Throughout her career, Mary Hiester Reid (1854–1921) distinguished herself as a highly trained, accomplished, and intellectual artist. Initially she began her studies in American art schools, but her extensive travels and studies in Europe exposed her to other art movements and techniques that also influenced her painting style. She explored various stylistic strategies in her art practice, drawing on the principles of high realism, the Aesthetic movement, French Impressionism, and Tonalist art. Her work earned her both critical and commercial success, but it is her floral still lifes that mark her as an artist of renown.

An Artist of Her Time

Though she was primarily regarded by art critics, journalists, collectors, and the public as Canada’s pre-eminent flower painter during her lifetime, Hiester Reid proved to be skilled at keeping pace with artistic principles and practices of her day. The key components in her agility at infusing these artistic strategies and trends into her work were her extensive studies and travels in North America and Europe.

She began her studies in earnest at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, taking classes with the award-winning portraitist Thomas Pollock Anshutz (1851–1912) and realist painter Thomas Eakins (1844–1916). Early canvases, such as Daisies, 1888, and Chrysanthemums, 1891, emphasize her initial academic training in North America, and specifically illustrate her attention to high realism. This element of her work is indicative of the influence of her studies from 1883 to 1885 with Eakins at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

After her marriage to fellow artist George Agnew Reid (1860–1947) in Philadelphia in May 1885, the couple spent their four-month honeymoon visiting London, Paris, Italy, and Spain. Upon their return to North America that fall, the couple set up a studio in Toronto and produced paintings and taught art classes. In 1888 they auctioned off enough work to afford a second trip to Britain and France. While in Paris, Hiester Reid enrolled in art classes at the Académie Colarossi, taking “costume-study and life classes” under Joseph Blanc (1846–1904), Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret (1852–1929), Gustave Courtois (1853–1923), and Jean-André Rixens (1846–1925). She returned to study at the Académie in 1896, when she and her husband toured Gibraltar and Spain.

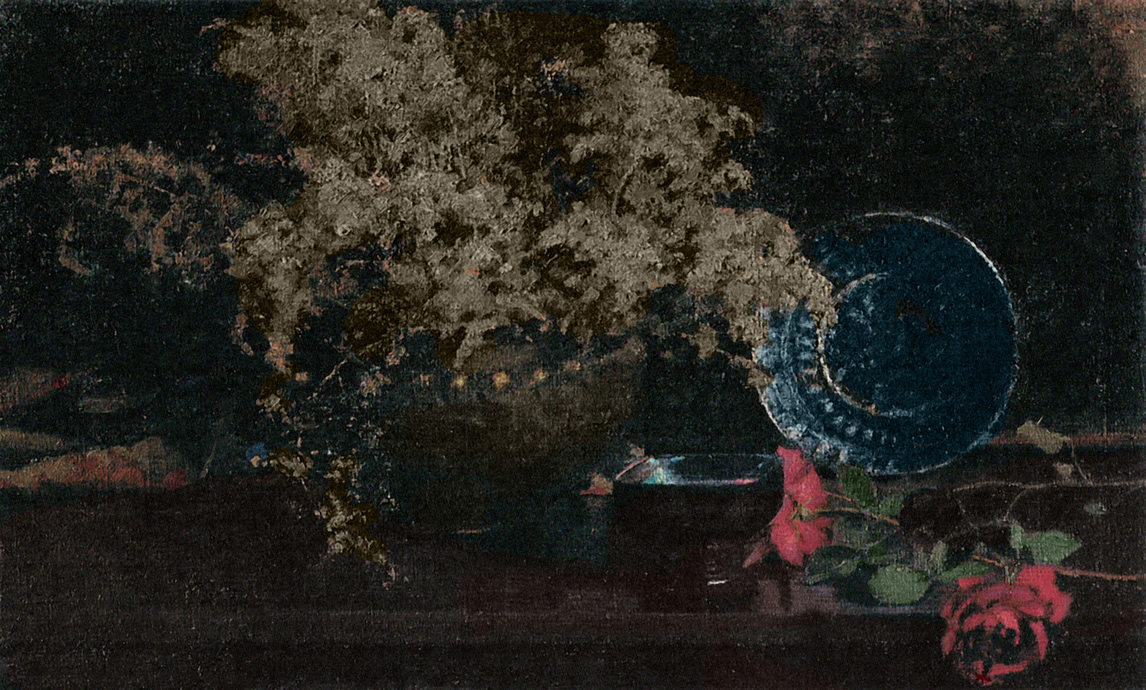

Paintings such as Chrysanthemums in a Qing Blue and White Vase, 1892, show Hiester Reid’s initial exposure to the ideas of the Aesthetic movement she encountered during her European travels. Inspired by art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900), proponents of the Aesthetic movement such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) championed the concept “art for art’s sake,” calling for the pursuit of beauty and self-expression in all facets of life, from interior design to fashion and painting. Hiester Reid’s dedication to the pursuit of beauty is later captured most assiduously in A Fireside, 1912, a painting of an interior replete with artfully arranged objects, flowers, and framed prints.

A Harmony in Grey and Yellow, 1897, and A Study in Greys, c.1913, call viewers’ attention to her skill in the manipulation and blending of colour as well as referencing the Tonalist paintings of Whistler. Tonalist art became popular in the United States around 1880, and was taken up by artists around the world. This painting style is characterized by artists’ use of a limited palette of soft, primarily dark, colours to showcase harmonious pictorial unity in their works. Whistler emphasized the visual harmony of Tonalist painting using musical terms in his artworks’ titles to call attention to the connection between an artist’s use of colour and a musician’s use of notes. Other well-known Tonalist practitioners were British painter Gwen John (1876–1939) who studied under Whistler from 1898 to 1899 at the Académie Carmen in Paris, France, and Australian artist Clarice Beckett (1887–1935).

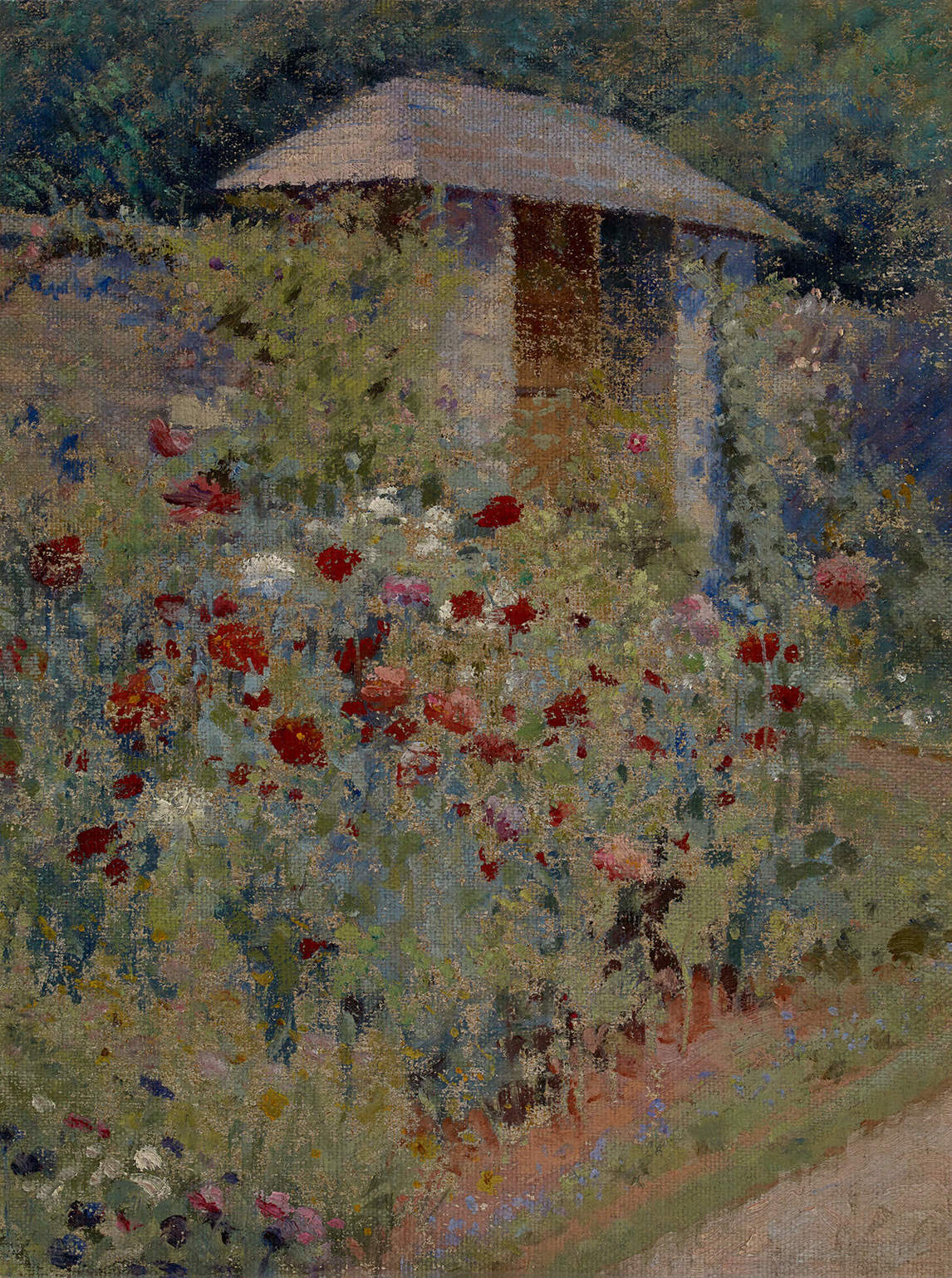

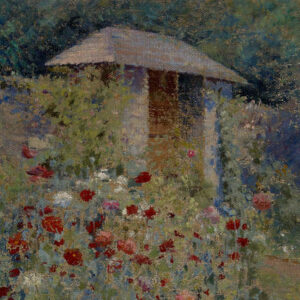

Hiester Reid’s inclusion of Impressionist painting strategies in her work can be also directly attributed to her study and travel in France. Garden paintings such as Hollyhocks, 1914, demonstrate her facility with painting en plein air, advocated by such artists as Claude Monet (1840–1926), Berthe Morisot (1841–1895), and the American-born Mary Cassatt (1844–1926). Hiester Reid’s A Poppy Garden, n.d., showcases not only her use of broken brushwork, but also the attention she paid to the ephemeral effects of light and atmosphere, as well as their influences on the colours of flowers and shadows, methods also practised by the Impressionists.

High Realism

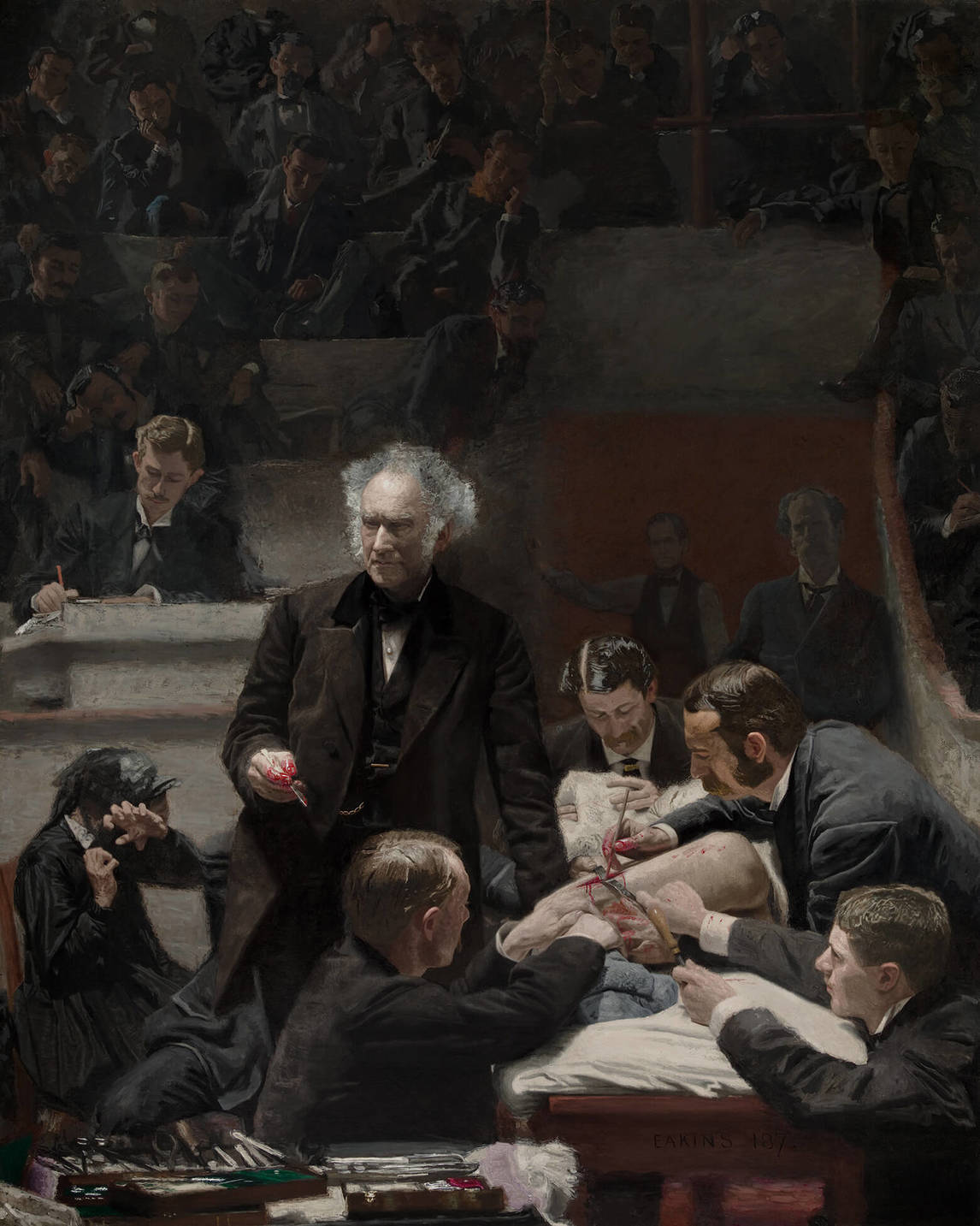

Hiester Reid’s still-life paintings garnered much praise and acclaim, particularly for their high degree of realism. This was a stylistic tendency she learned while studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and taking classes with Thomas Pollock Anshutz and Thomas Eakins. High realism, an art movement of the 1850s, featured exactingly descriptive painted representations. Hiester Reid’s adherence to this particular style indicates the influence of her studies with Eakins at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Eakins deployed what came to be known as “scientific realism” in his work. His painting The Gross Clinic, 1875, depicts a surgical lecture conducted under the supervision of Philadelphia-based physician Samuel David Gross. Eakins’s visceral depiction of the medical studies in progress in The Gross Clinic caused critics to recoil against the work, characterizing it as “too gruesome.”

The degree to which Hiester Reid expressed high realism in her still lifes is evident even in her later paintings of flowers, such as Study in Rose and Green, before 1917, and Past and Present, Still Life, 1918. Art critics like Hector Charlesworth (1872–1945) praised her for her achievements in the genre of high realism and for her floral still lifes in his review of her 1922 memorial exhibition published in Toronto’s Saturday Night magazine:

It was . . . one of her great gifts to be able to make the perishable beauty of flowers and fruit, permanent and fadeless, through her genius for the interpretation of delicate forms and services. Once a good many years ago, I met her in front of a fruit stall selecting peaches with a care that rather disturbed the vendor. “I don’t want them to eat” she explained, “Somehow a craving to paint the velvet texture of the peach overcame me.” And I recalled that forgotten chat the other day when I saw two or three still life pieces in which she had perfectly accomplished this desire.

Hiester Reid’s spouse George Agnew Reid also adhered to the principles of high realism, although he pursued its stylistic aims on a much larger scale. For example, for his monumental work Mortgaging the Homestead, 1890, George constructed a staged set of a “farm room” in his studio and posed models within it so that he could work from real life to paint the most realistic scene possible. Reid biographer Muriel Miller writes, “Because of its heavy brick walls, his . . . studio did not look unlike the interior of an old stone barn. Its rustic appearance captured his fancy, and both he and his wife realized its potential as a background for pictures re-creating pioneer life in Canada.” Given that both Reid and Hiester Reid consistently sold their paintings throughout the course of their careers, their training and subsequent efforts to adhere to the principles of high realism served them well.

The Aesthetic Movement

During her European travels, Hiester Reid visited many art galleries and museums, such as the Museum of Fine Arts in Madrid (now the Museo Nacional del Prado), studying different stylistic tendencies, and specifically those of the Aesthetic movement, an art movement that flourished in Britain during the 1870s and 1880s. Its leading proponents, such as artists James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Edward Burne-Jones (1883–1898), and poet and playwright Oscar Wilde (1854–1900), championed the concept “art for art’s sake,” desirous of a “cult of beauty” freed from the constraints of Victorian notions of morality. They envisioned their ideal encompassing all facets of daily life, from paintings and furniture to decorative arts and fashion.

Aestheticism was not simply an art style; it was also a lifestyle. Whistler collected things he believed to be beautiful and arranged them in his private residence to showcase their cultural and fashionable qualities. The arrangement of artistic collectibles, such as blue-and-white porcelains produced in either China or Japan, found in contemporary paintings by other Aesthetes—such as Monna Rosa, 1867, by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)—alongside furniture and flowers in one’s home was a direct reflection of this lifestyle approach. The appeal of art drawn from East Asian woodblock prints or porcelain, also known as japonisme, found its way into the artworks of many Aesthetes. In Hiester Reid’s case, paintings such as Chrysanthemums in a Qing Blue and White Vase, 1892, and Chrysanthemums: A Japanese Arrangement, c.1895, highlight her engagement in the Aesthetic movement’s collecting and painting practices.

Hiester Reid even captured her own Aesthetically styled interior in her Wychwood Park home, in A Fireside, 1912. The work depicts a fire-lit, warmly toned space defined by artfully arranged objects such as framed prints and paintings located on the wall adjacent to the fireplace, and flowers bearing a striking resemblance to Japanese orchids. Hiester Reid and her spouse George Agnew Reid moved into 81 Wychwood Park, a house they called Upland Cottage, in 1908. Designed by George Reid, the residence expresses the interests of the Aesthetic movement in its architectural eclecticism—a long, low horizontal layout, and groupings of leaded casement windows that blend in with the surrounding foliage and greenery.

Hiester Reid also produced Tonalist art, a painting style closely aligned with the principles of the Aesthetic movement, and one with which James Abbott McNeill Whistler was associated. This style was distinguished by artists’ use of soft, mostly dark colours to accentuate pictorial unity in their works, and it gained traction in North America between 1880 and 1915. Working in tonal harmony took great skill in that it required artists to distinguish forms using slight yet significant colour variations. This style reflected the artist’s keenly informed grasp of the techniques and methods needed to blend paints and subtly define forms for viewers. Hiester Reid’s work A Harmony in Grey and Yellow, 1897, specifically, and At Twilight, Wychwood Park, 1911, showcase the artist’s in-depth exploration of Tonalist art.

Hiester Reid embraced Aestheticism over the entire course of her artistic career, so much so that we can see evidence of its influence in much later work. Paintings such as Past and Present, Still Life, 1918, demonstrate that she continued to develop and test her skills. Here she uses shades so dark that patches of black contrast strikingly with the dried flora, the blue-grey sheen of the plate, and the wilted roses off to the lower right side. She also produced a great many works using coloured chalks, such as Flower Garden, c.1898. In this case, the medium allowed her to work en plein air and quickly jot down her impressions of the garden while standing in or around it out of doors.

The use of coloured chalks allowed her to work late into her life. In 1919 Hiester Reid had a heart attack, and although she survived, she often experienced severe attacks of angina afterwards and could no longer sit for hours at a time to paint. By the spring of 1921 she was often bedridden for weeks at a time. Despite her physical deterioration, she continued to produce art, an example of which is Cactus Dahlias, c.1919. The subject and the pastels indicate a hasty execution. She uses coloured lines to emphasize the spiky nature of the flowers; the shadows falling on both the bowl and tabletop could have been blended using her fingers.

Exploring Impressionism

As Hiester Reid’s career advanced, so too did her exploration of different artistic styles. Artists living in Canada such as William Brymner (1855–1925), Maurice Cullen (1866–1934), James Wilson Morrice (1865–1924), and Helen McNicoll (1879–1915) often learned about Impressionist work and techniques by travelling in European countries, and particularly in France, as Hiester Reid did. They also visited exhibitions, such as the one held in the Montreal gallery of W. Scott and Sons in 1892. In France, Impressionists such as Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, and Mary Cassatt sought to capture in paint the momentary, sensory effects of a scene—the impression captured by the eye in an instant—and so they painted en plein air. Other artistic strategies included loose brushwork to capture the ephemeral effects of sunlight and shadows.

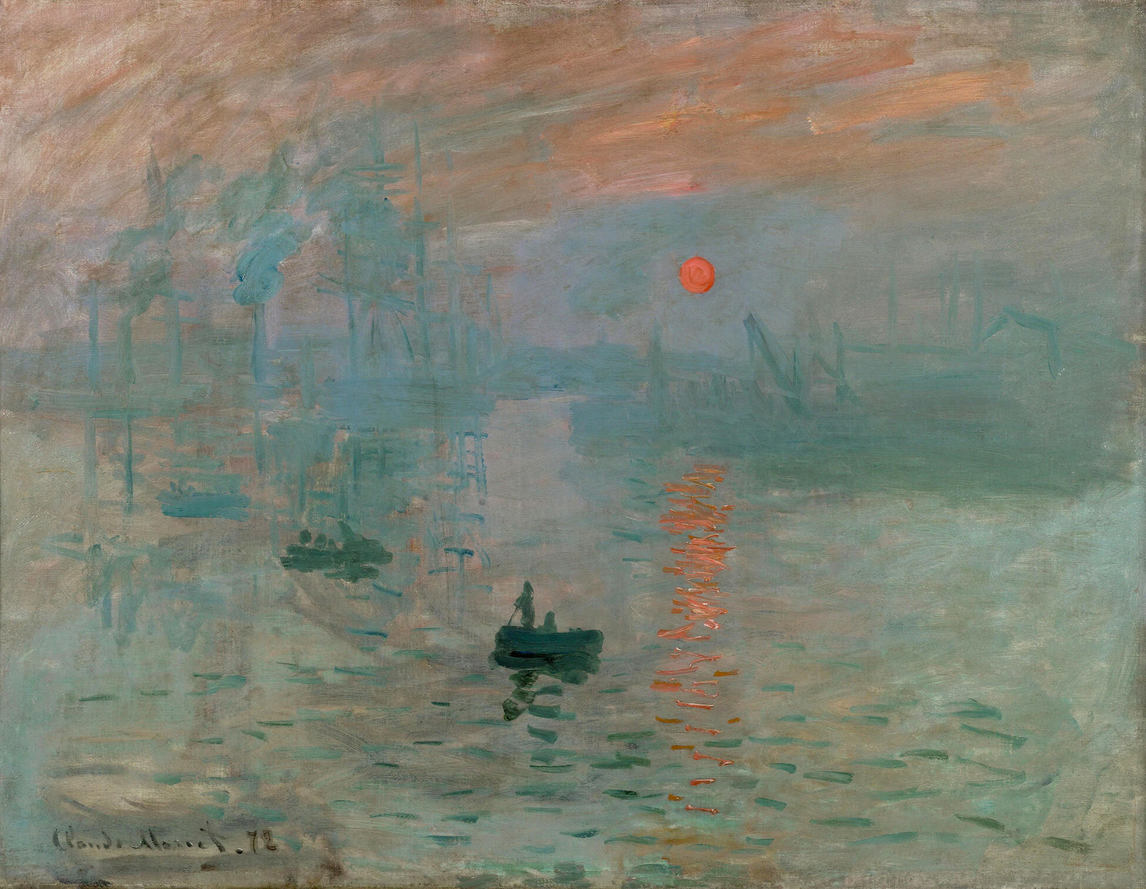

Hiester Reid’s work Moonrise,1898, is a far cry from her highly realistic floral still lifes, and entirely reflective of the French Impressionist influence on her work. In Moonrise, silhouetted trees and grass located in the extreme foreground of the picture plane frame the orange orb located just left of centre. In simplifying the forms using broken brush strokes and large patches of colour, Hiester Reid starkly compares the various forms to showcase the effects of moonlight. The work’s technical, stylistic, and compositional affinity to Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (Impression, soleil levant), 1872, demonstrates how Hiester Reid pushed her technical capabilities adroitly and skillfully, generating a diverse and sophisticated body of work. Her work Afternoon Sunlight, 1903, highlights her exploration of the effects of sunlight and the production of shadows in the foreground, contrasted against the sunlit buildings beyond the stone wall.

Though Hiester Reid applied Impressionist painting strategies in her work, ultimately the result was uniquely hers. As Carol Lowrey writes, “In Canada, the Impressionist tradition was not so much a movement per se, but a group of diverse painters responding to the aesthetic each in his or her own distinctive way. . . . Formal responses varied from artist to artist and, in many instances, were tempered by the artist’s commitment to academic ideals, as well as by his or her subject matter.”

Oil Painting

Hiester Reid made numerous strategic choices to distinguish both herself and her art as professional. By working primarily in oils she established her place in a long-standing commercially and critically lauded artistic practice. Most of her work was produced on small-to-medium canvases in oil paints. She did create some large-scale works, though, specifically three murals—one of which is Castles in Spain, c.1896. She also explored different media, using pastels in some of her preparatory works, such as Adirondacks, that she created between 1891 and 1917. For Hiester Reid these were minor forays outside the medium of oil.

Oil painting has a long history, dating back to the twelfth century. Over the course of the ensuing centuries, artists such as the Netherlandish painters Jan van Eyck (1390–1441) and Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750), Italian artist Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–c.1652), and American Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) all made art using oil paints. Oil paints are made by suspending powdered pigments in linseed or, in some cases, walnut oil. The resulting viscous medium takes a long time to dry, as compared to watercolour paints, made from pigments suspended in water that are typically applied to special absorbent paper so that they dry relatively quickly. As a result, artists can make changes to their work during the oil painting process. When the work is finished they can then smooth out its surface, eliminating the hand of the artist (evidence of brushwork or strokes) so that any indication of human interaction or production disappears. When these paintings are placed under lights in a home or gallery environment, the oil reflects the light: these images may appear to glow, making them even more lifelike.

Hiester Reid likely embraced oil painting because it was a commercially valued medium, highly sellable, and profitable. Much of her European travel was financed by the sale of her oil paintings. Painting in oils also signalled to a buyer that the artist had professional academic training. The medium of watercolour, in contrast, was often used by those pursuing art informally. As Pamela Gerrish Nunn explains, “Watercolour [was] the amateur’s medium par excellence thought by the conventional mind to be cleaner and easier to manipulate than oil. It was generally worked on a small scale, thus presenting a manageable challenge and flattering the conceit of modesty and dexterity in women’s activities.” Hiester Reid’s nearly exclusive work in oils underscores her conscientious management of both her practice and her artistic career. She created works that would appeal to and impress private art collectors and institutions alike.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements