Mary Hiester Reid (1854–1921) was a trailblazing artist who steadily gained critical and commercial acclaim in oil painting, especially her sophisticated floral still lifes. Hiester Reid’s rigorous training in the academic style of high realism included studies at Philadelphia’s School of Design for Women, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the Académie Colarossi in Paris, France. Throughout her life she explored movements such as Aestheticism, Impressionism, and Arts and Crafts, and painted works filled with tonal intricacies and a wide range of colour. A prolific teacher of women artists in particular, Hiester Reid was dedicated to the advancement of arts education in North America. After her death, in 1922 the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario) hosted a large retrospective exhibition—the first one-woman show held at that institution since its founding in 1900.

Early Years

Born on April 10, 1854, in Reading, Pennsylvania, Mary Augusta Hiester was the younger of the two daughters of Caroline Amelia Musser and physician Dr. John Philip Hiester. Both her parents were of German heritage. Her father’s family arrived in the United States in 1832, and her mother’s family immigrated prior to the American War of Independence (1775–83) and settled mostly in the state of Pennsylvania. Mary Hiester’s father died a few months after she was born.

Mary Hiester Reid in her Paris studio at 65 Boulevard Arago, 1888–89, photograph by George Agnew Reid.

Mary Hiester Reid in her Paris studio at 65 Boulevard Arago, 1888–89, photograph by George Agnew Reid.

Hiester spent her childhood in Reading, a manufacturing town located approximately ninety kilometres northwest of Philadelphia. In later life she recalled aspects of a seemingly affluent childhood marked by drives in the country. In 1863, because her mother was suffering from “congestion of the lungs,” the family moved to Beloit, Wisconsin, to live with their cousin Harry McLenagan.

Reflecting on her time in Beloit in a 1910 Toronto newspaper interview with journalist Marjory MacMurchy, Hiester described the town as “favourable to the growth of spirit which was to care for beauty. The people . . . read much and talked of books, lived simply and had for their heroes men and women of high ideals and generous sacrifices.” And so, as MacMurchy puts it, “During these years the artist chose to be a painter. She always expected to paint, is the simplest way of putting it.” When her mother died in November 1875, Hiester returned to Reading where she stayed with another cousin, John McLenagan, and his family. Her sister, Caroline, chose instead to sail for Paris, France. While living abroad, Caroline converted from the Hiester family’s Lutheran faith to become a member of the Roman Catholic Church and later became a nun. The two sisters remained in contact by exchanging letters, and later, after Caroline had moved to Spain, Mary travelled there to visit numerous times.

Training and Travels

Back in Reading, Hiester determined that “the time had come for serious [artistic] study,” and so she moved to Philadelphia to attend the School of Design for Women from 1881 to 1883. Then, while teaching at a girls’ school, she studied part-time from 1883 to 1885 at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, an institution founded in 1805 by her relative George Clymer (1739–1813), a signer of the Declaration of Independence. At the Academy, Hiester took classes taught by award-winning portraitist Thomas Pollock Anshutz (1851–1912) and realist painter Thomas Eakins (1844–1916). In Hiester’s early canvases, such as Chrysanthemums, 1891, her attention to high realism, an art movement of the 1850s that prioritized exactingly descriptive painted representations, shows the influence of her studies with Eakins at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

After studying art in Paris, Eakins had returned to America intent on “develop[ing] a thorough knowledge of [human] anatomy and form in his students.” At this time, both European and North American art academies prohibited women from producing life studies based on nude figures, and particularly the male nude. It was believed “to be unsuitable for them.” Eakins’s “radical teaching method[s]” eschewed social conventions to provide all his students—men and women—equal access to artistic studies and practices. In January 1886 Eakins brought in a male model for the female students to draw, and then removed the model’s loincloth. News of this incident spread quickly throughout the Pennsylvania Academy and ultimately resulted in the board of directors requesting and receiving Eakins’s resignation in February.

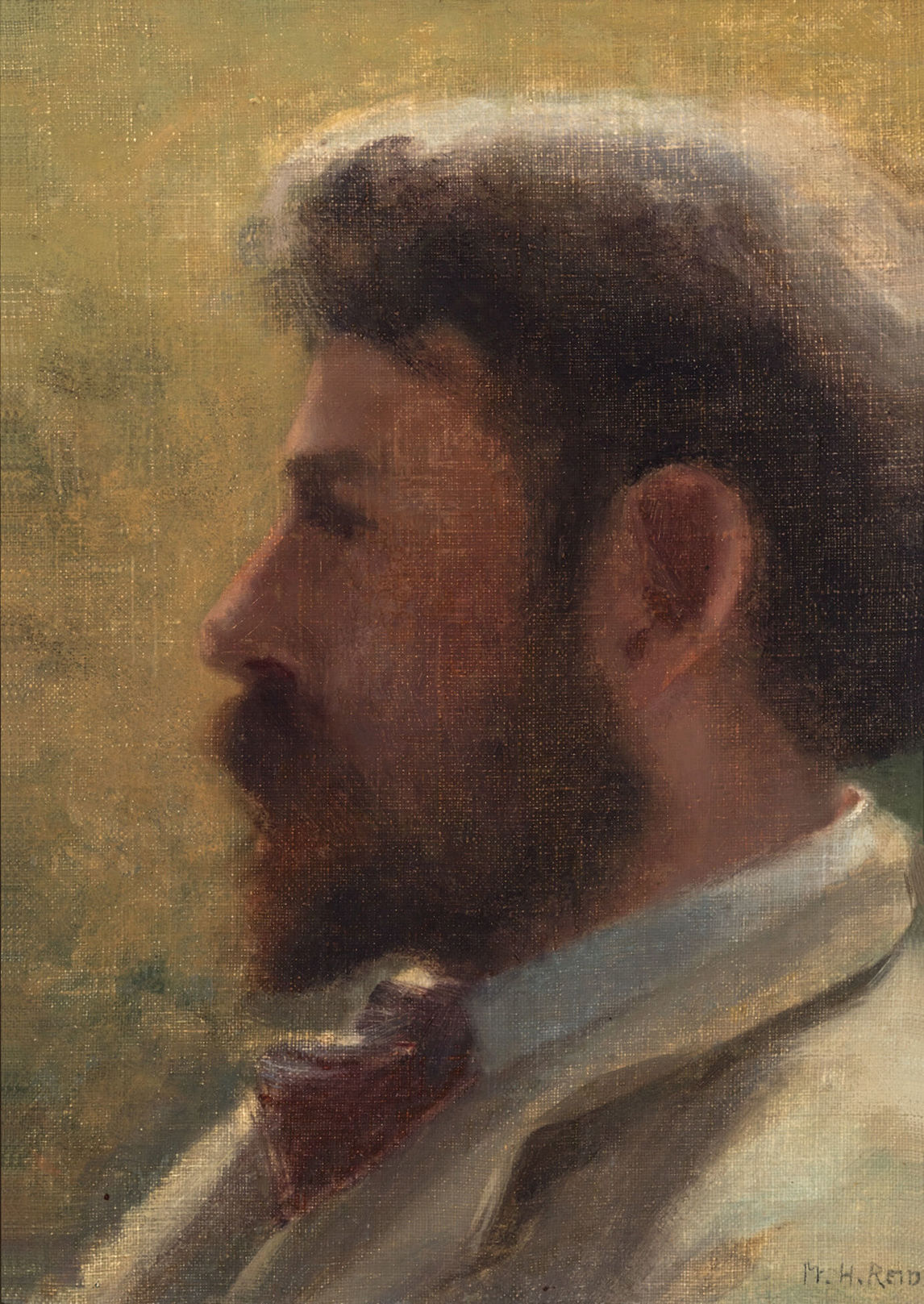

In her first few months at the Academy, Hiester met a fellow student from Canada, George Agnew Reid (1860–1947). The two artists went on numerous sketching trips together and got to know each other. As Reid biographer Muriel Miller explains,

Mary [was] the darling of the campus. She had sparkling brown eyes, arched black eyebrows, a dusky complexion with high colouring and black curly hair. Even so, it was her vivaciousness more than her beauty which made her so popular with her fellow students. . . . [Their] school sketching trips . . . gave [Reid] the opportunity to single out the beautiful Mary Hiester on their expeditions. Eventually, he worked up the courage to ask the popular Miss Mary Hiester to go sketching with him alone. After that, it had become a habit for them to work together and, [in the winter of 1883–84], Mary invited Reid to go home with her to Reading for a weekend sketching on the beautiful Schuykill [sic] River. That visit, by [Reid’s] own estimation, marked a point of departure in his [personal] life.

Reid eventually proposed, and in May 1885 the two married in St. Luke’s Church in Philadelphia. They honeymooned in Europe for four months, visiting London, Paris, Italy, and Spain. In Málaga, Spain, Hiester Reid visited her sister, Caroline, who would later become mother superior of a Spanish convent.

This trip marked the beginning of a series of extensive travels for Hiester Reid, taken both for pleasure and for artistic study. In Paris, Hiester Reid enrolled at the Académie Colarossi, taking “costume-study and life classes” under Joseph Blanc (1846–1904), Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret (1852–1929), Gustave Courtois (1853–1923), and Jean-André Rixens (1846–1925). She returned there to study in 1896, when she and her spouse toured Gibraltar and Spain.

Hiester Reid wrote about this 1896 trip in three articles published in Toronto’s Massey’s Magazine in 1896 and 1897, and George Reid produced the accompanying illustrations. Notably, in all three articles, the author-artist used her given name, Mary Reid, suggesting that she preferred this byline to the then-conventional married form of address, Mrs. G. Reid. As Hiester Reid’s sole published writings beyond her will, these articles provide vivid and valuable descriptions of the various sites, museums, and artworks she visited; they also explain how such travels benefited artists living in Canada.

Recounting her visit to the Museum of Fine Arts in Madrid (now the Museo Nacional del Prado), Hiester Reid notes her appreciation of Italian Renaissance artists Raphael (1483–1520), Titian (c.1488–1576), Tintoretto (c.1518–1594), and Paolo Veronese (1528–1588), the Flemish Baroque painter Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), as well as the Spanish master Diego Velázquez (1599–1660). Proclaiming the value of such travel to artists, Hiester Reid writes:

A journey to Madrid is worth all the expenditure of time and trouble it requires, for to see [these works] is an education one cannot afford to miss. The combination of freedom of handling with perfect tone and beauty of colour has certainly never been equalled; some of [James Abbott McNeill] Whistler’s, some of [John Singer] Sargent’s canvases approach these, but in the former, one so often finds either a lack of colour, sometimes called a “refinement of colour,” or a certain crudeness, and in the latter, a suggestion of paint which one never feels in Velasquez [sic]. His painting is robust, with no affectations; realistic, yet with infinite delicacy of modelling; there is probably nowhere a finer portrait picture than the group known as Las Meninas, full of character, faithfully portraying the period, even to the dwarfs and dogs, yet giving us a picture, which in itself, without connection with historical personages, must always be satisfying to look at.

In this passage, and throughout all three articles, Hiester Reid demonstrates her artistic training, fluidly referencing the names and works of Renaissance and Baroque masters and clearly articulating the techniques of her American artist contemporaries, John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) and James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903). In describing the museum visit as “an education,” Hiester Reid distinguishes herself as a knowledgeable, professional artist committed to pursuing further studies abroad.

Artist as Teacher

Following their four-month-long European honeymoon in 1885, Hiester Reid and her husband George Agnew Reid returned to North America and set up a studio at 31 King Street East in Toronto. As practising artists, they not only produced and sold artworks, but also managed a “joint teaching studio” where both taught private classes. Settling in Toronto, the couple chose to locate themselves in what would quickly become, by 1900, the province’s “largest professional art scene.”

During the early to late nineteenth century, artists born in Canada typically went abroad to study at established art academies, particularly those in Paris. To foster similar opportunities in Canada, in 1872 the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA) was established by and for academically trained painters such as Hiester Reid to distinguish professionally qualified artists from their amateur counterparts. The OSA remains in operation to this day, making it Canada’s longest running professional art society. Following the goals set out in the OSA’s 1872 constitution, the society held annual art exhibitions to bolster a domestic market for sales as well as opening an art school and forming an art museum (now the Art Gallery of Ontario), both in Toronto.

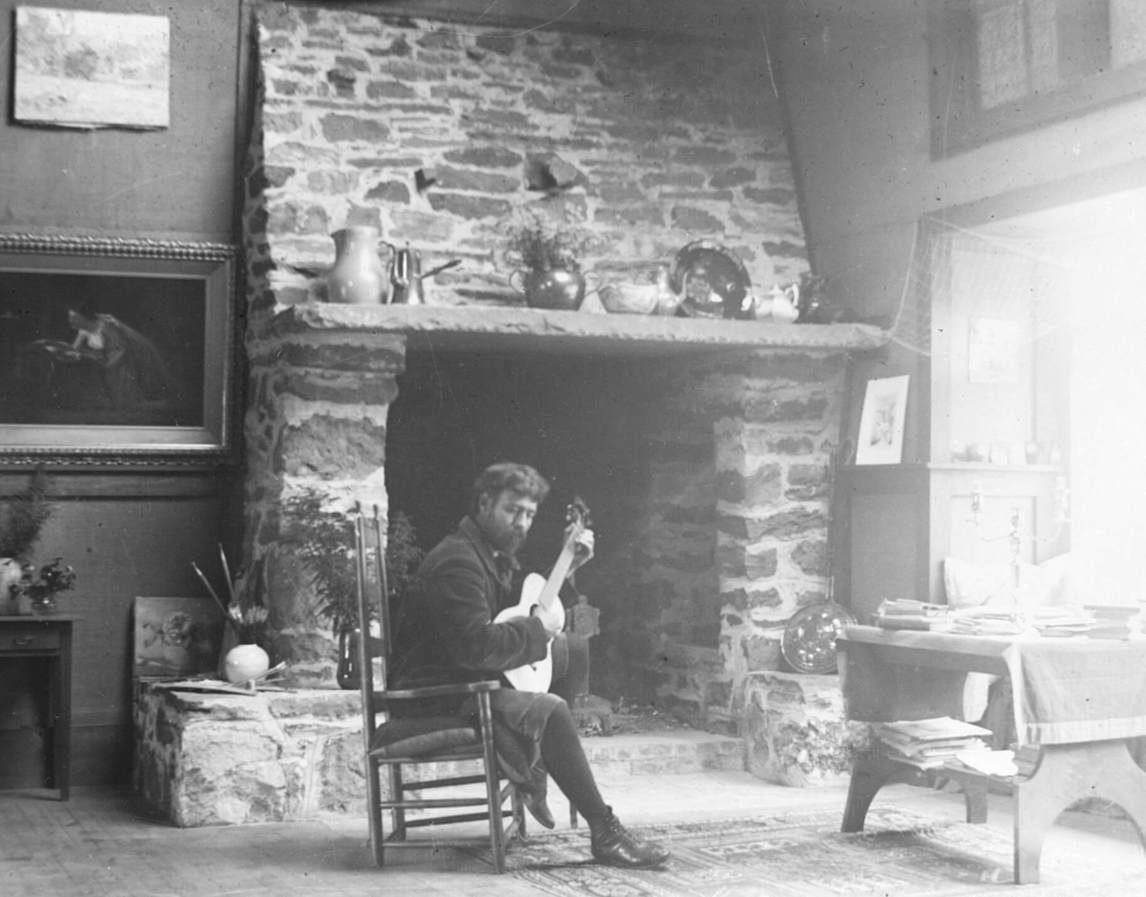

In 1876 the society opened Canada’s first professionally run art school in Toronto, the Ontario School of Art, now OCAD University. Society members taught all courses at the new art school, ensuring that students received standardized training on a par with that offered by European and American art academies. In 1887 both Hiester Reid and her spouse became members of the OSA; three years later George started teaching at the school. Earlier, however, he worked with Hiester Reid to distinguish their private teaching studio by creating a relaxed, inviting, and hospitable atmosphere. In his book Canadian Art: Its Origin and Development, art historian William Colgate (1882–1971) described the Reids’ newly opened teaching studio: “George A. Reid and his wife, Mary . . . kept open house for Toronto’s young art students; and by furnishing them with a room and a model kept the youthful artistic flame alive. In a social way also they offered a cordial welcome, with gracious and informal hospitality and relaxation, and also the valuable discipline which regular and supervised study enforced.”

Hiester Reid’s dedication to teaching reached across the border with the United States. In addition to teaching students in Canada, she and her spouse spent their summers from 1891 to 1916 teaching painting classes at the Onteora Club, a private literary and arts community in the Catskill Mountains near Tannersville, New York. The club was established in 1887 by Candace Wheeler (1827–1923) and her brother Francis Beatty Thurber (1842–1907), along with Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933) of the interior decorating firm Associated Artists. It offered Hiester Reid and Reid a house and studio so they could both teach and paint.

In the spring of 1895, arts columnist Lynn C. Doyle of Toronto’s Saturday Night magazine visited the Reids at Onteora, describing their efforts to set up “a summer school for painting.” According to Doyle, the Reids lived in a house surrounded by “some seven or eight acres,” and so George Reid “built a second house,” a studio space “where, during the last two summers, from four to six young women art students have done their own housekeeping in a light, summer fashion, in the intervals of painting, and have combined a most healthful summering with a good season’s work in art; painting sometimes with their teacher [sic], and at least always receiving a daily criticism.” Ultimately, the Onteora teaching studio accommodated ten students working simultaneously under the Reids’ guidance.

In her prolific teaching activities, Hiester Reid joined the ranks of artists such as Jeanne-Charlotte Allamand-Berczy (1760–1839), Louise-Amélie Panet (1789–1862), Eliza W. Thresher (1788–1865), and Maria Frances Ann Morris Miller (1813–1875), who had all “turned their creative abilities to financial account by giving art lessons.” Two of Hiester Reid’s more renowned students were artist Mary Riter Hamilton (1873–1954), known for her paintings of the aftermath of the First World War in Europe, and Hattie Blackstock (b.1894), an anatomy artist profiled in a 1929 Maclean’s magazine article, “Anatomical Art.” Cumulatively, these “brief references,” as art historian Janice Anderson writes, “create a picture of an artist who clearly worked as a teacher,” one who appears to have concentrated on working with women in particular.

To maintain her independent artistic practice, Mary Hiester Reid sold works such as Waiting by the Fireplace, 1889, and Playmates, 1890, in numerous venues. For example, she regularly submitted works to the annual juried exhibitions organized by the OSA and the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA), founded in 1880. Wealthy art patrons, collectors, and those employed by newly formed arts institutions such as the National Gallery of Canada (established in 1880), all attended these exhibitions, where they purchased artwork.

Hiester Reid also organized private viewings in the Reids’ studio, selling both her and George’s works to invited guests. They also sold works at auctions. In late May of 1888 they held a joint exhibition of their oil paintings, watercolours, and pen-and-ink sketches at the Toronto-based auction house Oliver, Coate & Co. At the conclusion of the exhibition, the works were then each sold to the highest bidder. George kept one of the sale catalogues, preserving it in his scrapbooks, which are now located in the Art Gallery of Ontario archives. The catalogue titled “Paintings by Mr. and Mrs. George Agnew Reid” lists the titles of the artworks but not who painted each one. George, however, jotted down the initials “M.H.R,” under thirteen of the ninety-three works listed, distinguishing for the record his wife’s art production and sales as separate from his own.

With this single auction, the couple raised enough money to finance their 1888–89 travels through Europe. Upon their return, Hiester Reid submitted “bright little picture[s]”—paintings of European scenes from her travels—to the annual exhibitions of the Ontario Society of Artists held in Toronto, as well as those of the Art Association of Montreal (AAM). In managing an active teaching schedule as well as a successful commercial art practice, Hiester Reid stimulated and maintained a high degree of commercial recognition for her work, something that art historian Kristina Huneault characterizes as “crucial for most professional female artists. . . . In establishing their careers women often had to negotiate places for themselves within predominantly masculine business communities.”

Though Hiester Reid painted mostly small-scale works, her husband gained acclaim for large-scale paintings that monumentalized the daily life of farmers and their families. Reid grew up working his father’s farm in Wingham, Ontario, and was able to draw on his understanding of rural life, as well as his academic training in life drawing and pictorial structure, to produce works such as Forbidden Fruit, 1889, and the much-lauded Mortgaging the Homestead, 1890. Mortgaging the Homestead depicts a father figure surrounded by his family who stands over a table and, in the presence of the seated lawyer, signs a set of mortgage papers in the hopes of saving the family farm. Measuring over 1 metre high and 2 metres wide, this work was first shown publicly in 1890 at the Royal Canadian Academy’s annual exhibition in Montreal. The RCA members so admired Mortgaging the Homestead that they elected George Reid a full member of the RCA. All newly minted RCA members were required to donate one of their works to the National Gallery of Canada to help grow its permanent collection. Reid gave Mortgaging the Homestead. Hiester Reid, however, was not granted associate member status until 1893.

Although artist societies and collectives like the RCA and the OSA initially accepted women into their ranks, they later adopted a more “businesslike” manner, putting in place discriminatory policies based on gender. Artist Charlotte Schreiber (1834–1922) achieved full RCA status when the academy was first founded in 1880. From that year on until 1913, “women artists were barred from full academician status and could only advance to the level of associate upon election by an exclusively male group of academicians.” As an associate member, Hiester Reid could neither hold a position on the executive council nor could she attend members’ meetings. It was believed that “a ‘lady’ should not know or concern herself with business and thus should not be involved in the running of these societies.”

Hiester Reid never became a full member of the RCA. Her husband, however, went on to be president of both the OSA (1897–1901) and the RCA (1906–7). (In 1913 the RCA removed the restrictions from its constitution barring women from joining the executive council and attending business meetings, but it was not until 1933 that the RCA elected artist Marion Long (1882–1970) to full membership status.) Mary Hiester Reid refused to allow these inequitable policies to impede her painting practice or her teaching career; she chose instead to steadfastly dedicate herself to the advancement of arts education for all in North America.

Critical Success

Over her lifetime Hiester Reid established a highly successful niche market for her work and distinguished herself as Canada’s pre-eminent painter of floral still lifes, with works such as Roses in a Vase, 1891. But the year 1892 proved to be a pivotal one in Hiester Reid’s critical success. That April the Art Association of Montreal presented her with a $100 award for the “best still life” for her work Roses and Still Life, painted c.1891. When she exhibited this same work two months later for the Ontario Society of Artists’ exhibition, the Toronto press praised it, with one reporter for The Weekly newspaper describing it as “more than an ordinary still life picture; it is poetry on canvas, and it is pleasing to know that the Montreal committee awarded it the prize when exhibited there. There are several other flower groups and still life studies in this exhibition, some of much merit, but the palm here must again be awarded to Mrs. Reid.”

The artist’s floral paintings not only demonstrated her mastery of a highly realistic painting style, they also garnered awards and acclaim. Public and private collectors actively began buying her floral still lifes. Most notably, in 1892 the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts purchased her work Chrysanthemums, 1891, for inclusion in the National Gallery of Canada collection. In 1893, and probably not by coincidence, Hiester Reid was accepted as an Associate Member of the Royal Canadian Academy.

In Hiester Reid’s day, flower painting was a genre considered to be particularly “suited to a female sensibility.” In her prolific output of flower paintings, Hiester Reid capitalized on social mores of the time, as well as on the larger and longer tradition of flower painting dating back over a century. Since the eighteenth century, European academies had trained artists based on a well-understood hierarchy of painting genres, with history located at the top, portraiture next, followed by landscape, and “at the lowest level still life.” Flower paintings were typically produced on small canvases, some as small as 23 by 30.5 centimetres. As the most highly valued and appreciated, history paintings generally appeared on large canvases to signal the monumentality of both the subject matter—the historic events depicted—and the artist’s skill. The size of canvases used for portraiture, landscape, and still life typically diminished according to their location in the hierarchy of painting genres.

The Antwerp-born artist Clara Peeters (c.1587–after 1636) and the Dutch artist Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750), however, challenged the supremacy of the academic system; both sold numerous stunning still-life paintings rife with flowers to wealthy Dutch and Flemish merchants. Rachel Ruysch ultimately became one of the most outstanding and highest-paid painters in all of Amsterdam. She studied botany as a young girl under her father, a professor of anatomy and botany, and she continued to paint after marrying and while raising ten children, working as an artist for nearly seventy years. On occasion, Ruysch’s highly realistic, scientifically informed and vibrantly coloured floral compositions even commanded higher prices than those by her male counterparts, such as Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669).

During Hiester Reid’s day some critics believed women might be more successful as artists if they stuck to the genre of still life and, in particular, flower painting. In 1898 one critic writing about Hiester Reid’s work referenced this belief, stating, “We wonder that so little attempt has ever been made to portray our native wild flowers [in Canada] in permanent fashion. There is room here for some artist—she must be a lady, of course, to make her name immortal in this line.”

In the early 1890s Hiester Reid’s work came to be highly sought after by burgeoning arts institutions and private collectors alike. Her paintings appealed to two overlapping yet distinct art economies: “fine art” and the commercial market. For example, the Art Gallery of Toronto’s 1888 purchase of Hiester Reid’s Daisies, produced that same year, marked the gallery’s first acquisition of several of her works. The gallery would later acquire through donation the paintings Chrysanthemums: A Japanese Arrangement, c.1895, and Castles in Spain, c.1896.

Sales of the artist’s work gained significant traction in 1892. In December Hiester Reid and her spouse held an exhibition of their work and then sold all the works at the Toronto-based auction house Oliver, Coate & Co. According to a journalist from Toronto’s Globe, it “attract[ed] great attention. Yesterday the building was crowded all afternoon, and from the business-like look in the eyes of the visitors, it was quite evident that they intend to be among the purchasers at the sale. . . . There are 191 pictures, so that all will have a fair opportunity of securing one.”

Hiester Reid’s artistic prestige and output seem to have increased significantly, evidenced by the fact that the 1892 sales catalogue (unlike the 1888 one) specifies which works Hiester Reid herself produced and which ones George Reid contributed. Asserting her position as an important and recognized contemporary artist, fifty-five of her works sold at the auction, including Chrysanthemums in a Qing Blue and White Vase, 1892. Hiester Reid’s paintings went on to be featured in solo exhibitions such as one held in November 1898 at the Matthews Brothers Gallery, located at 95 Yonge Street, Toronto. Saturday Night’s art critic Jean Grant reported that the exhibition featured a limited amount of works, “a holding back in the number of the paintings in order to admit a harmonious and restful effect,” the subjects being “flowers, landscapes and interiors.”

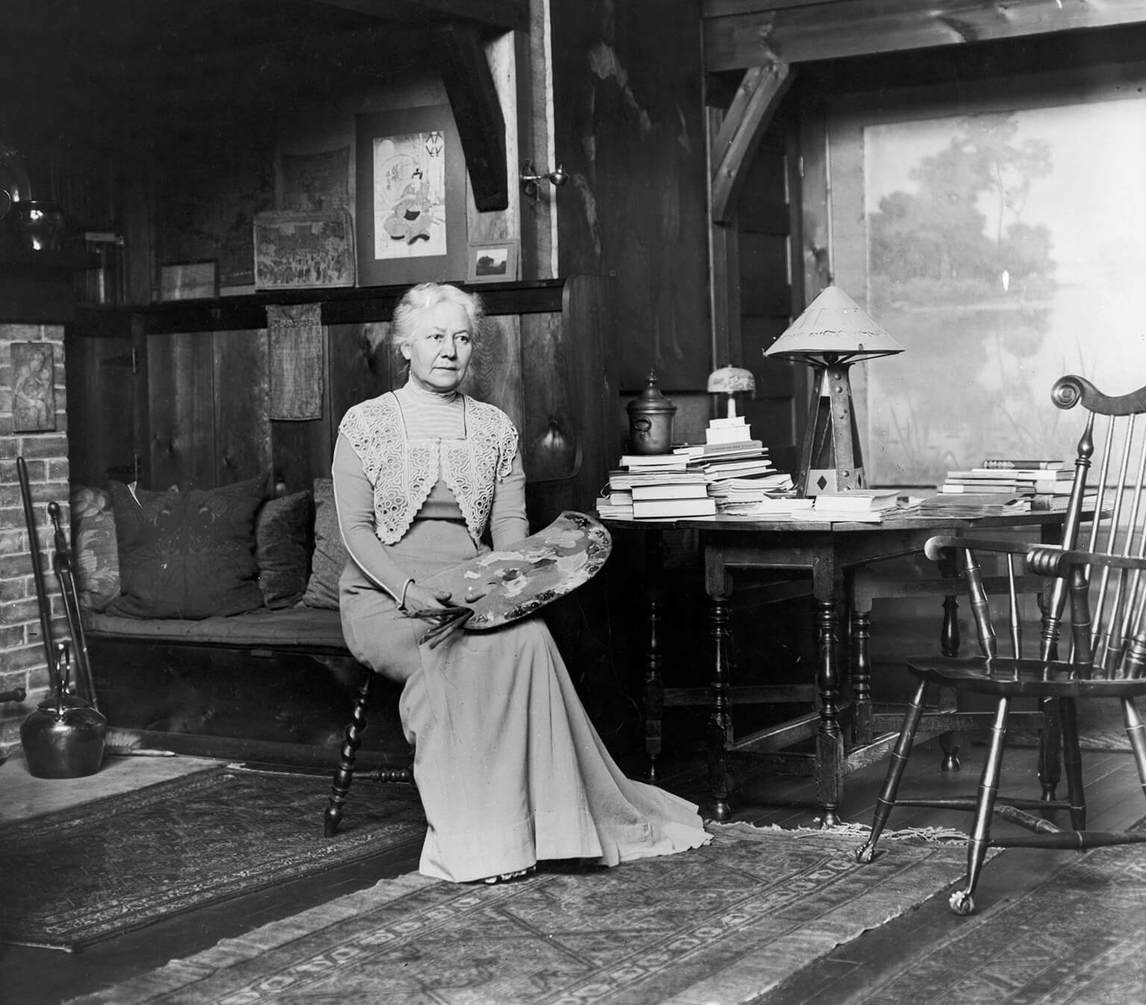

Though acclaim for her work was gaining momentum, Hiester Reid seems to have refrained from commenting to the press on her work to such an extent that Marjory MacMurchy, writing a profile on the artist for Toronto’s Globe newspaper in 1910, stated, “Nothing can tempt [Hiester Reid] to talk about her pictures.” One might suggest that her silence encouraged collectors, peers, and journalists to draw their own conclusions about her work. By 1910 Hiester Reid, along with her spouse, was a prominent figure in the Toronto art scene. While her husband gave numerous public lectures about his art, Hiester Reid may have recognized the less she said about her own work, the better. Certainly, the wealth of praise that Hiester Reid’s art received in the popular press over the course of her career and beyond demonstrates the merit of such an approach. In 1930 journalist M.O. Hammond (1876–1934) profiled Hiester Reid in his series, “Leading Canadian Artists,” again for Toronto’s Globe, describing her as one “who for years occupied a foremost place among Canadian women painters, . . . [and was] of a rare personality who, though almost shy, yet spoke eloquently by her work over a long period of years.”

Exploration and Collaboration

As her artistic career gained public prominence, Hiester Reid began to explore stylistic movements other than realism in her work. For instance, in and around the late 1890s she drew on the tenets of the Aesthetic movement, a British art and intellectual movement that emphasized the pursuit of beauty. A leading Aesthetic artist, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, liked to collect and display beautiful objects in his home to show their artistic merit. He also produced Tonalist art, a style distinguished by the use of soft, mostly dark colours. Whistler would often use musical terms in the titles of his Tonalist works to highlight the connection between an artist’s deployment of colour and tone and a composer’s arrangement of notes. One example is the title of his work Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, 1871, also called Portrait of the Artist’s Mother. Hiester Reid’s works such as A Harmony in Grey and Yellow, 1897, and At Twilight, Wychwood Park, 1911, showcase her engagement with the Aesthetic movement, one she embraced over the course of her career, as well as Tonalist art.

Hiester Reid also pushed her technical capabilities by looking to the works of French Impressionists, such as Berthe Morisot (1841–1895) and Claude Monet (1840–1926), whose work she encountered during her travels and studies in France. Using Impressionist strategies such as painting en plein air and loose brushwork to capture the effects of sunlight and shadow, she achieved adept results, as can be seen in Moonrise, 1898, and Looking East, 1899.

In 1908 Hiester Reid and George Agnew Reid made an important move to 81 Wychwood Park, where they would live for the rest of their married lives. Wychwood Park was first settled by landscape painter Marmaduke Matthews (1837–1913) in 1874. Afterwards the park grew to become a privately developed nine-hectare enclave located northwest of downtown Toronto. The Reids appeared to enjoy working together immensely, from co-managing a teaching studio to co-exhibiting their work. This dynamic and collaborative approach to artistic ventures was also maintained by a number of Hiester Reid’s peers such as Mary Bell Eastlake (1864–1951) with Charles Herbert Eastlake (1855–1927), Elizabeth Armstrong Forbes (1856–1912) with Stanhope Forbes (1857–1947), and Elizabeth Annie McGillivray Knowles (1866–1928) with Farquhar McGillivray Knowles (1859–1932).

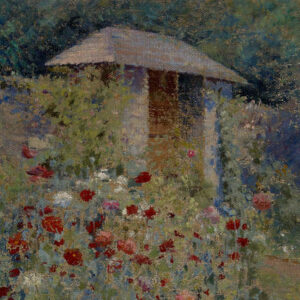

George, a former architectural apprentice, designed the house and incorporated the architecture of their Wychwood Park home into the surrounding landscape. Hiester Reid designed and maintained the house’s gardens, described in her day as “gorgeous tapestries drawn from nature’s bed.” Together they worked to make the house and the surrounding property a complete work of art, realizing the ambitions of the Arts and Crafts movement that had originated in Britain. During the 1850s, artists such as William Morris (1834–1896) and Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), took up the socialist philosophies of British art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900), calling for the elimination of the ideological divisions separating the fine arts and applied, or decorative, arts (or crafts) such as furniture design and production, as well as graphic design. Arts and Crafts reformers believed that the elimination of these divides within the arts would enable more people to be trained in craft production and empower them to leave factory work in polluted cities, which would in turn improve their quality of life and their aesthetic taste, as well as that of greater society.

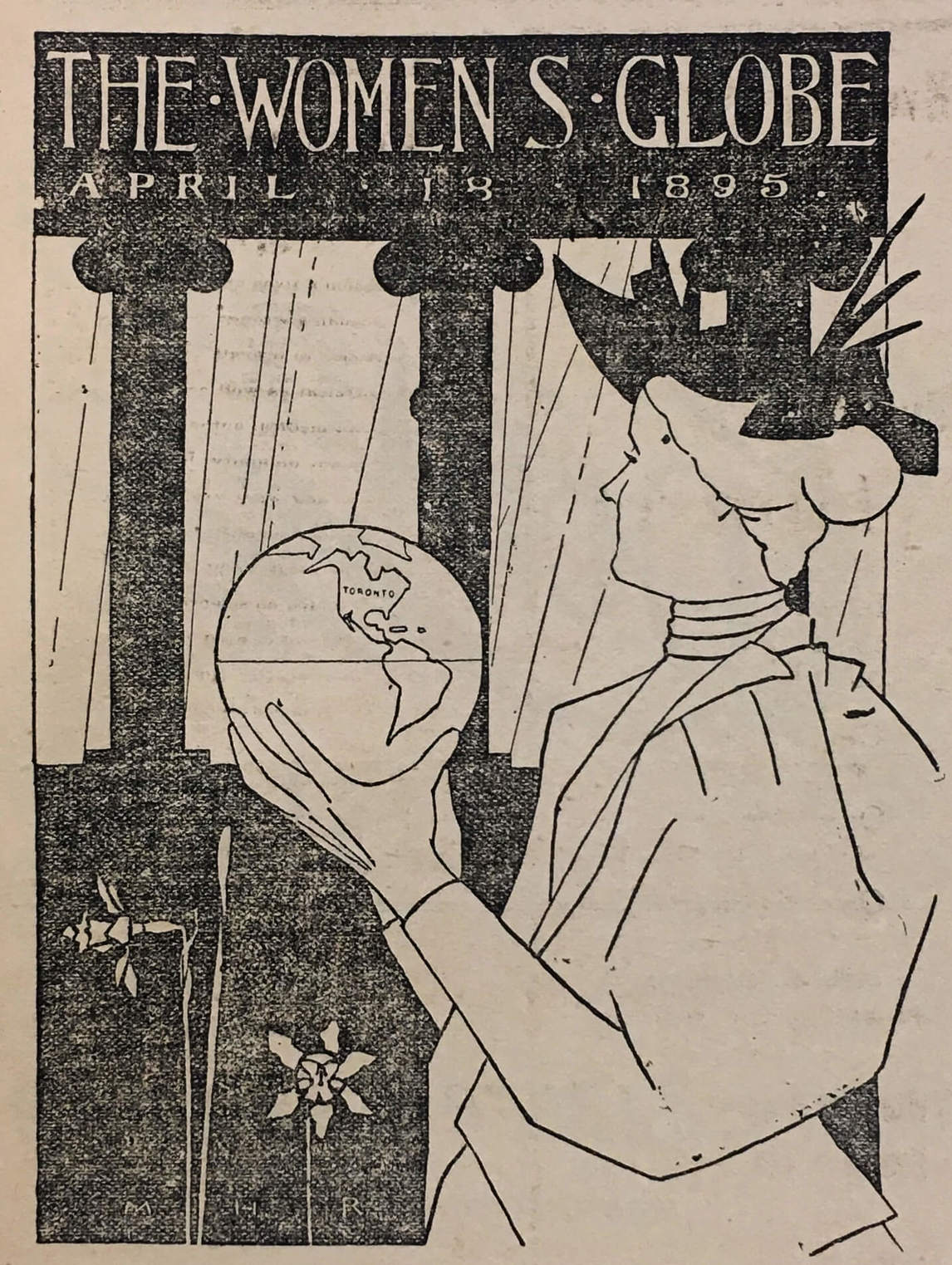

Morris’s writings were published in Canadian newspapers and periodicals, and undoubtedly Hiester Reid and her spouse read them. For her part, Hiester Reid took up the call of the Arts and Crafts movement to make art accessible to all through graphic design in her April 1895 colour poster for the Toronto newspaper supplement, Women’s Globe. The poster depicts a woman in profile holding a globe. Hiester Reid signed the poster as she frequently did her paintings, in the lower right corner with her initials “M.H.R.” Uniting high art training with applied art techniques, with this poster she created a work to be distributed to the Canadian public.

In 1902 Hiester Reid and Reid helped establish in Toronto the Arts and Crafts Society in Canada, which operated until 1910. They applied the society’s principles in the design and arrangement of their home, which they named Upland Cottage because it was located on the crest of a hill on their property. Characterized by one architectural historian as “elegantly simple,” the residence’s interior had a long and low horizontal layout, exposed timbers, and steeply sloping ceilings. George designed and built much of the furniture, and Mary painted a mural depicting a scene from their European travels, Castles in Spain, c.1896. The interior decor complemented the architectural design, merging high and applied arts. Unifying principles also determined the home’s exterior design, whose architecture blended in with the scenery in such a way that the residence and the foliage each complemented the other.

The Reids’ Wychwood Park home was not only a graceful expression of the couple’s collaborative life and dedication to the Arts and Crafts movement in Canada; it also reflected the ideas of the Aesthetic movement in the Reids’ efforts to accentuate the property’s beauty. Hiester Reid depicts the interior of her Wychwood Park home, styled according to her own aesthetic, in paintings such as Morning Sunshine, 1913, A Fireside, 1912—a work that depicts a fire-lit space defined by artfully arranged objects—and At Twilight, Wychwood Park, 1911, also an exploration in Tonalist art.

A Quiet Life

The years 1912 to 1919 were artistically quiet ones for Hiester Reid, though she was still involved in art teaching. In 1912 George Agnew Reid was appointed as the first principal of the newly formed Ontario College of Art in Toronto (now OCAD University), and Hiester Reid became a member of the college’s board. She worked actively to support its development by attending various school functions alongside her spouse.

Why there was a gradual decline in her artistic output after 1912 is not clearly understood. She may have built up a large enough patronage list and did not need to exhibit as regularly. Or she may have found herself more occupied with her work as a board member of the Ontario College of Art. Nonetheless, her established reputation meant that her work continued to show up in the press record. One instance of this occurred in the Toronto Star in 1917. In the wake of the First World War, women’s art came to dominate the annual exhibitions of the Ontario Society of Artists, the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, and the Art Association of Montreal, likely because so many men had left Canada to join the fight overseas. In response to this, the Toronto Star published an article provocatively titled, “They Do Not Merely Pose as Painters: Canadian Women Artists Have Done Distinguishing Work.”

Are there many women artists in Canada? What are they doing—what kind of pictures do they produce? . . . That they really work and don’t just pose as artists, that their studios are places in which to paint, not merely pour tea for admiring friends, is shown by the fact that at every exhibition their work appears and holds its own in comparison with anything in the exhibition. There may have been a time when painting was considered merely a ladylike accomplishment, but that time has passed.”

The article describes “the landscapes and flower studies of Mary H. Reid [in which] one always finds a poetical quality, a delicacy and beauty. Her garden scenes are always delightful.” Such an account signals what art historian Griselda Pollock refers to as the “inscription of the feminine.” As Pollock explains, women artists are designated as such to categorize their work as distinctly different from typical work by male artists, thereby entrenching the conceptual primacy of the male “artist-genius.”

A 1917 Toronto Star text characterizes Hiester Reid’s work as both “poetical” and “delightful,” this ultimately feminizes the artist’s work and distinguishes it from art produced by her male peers. More specifically, the account conflates Hiester Reid’s canvases with her character, which was commonplace in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century art writing and discourse. Analyzing an essay written by Charles William Jefferys (1869–1951) on Hiester Reid’s work, originally intended to be published as part of the catalogue for her 1922 retrospective exhibition at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario), Kristina Huneault explains that “women’s art was held to directly embody their female subjectivities.” But by developing her reputation as a flower painter, Hiester Reid styled herself as an artist mindful of social conventions and yet also accomplished, confident, prolific in her execution, and market-savvy. This stylistic approach ensured a successful practice during her lifetime—but it also led to her work fading into obscurity in the decades following her death in 1921.

Beginning in 1919 Hiester Reid suffered from angina; she died on October 4, 1921. After his wife’s death George Reid helped organize a memorial exhibition of her paintings that went on display from October 6 to 30, 1922, at the Art Gallery of Toronto. Featuring approximately 308 works, it was the first solo exhibition of works by a woman artist to be held at that institution since its founding in 1900. The next solo exhibition of a woman artist’s work would not be held until 1927, with the exhibition of Mary Bell Eastlake’s oils, watercolours, and pastels. The 1922 Hiester Reid exhibition showcased the diversity of her oeuvre. As Toronto-based journalist and arts commentator Hector Charlesworth noted in his review of the show, “One gets a sense of Mrs. Reid’s versatility,” with “the 76 paintings of flowers and still life; nearly thirty garden pieces; a dozen interiors; over one hundred landscapes; and many studio sketches of various subjects.”

Hiester Reid’s contemporaries contributed to the exhibition in various ways. Group of Seven founding member J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932) designed the In Memoriam MHR headpiece, published in the exhibition’s accompanying catalogue. The essay that illustrator, landscape painter, and muralist C.W. Jefferys wrote was titled “The Art of Mary Hiester Reid,” and Jefferys drafted it in straight-pen script. It was not included in the catalogue for unknown reasons. However, Jefferys’s admiration for Hiester Reid’s artwork came to light later when his essay was discovered in his archival papers, donated by the Jefferys Estate to the Edward P. Taylor Library & Archives at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, in 1989.

Jefferys’s essay was finally published in the catalogue for the 2000–1 exhibition Quiet Harmony: The Art of Mary Hiester Reid, co-curated by Janice Anderson and Brian Foss. The essay reads in part:

Canadian art, as we all realize, it still in its infancy; we are still on the frontier in this respect, and the number of its painters of distinction is as yet small; but . . . the name of Mrs. Reid will always have a prominent place. She is one of that little band of pioneers, akin to her sisters of the early days of settlement of our country, who brought back the rough places and the hard conditions of backwoods life, the graces, the gentle fortitude, and the inspiration that are woman’s peculiar contributions toward civilization.

In praising the “quiet strength and refinement” of Hiester Reid’s paintings, Jefferys implies that the artist’s life and work anticipate the Group of Seven, a collective officially formed in 1920, and whose ruggedly wild landscapes showcased the country as a natural resource ripe for further exploration and development. In contrast, Hiester Reid spoke eloquently to the sophisticated and moneyed tastes of the time by focusing on popular aesthetic elements. She produced canvases that celebrated cosmopolitan cultural sensibilities and achievements, leaving an oeuvre that documents a rigorous and lifelong pursuit of artistic study. Her work remains a vital contribution to the advancement and accomplishments of an active Canadian art scene in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements