Mary Hiester Reid (1854–1921) was a prominent figure in Canada’s art scene from the 1890s through the 1910s. Known predominantly for her floral still-life oil paintings, she achieved both commercial and critical success despite the patriarchal barriers of the day. Hiester Reid’s oeuvre captured the culturally sophisticated artistic movements of her time, such as Impressionism and Tonalist art. In 1922, the Art Gallery of Toronto exhibited her work in the first one-woman show to be held at that institution since its founding in 1900. A second solo retrospective exhibition of her work was held in 2000 at the gallery’s successor institution, the Art Gallery of Ontario, to showcase her historical importance.

Floral Aesthetics

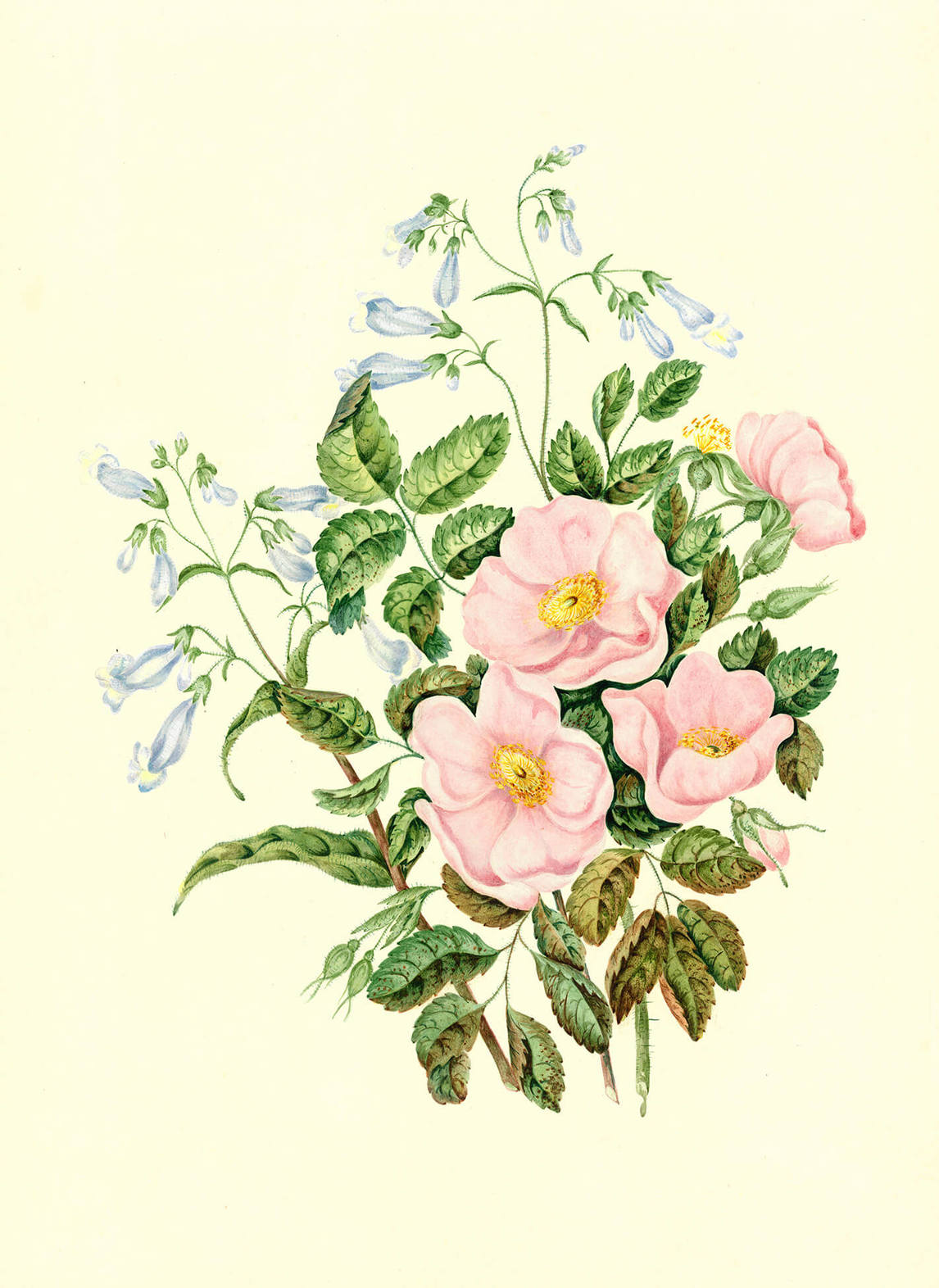

Although Hiester Reid painted various subjects during her career, such as garden vistas, moonlit urban and rural environments, and domestic interiors, she was best known and most praised for her artful depictions of flowers. Her floral still-life paintings distinguished her as an artist, earning her both commercial success and critical acclaim at a time when women were expected to explore art primarily as a domestic hobby. As art historian Pamela Gerrish Nunn explains, “The raw materials for flower-painting were eminently available to women in the domestic environment, and women’s pastimes and domestic skills were both commonly focused on flora, from making cut-paper flowers or embroidering handkerchiefs with tiny roses to arranging vases or nurturing a pot-plant in the rooms of a house.”

Hiester Reid’s subject specialization speaks not only to her marketing savvy but also to a longer history of women’s engagement with flower painting, pursued by individuals such as Dutch still-life painters Judith Leyster (1609–1660), Maria van Oosterwijck (1630–1693), and Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750); English artist Mary Moser (1744–1819); and perhaps most recognizably today, Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986). Like these artists, Hiester Reid started out in her career producing highly realistic works paying meticulous attention to minute details such as the individual petals of a chrysanthemum. But her extensive travels allowed her to absorb the influences of international art movements, such as Impressionism and Tonalism, which in turn had a deep impact on her work. As she progressed in her artistic career, Hiester Reid pushed the standards of floral still lifes, infusing them with contemporary stylistic traits such as broader brush strokes and impressive tonal variations to define the blooms, turning her still-life works into artfully arranged and Aesthetically informed settings.

In the eighteenth century, European art academies ranked flower paintings as a subset of the still-life painting genre, the lowliest genre in the academic painting hierarchy. The realistic details prized in floral works drew on the chief requirements of botanical illustrations. Such illustrations, with an emphasis on technical accuracy, were often included as teaching tools in eighteenth-century scientific studies. The paintings also enabled people to see and study blooms that grew in different parts of the world, which made these paintings quite marketable.

Though it was women who produced many of these illustrations, men often wrote the accompanying scientific treatises—a process that arguably separated the spheres of art and science into female and male ventures. Some of Hiester Reid’s Canadian predecessors who strove for scientific accuracy in their botanical works were Halifax artist Maria Frances Ann Morris Miller (1813–1875) and Ontario-based Agnes Dunbar Moodie Fitzgibbon Chamberlin (1833–1913), who illustrated two books on Canadian flora written by Catharine Parr Traill (1802–1899), Canadian Wild Flowers (1869), and Studies of Plant Life in Canada (1885).

Around the mid- to late nineteenth century, artists heeding the advice and theories of English critic John Ruskin (1819–1900) sought to infuse paintings of flowers with “modern force,” producing works that paid attention to “botanical accuracy,” while simultaneously incorporating “high art ideals.” Hiester Reid adhered to Ruskin’s assertion that an artist’s practice must be scientifically accurate, aesthetically pleasing, and poetic in nature. Her efforts to meet these exacting dynamics were noted by reviewers during her own time, as seen in her 1891 painting Chrysanthemums. In 1899 the pseudonymously named Lynn C. Doyle, writing for Toronto’s Globe, posited that “Mrs. Reid’s flower pieces will never lack for admirers, and for the best of reasons; she gives more than their mere likeness, something of its inner grace, or soul, for as one great Frenchman claimed, ‘everything in nature has a hidden, and, so as to say, mortal life.’”

An Independent Career

As a married and childless woman in the late Victorian and early Edwardian eras, Hiester Reid was able to actively engage with artistic pursuits and extensive travel and study, which underscore her efforts to foster her work and artistic career. Through selling her paintings at commercial galleries and to public arts institutions, she secured professional recognition, a collegial network, and steady financial support throughout her career. And even though until the late 1990s scholars suggested that Hiester Reid played mainly a supportive role to her artist husband George Agnew Reid (1860–1947), her cultivation of an autonomous artistic career is evident in her organization of her own solo exhibitions and studio visits for the public.

In 1920, for instance, Hiester Reid and five other artists, including Marion Long (1882–1970) and Harriet Ford (1859–1938), opened their studios to the public over the course of three consecutive December afternoons. Hiester Reid did help her husband with his studio visits, according to one journalist writing under the pseudonym Uncle Thomas, acting as “a very pleasant assistant to her husband in welcoming the throng that visited the studio to admire his latest and perhaps his greatest work[s],” but she also staunchly promoted her own work and provided public access to it independent of him.

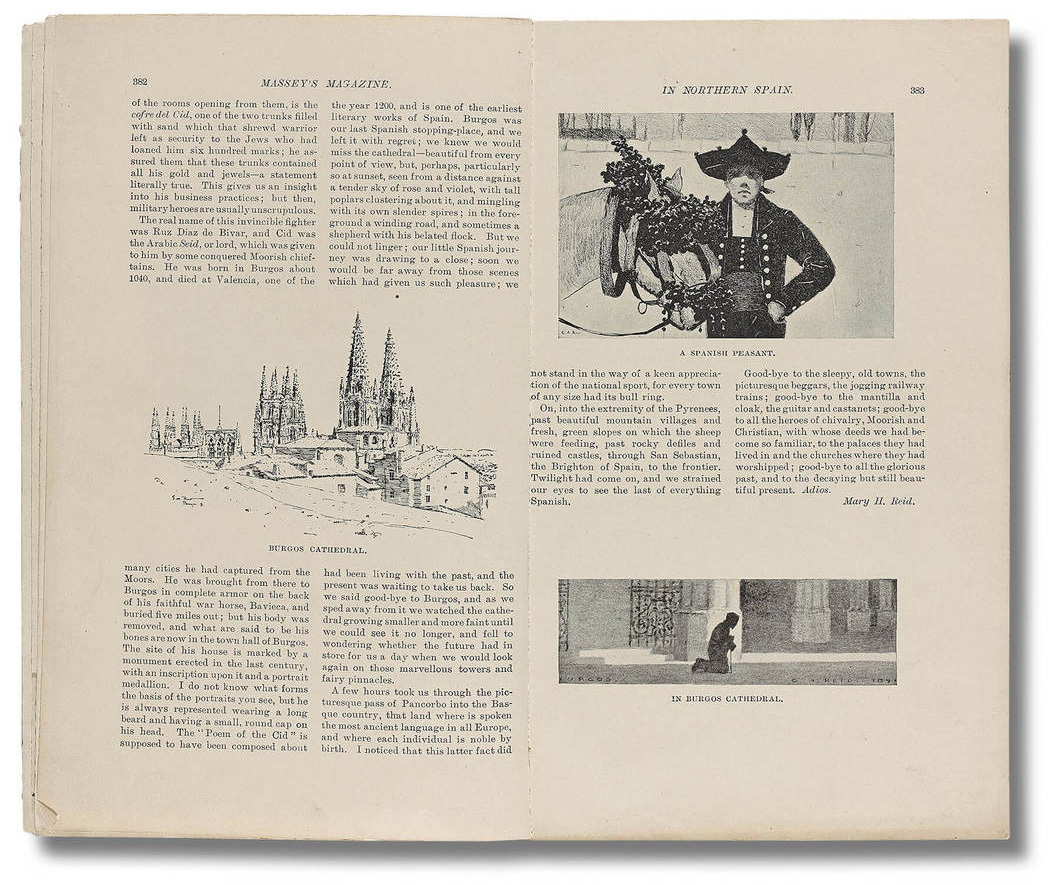

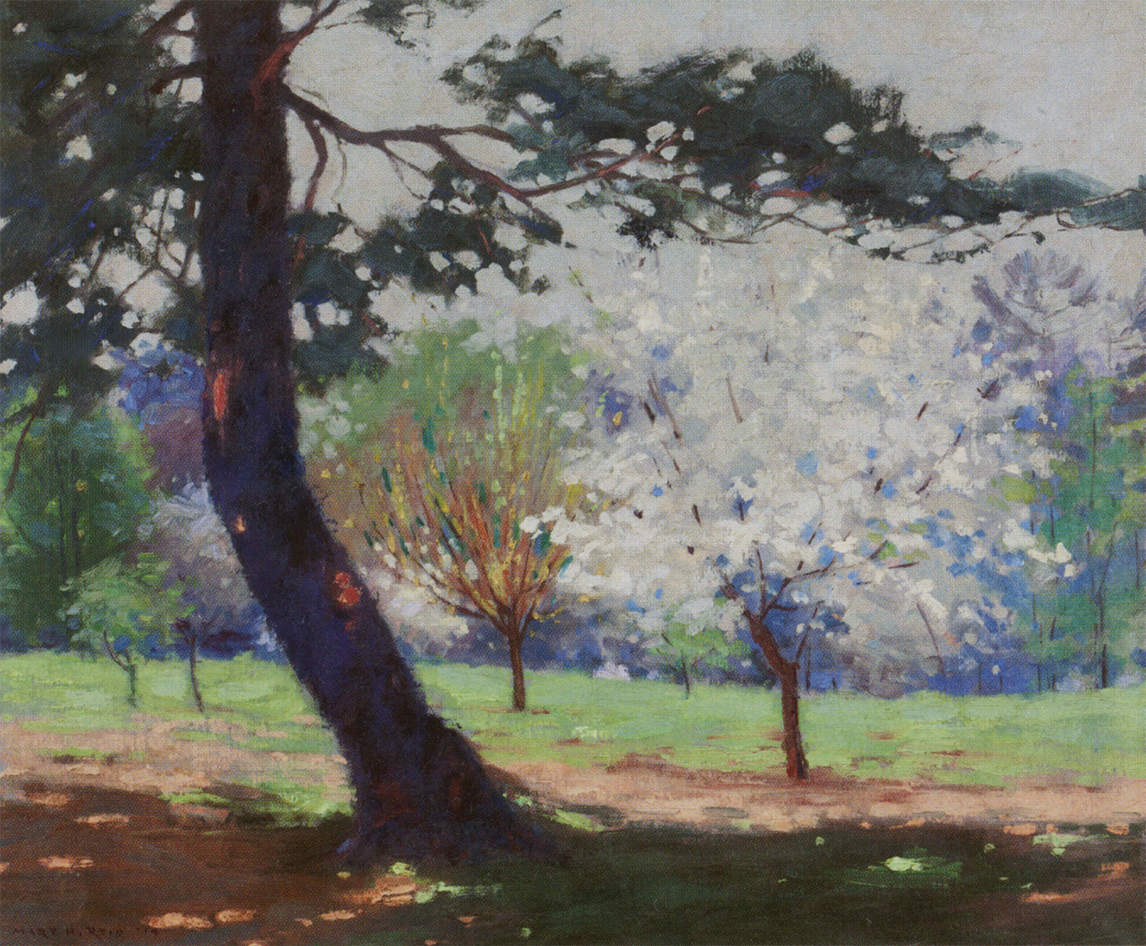

Hiester Reid and her spouse travelled extensively during their marriage, visiting Europe numerous times, in 1885, 1888–89, 1896, 1902, and 1910. She made it a point to carve out space for her own work. But her only published writings on art during her career are a series of three articles published in Toronto’s Massey’s Magazine about her European tour to Spain in 1896, which were illustrated by her husband. However, in defiance of social mores she published these travel articles under her given name, Mary Reid, instead of following the convention of adopting her husband’s entire name and publishing as Mrs. George Reid. Around this same time, she began signing her paintings using the initials of both her given and unmarried names alongside her married surname, “M.H. Reid,” as seen in Studio in Paris, 1896. Later, she used her given name with the initial of her unmarried name, “Mary H. Reid,” as seen in Morning Sunshine, 1913.

In the Massey’s Magazine articles Hiester Reid writes about how European travels such as hers offered artists ample opportunity to visit museums and historic sites, as well as multiple sketching possibilities. Despite the social conventions of the day, Hiester Reid had no misgivings about giving the appearance that she was sketching alone. In the third instalment of the Massey’s article series, she describes her encounter with a group of “fifteen or twenty young students” from Salamanca University as she sketched alone. “I was somewhat jostled,” she writes,

as they crowded around me to see what I was doing. I fancy that a woman sitting alone on the street, unless unmistakably a working woman, was an unaccustomed sight. How anxious they were to find out what language I understood: French, German and Spanish they tried, but I went on cheerfully with my sketch, occasionally waving them aside when they obstructed my view, and a little later I enjoyed their evident discomfiture when they discovered that I was not entirely alone; they fell back quite deferentially as we walked away. What a difference the presence of a man makes!

Here Hiester Reid proclaims for her readers how she refused to let social conventions stand in the way of her artistic pursuits. This determination served her well in the decades to come.

Professionalism and Feminism

A useful way to consider Hiester Reid’s work and career is to look at her work through the framework of the professional limitations imposed upon women in the Canadian art world in the mid-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This approach has been decisively advanced by the Canadian Women’s Art History Initiative, founded in 2007, and in its subsequent publication of an edited collection of essays, Rethinking Professionalism: Women and Art in Canada, 1850–1970.

In the preface, editors Kristina Huneault and Janice Anderson explain, “The social formation of professionalism has been particularly influential in the cultural field, dividing amateurs from ‘serious’ artists and underpinning claims for increased status and support for the arts. It is also a formation of special relevance to women. At professionalism’s doors may be heaped both the most outrageous and discriminatory practices of the past and many of women’s most impressive cultural achievements.” As Susan Butlin explains, professional artist societies prohibited women’s full participation by placing them in special categories. Britain’s Royal Academy of Arts barred women from membership throughout the nineteenth century. Even though at the time of its founding in 1768 it included two female members, Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807) and Mary Moser (1744–1819), it refused to admit any more women as members until 1922.

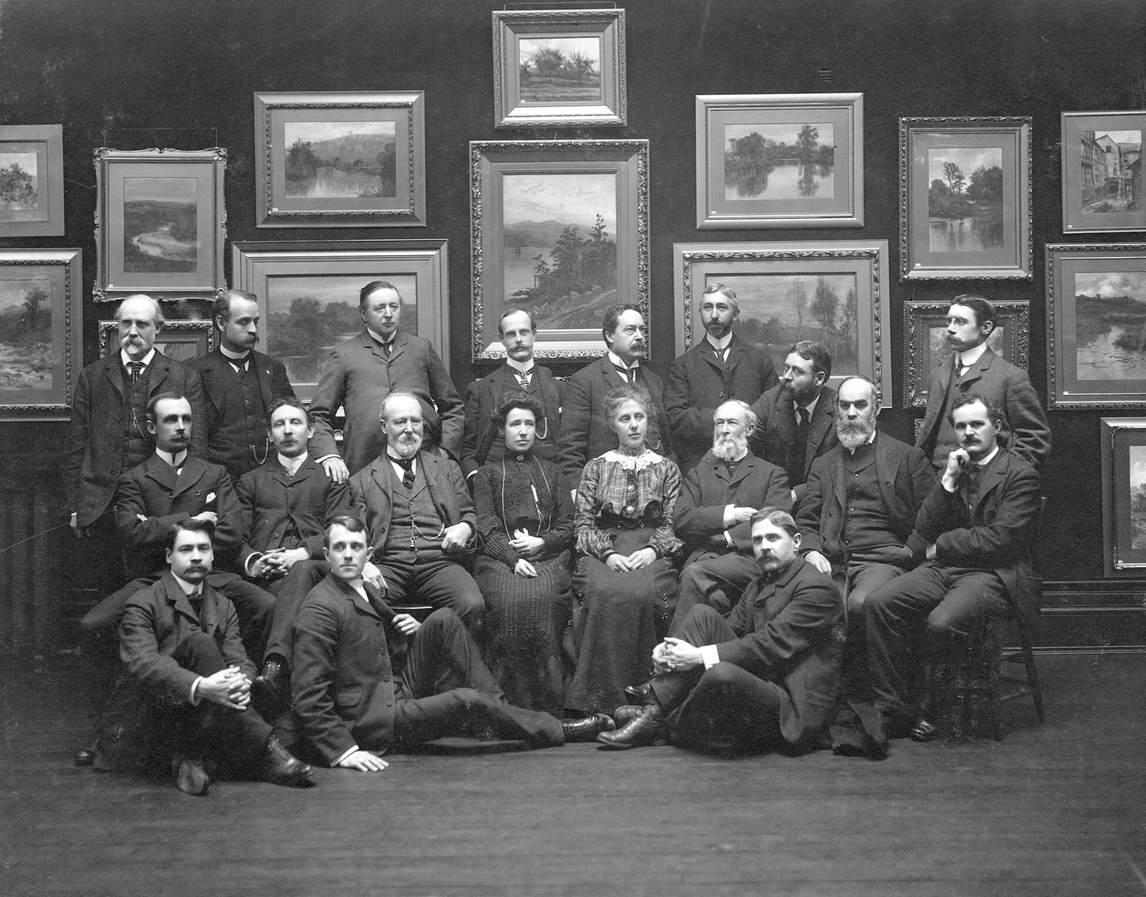

Hiester Reid employed several techniques to distinguish herself as a professionally trained, and thus professional, artist. She studied and taught at arts academies across North America and Europe, joined numerous artist-run organizations, such as the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA), and submitted paintings to these organizations’ annual exhibitions. Such activities and ventures, however, did not automatically afford her the distinctions available to her male peers, including her artist husband, George Agnew Reid.

For example, in 1893 Hiester Reid was elected to be an associate member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA). However, although their artistic careers had begun around the same time, her spouse had been made an associate member eight years earlier, and by 1890 he had become a full member, a status Hiester Reid was never afforded. When it was founded in 1880, the RCA elected artist Charlotte Schreiber (1834–1922) as a founding academician member. Schreiber was the last woman named as a full member until 1933. From 1880 to 1913, “women artists were barred from full academician status and could only advance to the level of associate upon election by an exclusively male group of academicians.”

This meant that although women could publicly proclaim their membership by including the initials “ARCA” after their names, the initials also denoted women’s lower rank in the organization. The gender-biased policies of the organization not only favoured male artists, they also meant that women could not use the full membership acronym, “RCA”; nor could women participate in or hold positions on the executive council or attend members’ meetings. In 1913 the RCA removed the restrictions from its constitution barring women from joining the executive council and attending business meetings, but it was not until 1933 that the RCA permitted women to be elected as full academicians; the second woman artist in the association’s history to be granted entry that year was Marion Long (1882–1970).

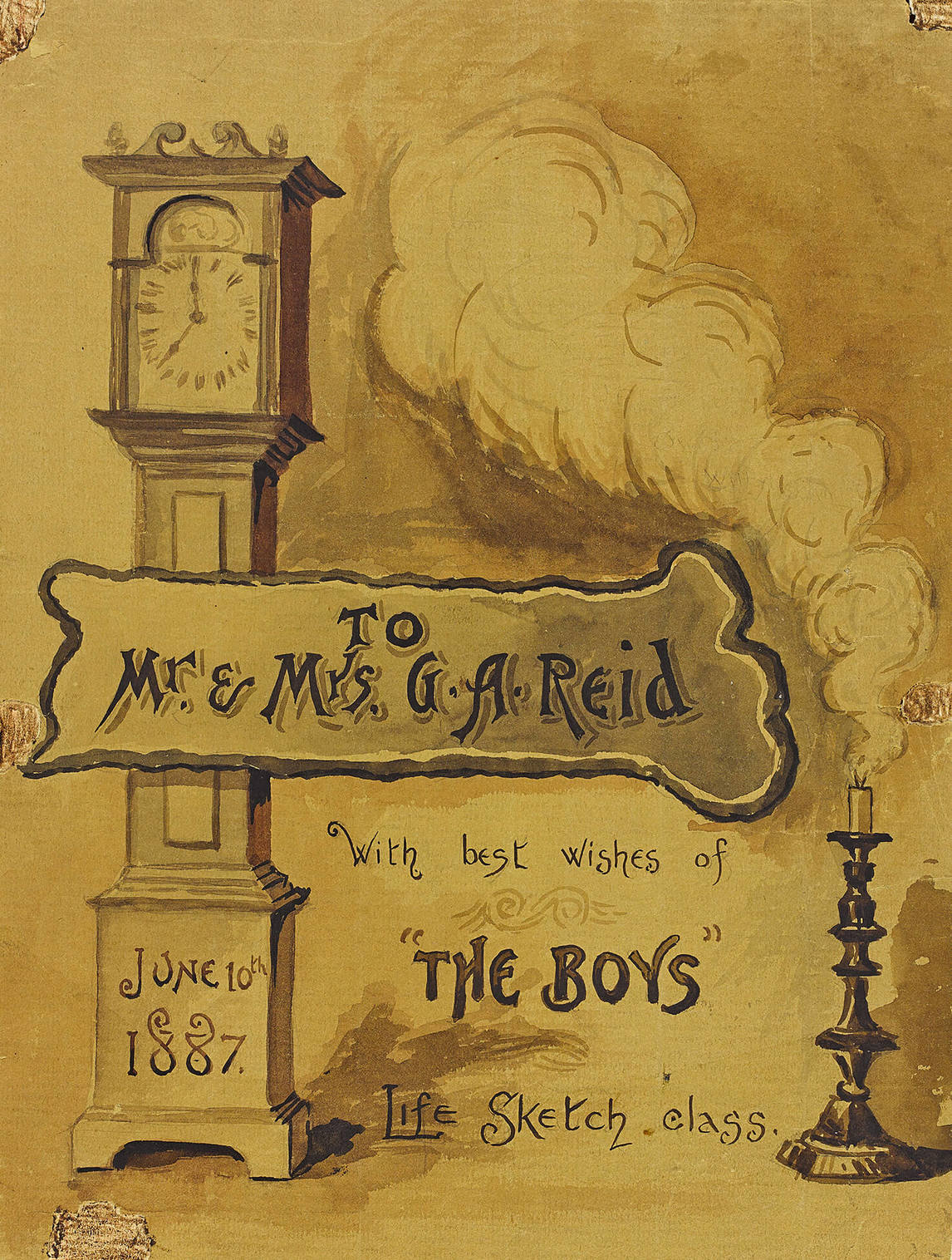

George Reid, however, appears to have had tremendous respect for his wife’s talent, her career, and her work. The spouses organized a number of joint exhibitions, such as one at the Toronto-based auction house Oliver, Coate & Co., in May 1888. At the show’s conclusion the works were sold to the highest bidder. George Reid kept one of the sale catalogues and preserved it in his scrapbook. In it were listed the titles of the artworks but not who made which one. George jotted down the initials “M.H.R,” under thirteen of the ninety-three works listed, distinguishing for the record his wife’s art production and sales.

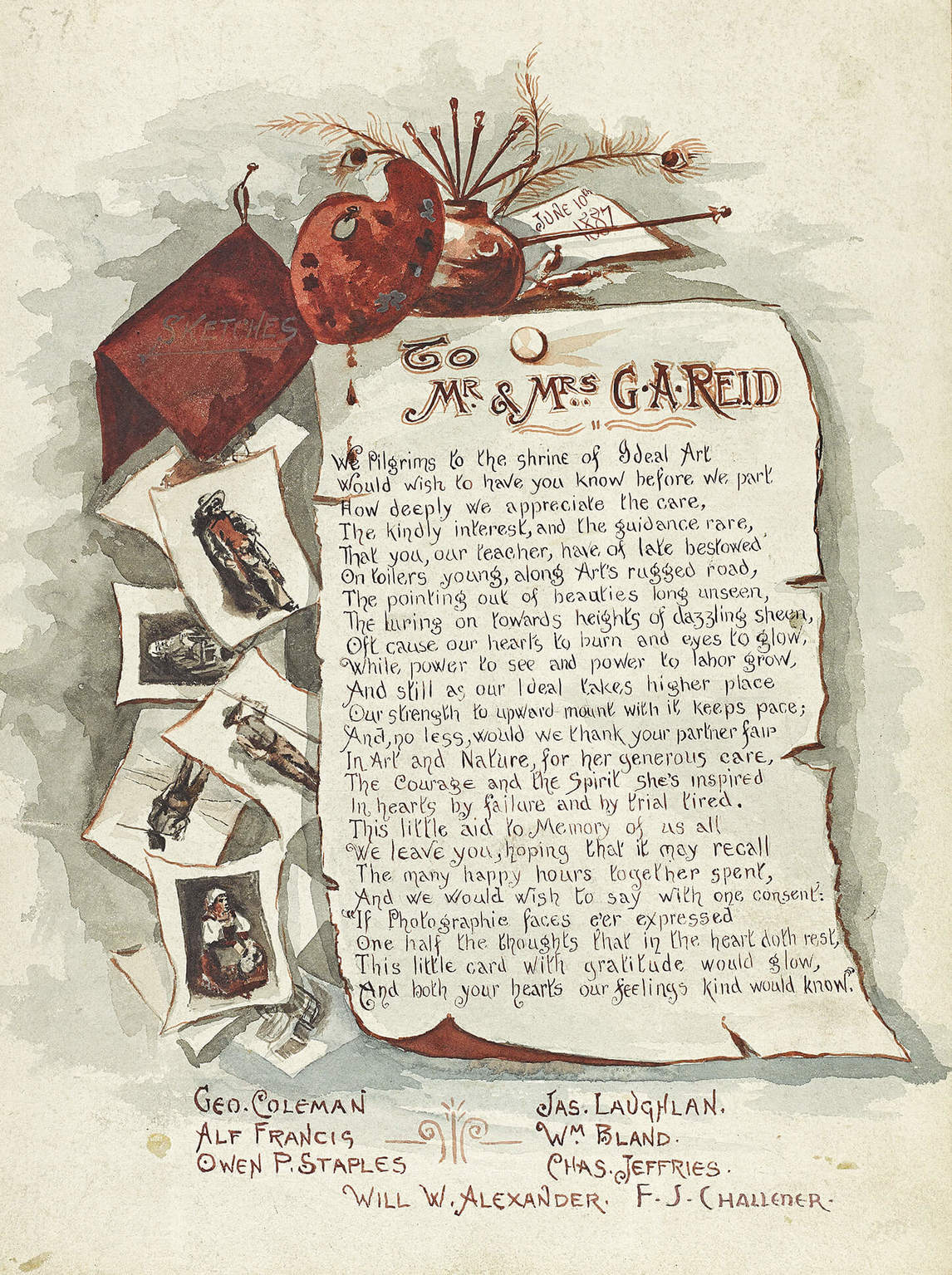

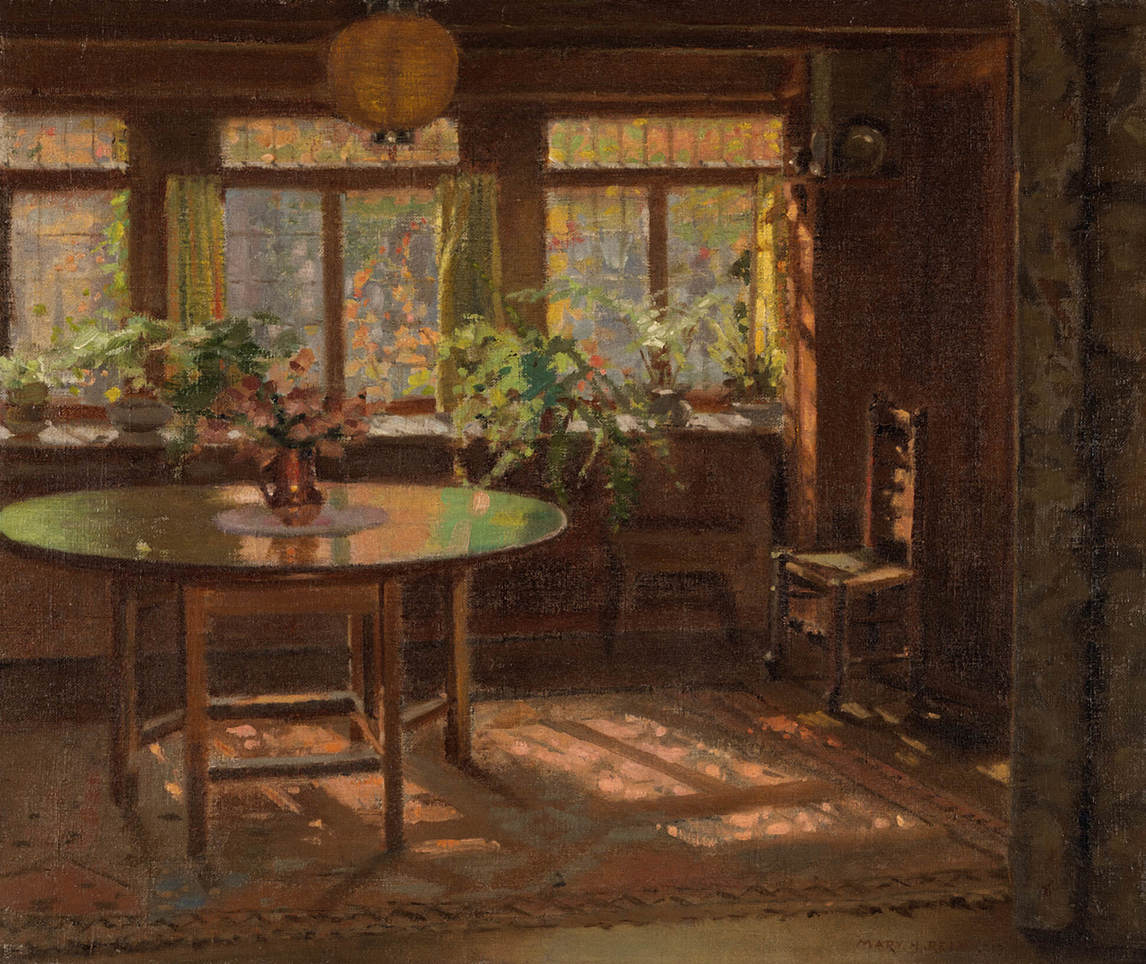

And when George designed their home, Upland Cottage, which they moved into in 1908, he put in a separate studio for each of them. Hiester Reid painted her Upland Cottage studio in her work, A Fireside, 1912. The couple’s art students also acknowledged both Hiester Reid and her spouse as evenly matched partners in the studio classroom, addressing thank-you notes and sketches to both of them. Undoubtedly, they both played equally significant roles in their joint teaching endeavours.

In Hiester Reid’s day, women often identified themselves as professional artists by including their unmarried names in their signed artworks. Artists such as Laura Muntz Lyall (1860–1930) and Gertrude Spurr Cutts (1858–1941) did exactly that, perhaps a silent refutation of the sexism that marginalized their work. When signing her works, Hiester Reid often included either her unmarried name “Hiester” or, more frequently, the initial “H.” In the case of her work Early Spring, 1914, she also uses her given name, so it reads in its entirety “Mary H. Reid.” By using their first names or the initial of their unmarried names, Hiester Reid and these women forthrightly proclaimed and distinguished themselves as independent and accomplished artists.

Acknowledging the barriers that Mary Hiester Reid navigated—be they social, administrative, economic, or political—so that she could wholly engage, operate, and succeed in Canada’s art world is an important step in considering her artistic legacy. Understood in the context of the late Victorian and Edwardian periods, her achievements are most effectively recognized as a woman’s strategically productive forays into places and organizations designed to exclude her. What is more, she produced and sold paintings to enhance the beauty of people’s homes. As M.O. Hammond (1876–1934) wrote in 1930 as part of his published series in Toronto’s Globe newspaper, “Leading Canadian Artists,” Mary Hiester Reid’s “pictures sold rapidly and she is remembered in scores of homes and galleries by the fresh note of colour and sweetness which she gives from her corner of the wall.” She went on to capture her own artistically informed interiors in works such as A Fireside, 1912, and Morning Sunshine, 1913, revealing expressively how Canada’s foremost adherents of the Aesthetic and Arts and Crafts movements designed and decorated their own private spaces.

Nationalism and Exclusion

Hiester Reid was celebrated during her lifetime, and her posthumous 1922 memorial exhibition at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario) garnered both popular and critical acclaim. After visiting this exhibition, Hector Charlesworth (1872–1945), a Toronto-based journalist and arts commentator, wrote of Hiester Reid’s work in glowing terms:

Mrs. Reid’s sense of the colour nuances of nature was as distinguished as that of a [Claude] Debussy in the mystical domain of musical tones. But as a matured technician it was her wonderful tactile sense that was her most impressive gift. . . . The development of tactile appreciation, and of a sense of the minute beauties of reflections, affords a very deep pleasure even to those endowed with the gift of transferring it to canvas. . . . In these her mastery in the true interpretation of atmosphere is best revealed.

This quality is expressed fully in her work A Harmony in Grey and Yellow, 1897.

Nonetheless, Hiester Reid’s legacy was eclipsed soon after her memorial exhibition. It was not until the late 1990s that her work was seriously considered by scholars, and then featured in the context of the 2000–1 retrospective exhibition entitled Quiet Harmony: The Art of Mary Hiester Reid, again at the Art Gallery of Ontario. So, why did her work slip into obscurity between the mid-1920s and 2000s?

The mid-1920s witnessed a shifting of taste regarding “national” art, giving way to the Group of Seven’s ascendency in the public’s estimation in Canada and abroad. In 1924 and 1925, the National Gallery of Canada organized two exhibitions of Canadian art for the British Empire Exhibition. Though the 1924 exhibition featured a wide range of works, including Hiester Reid’s Morning Sunshine, 1913, the British critics reserved most of their praise for the “nationalist and modernist agendas within images of nature depicted as wilderness,” and particularly those images by the Group of Seven, which had formed and held its first group exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario in the spring of 1920. The group’s work, characterized by monumental canvases featuring robust, unpeopled landscapes, was perceived as effectively capturing a quintessential Canadian identity, eclipsing “the more romantic, idealized work by artists such as [Hiester] Reid.”

Another reason for this eclipse of the artist’s work might simply be sexism in action. Art historian Linda Nochlin (1931–2017) posed an insightful question in her 1971 article, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Nochlin made a case that the systemic exclusion that runs through art history has caused female artists to be removed from the canon. As critical and public attention became focused on the Group of Seven’s bold interpretations of what art historian Newton MacTavish in 1925 referred to as “the buoyant, eager, defiant spirit of the nation,” awareness of Hiester Reid’s work and achievements waned, and she was not written about as frequently or extensively.

Regardless, the aesthetic ideals, technical skills, and remarkable achievements showcased by Hiester Reid’s career are a testament to a highly accomplished and insightful artist. She was an artist who keenly navigated through the sociocultural restraints of her time, while demonstrating how future female artists might steer their practices in the future.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements