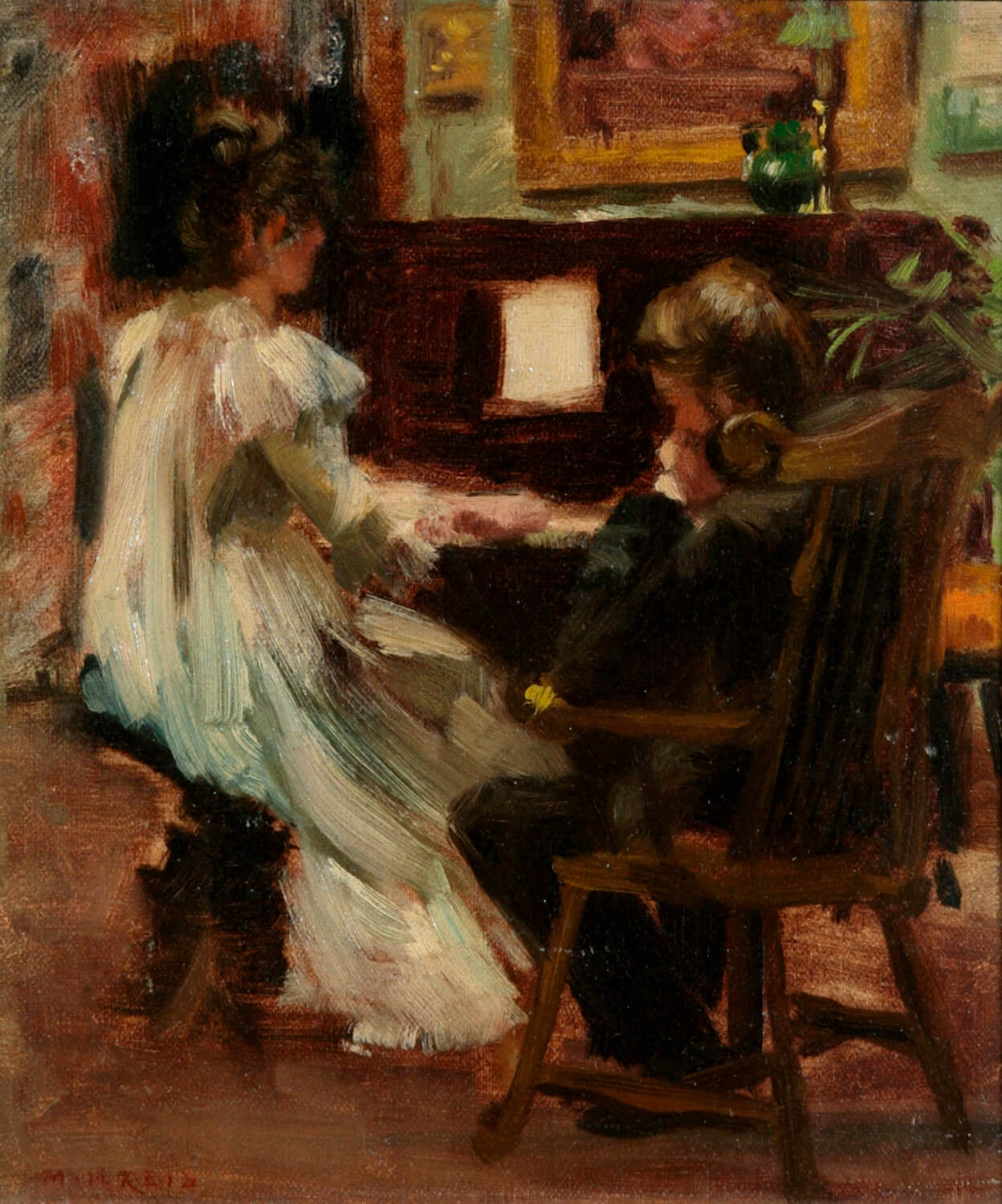

Study for “An Idle Hour” c.1896

Mary Hiester Reid, Study for “An Idle Hour,” c.1896

Oil on canvas, 23.2 x 20.3 cm

Museum London

In Study for “An Idle Hour,” Hiester Reid depicts artist Henrietta Moodie Vickers (1870–1938) sitting in front of a piano with her back facing the viewer, face almost in profile, and right hand visible as it lies on the keys. Painter Frederick Challener (1869–1959) sits in a chair off to Vickers and the viewer’s right, resting his head on his fist, his arm bent at the elbow. Challener’s pose suggests to contemporary viewers that his attention is waning, but a journalist of the day described the figure as “drinking in the music.” Given Hiester Reid’s renown for her many highly finished floral still lifes, the painting is a rare example of the artist’s figural work. It is uncommon for such a work to be found in a public collection. This painting also demonstrates the sophistication and attention she paid to smaller preparatory works most likely used to produce larger finished works for sale.

The amount of work Hiester Reid painted for commercial sale suggests that there may be more figural artworks to be found in private collections. However, few figural paintings were featured in her 1922 memorial retrospective exhibition. Of 308 works listed in the 1922 catalogue, only twelve were listed under the heading “paintings of figures,” one being #256, The Haymaker, undated and now lost. The 2000–1 exhibition Quiet Harmony: The Art of Mary Hiester Reid featured forty-five works of which only five included figures. Except for At the Piano, c.1896, these few figural works were loaned to the exhibition by private collectors. Some of Hiester Reid’s figural work located in public art collections includes Study of a Head, n.d., in the Art Gallery of Alberta, and Nude Study, n.d., in Museum London.

Brian Foss notes that although Hiester Reid spent eleven months during 1883–85 taking life classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, she produced “only a handful of figure pictures.” It is significant that, though the artist received acclaim for her flower paintings, reviewers seemed more ambivalent about her interiors featuring figures. One critic even implied that Hiester Reid should continue to work in the genre she was best known for by plainly stating, “Mrs. Reid is much more successful with flowers and still life than with figures.”

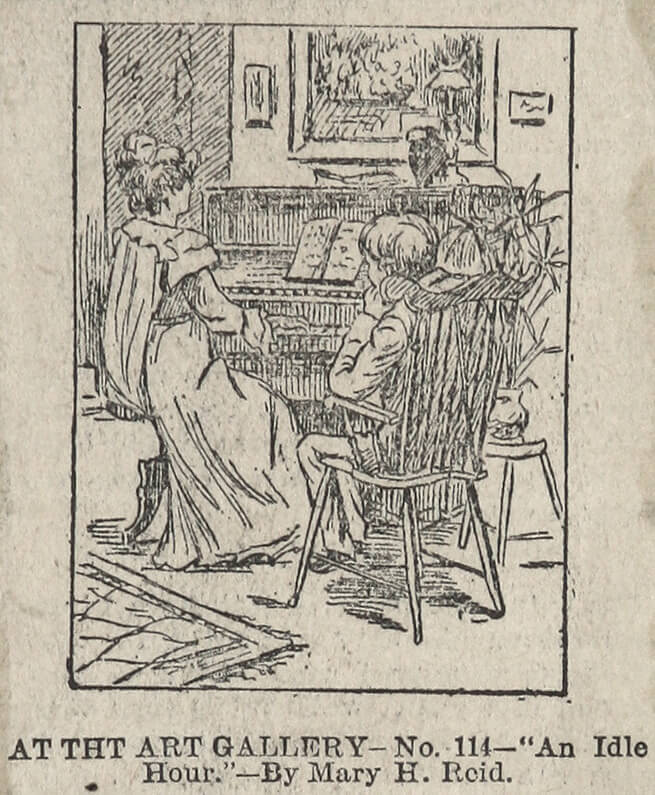

Some scholars believe Study for “An Idle Hour” to be a study for a larger piece because of its sketch-like qualities. The woman’s dress is rendered with broad visible brush strokes, and the entirety of the lowest portion of the work and the far right side are roughly defined by open brown sections of flat colour, with red sections interspersed along the top left corner. This analysis gains credence when we consider an illustration of a work exhibited by Hiester Reid, and titled An Idle Hour, that the Montreal Herald reproduced in its coverage of the annual exhibition at the Art Association of Montreal (later Montreal Museum of Fine Art). That illustration contains a carpet or tapestry in the lower left corner, framed pictures hanging on the wall above the piano in the middle ground, and two pieces of sheet music on the piano itself, details not included or only hinted at in this painted work.

In 2013 this work was featured in the National Gallery of Canada exhibition Artists, Architects and Artisans: Canadian Art 1890–1918. In the accompanying catalogue, art historian Laurier Lacroix writes that the painting captures “the particular atmosphere of intimacy associated with listening to music at home.” He was able to identify the two figures as friends of Hiester Reid because he had seen the back of the work. There, written in ink by artist Mary Wrinch Reid (1877–1969)—the second wife of George Agnew Reid (1860–1947), whom he married after Hiester Reid’s death—were the words “Note—the figures are portrait sketches of / Henrietta Vickers (Canadian artist) / and Frederick S Challener RCA / Painted in the Reid Studio.” Vickers was a still-life painter and sculptor who studied at the Ontario School of Art and Design (now OCAD University) and privately with George Reid. Both Reid and Hiester Reid used Vickers as a model in their works. A granddaughter of the writer Susannah Moodie, Vickers left Canada in the mid- to late 1890s, living first in France and then in Tangiers, Morocco. To date, it is unknown whether she ever returned to Canada, but she did exhibit artwork in the annual Ontario Society of Artists exhibitions from 1900 to 1904. Hiester Reid’s work therefore seems to raise more questions than it answers.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements