Maud Lewis (1901–1970) has become one of Canada’s most renowned artists, the subject of numerous monographs, novels, plays, documentaries, and even a feature film. She was born into relative comfort and obscurity, and died in poverty, though enjoying national fame. She overcame severe physical challenges to create a unique artistic style, and sparked a boom in folk art in her home province. Though she rarely left her tiny house, her works have travelled around the world, and in the decades since her death she has become an iconic figure, a symbol of Nova Scotia, and a beloved character in the popular imagination.

Early Life

Maud Lewis’s life was bounded by the distance between two of southwestern Nova Scotia’s major towns—Digby and Yarmouth. She was born in the hospital in Yarmouth on March 7, 1901, raised in the neighbouring small village of South Ohio, and lived most of her adult life closer to Digby, in the village of Marshalltown. The distance between the two towns is just over a hundred kilometres, stretching along the Bay of Fundy shore of one of Nova Scotia’s remoter coasts.

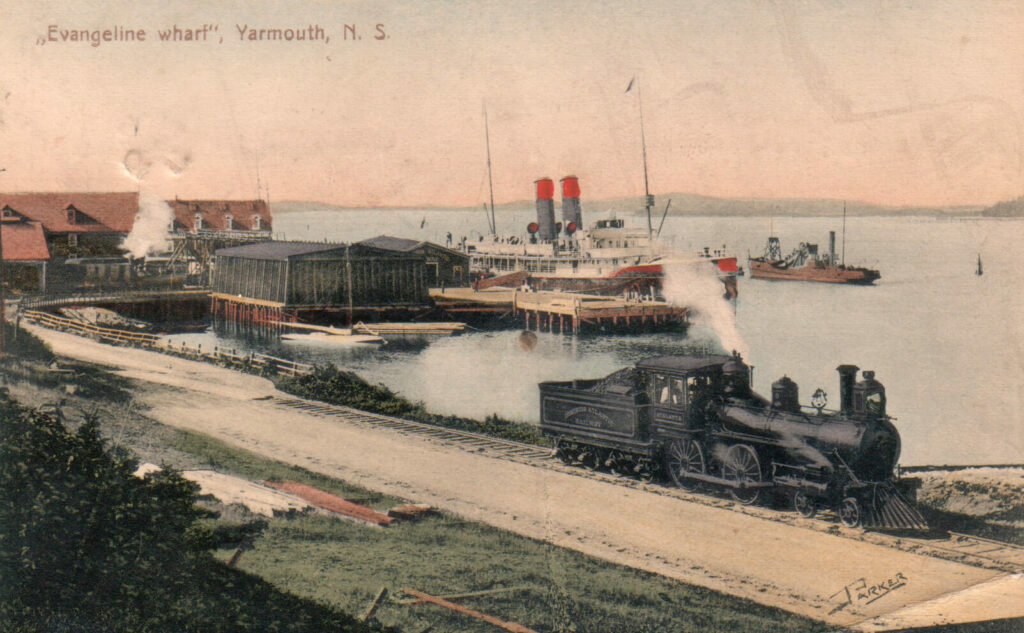

Today, Digby to Yarmouth is a short drive of about an hour, along a reasonably modern highway. In Lewis’s childhood, of course, it was a different story, with few motorized vehicles and a dirt road that followed the shore, linking a chain of small fishing villages that dotted the coast. Most travel between the two towns, in that early part of the twentieth century, would have been undertaken by train or boat, then much more efficient modes of long-distance transportation. In 1965, for a CBC Television program, Lewis explained that the furthest she had been from her home was Nova Scotia’s capital. “Halifax, that’s the furthest I’ve been,” she said. “And that’s a long time ago, before I got married.”

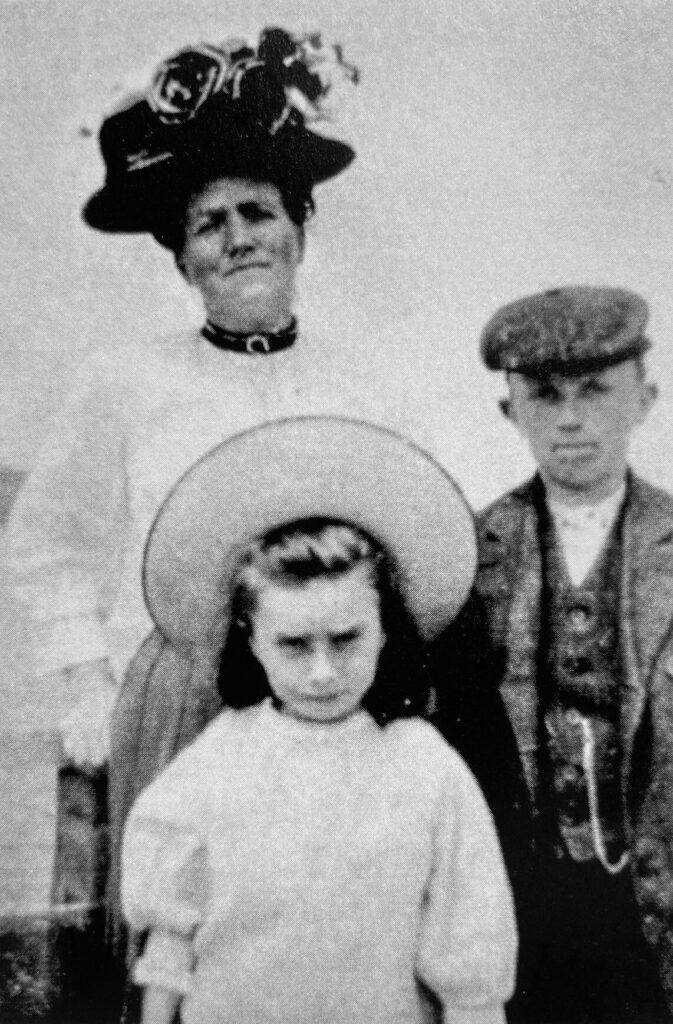

Maud Lewis was born Maud Kathleen Dowley, and she was the only daughter of John Nelson Dowley and Agnes Mary German (also spelled Germain and Germaine). She had one older brother, Charles, who was born in 1897. Her mother subsequently gave birth to two more children, neither of whom survived more than a few days.

Lewis was born with congenital disorders that included acutely sloping shoulders, a curvature of her spine, and a severely recessed chin. She was small and frail, and there was little that her doctors could do for what remained an undiagnosed condition in her lifetime, short of treating the constant pain she must have endured. Over the years there have been attempts to diagnose her conditions, including suggestions that she suffered from polio or arthritis. The consensus now, based on photographs of her and on descriptions of how her condition worsened over the years, is that she was born with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. This condition is degenerative and can be extremely painful. It was little understood at the time.

Because of her physical challenges, Lewis was not an extremely active child, but nor was she a shut-in. She grew up, rather, in the sheltered milieu one might expect would surround the youngest child, and only daughter, of a family in small town Nova Scotia in those years. Lewis’s mother encouraged her daughter’s interest in the arts. She learned to play the piano and to draw and paint. These, along with sewing and decorative arts such as embroidery and crocheting, were considered suitable hobbies for young middle-class girls, and Lewis was no exception. She attended a one-room schoolhouse in South Ohio.

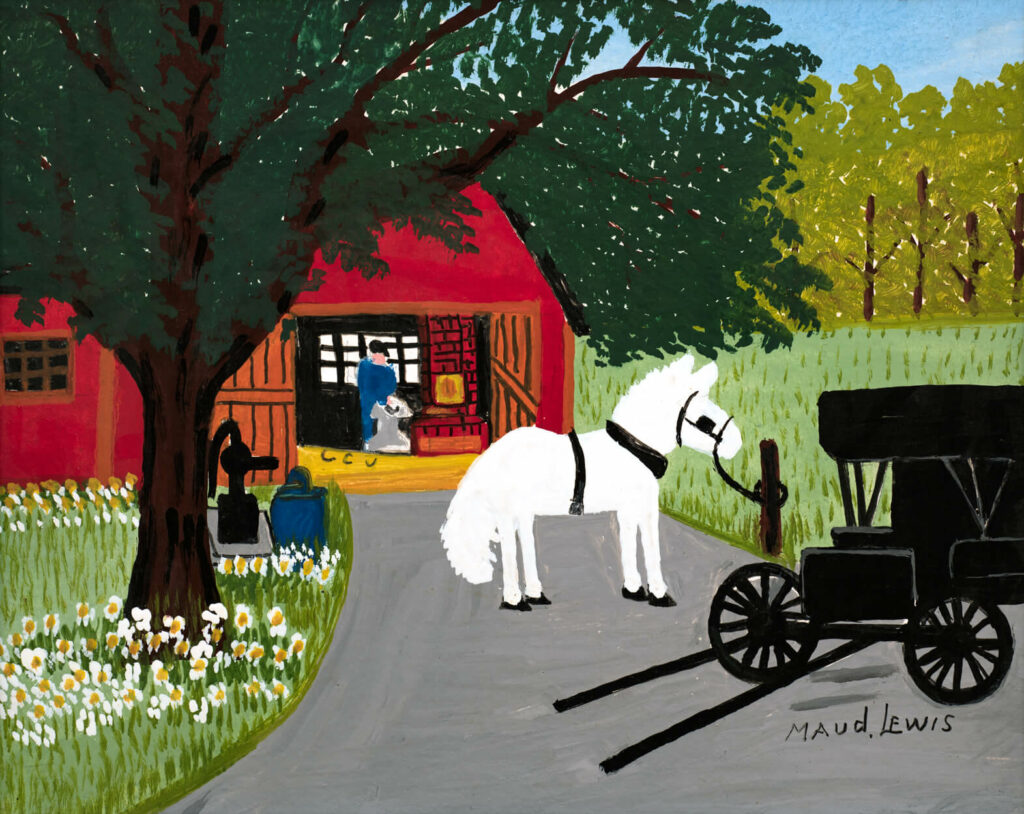

She was not raised in luxury by any means, but her childhood did not feature the cyclical, and always pressing, poverty of many of the surrounding farm and fishing families. Her father was a skilled craftsman—a blacksmith and harness maker, a subject that Lewis would later depict in paintings such as Blacksmith’s Shop, 1960s. These trades carried significant weight in the community and enabled John Dowley to provide a comfortable living for his family.

Lewis was born into a time of profound change for Nova Scotia and the world. The Victorian age was passing, and technology was encroaching on the rural lifestyle of Yarmouth and Digby Counties. The great shipyards of the age of sail that had once fuelled prosperity in towns and villages all along Nova Scotia’s coast had been dying for decades, and even farming was changing, with horses and oxen giving way more and more to steam and then the internal combustion engine in the form of tractors and other heavy machinery. Automobiles were becoming more popular, and many people were being drawn off the land and the uncertain life of farming and lumbering, and into the cities and factories. It was, of course, the same story everywhere in the Western world, but the fact that the change was shared made it no less significant to Lewis and her family.

Years in Yarmouth

Maud Lewis was thirteen in 1914 when her family moved to Yarmouth from South Ohio and rented a house on Hawthorne Street. Her father set up a harness shop on Jenkins Street and from there developed a reasonably prosperous business that continued for over thirty years. Her brother, Charles, had already moved to Yarmouth, and he worked there as the manager of the Capitol Theatre. He was also a musician, a saxophone player in a dance band called the Gateway Four. Yarmouth was a bustling town in the 1910s and 1920s, with an active port for fishing, shipping, and passenger service to New York and Boston.

Lewis completed the fifth grade at the age of fourteen. This was behind the norm, when a child of that age would have been expected to have reached Grade 6 or 7, but it is not known if she was held back by her health or by other considerations. Her biographer, Lance Woolaver, has suggested that her disabilities, which became more severe as she grew up, led to her leaving school early. In his view, “It seems likely that illness and her physical deformities played a role in this decision [to leave school]. Children made fun of her in the streets and mocked her flat chin.” Of course, in a time and place where many people received little formal education (Lewis’s future husband, Everett Lewis, only completed the first grade), her progress, or lack thereof, may also indicate that school itself was not consistently offered.

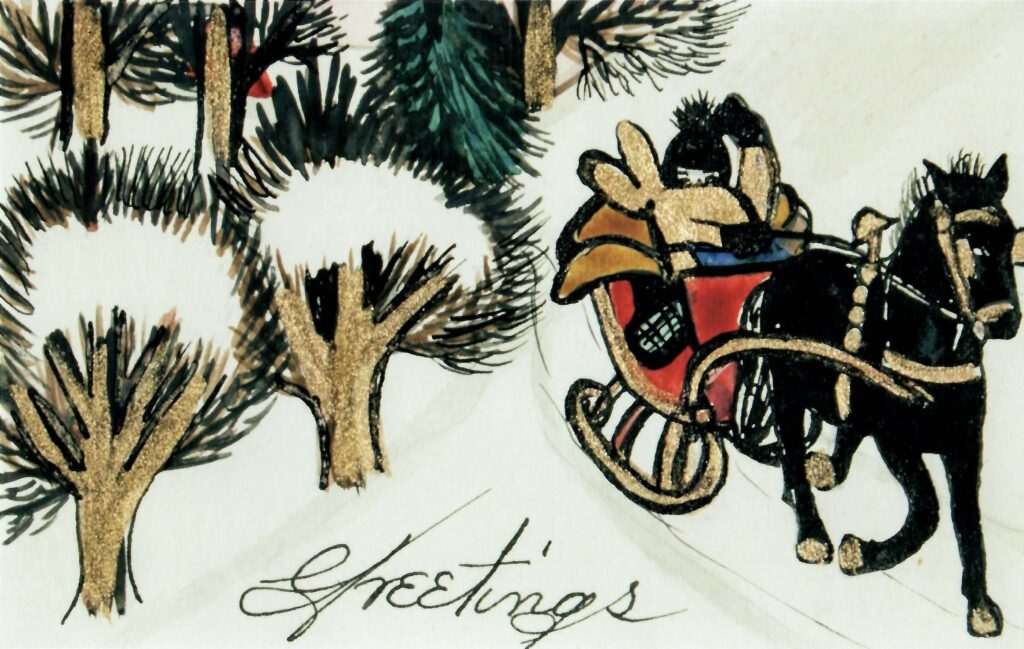

Not much is known of Lewis’s life in Yarmouth, though a few photographs of her as a young woman do survive. She never had a job, and she lived at home with her parents. With her mother, however, she did turn her hand to a few commercial enterprises, including making Christmas cards and decorations and selling them door to door. In the early 1920s, a friend and local business woman, beauty salon owner Mae Rozee, began selling Lewis’s cards and painted trays in her shop. While long remembered in Yarmouth, little of what she made from this period has been found to date. It is likely that the work she was selling in the early 1930s was drawn from popular imagery such as Christmas cards or other commercial illustrations.

While not much is known about Lewis’s personal life before her marriage, one important fact was that she gave birth to a child, Catherine Dowley (later Muise), in 1928. Lewis never acknowledged Catherine as her child. Woolaver, whose research into this aspect of Lewis’s life is detailed in his monumental book Maud Lewis: The Heart on the Door (2016), was able to contact Muise’s descendants. In an interview with journalist Elissa Barnard in 2017, Woolaver recounts that Lewis rebuffed Catherine Dowley: “The child went to Marshalltown to reunite. Maud said, ‘My child was a boy born dead. I’m not your mother,’ and at the time there were three grandchildren. Maud never accepted her child. She attempted to contact Maud again in a letter.” In the same interview with Barnard, Woolaver identifies the father, a man named Emery Allen, who abandoned Lewis when she became pregnant.

In 1935 Lewis’s father died. Her mother did not survive him long, dying in 1937. Lewis was left with nothing—what little estate there was went entirely to her brother, Charles. She briefly lived with Charles and his wife, Gert, but later in 1937 their marriage broke up, and Charles let the lease go on the family home on Hawthorne Street. Her maternal aunt, Ida German, offered her support, and Lewis moved to Digby to live with her. She spent the rest of her life in this county, and painted it many times, as can be seen in White House and Digby Gut, 1960s.

“Live-in or Keep House”

Maud Lewis may have moved to Digby, but she did not live with her aunt Ida for long. In the autumn of 1937, Everett Lewis, a forty-four-year-old fish peddler, put up advertisements in some of the local stores. He was looking for a woman to “live-in or keep house” for his small house in Marshalltown, just outside of Digby.

Everett was born in 1893 and raised in the Alms House, known locally as the “Poor Farm.” In those days before social welfare programs, the Alms House was an institution where people without means were sent by the authorities. Residents were expected to work on the farm or at outside jobs to subsidize their forced accommodations. Everett’s father had abandoned his family and they were sent to the Alms House as indigent. His mother was eventually released from the Poor Farm to become the housekeeper to a local farmer. Everett worked as a labourer throughout his childhood, receiving little schooling, only completing the first grade. He never did learn to read or write.

Before Everett married Maud Dowley, he made his living selling fish from door to door in Digby County. He had an old Model T Ford that allowed him to bring fish bought from boats at the wharf to farms and homes further inland. He also did occasional work on farms and in lumber camps. In the 1920s he purchased a small plot of land adjacent to the Poor Farm from Reuben Aptt, the man for whom his mother was housekeeper. In 1926 he bought a small house and moved it by ox team to this land. Although the tiny white building would not have needed much keeping, he did not receive any responses to his ad. Except for one.

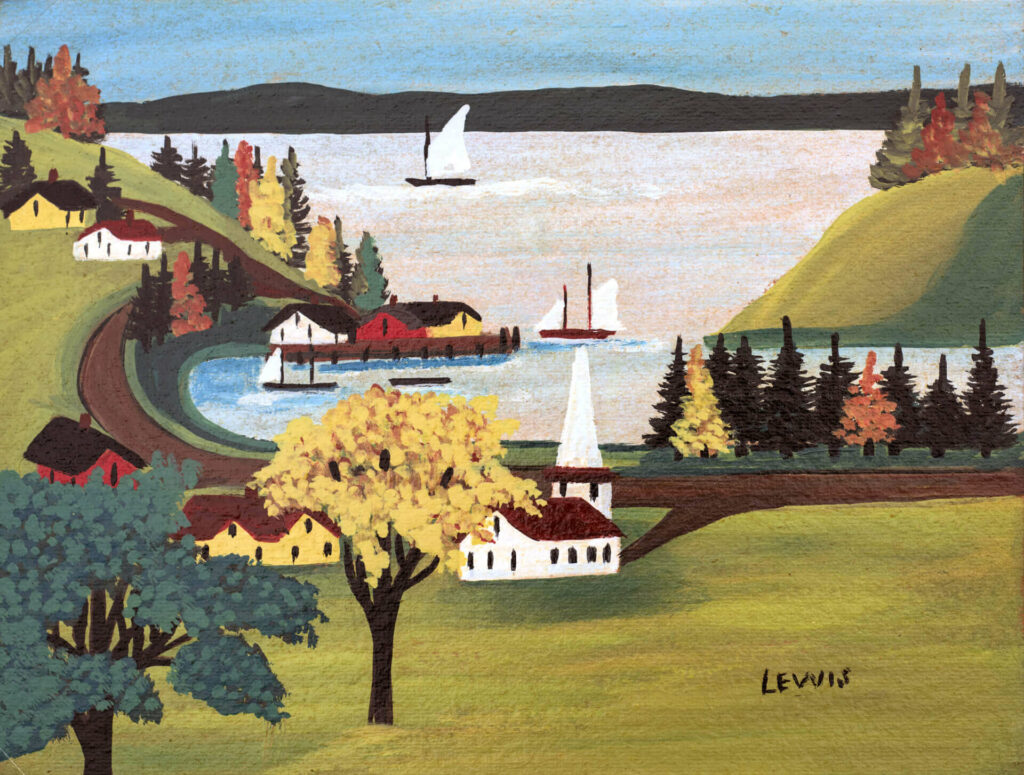

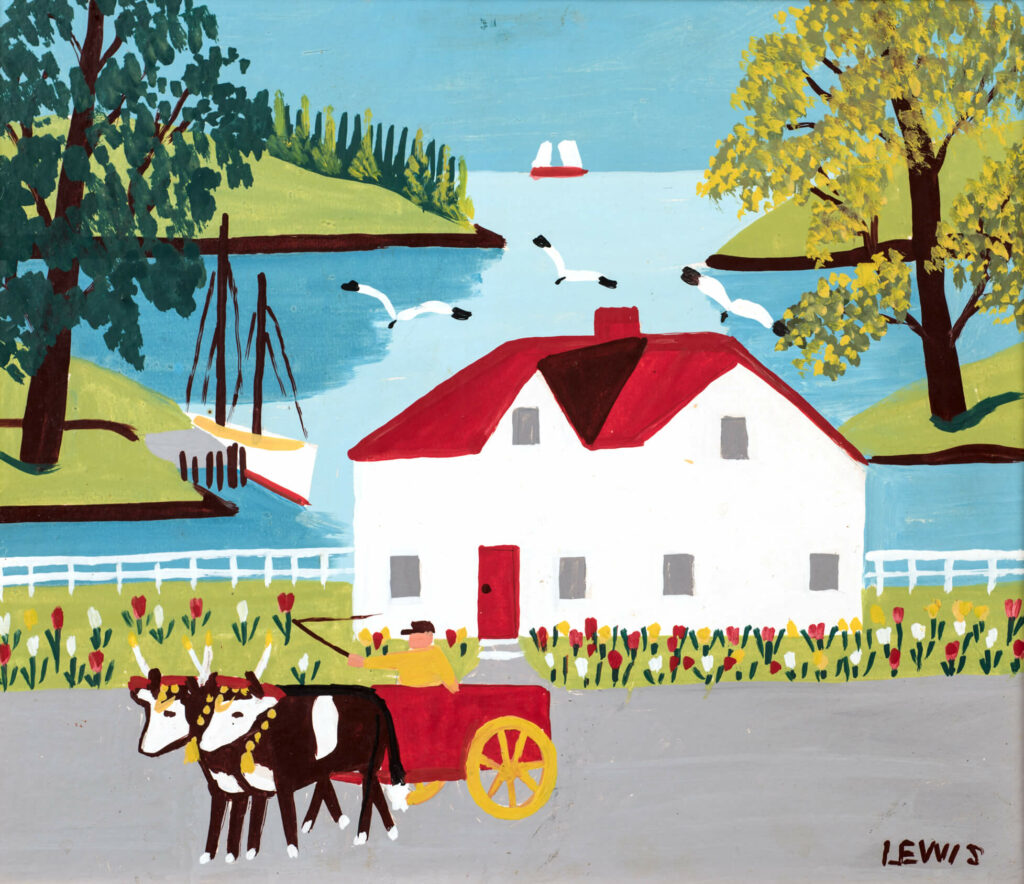

One morning in late 1937 Everett found Maud Dowley standing on his doorstep. She had walked from her Aunt Ida’s house in Digby, through the small village of Conway and along the railroad tracks to Marshalltown, a distance of about six miles. The two apparently did not immediately hit it off, and Everett walked her back to the railroad underpass, about a mile down the road, and then left her to walk back to Digby on her own. A few days later she returned to the house, and they struck a bargain: she would move in with Everett, but on one condition—she was not to be a housekeeper, but his wife. She lived there for the rest of her life, and the local area became one of the main subjects of her art, as can be seen in Smith’s Cove, Digby County, c.1952.

The couple married on January 16, 1938, and Maud Lewis moved into the one-room house by the side of the highway. It is small by any definition: thirteen and half feet of frontage, twelve and half feet wide at its side, and just fourteen feet, four inches high at its peak. The house is a single storey, though its attic was used as a sleeping loft. The ground floor walls are just under six feet from floor to ceiling. Many visitors to the house over the years reported that Everett had to tilt his head to avoid hitting the ceiling when he stood.

The house had two windows on the ground floor, and there was a small window in the sleeping loft. It had little insulation and was heated by a large cast-iron cook stove. The concrete foundation had a shallow space at the back of the house (the site sloped downward from the highway) that the couple used for cold storage. There was no electricity or running water. The toilet facilities were an outhouse in the yard, and bathing was done with a wash basin or small tub filled from the well, with water heated on the stove.

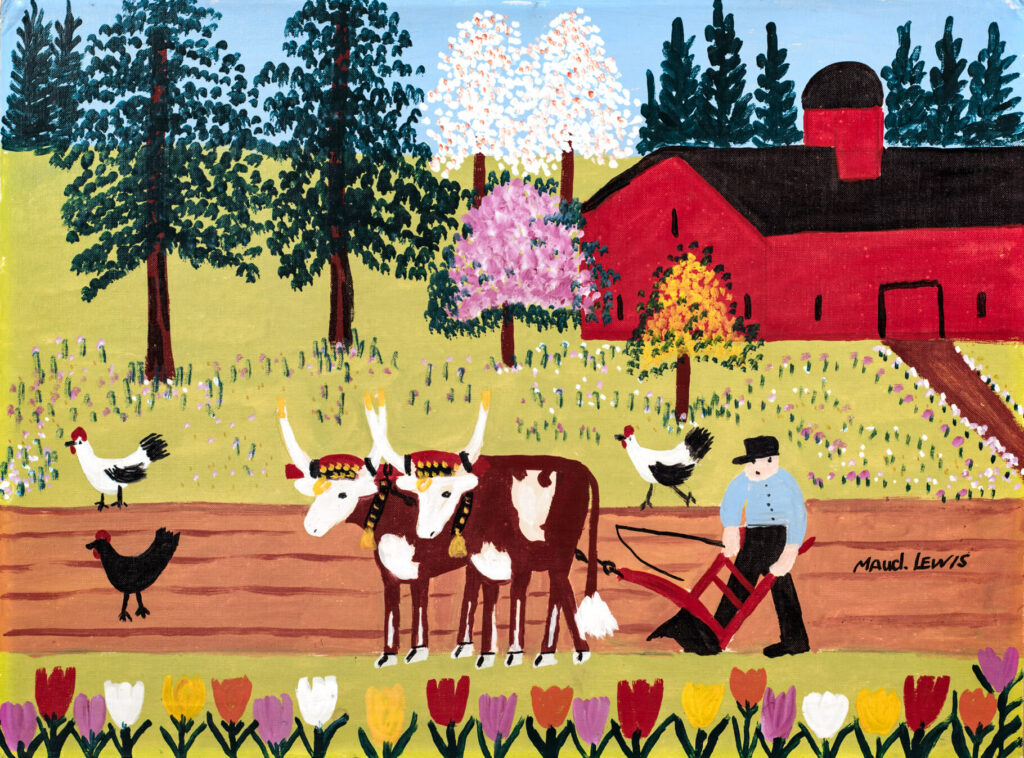

On their wedding day Lewis was thirty-six years old (although she claimed to be thirty-four), and she had little to bring to the marriage—no land or other possessions, and no money from her family. She was physically unable to do the sort of job outside the home that would have been normal for working-class women of her time in rural Nova Scotia: working in a fish plant, or cooking in a lumber camp, for instance. As the daughter of a skilled tradesman, Lewis had not been raised in the working class, where even the children would be expected to find employment of some sort in the plants, camps, and fields. Now, with the deaths of her parents and the estrangement from her brother, she had been left to the charity of her aunt. Her marriage to Everett introduced her to a world of poverty that she had not previously known. It was a community of rural labour, work that Lewis would later represent in paintings such as Everett Plowing, 1960s.

While Everett had advertised for someone to keep house, that is not how the relationship between the two worked out. Lewis was soon unable to handle even routine chores. Her arthritis, a progressive and degenerative disease, caused her hands to gnarl up into tightly closed fists, and her back and neck conditions made it very difficult for her to climb stairs or lift anything heavy. Eventually, Everett did all the household work while Lewis found another way to contribute: she began to paint again, first the cards that she had used to sell in Yarmouth, and then the paintings that would secure her fame. She also began to paint her home, which is now known as Maud Lewis’s Painted House and on display in the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

Paintings for Sale

Since her teen years Maud Lewis had been making and selling cards both door to door and in shops. After marrying Everett in 1938, she began painting again in earnest, making cards for sale. In the warm months of May to October the couple would tour the back roads in Everett’s car, selling fish and brightly painted cards. Lewis, always shy, would stay in the car while Everett did the bargaining.

In 1939 Everett took a job as a night watchman at the neighbouring Poor Farm, which meant that he no longer had his regular route and customers. Instead, Lewis painted a colourful sign to go on their house and began selling work directly from there. She also started making paintings, which sold for more than the cards and whose sales were not limited mainly to holidays. Through the 1940s she worked on both cards and paintings, as well as commissions, such as a series of shutters she made for an American family with a summer home in the area. Eventually she stopped making cards for sale altogether.

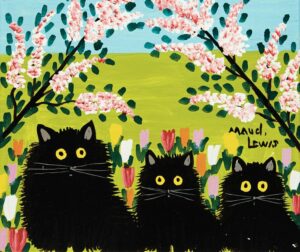

By the 1950s Lewis had developed what would become her major subjects: the family group of cats, her long-lashed oxen, sleigh and carriage rides, and her couple in a Model T, among others. Everett soon took on the role of Lewis’s main salesman and her assistant in getting paint and boards for her paintings. For many years he cut the boards to size, though by the end of her life she was buying Masonite pre-cut to set dimensions.

Lewis’s increasing popularity came at a cost. Her arthritis caused her constant pain, which was only exacerbated by the cramped conditions under which she worked, hunched over a small table as she produced painting after painting. That her work remained so bright and cheerful despite her health and difficult living situation is one of the most remarkable aspects of Lewis’s life story.

The location of Maud and Everett’s house, by the side of the main road connecting Yarmouth and Digby, along the route to Annapolis Royal, Grand Pré, and, eventually, Halifax, made it a natural location for a roadside business. The summer tourist season, with Americans and travellers from the rest of Canada arriving by the Yarmouth and Digby ferries, supported many small businesses in rural Nova Scotia, fuelled by a postwar boom in tourism that affected all of North America.

The increased prosperity after the Second World War, more reliable automobiles, and investments in better roads all served to bring customers to the little house in Marshalltown. Passersby could stop and see examples of Lewis’s work, and if they bought a work, they would also leave with a sweet pea boutonniere from Everett’s garden. Early on she also painted on scallop shells, which were widely available on the Digby beaches. These shells, painted with cats, flowers, and butterflies, were used as dishes and ashtrays. In time, she stopped making them in favour of her paintings.

Maud and Everett did little to promote her work; their roadside business was entirely dependent upon people driving by and deciding to stop. Sales happened only in Nova Scotia’s brief summer period, and Lewis painted throughout the winter months to ensure enough stock for the coming season. Over the decade of the 1950s her reputation continued to grow with local people and visitors alike. Stopping at Mrs. Lewis’s to buy a painting or two became part of many people’s summer rituals. As a story in the Halifax Chronicle noted on her death in 1970, “visitors soon crowded her tiny cottage, all anxious for her to produce for them examples of her art.” One such visitor was Sally Tufts, who visited with her parents while they were vacationing in the Digby area. “I was fascinated by how small the House was,” she told Lance Woolaver, “and amazed that every inch was painted in bright colours.”

In the early 1960s, Claire Stenning and Bill Ferguson, who ran an antique shop and art gallery in Bedford called Ten Mile House, began to show Lewis’s work. They were among her first supporters, and they made many efforts to get her work noticed outside of Digby County. In their gallery they sold framed paintings by Maud Lewis—for $10, twice what an unframed piece would cost if bought directly from the artist. They also had silkscreen prints made of Lewis’s work, in efforts to find new markets, but the low price point of her paintings made all these efforts go in vain. Anything they tried to do to make the paintings more widely available ran against the rocks of Maud and Everett’s insistence at keeping the prices low. As Stenning told an interviewer in 1965, “They’re afraid to charge very much for the paintings because they’re afraid that they will lose their market.”

In the Spotlight

Maud Lewis’s painting career would likely have remained a mostly local phenomenon but for Halifax freelance journalist Cora Greenaway, another early promoter of Lewis. Greenaway produced an interview with Lewis for the CBC Radio program Trans-Canada Matinee that aired in February 1964. The interview sparked public interest and in July 1965 the Star Weekly (Toronto) sent freelance writer Murray Barnard from Halifax to write about Lewis. He was accompanied by photojournalist Bob Brooks, whose images of Lewis and her painted house have become iconic. The Star Weekly, which was included in the Saturday edition of Canada’s largest circulation newspaper, the Toronto Star, created an enormous amount of curiosity about, as its headline read, “The Little Old Lady Who Paints Pretty Pictures.” “Among the brightest and most joyful pictures coming out of picturesque Nova Scotia at present,” wrote Barnard, “are those done by a little old lady named Maude Lewis who admirers call Canada’s Grandma Moses [Anna Mary Robertson Moses (1860–1961)].”

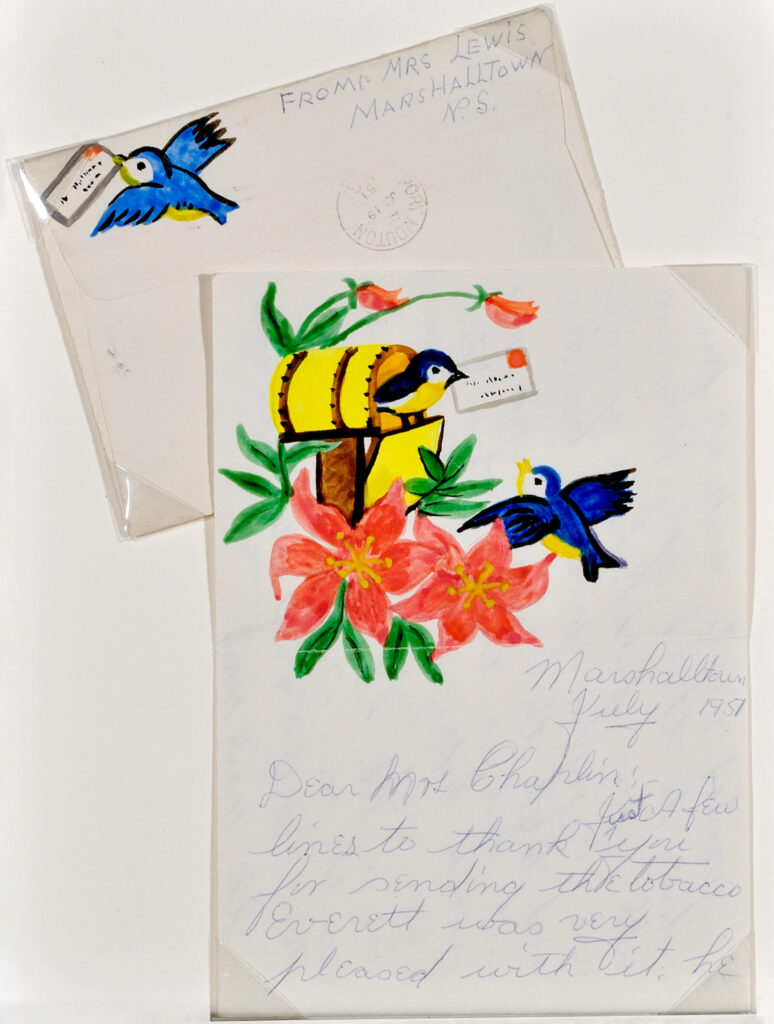

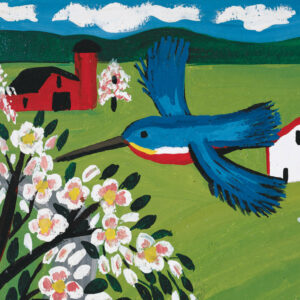

Many people wrote to Lewis requesting paintings after the article ran, creating a rush on her work that never abated for the rest of her lifetime. (In those days, a letter addressed to “Mrs. Maud [or Maude] Lewis, Marshalltown, Nova Scotia” was sure to find its way to the tiny house beside the highway.) Lewis did not allow her growing fame to change her subject matter, continuing to depict her nostalgic images of the local past, such as the horse-drawn sleigh, as well as the animals and plants she saw in her day-to-day life, such as the cheerful goldfinches amidst the apple blossoms of Yellow Birds, c.1960s.

That same year, Maud and Everett were visited by a camera crew from the CBC television program Telescope. The crew interviewed the couple, as well as their neighbour, Kathleen MacNeil, who acted as Lewis’s secretary and adviser, answering the many letters she received and mailing paintings to people who sent cheques and cash in the mail. In the interview, Mrs. MacNeil recounted how Lewis was uncomfortable taking money from people for paintings that she hadn’t completed as yet, feeling that she should only get paid for work that existed. The orders just kept coming, however, spurred in no small part by the media attention.

The Telescope program is one of very few instances we have of Maud Lewis speaking about her painting and where she found her signature style. “I put the same things in, I never change,” she said. “Same colours and same designs.” She went on to talk about where her imagery came from: “I imagine I’m painting from memory, I don’t copy much. I just have to guess my work up, ’cause I don’t go nowhere, you know. I can’t copy any scenes or nothing. I have to make my own designs up.”

Also interviewed on the program were Claire Stenning and Bill Ferguson, from Ten Mile House, who had been trying to increase the market for Lewis’s work as well as attempting to raise the prices. She refused. By the mid-1960s the paintings were still five dollars, and Lewis could hardly keep up with the demand. For Lewis, fame meant little but increased work. Despite the added household income brought by the increasing demand for her paintings, no improvements were made to the couple’s day-to-day lives: the house never had running water or electricity, and Everett never bought a car.

In addition to Stenning and Ferguson, painter John Cook (1918–1984) was interviewed, and he was among the first to describe Lewis’s work as art, calling it “a direct statement of things experienced or imagined.” Characterizing her use of colour and drawing as “forthright,” he concluded emphatically that her paintings were “definitely works of art.” This was a change from Murray Barnard, for example, who described Lewis as a “primitive” artist, “concerned with everyday experience” as opposed to “the prevailing art forms.” Whether Lewis’s art needed a qualifier such as “primitive” has been long debated, but little doubt now remains about her status as an artist in her own right. Asked by the CBC interviewer what she wanted most out of life, Lewis was characteristically modest: “Well, I’d like to have a little more room, to put my paints and stuff. I’d like to have a trailer. I imagine it costs too much for a trailer. I couldn’t afford that.”

Final Years

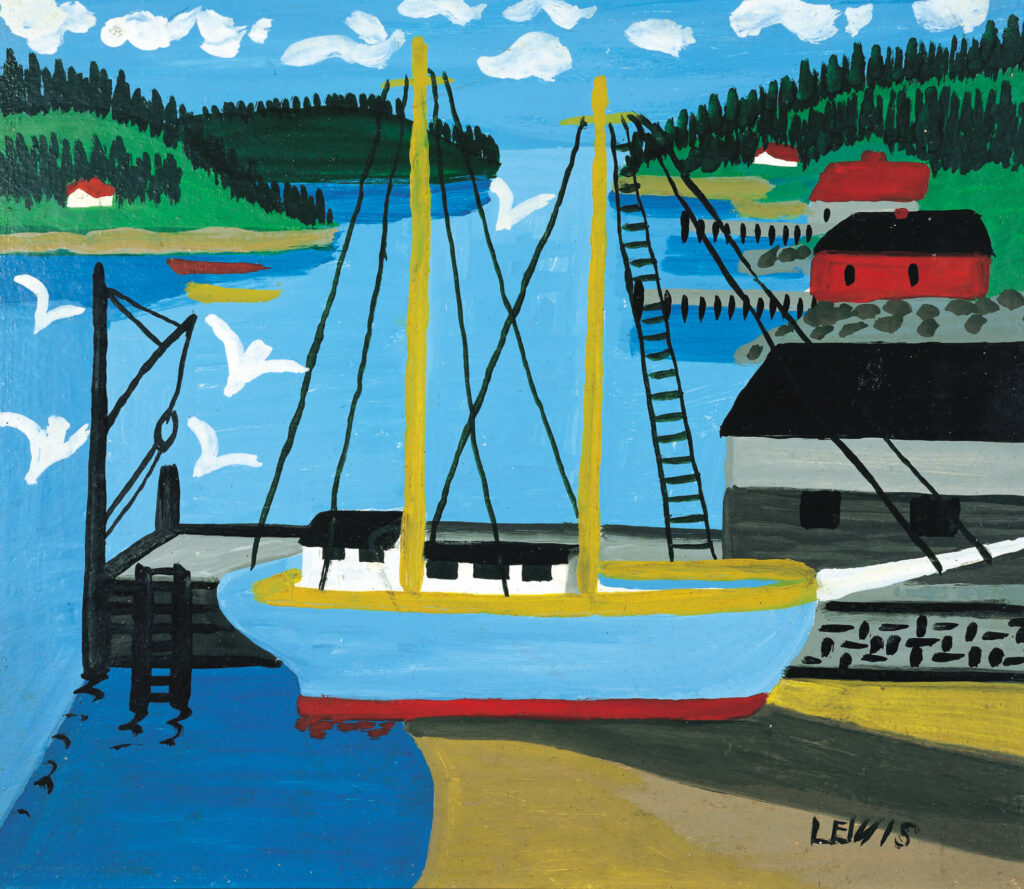

In her last years Maud Lewis had an increasingly difficult time keeping up with the demand for her works, and Everett helped by preparing her Masonite panels and doing some of the underpainting. Everett eventually began helping her with the actual images, painting some of the backgrounds and filling in the colours of some of the central figures. Nonetheless, her production fell off. She began using cardboard stencils made by Everett of her major themes, the oxen, cats, and covered bridges, to aid her. Everett also started making his own paintings, influenced by Lewis’s work, and often using the same stencils that he had made for her. In works such as Sailboat, 1975, we see Everett experimenting with a subject Maud had depicted many times, as can be seen in her painting Untitled (Ship at Dock), 1960s.

For the last few years of her life she worked in a used trailer set up beside the house, an arrangement to have extra space. However, her arthritis caused her more and more pain, and painting became increasingly difficult. In 1968 she fell and broke her hip, after which her health went into rapid decline. Still, when she went into hospital she made cards for her nurses. In 1970 Lewis died in the hospital and was buried in Everett’s family plot in Marshalltown. Her name is listed under that of his parents and his own, as Maud Dowley.

Everett Lewis controlled the money in their house, and by the end of Maud’s life he had a reputation as a miser—stories circulated that he had money buried in the backyard, or under the floorboards. After her death he spent even less and let the property decay. When Everett was eighty-six years old a young man broke into the house looking for the rumoured treasure. Everett surprised him, and in the ensuing struggle was killed. He left over $22,000 in a Digby bank account, as well as Mason jars full of cash hidden around the property. Lance Woolaver estimates that Everett may have had as much as $40,000 on his death.

After Everett’s death, the house and land were inherited by one of his relatives, who sold it to the Maud Lewis Painted House Society in 1980. While the house was later acquired by the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, the society decided that some sort of memorial was needed for the site. In 1997, they received a proposal for a memorial structure designed by Brian MacKay-Lyons, who offered to donate his services. The design, a steel structure with bright spots of colour from a red chimney that is illuminated from the inside, was meant to highlight the sombre poverty of Lewis’s existence, which she overcame through her art.

Maud Lewis died as one of Nova Scotia’s best-known artists, with her obituaries describing her as an “internationally known primitive style artist,” and how “in art circles, critics were high in their praise of her primitive style and the colourfulness of her paintings.” The Halifax Chronicle’s sub-heading to their story stated plainly, “She Gained International Fame.” Over the subsequent decades her fame has only increased. Paintings that she sold for five dollars now reach tens of thousands of dollars at auction, and her works hang in prominent art galleries across Canada. She is renowned for her smile and for her perseverance in the face of poverty, disability, and chronic pain. Her life was not always happy, and indeed, had many shadows in it. But despite all of that, her paintings remain as a testament to her optimism and courage in the face of adversity. As she told Telescope in 1965, “I’m contented here. I ain’t much for travel anyway. Contented. Right here in this chair. As long as I’ve got a brush in front of me, I’m all right.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements