Maud Lewis’s significance grew exponentially after her death, and in a way, there are three Maud Lewises: the artist, the icon, and the brand. The artist is celebrated with a permanent display of her work in Halifax and with national and international touring exhibitions. The icon is featured on Canadian stamps, is often cited as an example for people, especially children, living with physical challenges, and has been the subject of numerous books, plays, and films. As a brand, she has become a symbol of Nova Scotia, central to the story of the province that successive Nova Scotia governments and institutions have chosen to tell to the rest of the world and a central figure in the creation of Nova Scotia Folk Art as a distinct style. Critical thought on Lewis’s significance informs all three of these narratives, fuelling ever-increasing interest in her complex legacy and her deceptively simple work.

The Business of Art

Maud Lewis obviously enjoyed painting, as it was something that she had done from her childhood, when she began painting under the tutelage of her mother, Agnes (German) Dowley. But it was never simply a hobby, even in her youth. As Lewis grew older, whether from economic necessity or entrepreneurial ambition (and perhaps a mixture of the two), she and her mother turned their pastime of painting scenes into a small business, selling Christmas cards door to door in Yarmouth.

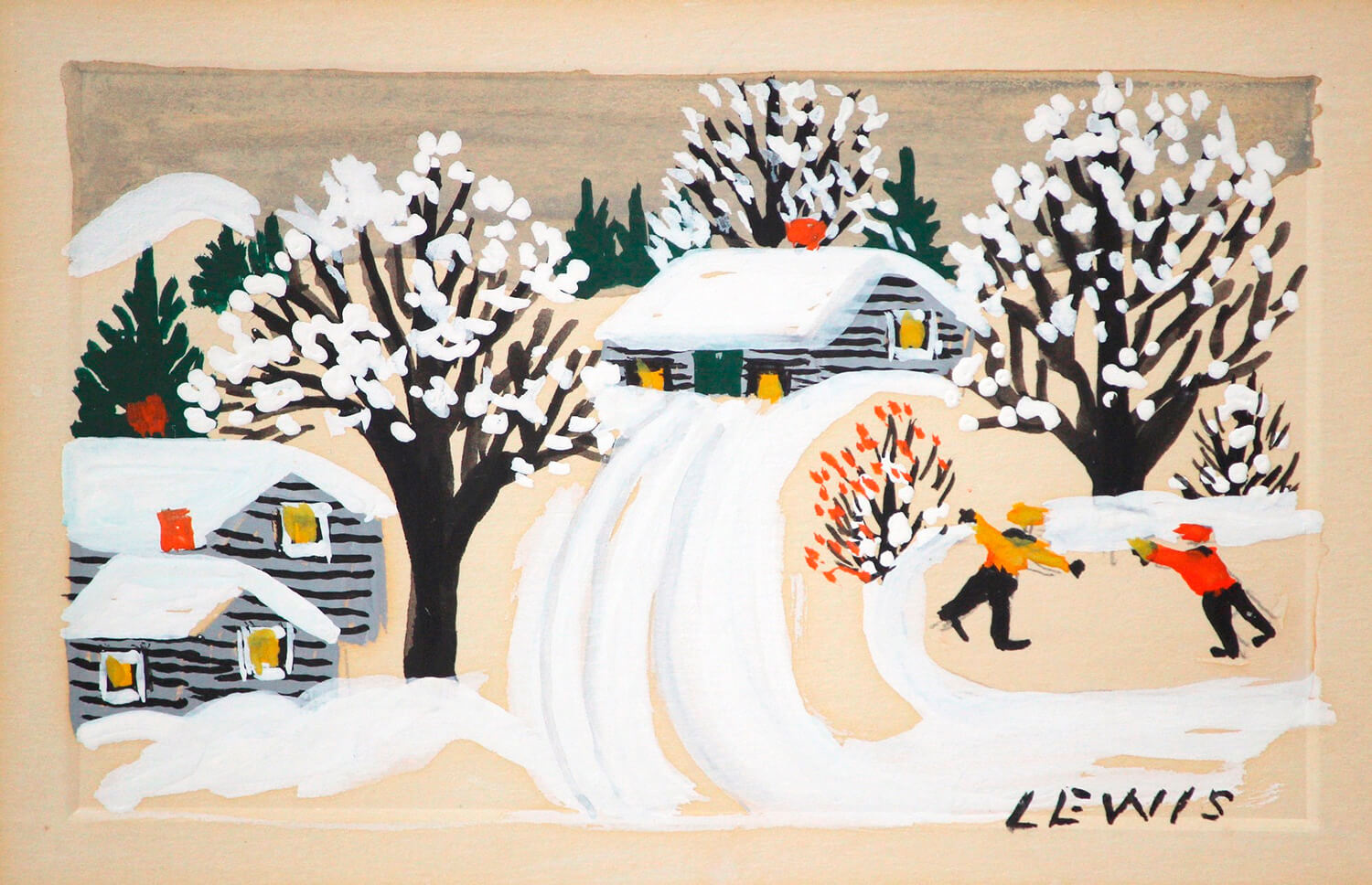

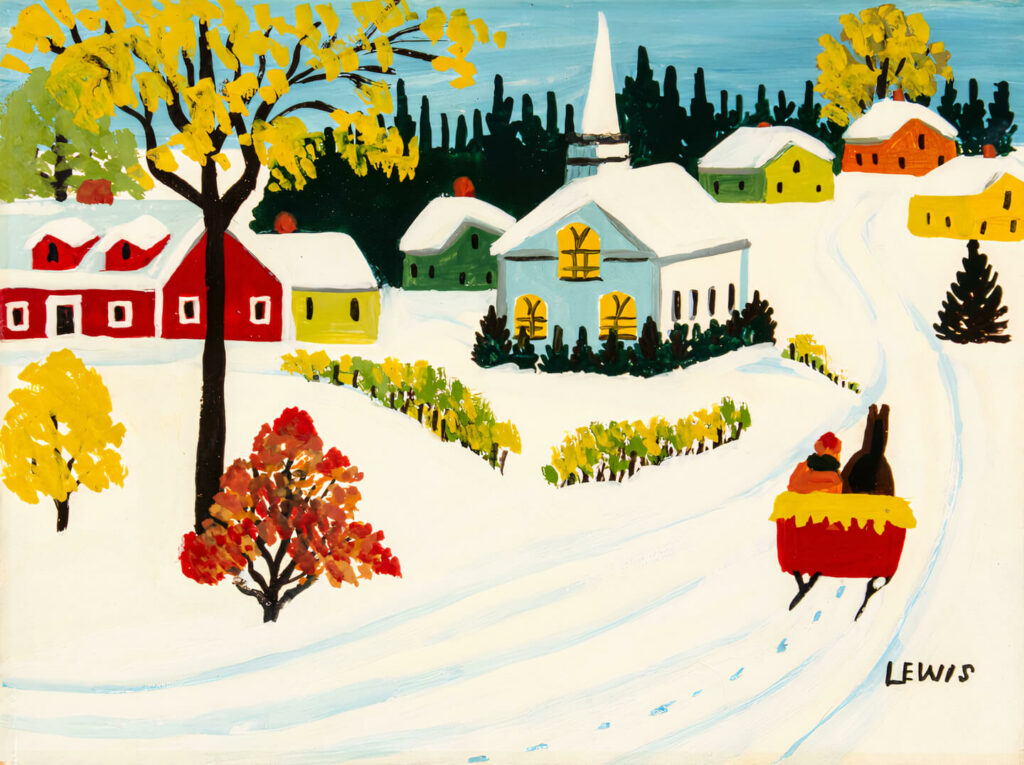

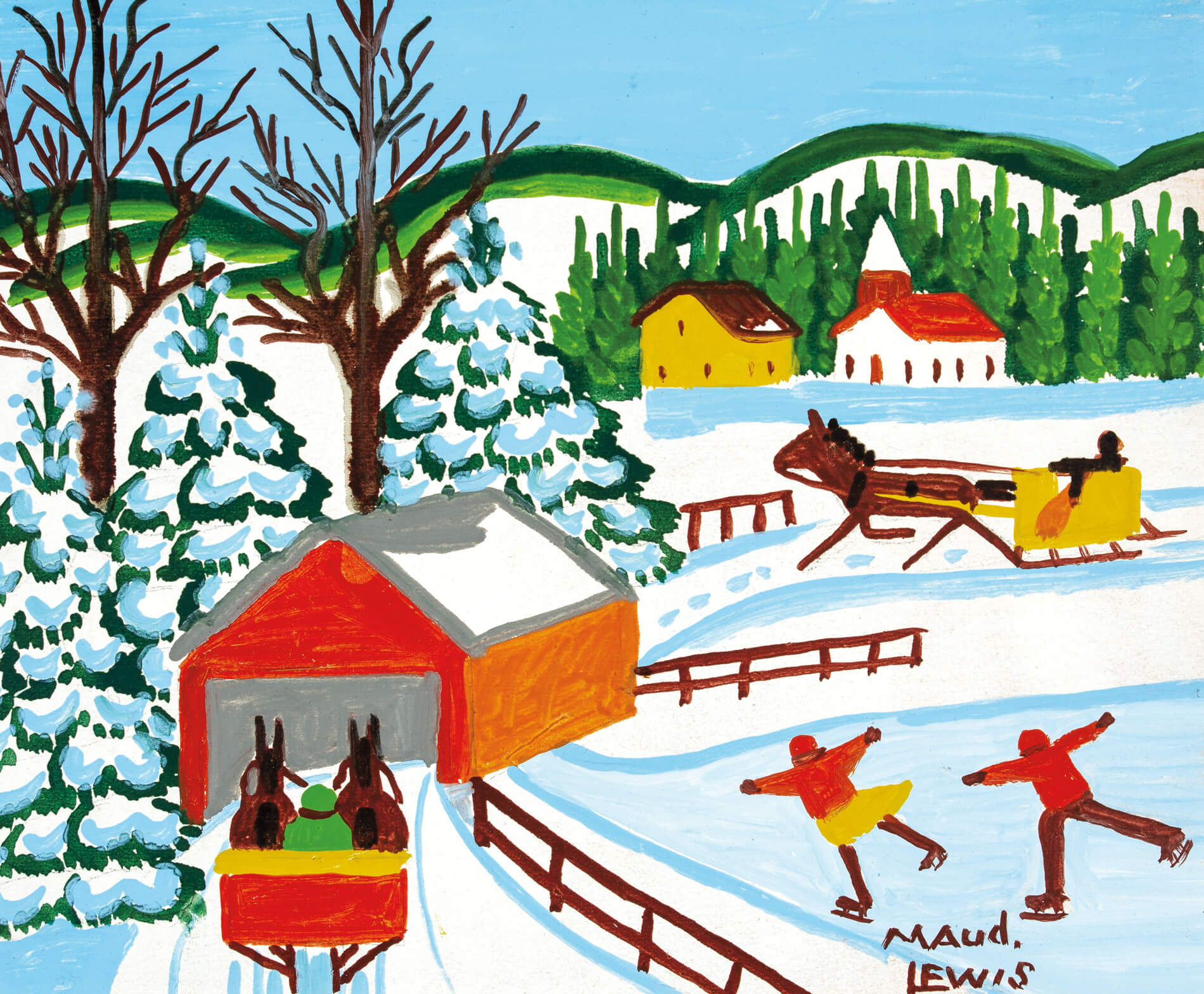

Her first commercial enterprise mirrors the content of her earliest extant paintings. Her influences were the sentimental and nostalgic imagery made popular by the greeting card industry and by the makers of mass-produced prints such as Currier and Ives. Many of the early cards and paintings are clearly her versions of existing commercial imagery. Children Waving at a Train, c.1950s, for instance, features an antique steam engine flying American flags, and her Christmas cards often feature figures in Victorian clothing. Currier and Ives prints, in particular, would have been common in the homes of Yarmouth and Digby, and depict the sorts of scenes beloved by Lewis: country churches in the snow, sleigh rides, horse-drawn carriages and wagons, small farmsteads with placid animals.

These popular genre scenes were what the public demanded, both from the commercial operations—who put them on plates, tea towels, biscuit tins, and just about any other mass-produced item imaginable—but also from the painters of the day, many of whom worked for print and advertising companies as commercial artists. For instance, J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932), Franklin Carmichael (1890–1945), Frank H. Johnston (1888–1949), Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), and F.H. Varley (1881–1969), members of Canada’s famous Group of Seven painters, worked as commercial artists for Grip Limited in Toronto, a printing house that produced imagery for advertising, package design, newspapers, and other applications.

Perhaps from her lack of formal training, or because of her reliance on commercial graphic art as source material, Lewis always deflected any description of herself as an artist. She rarely travelled, and there were no art galleries or museums locally where she would have been exposed to examples of fine art painting and drawing. In a CBC television interview in 1965 she was asked about her influences. “My favourite painting?” she said. “I’ve never seen many paintings from other artists, you know, so I wouldn’t know.” The images she would have observed would have all been the products of the commercial graphics industry, such as the calendars that can be seen festooning the walls of her house in a photograph of her and Everett from the mid-1960s. Lewis was not alone in this, of course; many twentieth-century artists had their first exposure to art through the commercial graphics industry, including Lewis’s fellow Maritimer, painter Mary Pratt (1935–2018), who acknowledged the impact of commercial graphics on her own art.

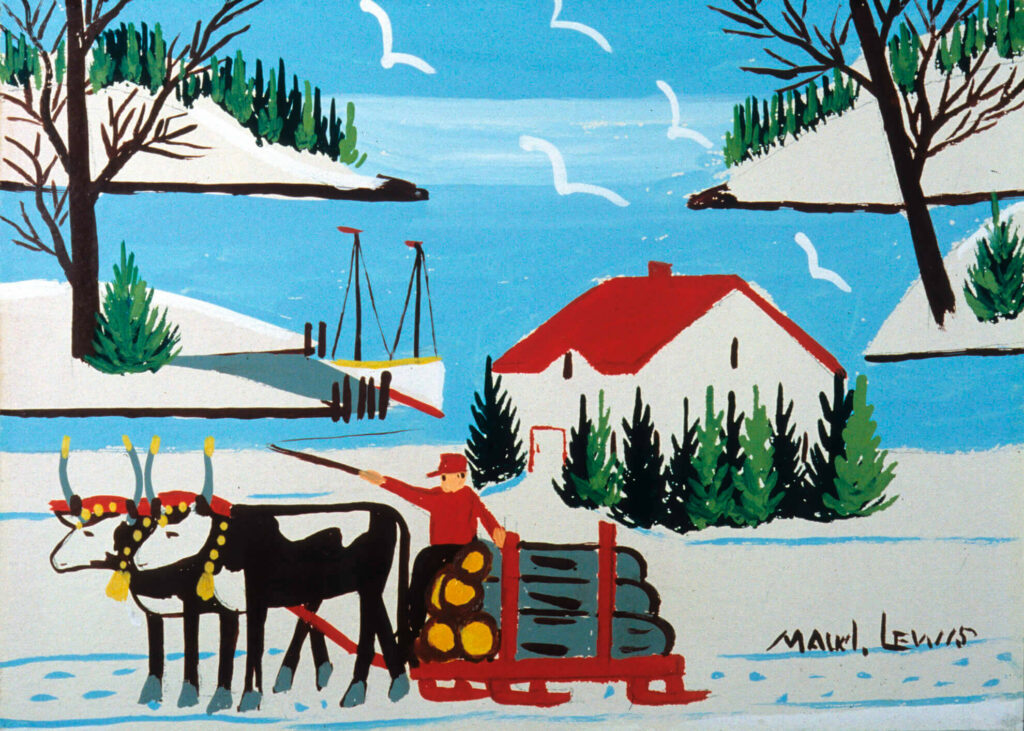

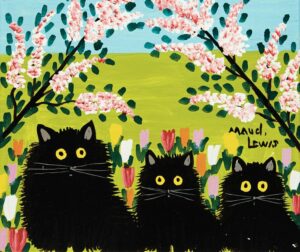

The other influence on Lewis’s work, and perhaps the deciding one, was her customers. Simply put, she responded to what the market demanded—designs for cards and images that were not selling were quickly discarded for ones that were, and she had no compunctions about repeating popular imagery. She painted dozens of pairs of oxen, for example, and perhaps hundreds of her popular family of black cats. The market, as represented by her customers’ preferences, played a part in honing her painting into what has become the recognizable Maud Lewis style.

Painting an Idyllic Past

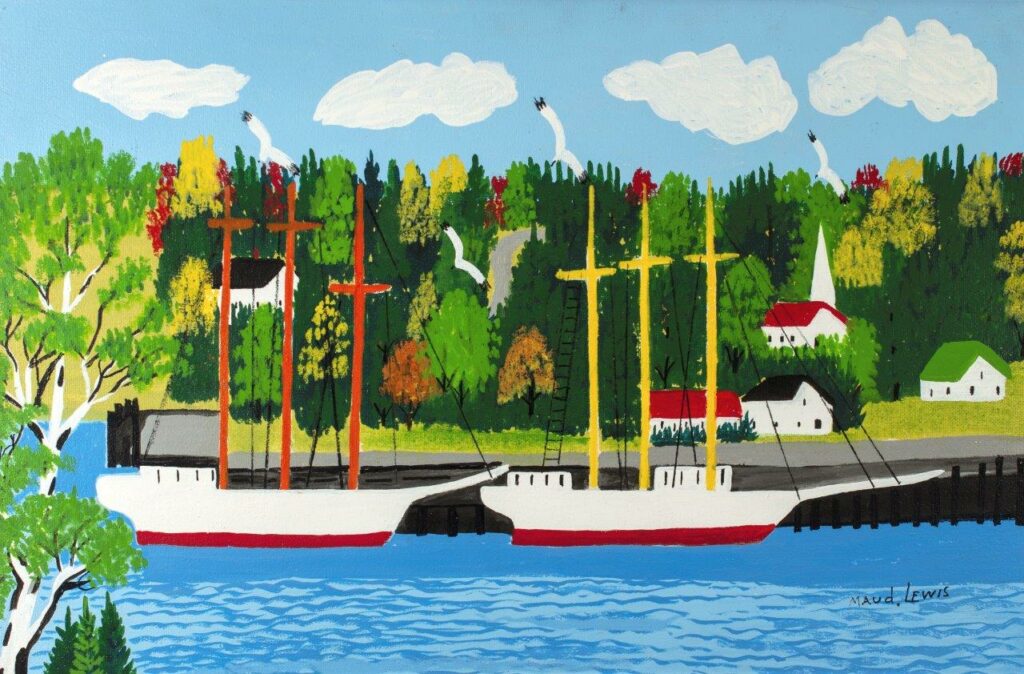

The major themes in Maud Lewis’s paintings all coalesce under one theme—a sentimental look back at the rural past of her part of Nova Scotia. In Lewis’s painted world, life can seem to be one long succession of sleigh and carriage rides, blossoming fruit trees, sailing on calm waters, and just enough honest work to keep active—woodcutting, fishing, farming. In her paintings fields are plowed by teams of yoked oxen; people travel by horse-drawn sleighs, carriages, and wagons; and wind powers the boats that go out on the sea. These subjects appear in works such as Haywagon, 1940s, Buggy Ride, 1940s, and The Bluenose, c.1960s, as well as in historic photographs from Nova Scotia in the early 1900s. Her nostalgia is understandable, as her own life had undergone profound changes from her childhood, when she grew up in a comfortable home with supportive parents, to her adulthood, living in poverty with her husband. That personal change was mirrored by the societal change underway across rural Nova Scotia.

-

Maud Lewis, Haywagon, 1940s

Oil on pulpboard, 23 x 30.5 cm

Private collection

-

Bill Spurr with his wagon, 1942

Photographer unknown

-

Maud Lewis, Buggy Ride, 1940s

Oil on board, 22.9 x 30.5 cm

Collection of CFFI Ventures Inc. as collected by John Risley

-

Family with horse and buggy, possibly W.H. Buckley’s family at their carriage, Guysborough, Nova Scotia, c.1910

Photograph by William H. Buckley

The tourists who bought so much of Lewis’s work were seeking a simpler life away from the hustle and bustle of cities. In the postwar period, as now, Nova Scotia was marketed as an escape, a return to a simpler time. The poignancy of Lewis’s physical challenges and the poverty in which she and Everett lived have been huge factors in the marketing of Maud Lewis, but it is also a fact—her days by any contemporary standard were poor, hard, and filled with pain and want. Who would blame her for being nostalgic?

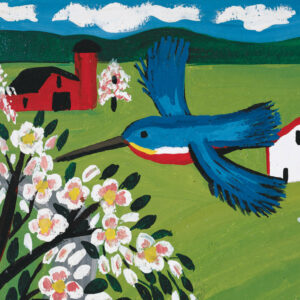

A certain innocent joyfulness permeates Lewis’s paintings. Her skies are always blue, birds abound, flowers are in bloom, and the people depicted, whether working or playing, always seem to be cheerful and contented. She unabashedly made happy paintings, brightening up even the winter scenes with sunshine and colourful clothing, sleighs, and buildings. Sometimes, if the mood struck, she even added colourful fall hues to winter scenes, as she did in The Sunday Sleigh Ride, n.d. When asked about that, she would simply say, “It was the first snow fall.” The world in Lewis’s paintings, while not entirely devoid of shadows, seemingly never saw rain, fog, or darkness. That was a deliberate decision on her part, of course, and as with the work of any artist, it reflected her vision of the world―or at least, the vision she wanted to communicate.

Depicting Nova Scotia

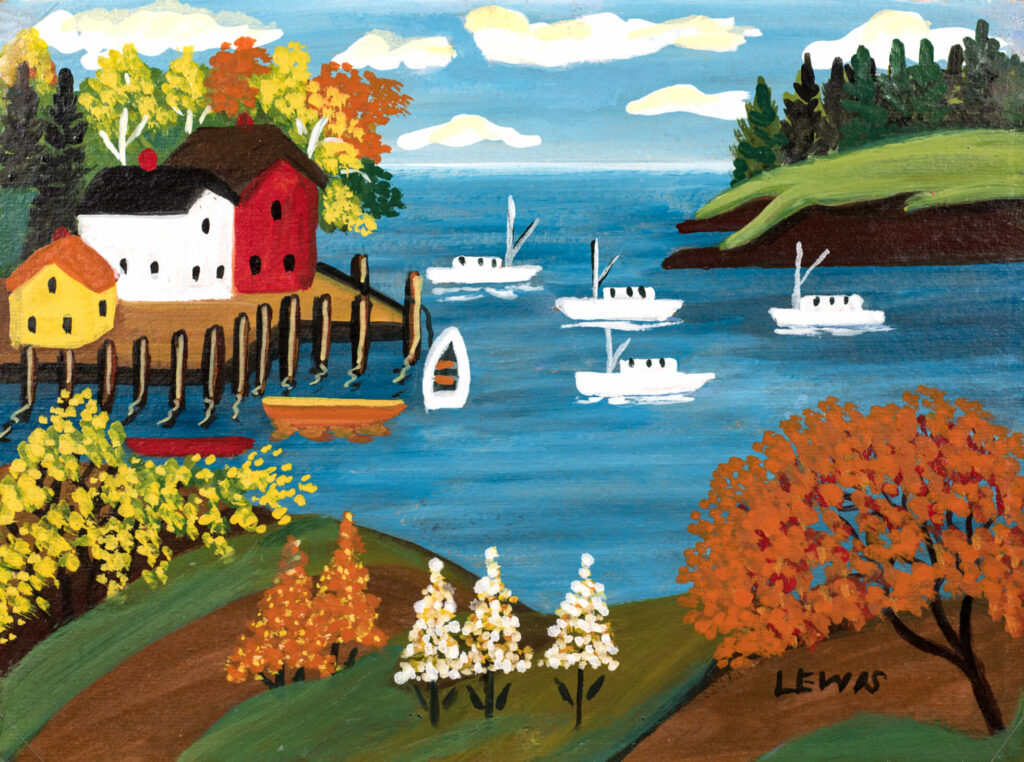

Maud Lewis over the course of her long career developed a very particular vision of Nova Scotia, one that was nostalgic and optimistic. It was just what her customers wanted. By the 1950s she had stopped copying other sources, and, in a distinctive style, consistently depicted her region. The harbours reflect the tidal waters of the Bay of Fundy, with mud flats at low tide, and the distinctive high wharves needed to deal with the extreme height differences between high and low tides. The countryside she paints is her own, with the trees, flowers, and animals one would expect to see in Digby County. No longer do we see hoop-skirted women waiting for a train, as in Train Coming into Station, c.1949/50. Rather, in paintings such as Oxen and Logging Wagon, c.1960s, we see farmers and loggers in the familiar red woollen coats of rural Nova Scotia, and oxen with their distinctive Nova Scotia yokes. She does not show parts of the province she did not know herself: there are no scenes of Halifax, Cape Breton, or the villages and churches of the South Shore. These may have been destinations for many of Lewis’s customers, but they were not part of her world. She painted the county she knew, as in The Docks Pier, Bear River, n.d.

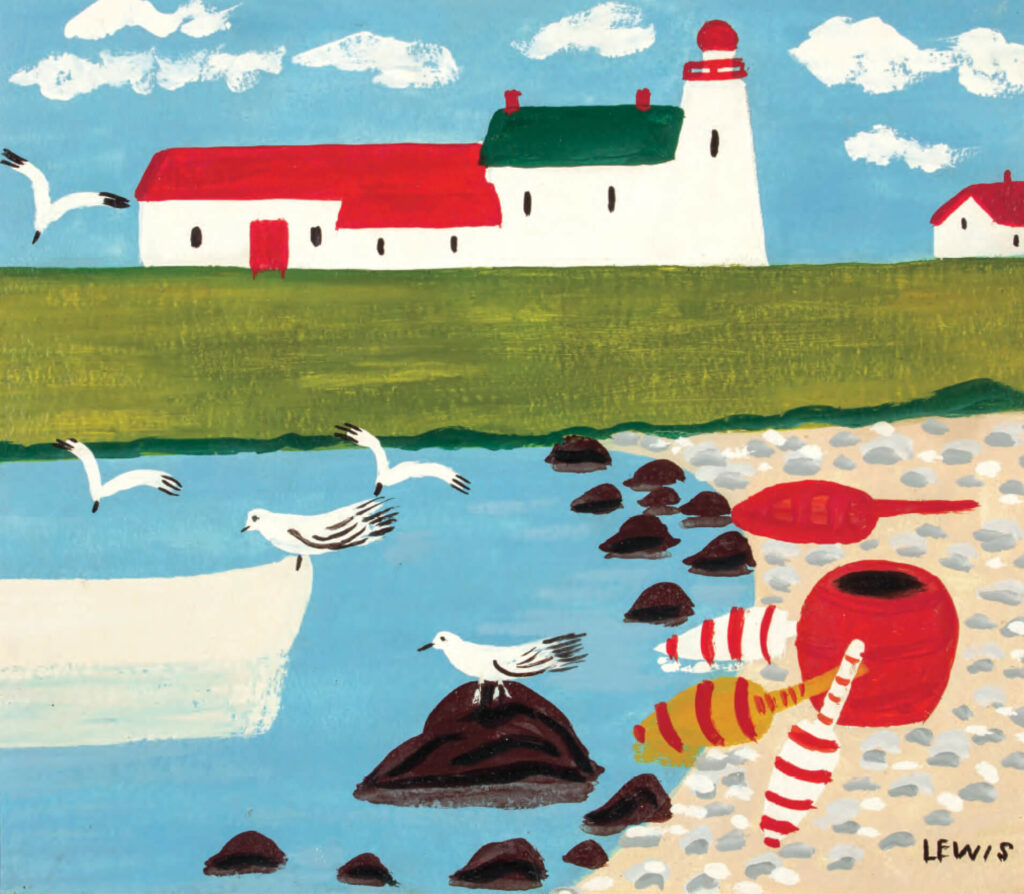

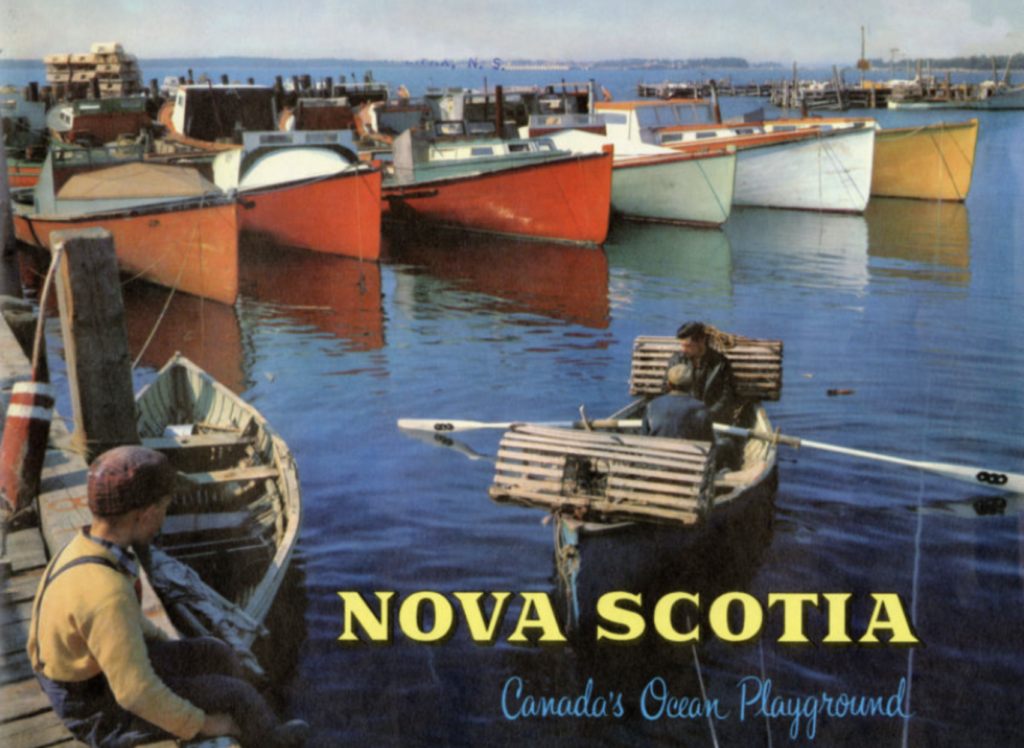

Her artistic vision of Nova Scotia eventually helped change the way Nova Scotians saw their own province, becoming, as the licence plates proclaim today, “Canada’s Ocean Playground,” a phrase also seen in tourism brochures. As art historian Erin Morton has noted, “If the activities represented in Lewis’s paintings, from travel in horse-drawn buggies to farm and fishing work, no longer organized everyday life in rural Nova Scotia in the 1960s and 1970s, they could at least help to visualize…a joyful representation of its past simplicity.” Lewis’s vision of that “past simplicity” has become a central feature in how Nova Scotia still presents itself to the world―coastal scenes, like that in her painting Lighthouse and Gulls, n.d., continue to be popular.

In 2019, six contemporary Nova Scotian artists were grouped with Lewis in a three-city exhibition in China. The exhibition’s title—Maud Lewis and the Nova Scotia Terroir—conveys the curator’s thesis that Maud Lewis and the other artists in the exhibition were expressing something about the character of the province through their work. As curator Sarah Fillmore wrote, “just as the terroir informs the taste of wine, the themes that came from this place inform and colour the works being produced here.”

Titles, Dates, and Attributions

Maud Lewis sold her pictures unframed, and in the early years they were often unsigned. When she did sign them, she did so in varying ways: just “Lewis,” “M. Lewis,” “Maud. Lewis,” and plain “Maud Lewis”. One way she never signed her work was as Maude—despite the persistent trend to spell her name with that final “e.”

-

These three paintings show how similar Lewis’s paintings of cats are.

Maud Lewis, Three Black Cats, 1955

Oil on pulpboard, 30.5 x 30.7 cm

Private collection

-

Maud Lewis, Three Black Cats, n.d.

Mixed media on beaver board, 30.5 x 35.6 cm

Private collection -

Maud Lewis, Three Black Cats, n.d.

Oil on board, 30.2 x 30.2 cm

Collection of CFFI Ventures Inc. as collected by John Risley

Lewis rarely titled any of her paintings, nor did she date them. Any titles they have were usually applied afterwards by the owners of the paintings, by art dealers and auctioneers, and by curators who were exhibiting her work. Most are simply descriptive: Three Black Cats, Digby Harbour, Oxen and Logging Wagon, and so on. Over the years, paintings have been shown under different names, and it is only with the increased entrance of her work into public collections that titles are becoming fixed.

The lack of such information on the works themselves, and Lewis’s practice of making multiple copies of the same or of similar images, complicates the study of her work. Images such as those of the mother cat and kittens, for instance, can date from any period from the mid-1950s to the late 1960s, and she made dozens of versions; the selection in the adjacent image gallery illustrates the motifs she repeated regularly, such as the tulips and floral branches. If records were kept by the original purchaser that can help, but Lewis never kept such records herself.

Where it is possible to determine the dating of her work, at least in broad strokes, is in her use of materials. In the 1950s and early 1960s her work was mostly made with materials that were either scrounged by Everett, or readily available in Digby’s hardware stores. That meant that her paints were often marine or house paints, for instance, even water-soluble poster paint. After the mid-1960s she began using artist’s oil paint, often sent to her by fans in other provinces, such as Ontario painter John Kinnear (1920–2003). What she painted on changed as well, with the increased demands (and revenue) prompting Everett to buy pre-cut Masonite panels rather than gathering boards or using cardboard for Lewis to paint on. Collectors, curators, and art conservators such as Laurie Hamilton are able to reliably date works from different periods by examining the materials Lewis used. This method is still inexact, of course, in that it ascertains a range of years, even decades, rather than months, and it accounts for the vague dating on so many of Lewis’s works.

Finding Fame and Rise of Folk Art

Maud Lewis, with her popular success in her lifetime, was the forerunner of an explosion in what became known as “Nova Scotia Folk Art.” Folk art, or art made by untrained artists, is by no means confined to Nova Scotia, and traditionally it has meant decorative objects made by people for their own use. Folk art, for many decades, was usually found in history museums. Indeed, many art galleries, including the National Gallery of Canada, continue to exclude folk art from their collecting mandates. But beginning in the 1970s there developed in the province a burgeoning movement that was unique in that it shared with fine art the trappings of galleries, collectors, and touring exhibitions. Fuelled in no small part by the recognition won by Lewis as an artist, folk art from Nova Scotia began to be taken seriously as a fine art and found a new home in art galleries such as the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

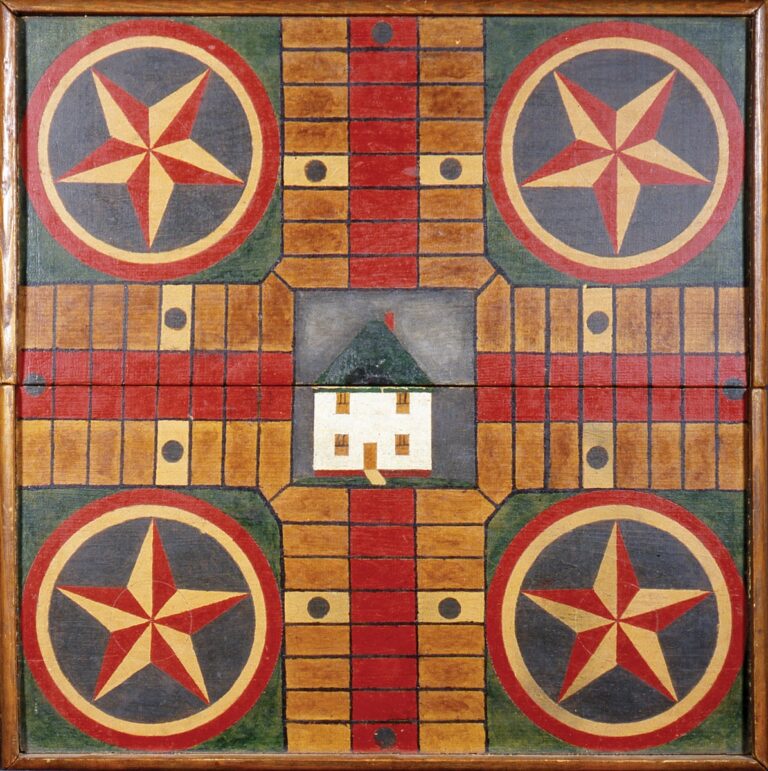

There has been folk art in Nova Scotia since the arrival of colonists. Many of the few settler artists in Nova Scotia’s early art history were non-professionals, as likely to paint houses or signs as they were portraits or landscapes, following the demands of the market. In a society where consumer goods were rare and expensive, many people simply made their own luxuries, items such as game boards, like the Mason Family Parcheesi Gameboard, c.1925, decorative ironwork, like the Trotting Horse Weathervane, c.1920s, and even children’s toys and wallpaper. Early folk art in Nova Scotia, as in the rest of colonial Canada, was part of the day-to-day lives of its creators.

Lewis was among the first Canadian folk artists to emulate the art market of larger centres. Her paintings were produced not for herself, but for sale, making her distinctly different from the rug hookers who made floor coverings for their cold houses, or carvers who decorated the yokes that their oxen wore when plowing their fields. In Nova Scotia, before Lewis, collectors found folk art in the homes and barns of rural villages, and it was the act of collecting that turned a tool, a blanket, a weather vane, or some other utilitarian object into “art.”

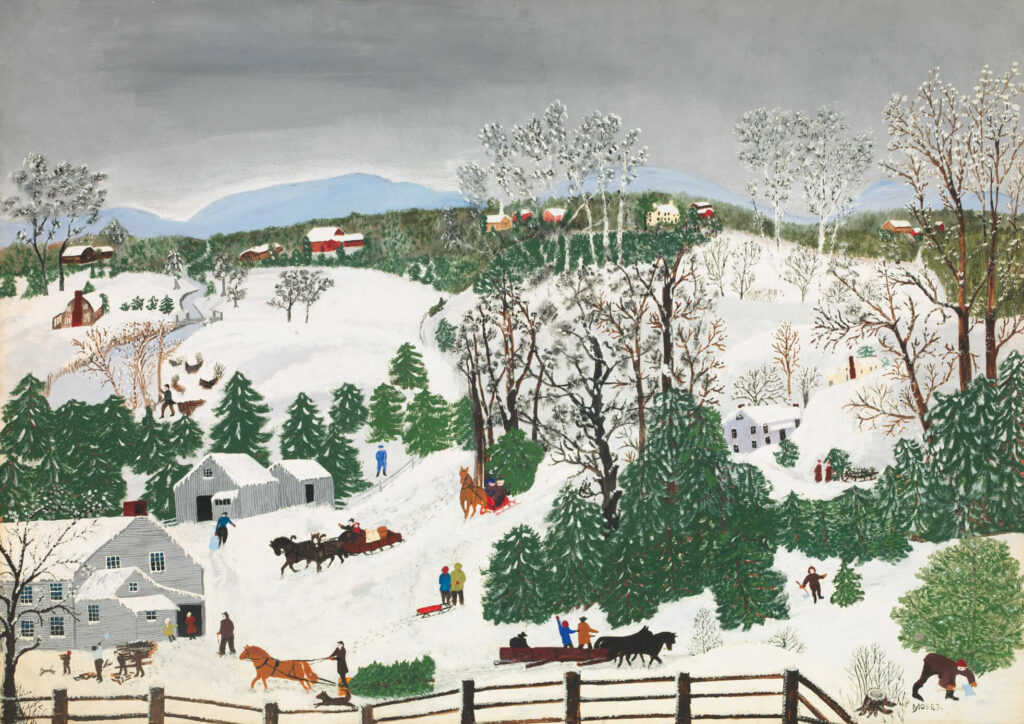

Lewis has often been compared to the American folk artist Anna Mary Robertson Moses (1860–1961), known as Grandma Moses. In fact, that comparison was made in the first article written about Lewis, in Toronto’s Star Weekly in 1965. Both artists depicted nostalgic versions of their home regions and were influenced by popular prints by such makers as Currier and Ives. In another parallel, Lewis suffered all her life from debilitating arthritis, and it was Moses’s inability to continue with her hobby of embroidery due to her own worsening arthritis that turned her to painting. Moses achieved much more fame in her lifetime, despite starting her painting career in her late seventies.

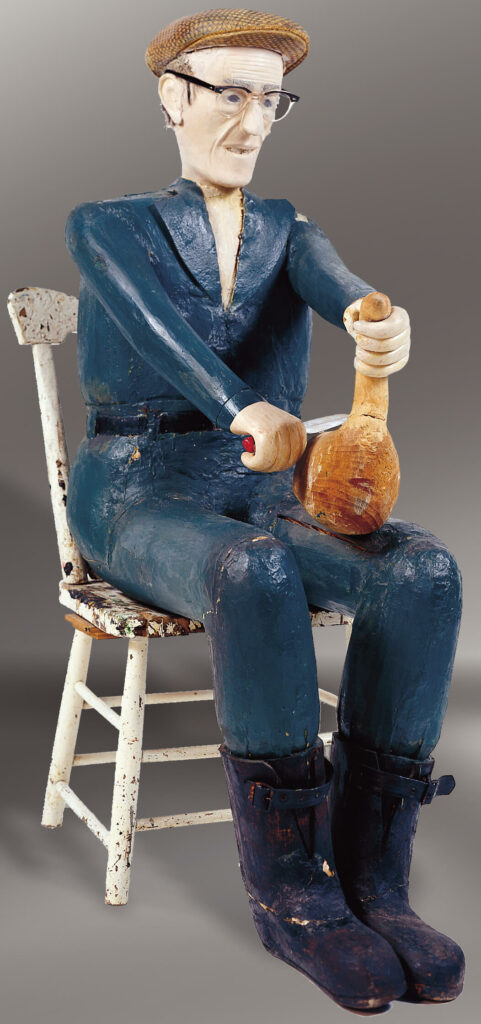

Though in interviews she resisted the designation of artist, Lewis was making objects that were obviously art: painted landscapes offered for sale. She changed the folk art dynamic by making objects whose only function was to please the eye―and unlike many of the Nova Scotia folk artists who followed her, she was never “discovered” by a collector or curator. She took her work to the market herself. Lewis, and later Nova Scotia folk artists such as Joe Norris (1924–1996), Collins Eisenhauer (1898–1979), and Ralph Boutilier (1906–1989), made work that was intended to be displayed, and the emerging style of Nova Scotia Folk Art was as gallery-dependent as any of the modernist art movements of the twentieth century.

With the surge in popularity of folk art, tied to the promotion of the tourism industry, Nova Scotia’s most enduring artistic exports have become the products of the vernacular cultures of its regions, not the art produced in its major centre, Halifax. That city may be the economic engine of the province and the home of most of its artists, but it was the folk art produced in Lunenburg and Digby Counties that caught the general public’s attention, not the Conceptual art coming out of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design from such stalwarts as Gerald Ferguson (1937–2009) and Garry Neill Kennedy (b.1935).

Despite her popularity, it took a while for Lewis’s impact on Canadian folk art to be recognized by scholars and curators. One of the first books to document Canadian vernacular art, J. Russell Harper’s A People’s Art: Primitive, Naïve, Provincial, and Folk Painting in Canada (1974), did not mention Lewis. It is common to find exhibitions and publications from the 1950s through the 1980s that also neglect the artist who has now become not only Canada’s most famous folk artist, but also one of the country’s best-known artists of any description.

Lewis died in 1970, and her work was never exhibited in public art galleries or museums in her lifetime. The Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, the institution most linked with Maud Lewis, was not even incorporated until 1975, despite having roots that stretch back to 1908. The first touring exhibition organized by the fledgling gallery was called Folk Art of Nova Scotia. It opened in 1976 and toured to several Canadian galleries, including the National Gallery of Canada. Four of Lewis’s paintings were included in that exhibition (as were three of Everett Lewis’s). She was not the star of that exhibition, however; that accolade went to woodcarver Collins Eisenhauer, a folk sculptor from Lunenburg County. Lewis was treated almost as a footnote to the show, whose catalogue and publicity materials highlighted the personalities of the (mostly) living artists who were included.

For many years there was little institutional interest in Lewis’s work, except from the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. The Canadian Museum of History, then known as the National Museum of Man, actively collected Nova Scotia Folk Art in the 1970s. It has only a few paintings by Lewis in its collection. The National Gallery of Canada has none. In 1983 a nationally touring folk art exhibition was organized by the National Museum of Man, and while it included works by several Nova Scotia folk artists, Lewis was not among them. It was not until 1997 that she was the subject of a touring museum exhibition. However, in 2019 her work was the subject of a major solo exhibition at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Ontario, the gallery often thought of as a monument to the Group of Seven, and the location of the final resting place of six of the group’s members. With the increasing interest and fame of Lewis’s work, there has been a meteoric rise in the price of her paintings.

The House That Maud Built: Maud Lewis and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia

The story of Maud Lewis’s posthumous fame is intimately connected to the history of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, which owes much of its existence to the efforts to preserve and celebrate Lewis’s legacy. From the first public exhibitions of her work through the marketing and promotion of her life and work as a brand, the gallery’s cultural and economic position has been intimately tied to the story of Maud Lewis. That story has most often been told by the gallery’s curators, most notably the founding curator and first director, Bernard (Bernie) Riordon, who curated the first touring show of Lewis’s work in 1997.

The Art Gallery of Nova Scotia has been described as the house that Maud built. As with many such sayings, there is as much truth as untruth to it, and while there is undoubtedly much more going on at a public art museum of the scale of this institution, it is also true that Nova Scotia Folk Art, and Lewis in particular, have helped define the gallery over its history. The most important kernel of truth to the expression “the house that Maud built” is the role that Lewis and her painted house played in securing a permanent home for the gallery.

The Art Gallery of Nova Scotia began as the Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts, a collecting society founded in Halifax in 1908. Lacking any building of its own, the museum mounted periodic exhibitions and collected works when it had the funds. In 1968 the Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts opened the Centennial Gallery in a powder magazine in Halifax Citadel Hill National Historic Site. This exhibition space showed both the collection and temporary shows mounted by the Centennial Gallery’s small staff, including its curator, Riordon. The museum operated this art gallery for ten years, until 1978, when the magazine was restored to its historical state.

In 1975 the Nova Scotia Museum of Fine Arts became the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia and moved into the former home of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. This space, however, was never large enough to serve the gallery’s needs, and as it was owned by Dalhousie University it was always going to be a temporary home. Plans were put in motion for a permanent solution. Then, in 1984, the province―acting with the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia’s full support and advice―acquired Lewis’s painted house, and this served as a major spur of the proposal for a new home for the gallery on the Halifax waterfront.

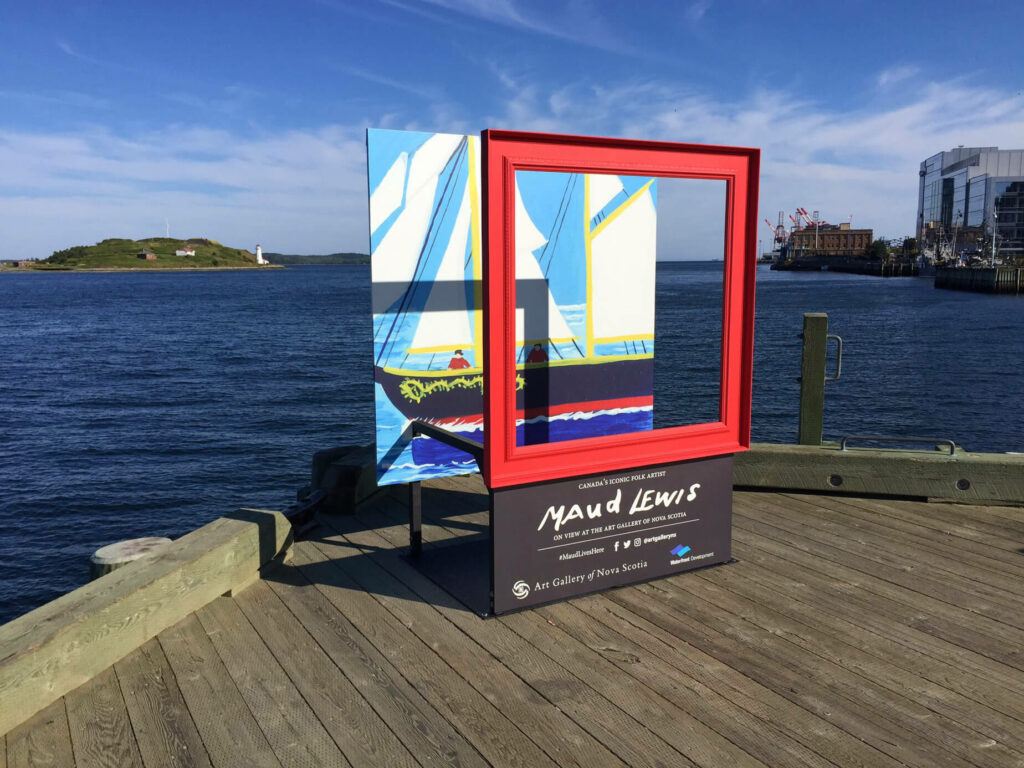

While there were many factors that combined to create a permanent place for the gallery after over seventy-five years of rootlessness, Lewis and her house played a decisive part. Ironically, the plan for a building on the waterfront holding the painted house was killed by the same political factors that had brought the project to the brink of success. The land went to a private developer, and an abandoned historic building across the street from the provincial legislature was given to the art gallery. The new Art Gallery of Nova Scotia opened to the public in 1988, but with no space for Lewis’s house. It was not until 1997, with the opening of an expansion of the gallery, that it went on display in the Scotiabank Maud Lewis Gallery, along with a permanent exhibition of her work.

Lewis’s significance as an artist is an ongoing creation. Her most iconic work, the house, exists only because of a long-term and extensive restoration effort. That hundreds of thousands of dollars and countless hours were spent saving the house of an artist who never received more than a few dollars for her work has struck many as ironic. But Lewis’s fame grew so much after her death that the Nova Scotia public was unwilling to let her house disappear. From its earliest media exposure in the 1960s, the painted house was a major focus. That the house had remained in storage from 1984 only added to the pressure to preserve it. As one headline read just before the conservation efforts started in earnest, “Crumbling Home Is Where the Art Is.”

From the 1980s, successive provincial and federal governments had continued to fund restoration studies, and public and corporate support for finding a way to display the restored house to the public continued to grow. By 1996, with plans in place for an expanded Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, it was time to start restoring the house to its condition when the Lewises lived there. A grant from the Department of Canadian Heritage’s Museums Assistance Program supplemented funds raised by the gallery and provided by the province. This permitted the gallery to hire a team of conservators and restorers, led by Senior Conservator Laurie Hamilton, to start in on the painstaking task of restoring the full beauty of the house.

From the outset, the push to preserve this distinctly Nova Scotian national treasure had been a collective effort, from local volunteers through to provincial and national institutions and corporations. With the work finally ready to be undertaken, that collective spirit was again in play. Space in Bedford’s Sunnyside Mall was donated so that the conservation team would have room to work. The location also meant that much of the initial work could go on under the public eye.

The conservation process for the house was extremely complex and proceeded in stages from stabilizing the actual structure through to restoring the painted surfaces and finding or replacing the furnishings and other items that had been in it during Maud’s and Everett’s lifetimes. For example, the gallery had been able to acquire the wooden storm door that had originally been one of its familiar painted elements. Apparently, a Digby area restaurant owner had approached Everett about displaying it as a form of advertising. The door ended up for sale in a Halifax art gallery and was purchased by the province for the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. The intention was to reinstall it on the house, but the conservators found that the door had been cut down—trimmed at the top and bottom. Luckily, none of the painted elements had been affected, and the conservation team was able to add aged pine boards to the door, treated to blend with the original. With the dimensions restored, the team reattached the door to the house.

This mixture of detective work, science, and all-around problem solving was repeated over and over again as the house and its contents were worked on by the gallery’s team of conservators. The restored Painted House opened to the public in June 1998. It quickly became, and remains, one of the most popular exhibitions in the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, and one of the main reasons people seek out the gallery from across the world. Since the house has been on display, the gallery has made a comment book available to visitors. Over the decades thousands have shared their reactions to the house and the account of Lewis’s life. Her art and story continue to resonate.

Our Maud: A Canadian Icon

Maud Lewis’s work, as well as her increasing posthumous fame, helped spark a new movement in Canadian art—Nova Scotia Folk Art—that continues to grow to this day, with its own galleries and avid collectors. Nova Scotia Folk Art has become a style in its own right, with an annual exhibition in Lunenburg, the Nova Scotia Folk Art Festival, that has been running since 1989. Lewis’s enduring popularity has been reflected in an acclaimed feature film, Maudie (2016), a novel by award-winning Nova Scotian author Carol Bruneau (Brighten the Corner Where You Are, 2020), and a special series of holiday postage stamps issued by Canada Post in 2020.

Lewis and her painted house remain one of the pillars of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia’s exhibitions and programs, and perhaps nowhere more so than in its educational activities. Since 1997 Lewis’s art, house, and story have played a central role in programs teaching Nova Scotia children about creativity and overcoming adversity. Laura Kenny’s AGNS’s Employee of the Month, 2018, is a creative tongue-in-cheek reflection on Lewis’s significance to the museum, which has even set up selfie stations featuring her paintings; several are installed along the Halifax waterfront.

The contrast between Lewis’s hopeful and happy paintings and the grinding poverty of her own life and the constant pain that she must have been in from her arthritis and other conditions is the defining element in any story of her life and art. Because Lewis left so little record of her own thoughts and opinions, there are as many versions of her story as there are tellers. The opinion of Lance Woolaver, whose biography Maud Lewis: The Heart on the Door (2016) is the most thorough treatment of her life, has evolved from seeing Lewis’s work as an expression of her overcoming her circumstances and an example of stubborn optimism despite them, to also perceiving her as a victim of Everett’s manipulation. Art historian Erin Morton sees her as being used as a prop to fulfill a naive, tourism-centric view of Nova Scotia in her book For Folk’s Sake: Art and Economy in Twentieth-Century Nova Scotia (2016). In contrast, Bruneau’s fictional Lewis is fiercely independent and self-aware.

In Lewis’s lifetime there were suspicions that she was exploited by her husband, who kept all the money she earned. After her death, the way that her story was used to promote the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia and the province of Nova Scotia sparked other criticism. But simply seeing Lewis as a victim of exploitation is perhaps simplistic. After all, she painted for a market, not for herself (though her house, its interior at least, is an exception to that rule), and she had been doing so since she was a teenager. Painting had long been Lewis’s way to contribute to the household income, whether she was living with her parents, with her aunt, or with her husband. Everett benefited from the proceeds of Lewis’s paintings. But then, so did she benefit from Everett’s work, and from his cooking and keeping house. Hero or victim, whatever interpretation we put on Maud Lewis and her work, it is bound to be subjective.

Just as there are actual shadows in Lewis’s work, there were undoubtedly shadows in her life. That she was poor is irrefutable. She suffered terrible pain. But was she also happy? Based on her work, and on the memories of those who knew her, it is hard to argue the contrary. After all, Lewis was born in a time when people expected life to be hard, and she was always dependent on others for her food, shelter, and any comforts in life. Perhaps she had fewer expectations than most? In marrying Everett, however, she found a certain security. She took control of her life, finding the only kind of autonomy that most people in rural Nova Scotia at that time could imagine for a poor woman with no family (or societal) safety net.

Maud Lewis may have been a victim, but she was also a hero, and in overcoming adversity she transcended the starkness of her day-to-day life. In the end, it is to her paintings that we must look to examine her outlook—these, and her painted house, are the evidence she has left. Lewis’s work continues to enchant, decades after her death, and her hopeful example of finding joy even in the shadows is her enduring legacy.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements