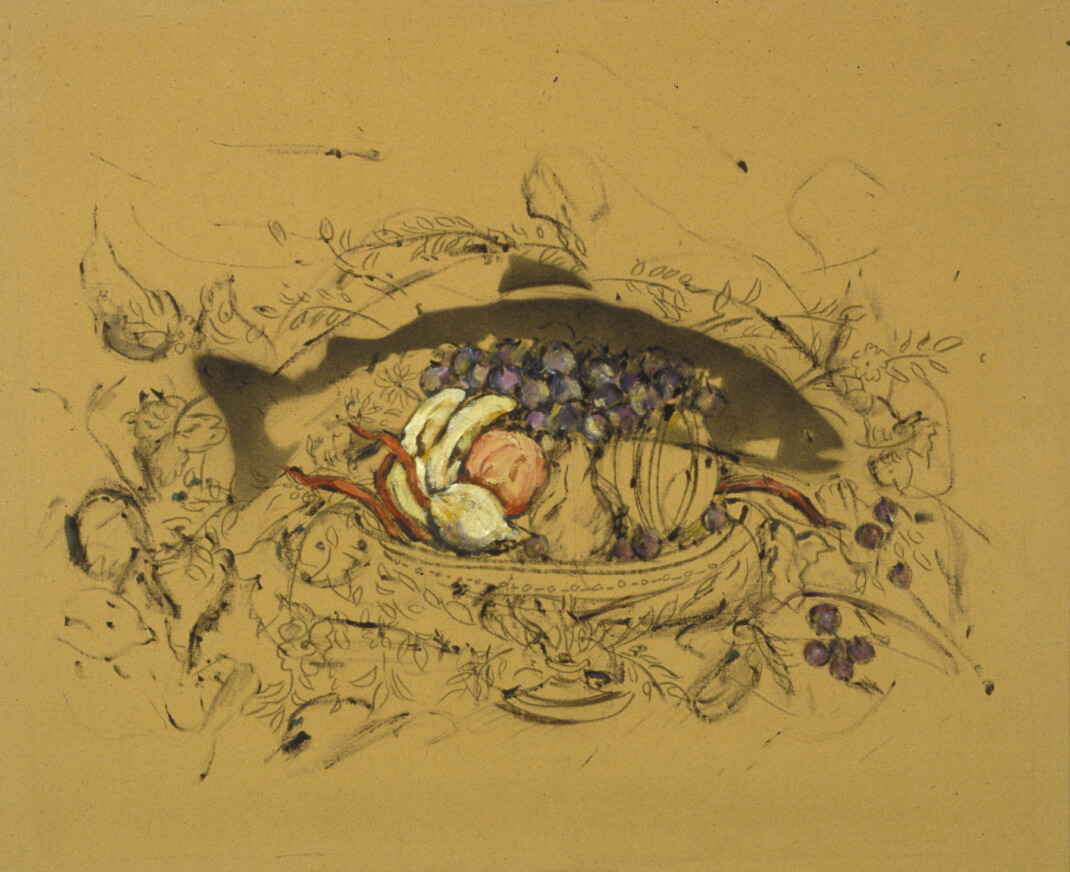

By the 1960s these outlines were often made with stencils, cut from cardboard by Everett to assist her as her arthritis progressed. Lewis’s use of stencils, which sped up the process and allowed her to keep up with the demand for her work, was mirrored by the practice of another renowned Nova Scotia folk artist, Joe Sleep (1914–1978). His drawings, which featured cats, birds, fish, and other animals, were all produced using stencils for the central images, as can be seen in Untitled [Animals], n.d. The use of stencils was common in vernacular decorative art in Nova Scotia throughout the nineteenth and earlier twentieth century. Conceptual artist Gerald Ferguson (1937–2009), an early supporter of Sleep and one of the most important figures in the institutional and critical attention paid to Nova Scotia Folk Art from the 1970s, often worked with stencils in making folk-art-inspired paintings in the 1990s, a technique that is evident in Still Life with Bowl, Fish, and Fruit, 1989.

Portraits of Nature

Maud Lewis’s painted world depicts people living closely with nature, with the flora and fauna that share their day-to-day lives. Animals often appear in her paintings as part of the overall composition, usually in her scenes of rural life: dogs gambol beside carriages or follow children as they play; horses pull carts, wagons, and carriages; cows stand quietly in the fields or wander onto the roads; chickens peck in the foreground of a picture; yoked oxen haul logs or wagons; and birds wheel in the sky above all this activity. The only woodland creatures that she depicted regularly were deer, often pairing a doe and fawn―as in Fall Scene with Deer, c.1950―who usually are looking out from the picture at the viewer. Animals are part and parcel of the world of Maud Lewis, and few of her pictures lack them.

-

Maud Lewis, Fall Scene with Deer, c.1950

Oil on pulpboard, 29.5 x 34.9 cm

Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax

-

Maud Lewis, Team of Oxen in Winter, 1967

Oil over graphite on pulpboard, 28.9 x 34.1 cm

Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax

-

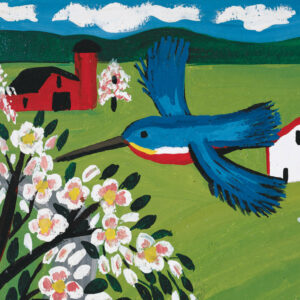

Maud Lewis, British Kingfisher & Apple Blossoms, 1963

Oil on pulpboard, 23.0 x 30.2 cm

Private collection

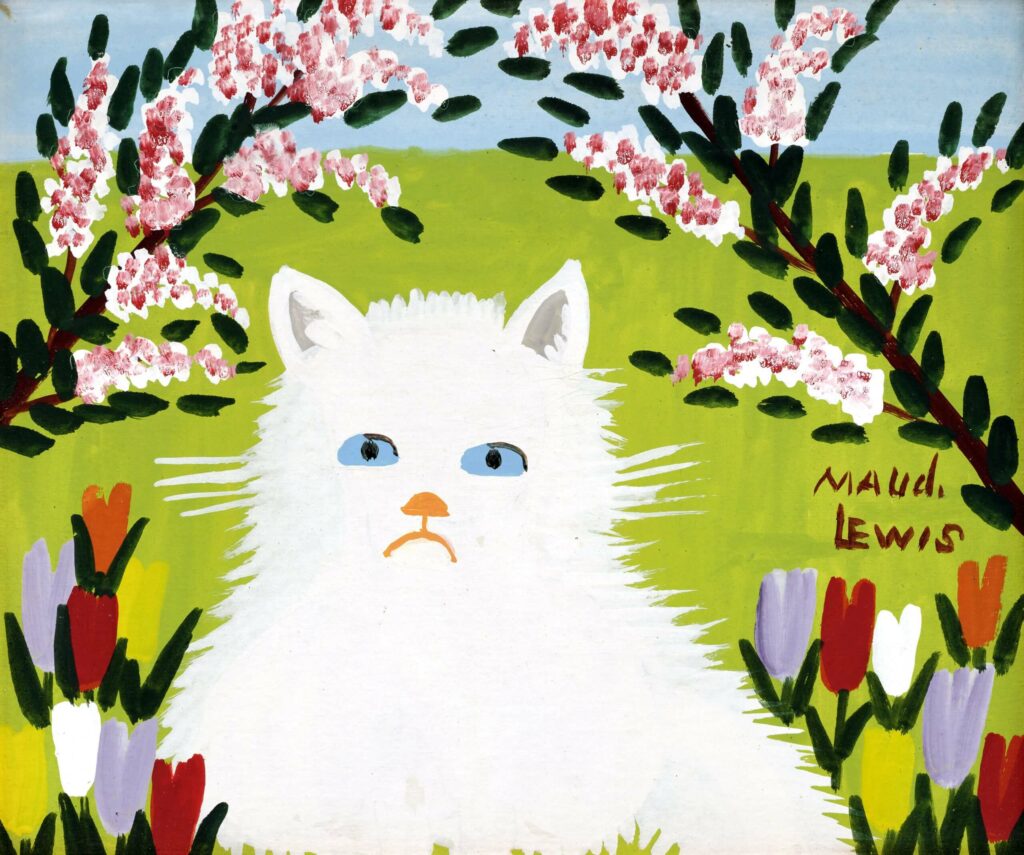

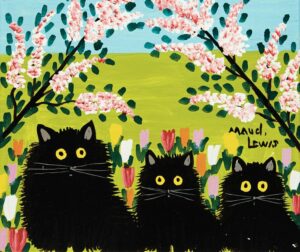

In her later paintings Lewis developed a style of presenting animals almost as portraits—frontal views, often of cats and oxen, sitting in shallow space and looking straight out of the picture at the viewer. Her oxen, in particular, are noteworthy for their long lashes and brightly decorated harnesses. As befits a harness maker’s daughter, in works such as Team of Oxen in Winter, 1967, she shows the proper rigging and the Nova Scotia–style yoke—a head yoke that sits just behind the oxen’s horns. Her cats, often a mother cat and a kitten or two, were among her most popular images. Long-haired and yellow-eyed, usually black, they are often depicted sitting against a bed of flowers.

When Lewis painted birds, it was usually in a more decorative manner, such as could be seen on wallpaper, or trims and borders on walls and furniture. This approach was more aligned with traditional folk art, which tended to embellish common household goods. A familiar theme for Lewis in her painted house and decorated objects, as well as in her stand-alone paintings, was the theme of song birds flying amidst flowering branches or bunches of wildflowers. The compositions were usually overall floral patterns, again akin to wallpaper decoration, within which the birds were depicted perching. The compositions were flat, with nothing seen beyond the first layer of flowers or branches. Her paintings of birds in branches in bloom were not among her most popular compositions, but her love for them was apparent in how much they were used in her decoration of her house. She occasionally painted birds in other scenes, such as British Kingfisher & Apple Blossoms, 1963, a work inspired by an image on a Peek Freans biscuit tin.

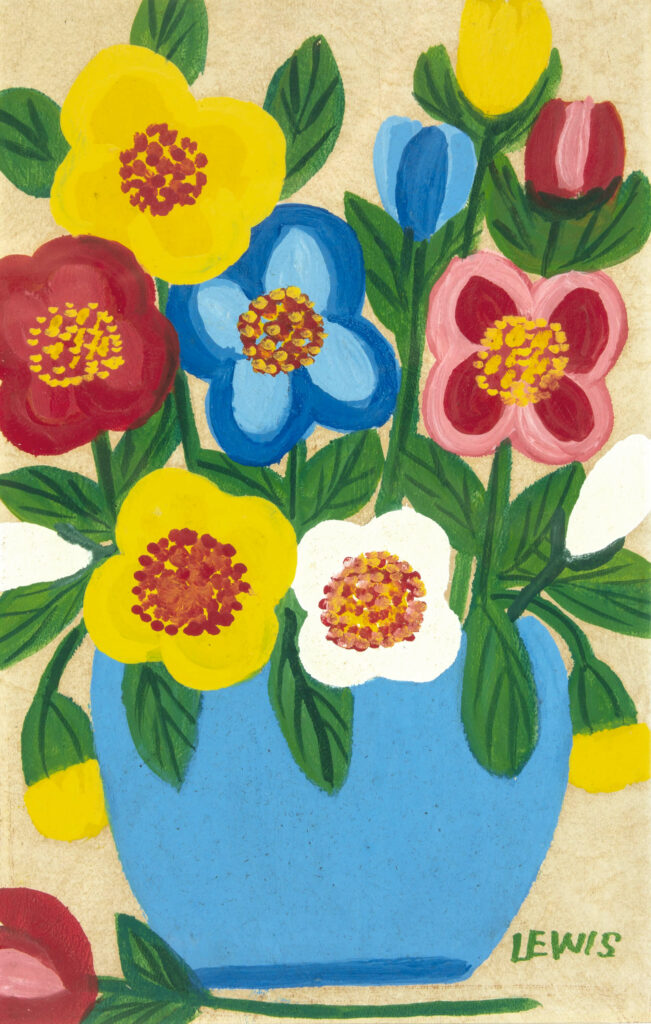

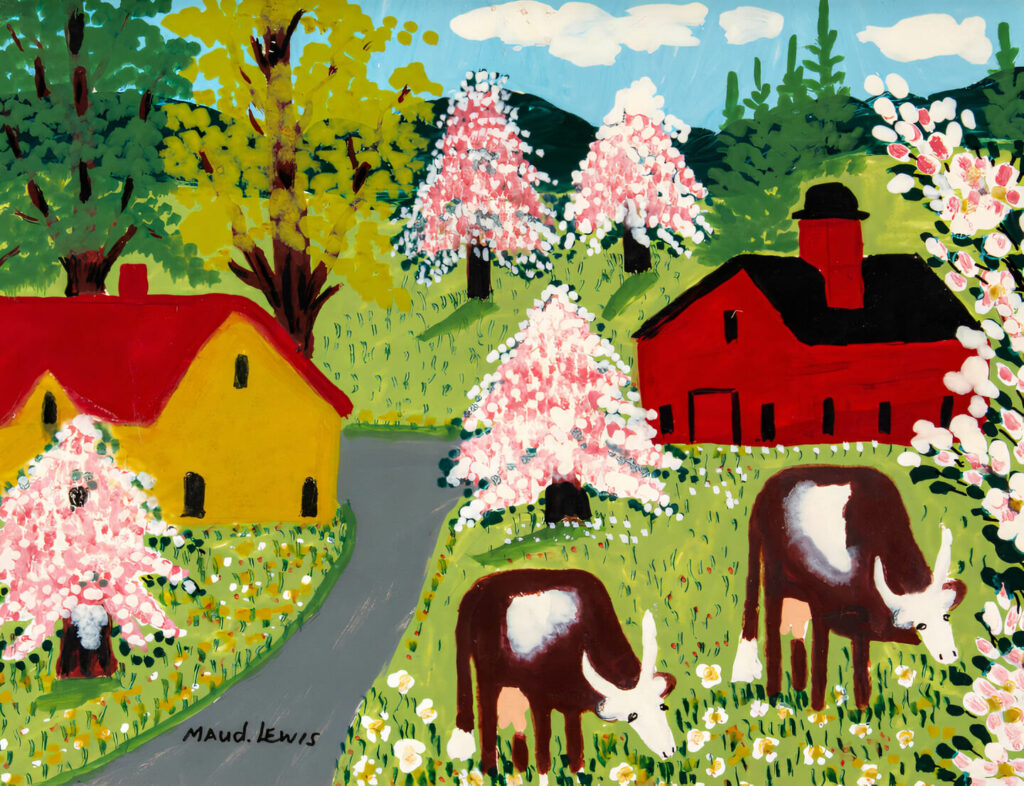

That Lewis loved flowers is also apparent from her work. She painted them on several surfaces and objects in her house, and she included them in many of her paintings. She was even known to add flowers to plants that do not have them—a stand of spruce trees in blossom, for example, as in Cows Grazing Among Flowering Spruce, c.1965. Much as she used fall colours in snowy landscapes, she was not one to let the facts get in the way of a good story—or painting. Lewis painted sweet peas, which grew around the house (and sprigs of which Everett would present to customers in season), roses, apple blossoms, and, most famously, tulips. That the world of her art was so often in full bloom is one of the enduring pleasures of Lewis’s work—and certainly a large part of the tone of hope and happiness that so many viewers find there.

At Work and Play in Nova Scotia

Maud Lewis depicted many aspects of day-to-day life in rural Nova Scotia in her paintings. In her images we see farmers working the fields, plowing, sowing, and harvesting. Heavily loaded wagons of logs show the results of the lumber industry. Trees are tapped for maple syrup, a blacksmith works at his forge, and a fisher repairs his nets. But life is not all work—in Lewis’s scenes of Nova Scotia we see sleighing parties, Sunday drives in the countryside in carriages and antique motor cars, skiing, fishing, and sailing.

-

Maud Lewis, Maple Syrup Gathering, 1960s

Oil on board, 28.6 x 33.3 cm

Collection of CFFI Ventures Inc. as collected by John Risley

-

Maud Lewis, Drying Cod Flakes, mid/late 1950s

Oil on pulpboard, 32 x 34.8 cm

Private collection

-

Maud Lewis, Children Skiing, mid 1960s

Oil on pulpboard, 31.8 x 35.0 cm

Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax

-

Maud Lewis, Eddie Barnes & Ed Murphy Going Fishing, 1965

Oil on pulpboard, 32 x 36 cm

Private collection

What we do not see is life in the towns or cities, views of the shops on the main street of Yarmouth, or the busy and crowded wharves at Digby. Instead, we view small villages, single farms, and quiet coves with one or two fishing boats tied up at the pier. It is a romantic view, a “peaceable kingdom” that we experience in Lewis’s paintings, one free from toil, where work is balanced by play, and where no one wants for anything. The opposite, then, of her actual experience of daily life.

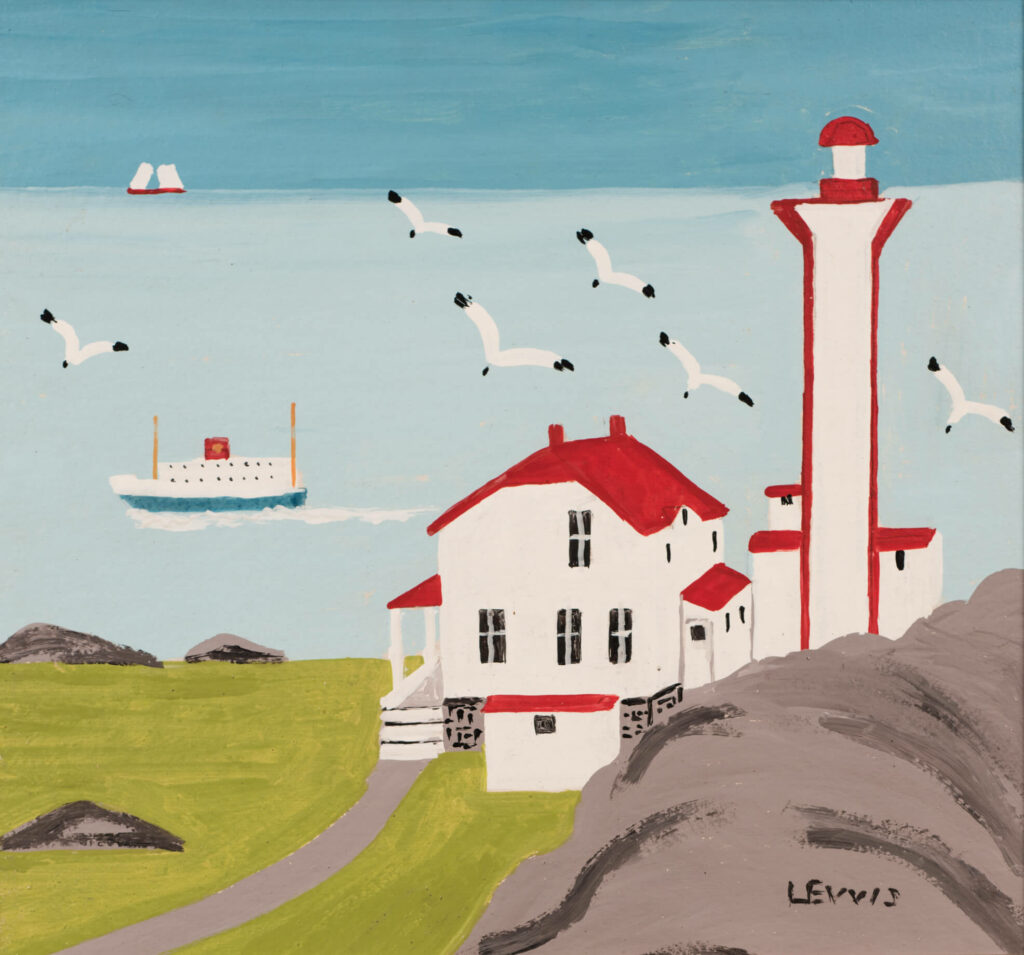

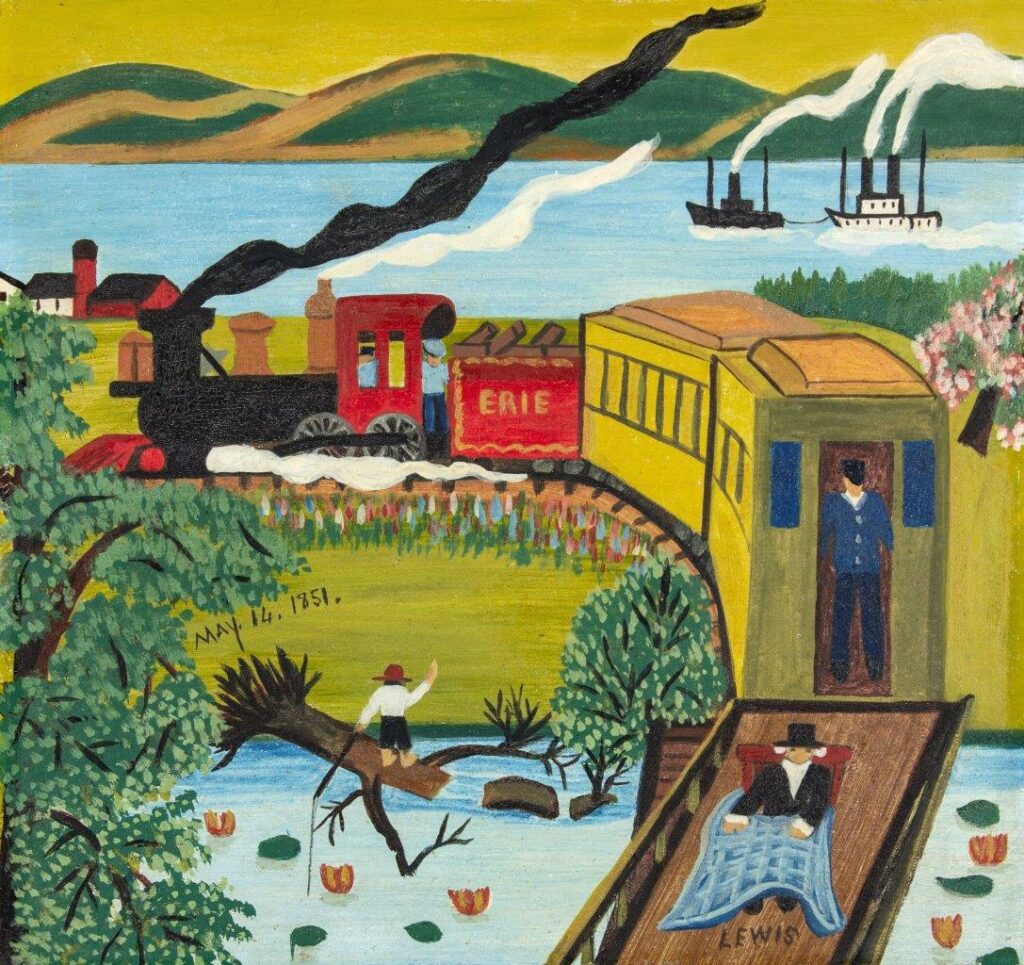

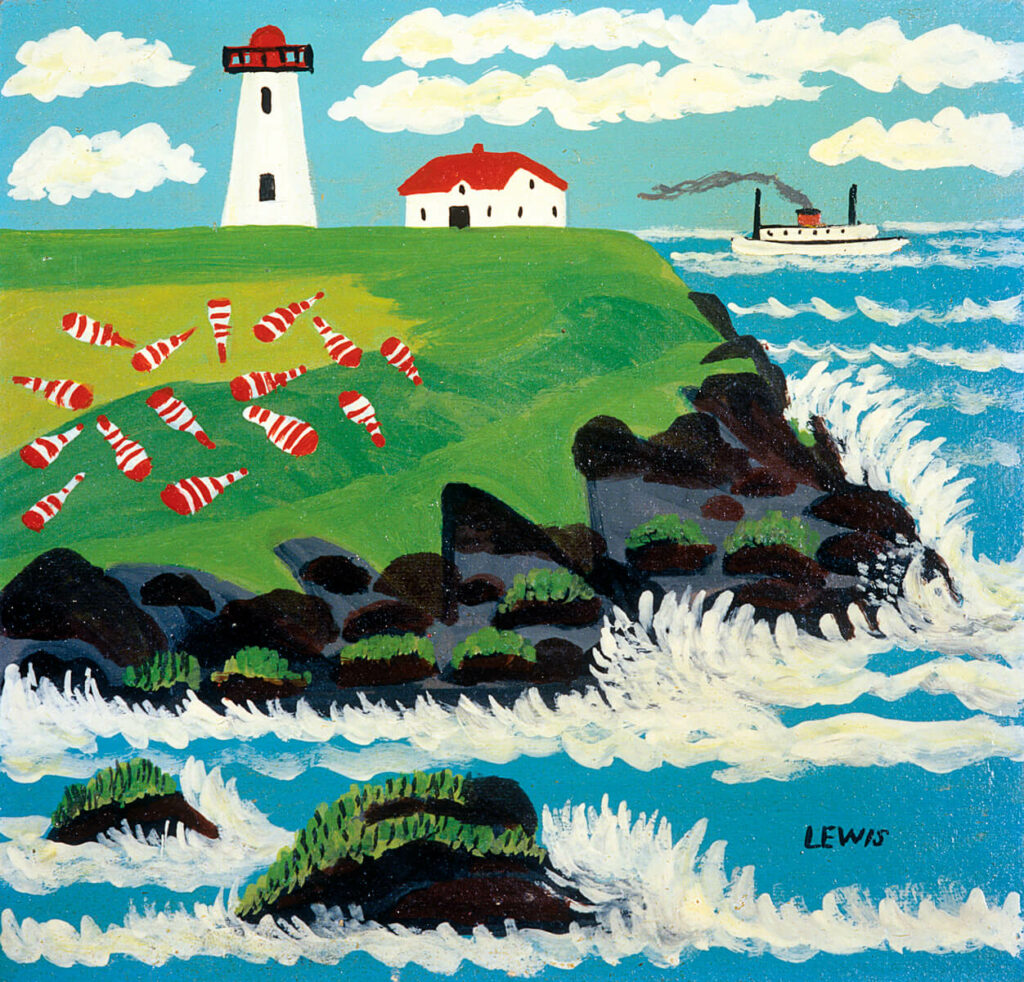

Few recognizable places populate her paintings, making the ones that are identifiable stand out all the more. The Digby and Annapolis Railroad makes an occasional appearance, as well as landmarks such as the Yarmouth lighthouse. Even Nova Scotia’s sailing ambassador, the Bluenose II, appears in one painting, although it was a commission. Lewis often depicted Cape Islander fishing boats, as well as boats and ships from the age of sail, but she rarely specified them by their actual names.

Material Considerations

The materials that any artist uses to make his or her work depend on numerous factors, most importantly on access. It is a general rule of thumb that artists will use the best materials that they can afford, and the range of quality in those materials can vary considerably over the course of their careers. Early Cubist paintings, for example, the works of Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Georges Braque (1882–1963), with their muddy brown palettes, have often been attributed as much to poverty—earth-tone oil paints were cheaper than bright colours—as they have to aesthetic decisions.

Maud Lewis was no stranger to poverty, and she used different materials for her paintings at various times. Early on, she frequently used whatever paints Everett could find for her, most often oil-based boat and house paint. Her brushes were usually of poor quality, purchased at local hardware stores, and their bristles are often found embedded in the surfaces of her paintings.

She worked on boards, cut by Everett, and she kept her panels small, both for ease of handling them more readily with her restricted mobility and for ease of sale. She made a few larger paintings as special requests, but none were much larger than two by three feet. In an article in the magazine the Atlantic Advocate from 1967, Doris McCoy writes:

Her husband patiently buys her tubes of paint from the local hardware store, and saws the one eighth inch hardboard pieces which she uses for her canvases. The size of the boards must be within a nine by twelve-inch range because of her disability. However, Mr. Lewis saws as fancy strikes him and doesn’t trouble to make the pieces a standard size, which causes not a few headaches for the art dealer when it comes time to frame the pictures.

Over the years Everett was able to find artist’s paints and materials, sometimes from tourists who left them behind. Lewis also developed a group of patrons and supporters who would help her with materials.

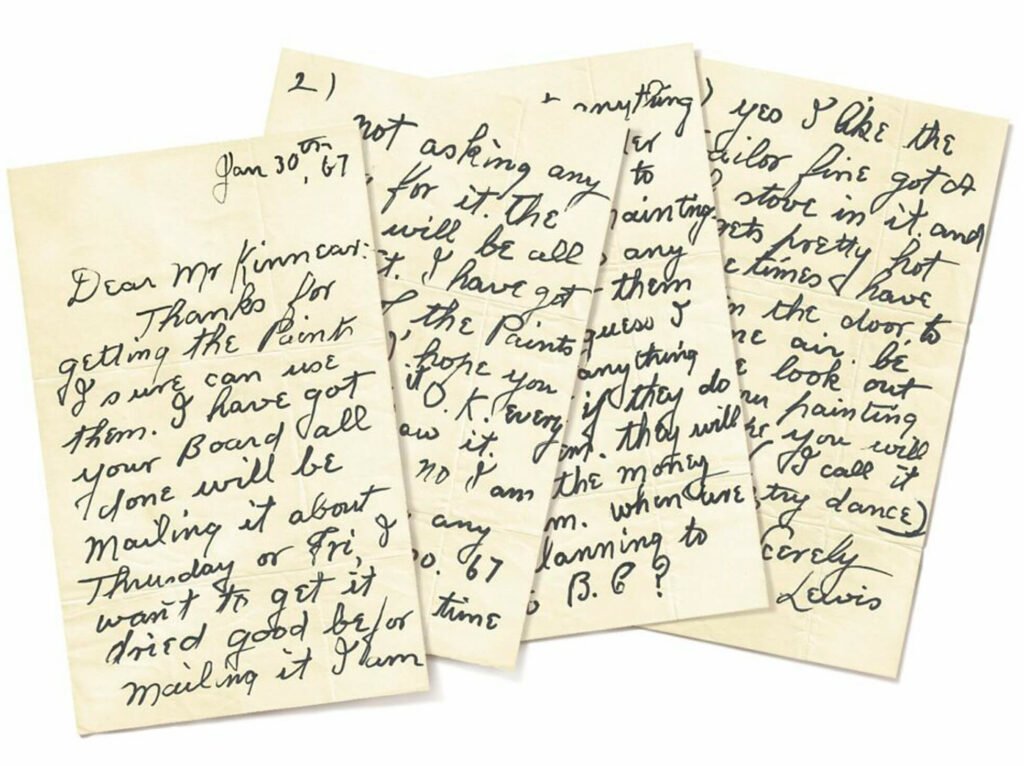

After the CBC television program about Lewis aired in 1965 and the publication of the Toronto Star Weekly story on her that same year, more people reached out to assist her. One was the London, Ontario-based painter John Kinnear (1920–2003). As his daughter recounted in an article for Canadian Art magazine, her father was struck by this story of disability, poverty, and perseverance:

As a former prisoner of war in World War II, he knew too well of pain and hardship, and he decided to help her. In the autumn of 1965, he mailed her a box of archival paints, sable brushes and standard Masonite boards, which I had primed. It was the beginning of a friendship that lasted until Lewis’s death in 1970.

Her early supporters and art dealers, Claire Stenning and Bill Ferguson, also provided materials, as did patrons such as Judge Philip Woolaver, one of her most dedicated early collectors.

After her death in 1970, there was much discussion about fake Lewis paintings that were periodically appearing in local auctions and being offered to art galleries. One of the claims put forward to ascribe authenticity to works was that Lewis painted on beaver board, a wood fibre composite, not Masonite, and thus any painting on Masonite could reliably be considered a fake. However, Kinnear had introduced Lewis to Masonite in 1965. And as Ralph McIntyre recalled in a letter to the Halifax Chronicle Herald in 1989:

For about 15 years I operated a woodworking and building supply outlet near Digby and supplied her with Masonite some of that time. Mrs. Lewis, a friend as well as a customer, did use a green backed board called beaver board. This became scarce and I suggested to her that one-eighth inch Masonite would make a better product as it was a more stable board and it would not warp or twist.

McIntyre also explained why, in Lewis’s later years, the sizes of her paintings became more consistent—at his shop they would cut the four-by-eight-foot sheets of Masonite into uniform panels—as he remembered, 9 x 16 inches to make eighteen pieces per sheet.

Ultimately, Maud Lewis developed a unique style that is instantly recognizable. Unaware of work by other artists, she developed a visual vocabulary and a way of working that, while influenced by graphic art, is wholly her own. Her works are simple, but that simplicity is hard-won―as the great modernist sculptor Constantin Brancusi (1876–1957) said, “Simplicity is not an end in art, but we arrive at simplicity in spite of ourselves as we approach the real sense of things.” Lewis’s approach was the result of her own decisions about the images she wanted to paint. She repeated many images and themes, certainly, but that takes nothing away from the achievement that the development of her style and content represent. From her little house by the side of the road, self-taught and physically isolated, mostly ignored by the larger art world, patronized when she was not, she nonetheless achieved what very few artists ever do, the creation of an authentic, consistent, and individual style. In doing so, she created a series of iconic works, and sparked a new artistic genre: Nova Scotia Folk Art.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements