Marion Nicoll is recognized as an influential educator and artist and for helping to usher Calgary’s art scene into modernity. Despite an uneven playing field for women, she became a painter of great national reputation, yet was only ever given the opportunity to teach design and crafts. She nevertheless found ways to integrate painting into her lessons and her mentorship of students was felt for at least three generations. Working virtually in isolation from others exploring experimental art forms, she remained committed to abstraction to earn recognition in Canada, Britain, and the United States.

Balancing “Fine Art” and “Craft”

When Marion Nicoll began her career, she inherited an art world in which there were rigid divisions between the so-called “fine arts” and the so-called “crafts.” Although today many contemporary artists are widely respected for their work with materials such as fabrics and clay, Nicoll faced a medium-driven art system—shaped by gender politics—where painting, sculpture, printmaking, and architecture were given privilege over all other media, including textiles, ceramics, beadwork, jewelry, and needlework.

Such hierarchies were clearly marked in Canada by official art institutions, most notably the first national art society—the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA). In their constitution of 1879, the arts were listed as including “Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Engraving and the Industrial Arts,” whereas work in other media was considered secondary, much of it designated to the expansive field of craft. The document explained, “No needlework, Artificial flowers, cut paper, shellwork, models in coloured wax, or any such performances shall be admitted into the exhibition of the Canadian Academy.” Underscoring these medium-based divisions was the fact that it was normally women who specialized in the excluded art forms, and they did not have the same access to the fine arts or professional paid employment that men did. Their work was automatically relegated to secondary status and they were expected to remain outside men’s arenas and not challenge the status quo.

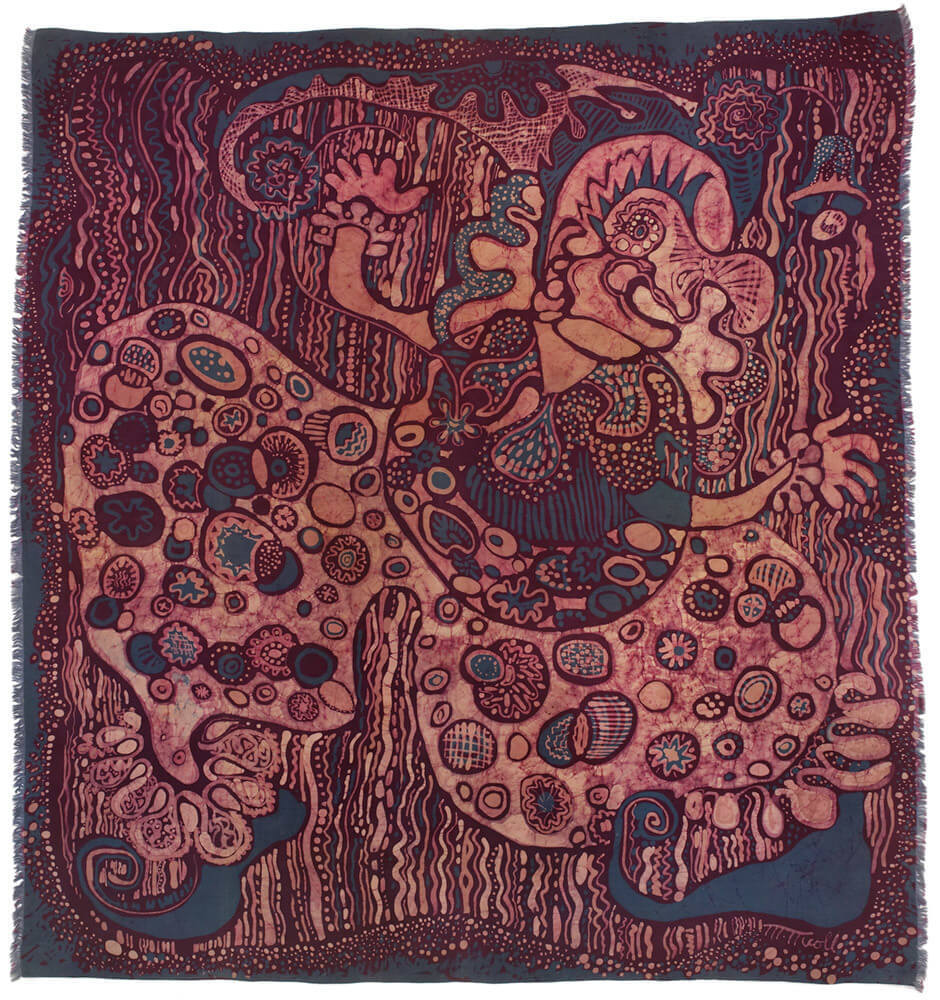

Nicoll’s education marked the beginning of her journey through these systemic challenges for female artists. At the Ontario College of Art, where she began studying under a cadre of male instructors in 1926, her courses included drawing, painting, and batik. By choice, her later program at the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art (PITA) focused on painting, the process in which she eventually established her legacy. But after graduation, Nicoll knew all too well that to be employed, as a woman, she needed a stronger education in crafts, and in 1937–38 she embarked on further study of textiles, weaving, bookbinding, mosaic, and pottery at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London, England. On her return to Calgary, she resumed working as an instructor at PITA, teaching fabric decoration and leather work, and after the Second World War, she became the head of the craft program. It was under her leadership that the college curriculum grew to national recognition. Henceforth she embarked on becoming a serious educator and practitioner, juggling both her painting and her work in fabrics, metals, and printmaking.

Nicoll went on to be an important spokesperson for the craft movement in Alberta and a leading figure in reviving the ancient batik art form of painting on wax. Not only did Nicoll take the craft profession seriously but she also challenged its gendered contours—she encouraged her male students to explore textiles. Her involvement as juror for the 1963 annual Albertacraft exhibition was a testament to her leadership in changing perceptions of craft to insist that it too was a legitimate art form. On the occasion of the 1965 Albertacraft exhibition, she boasted that, “The writer has seen many crafts shows on this continent and abroad and is able to say that this [is] one of the very best…there is none of the look of the local bazaar about it.”

For Nicoll, the craft field was not only a means to earn a living but also an arena she sought to expand and champion, and in which she aspired to establish new standards of excellence. From her earliest education to her last batik of 1967, she showed a sustained commitment to these goals. Her achievements in watercolour, oil, and drawing informed her textiles in a fluid creative process, and she considered all her work merit worthy. Her most important writings celebrated crafts—as she declared in one article, “The museums of the world are full of a wealth of this work.” In this regard, she was looked to by the government of Alberta, among others, as an expert in the field.

Teaching Legacy

From 1933 to 1965, Marion Nicoll was an instructor at the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art (PITA). She taught steadily, with the exceptions of 1937 and 1959, when she furthered her education in London and New York, and for six years after her marriage in 1940. For much of this time she was the only female artist on staff. In reference to her last years of teaching, when the college had 165 instructors, she said, “Don’t let them kid you that women are equal when it comes to jobs… When I left there, it took the time of a man and a half to do what I was doing.”

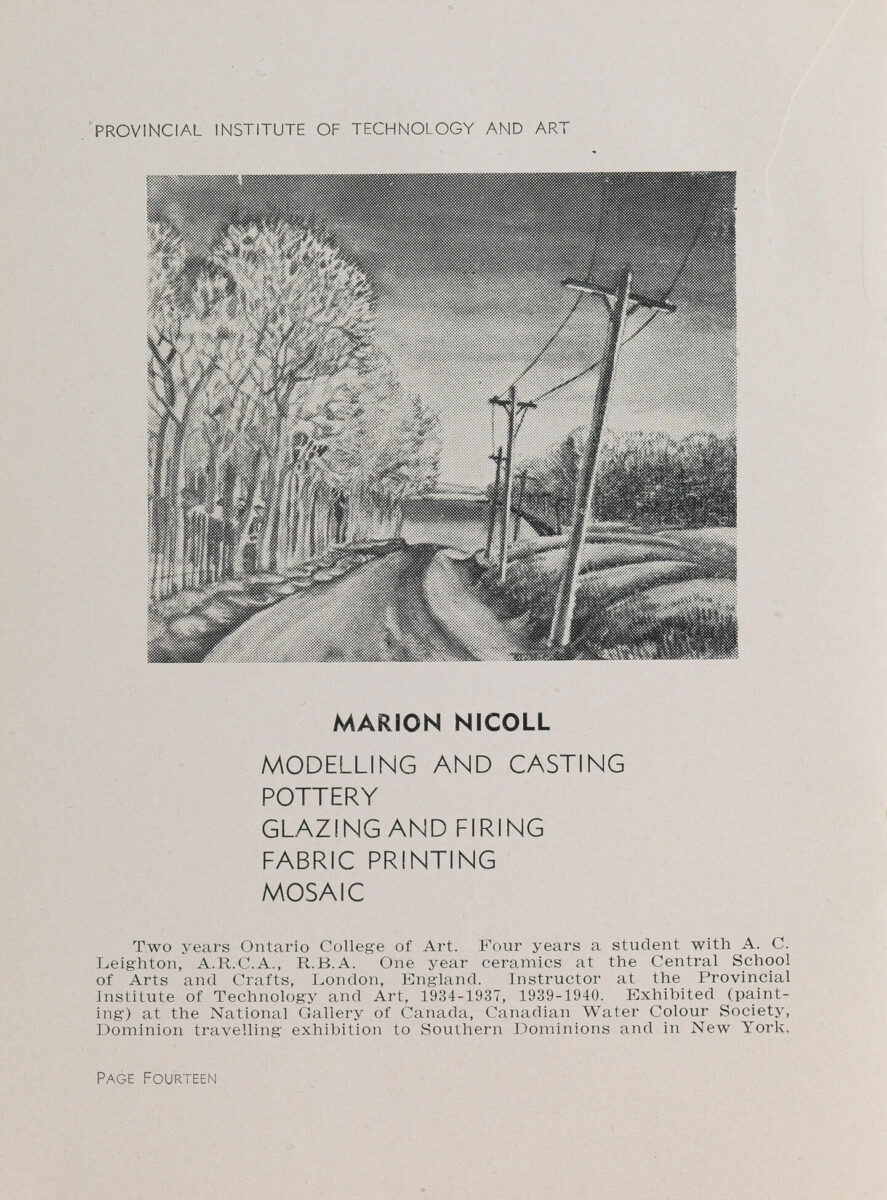

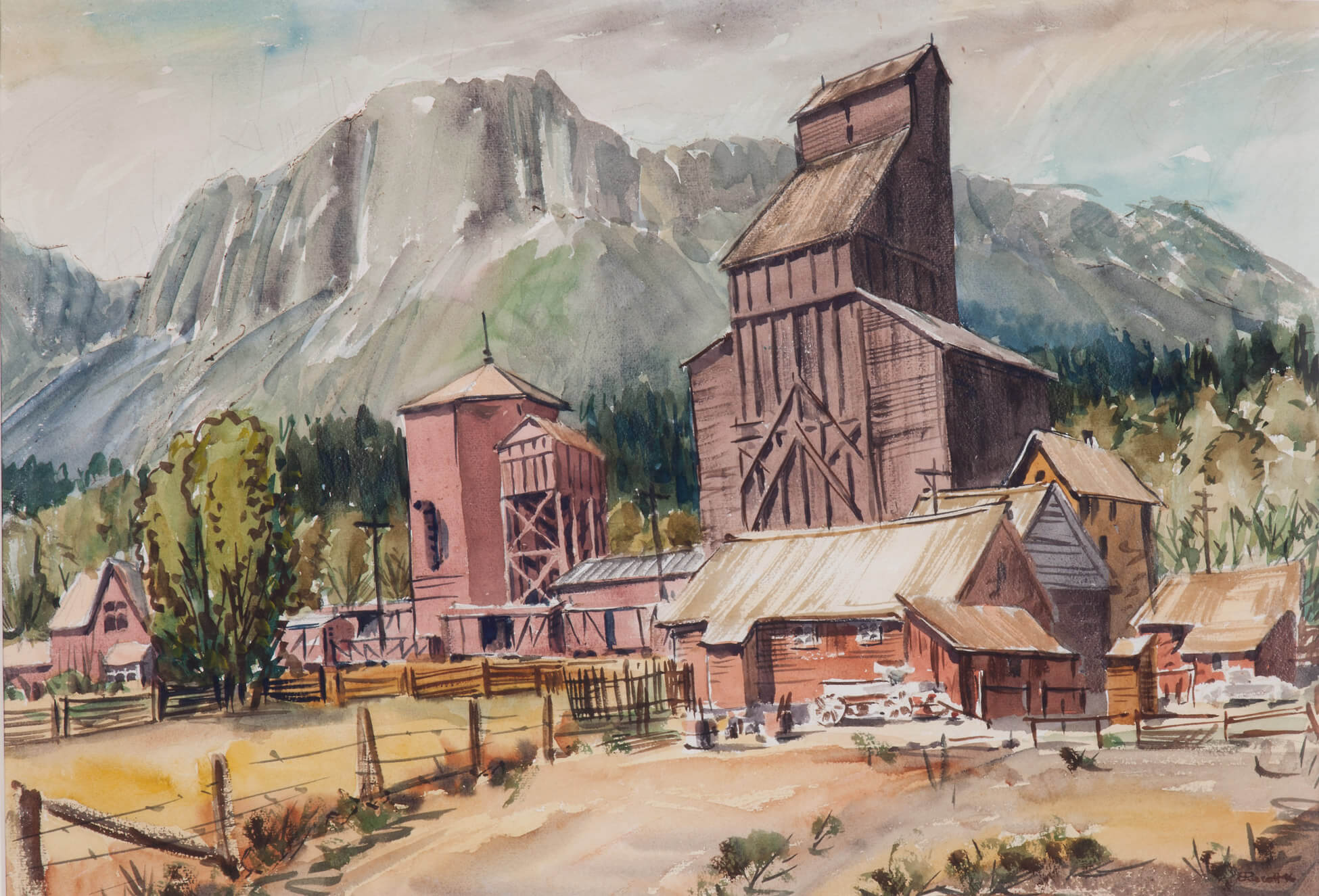

Nicoll’s role at PITA was to lead the School of Crafts, not the School of Painting, which was always given to men. Even so, she sustained a lifelong commitment to painting to become one of the most nationally recognized artists on staff. The 1947–48 syllabus identified James Dichmont (1875–1962) and James Stanford Perrott (1917–2001) as instructors in Drawing and Painting. Nicoll was named instructor for Ceramics, yet her instructor profile illustrated one of her landscape paintings in watercolour.

It surely irked Nicoll that Perrott was given that role when he had been one of her former students; like her, he was experimenting with landscape in the late 1940s. After she passed away in 1985, Perrott credited Nicoll as “the rock upon which everybody stood when they were starting out to make art.” As PITA grew after 1948, a lineage of male instructors in the School of Painting followed, including Henry G. Glyde (1906–1998), Walter Phillips (1884–1963), Illingworth Kerr (1905–1989), and Ron Spickett (1926–2018). Despite the inequalities towards women, Nicoll persisted, developing an impressive teaching legacy and list of accomplished graduates while challenging gender norms and balancing her own success.

Nicoll was committed to establishing a strong foundation for her students in a wide variety of materials and media and a thorough understanding of the formal elements of art. Her Design and Handcrafts course included working with batik, printing in silk-screen, block relief and stencil, tie-dye, jewelry, and leather, and emphasized skill development, with attention to rhythm, balance, opposition, harmony, line, tone, and texture. Her lectures on colour stressed the study of both its history and psychological effects. She insisted that her students be well versed in the theories of Albert H. Munsell (1858–1918), who advocated an understanding of the roles of hue (colour), value (lightness or darkness of colour), and chroma (the strength or weakness of colour).

Teaching was primarily a vehicle to support Nicoll’s artistic practice and for her to earn a living. Nonetheless, she took her pedagogical responsibilities seriously and remained steadfast in her belief that “Nobody can teach you to be an artist. Absolutely nobody. All this business of teaching techniques is bass-ackwards [sic], because a technique is a ‘result’ not a start.” When once asked what makes a great teacher, she replied, “It is the ability to inspire their students.” Nicoll felt that the most important support she could give was to foster self-expression. She had learned from working in automatism that a way to find that voice was to turn to the inner self, and she encouraged her pupils to do the same.

As a teacher, Nicoll is remembered as a compelling force who “suffered no loafers or prima donnas in her classes.” As students George Mihalcheon (1924–2011) and George Wood (b.1932) reminisced, “She scared the hell out of everybody.” ManWoman (1938–2012), who took her batik courses, considered her his favourite teacher. “She gave me a strong sense of design…. She helped me discover my own originality and belief in myself…I remained very close to Marion and had a special relationship with her.” Ceramics student Luke Lindoe (1913–2000) attributed the foundation of the Ceramics program and its growth to Nicoll.

John K. Esler (1933–2001) found her to be “the most impressive of all the staff. She was a strong force…at a time when women could hardly get jobs in that area. Her strength of character and determination for excellence made her a very powerful person in Calgary and Alberta.” Perrott remarked, “It was her subjective example and her interest in people that made the difference. She started me out when I was floundering and put the joy of art into my head and into my heart. In the world of art, which can be so mechanical and material, her values were aristocratic and civilized.”

Confronting Discrimination

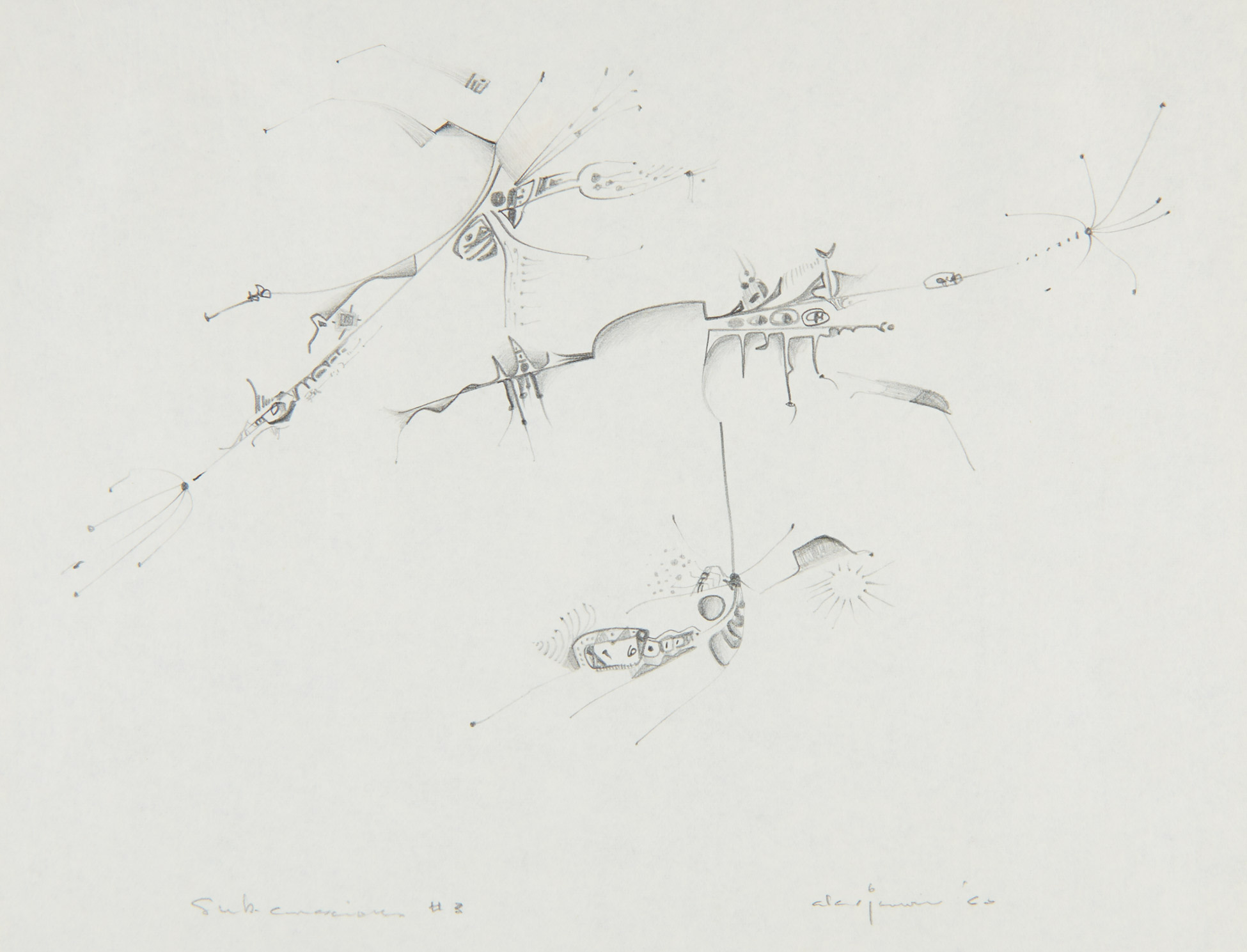

Having faced professional sexism in her own career, Nicoll was supportive of others who were facing systemic barriers, including on the basis of race. She championed Dene artist Alex Janvier (b.1935) when he was experiencing racism from the Department of Indian Affairs, who tried to force him to take commercial rather than fine art and threatened to withdraw his financial support. Nicoll joined him to fight the department to a standstill until he was allowed to study painting. Janvier’s Subconscious Series, 1960, was among the results of her teachings in automatism and he has subsequently been recognized for his lyrical abstractions and images of residential school history.

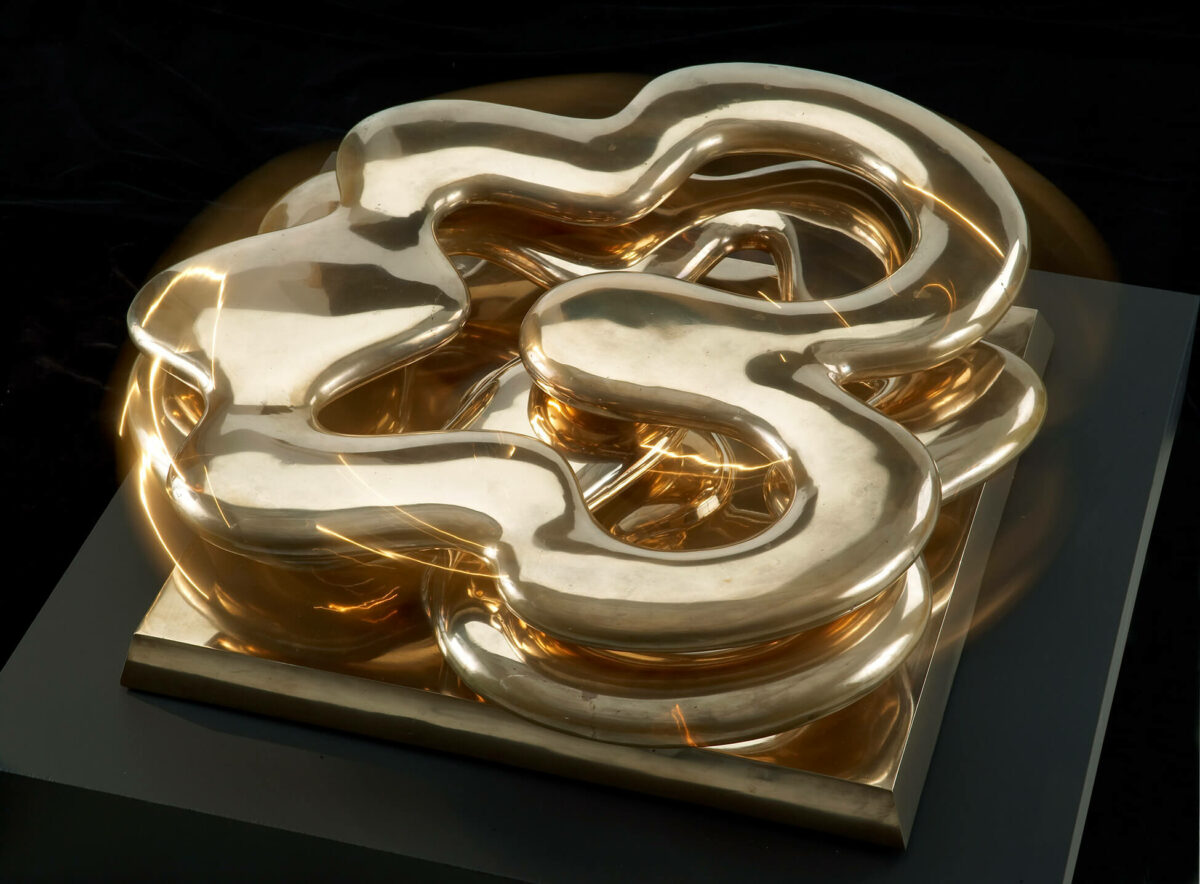

Nicoll was well known for challenging gender norms. Painter Carroll Taylor-Lindoe (formerly Moppett) (b.1948) recalled, “No one really knows what she had to do to maintain her position. There are an awful lot of women my age and older who are glad she was there. Many of us thought Calgary wasn’t quite the right place for her, but we are indebted to her for staying here.” Nicoll also encouraged her male students to create fabric art—a field traditionally associated with women—and Derek Whyte later led a crafts program for the New Brunswick government. Sculptor Katie Ohe (b.1937)—whose biomorphic sculptures, such as Puddle I, 1976, are in effect kinetic automatics—has said definitively that “Marion Nicoll is at the root of everything art is today in Calgary.”

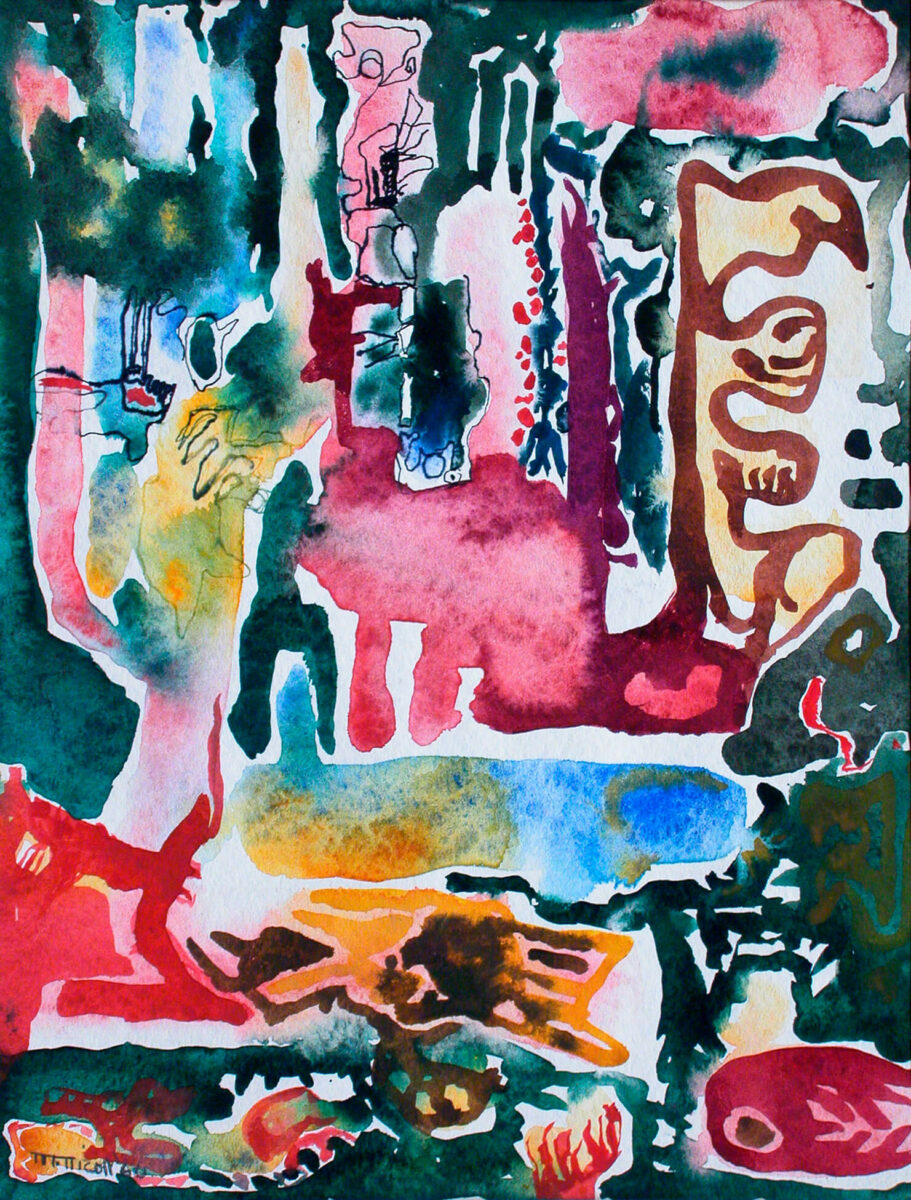

Nicoll found alternate means to teach painting and abstract art forms regardless of her official circumstances as lead in the School of Ceramics. Her Finger Painting course taught the Chinese method from the Tang dynasty, which she explained “instilled rhythm and freehand expression” and the results, she conceded, “are of course abstractions.” So too her courses on string cylinder printing and metal and wire construction realized abstractions. In 1963, Jenni Morton’s article “Painter Teaches Craft Classes” offered a public platform where Nicoll made it known that she “would have preferred to teach painting rather than crafts.” Another opportunity soon followed to discuss her “success elsewhere, but not in Calgary” and, when she stated that “all I ask of life is to paint,” she hinted that her patience with teaching was finite. She was working on large series of paintings, as can be seen in Ritual I, 1962, and Ritual II, 1963.

On December 30, 1965, Nicoll tendered her resignation. She said, “Teaching didn’t bother me at all. What bothered me was the garbage around it. The bells, the reports, the chain of authority, discipline.” To the college vice-principal, she announced that it was either retirement or she would remain on sick leave. Only then did she learn how much her colleagues valued her. Principal Illingworth Kerr replied, “I believe that an art school has not a constant quality but has at any time no more than the sum total of its instructors and their ability to share experience, so we cannot admit that ‘any one is expendable.’ Your individual quality as an instructor cannot be replaced.”

By January 1966, with her teaching career completed, she was finally able to make art her full-time priority. The Marion Nicoll Gallery at what has now become the Alberta University of the Arts was later named in her honour to recognize her outstanding teaching career, and it is known for presenting exhibitions of student work.

Strengthening Community

The modern evolution of Calgary’s art community was enriched through Nicoll’s art, memberships, public service, and the opening of her Bowness home to visitors. In addition to her memberships with the Calgary Sketch Club and Alberta Society of Artists, she joined informal collectives, including the feminist Women Sketch Hunters of Alberta and the Calgary Group, which was committed to modern expression. She was also a notable voice of support for work in craft and design, participating in the establishment of arts infrastructure, public demonstrations, exhibition adjudication, volunteer committee work, writing, and exhibiting.

With Calgary Alderman Mary Dover in 1958, Nicoll assisted in forming the Log Cabin on St. George’s Island, Bow River, one of the first local outlets for the sale of quality handmade crafts. Her public interviews documented the processes of batik fabrication, ceramics, and silk-screen printing and she spoke proudly about the successful batik work of her students. Her publication Batik (1953) was one of four brochures issued by the Alberta government’s Cultural Activities Branch. In her essay “Crafts in the Community,” she stressed design excellence and a desire to nurture the artist’s “feeling of kinship with the craftsman of the past and others working all over the world.” Among her goals was the desire that “the crafts produced in this province will bear the unmistakable stamp of this country and its people.”

As a volunteer, Nicoll offered service to organizations in Calgary, Edmonton, and Montreal. In Calgary, she acted as organizer, chair, and juror for the annual exhibition series Albertacraft. The 1963 exhibition included entries from across Canada and her juror’s statement noted that “the use of materials …is showing more imagination… and the quality of work rising steadily.” Nicoll also served as judge for the Alberta Government’s scholarship awards, member of the Alberta Visual Arts Board, and advisor for the Canadian Handicrafts Guild.

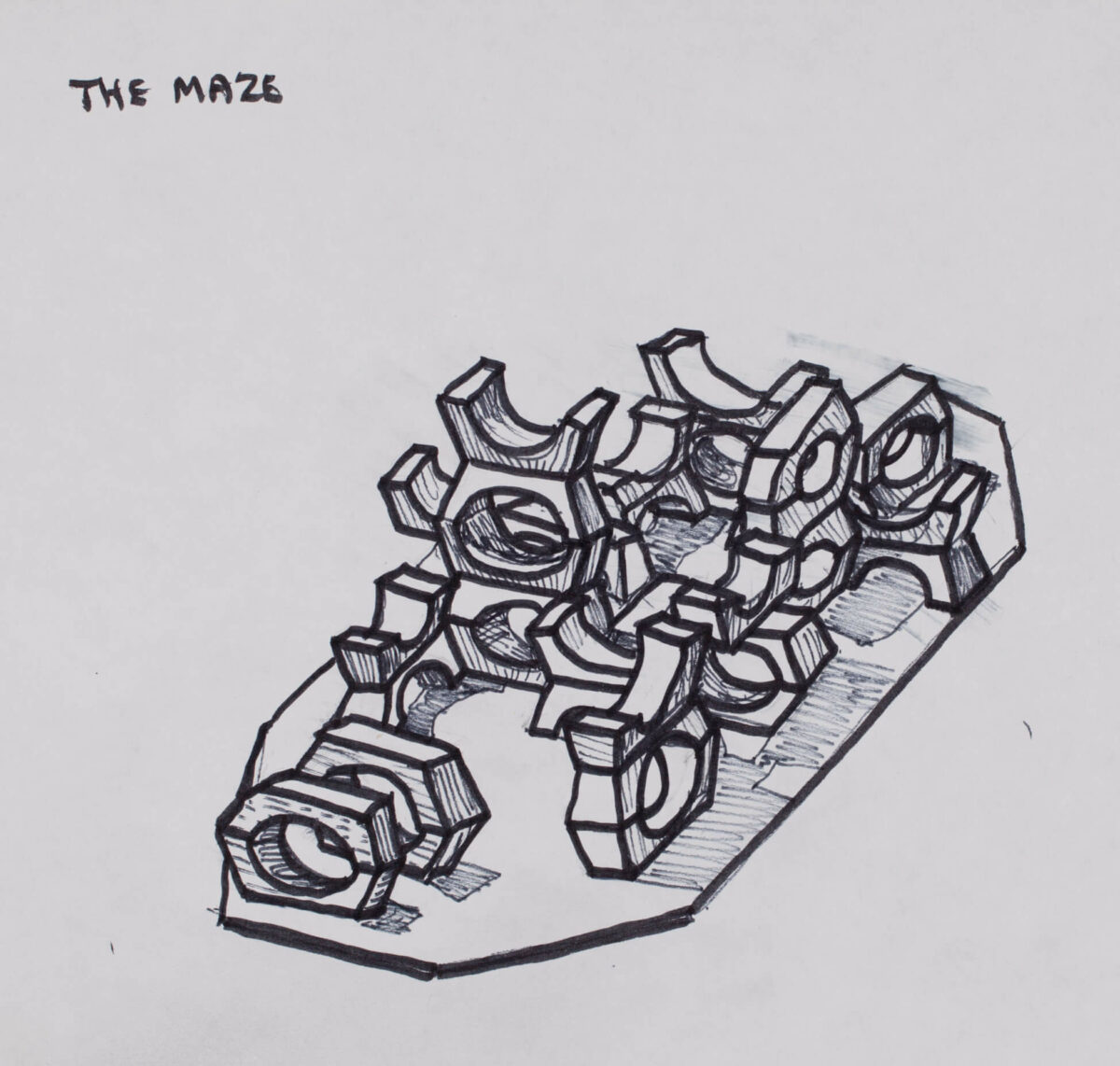

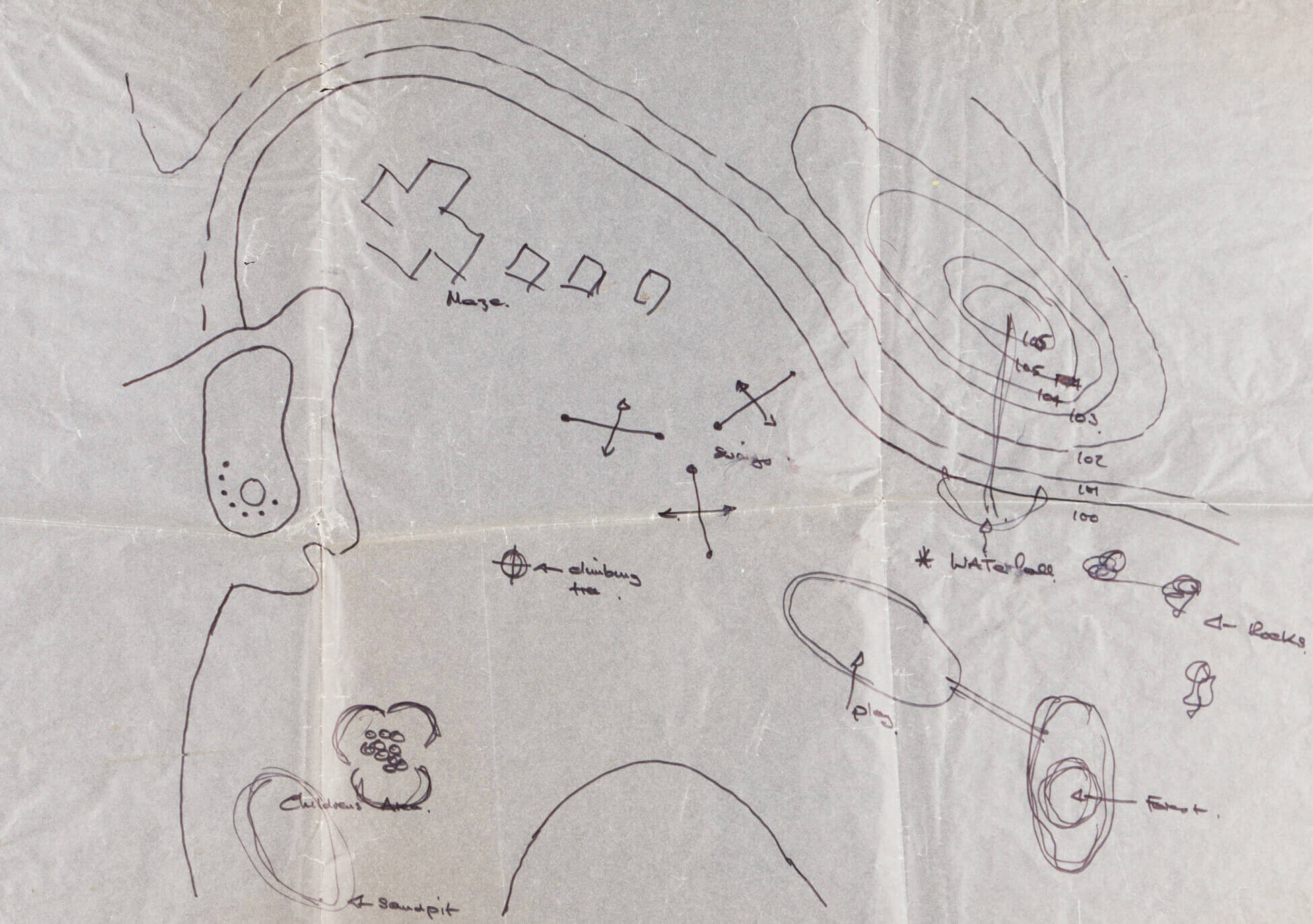

Nicoll envisioned that the artist also had a vital role in public planning, including urban environments. For Environment ’69, an interdisciplinary group exhibition of artists and architects succeeding the former Albertacraft, she developed a concept vision for a children’s playground that included a maze, moveable wall unit, people wall, climbing and sliding unit, combined swing and climbing bar, and natural rock area. Her aims were threefold: make a fun place for children that stimulates their natural desire for play, adventure, innovation, and fantasy; create a focal point that enhances the neighbourhood at any time of the day or year; and finally, integrate the environment into the natural landscape so that it emphasizes the unique character of the country. Some elements of this proposal were later realized for the Bowness Montgomery Day Care Association, Calgary, but those elements have not survived today. Her plans show how she transformed her experiences in abstraction from two to three dimensions: she took a geometric approach for The Maze, a space for children to climb and crawl, and an interplay of organic forms for the Natural Rock Area.

For several decades, the Nicolls opened their Bowness home to welcome visitors and encourage conversations about art. This generosity of community spirit led to many fond memories. Lifelong friend Janet Mitchell (1912–1998) remembered how often the artist couple entertained and held summer garden parties, saying, “Long after her students left the college they would find their way out to the Nicolls’ for advice, a letter of recommendation, or simply for absorbing conversation… Even their friends were extraordinary. Their friends were, and still are, from every kind and condition and position. If one has a guest from out of town, one invariably took them to the Nicolls’; and it generally was a visit long remembered.”

Abstractionist in Isolation

From her earliest landscapes to her final abstractions, Nicoll’s painting practice was ongoing and, by the later 1950s, it became her driving force, the medium through which she most wanted recognition. “No man in his right mind would become a painter by choice to-day. A painter is one because he must be,” she observed. “I wouldn’t be anything else.”

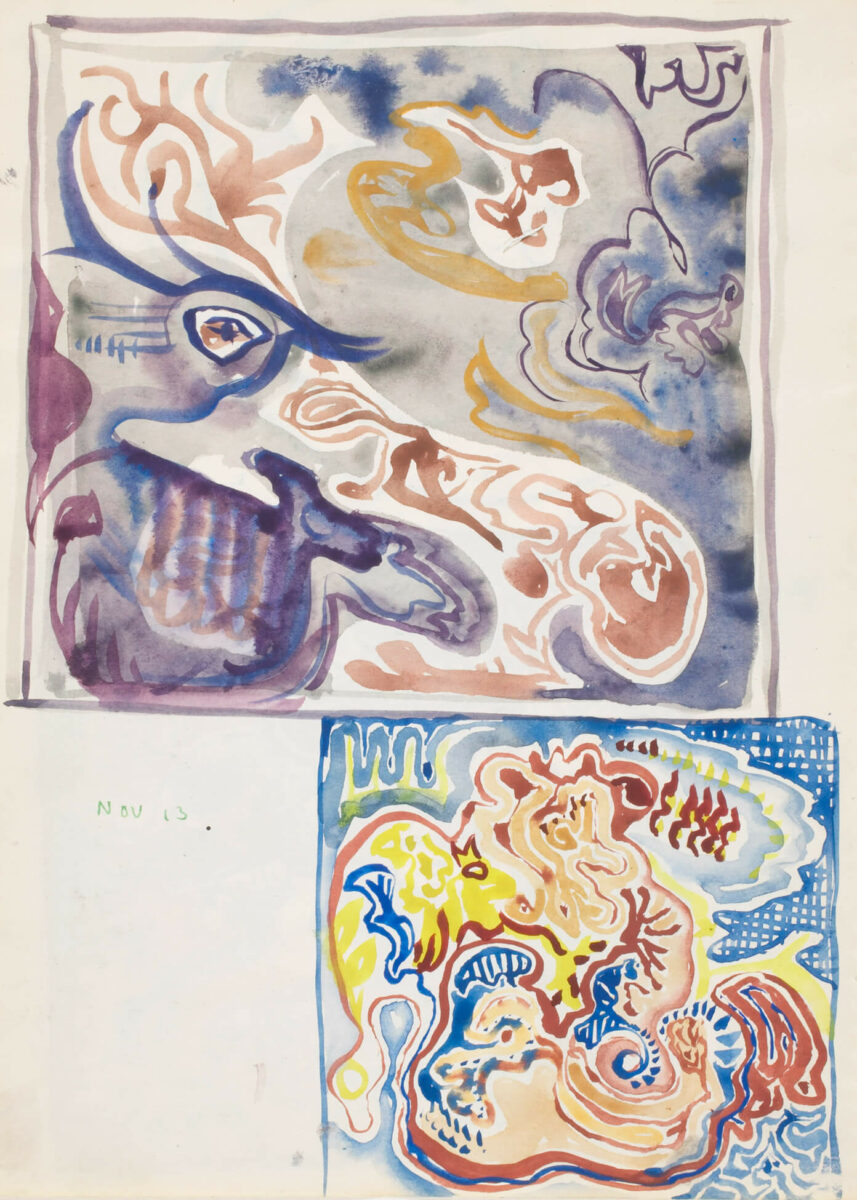

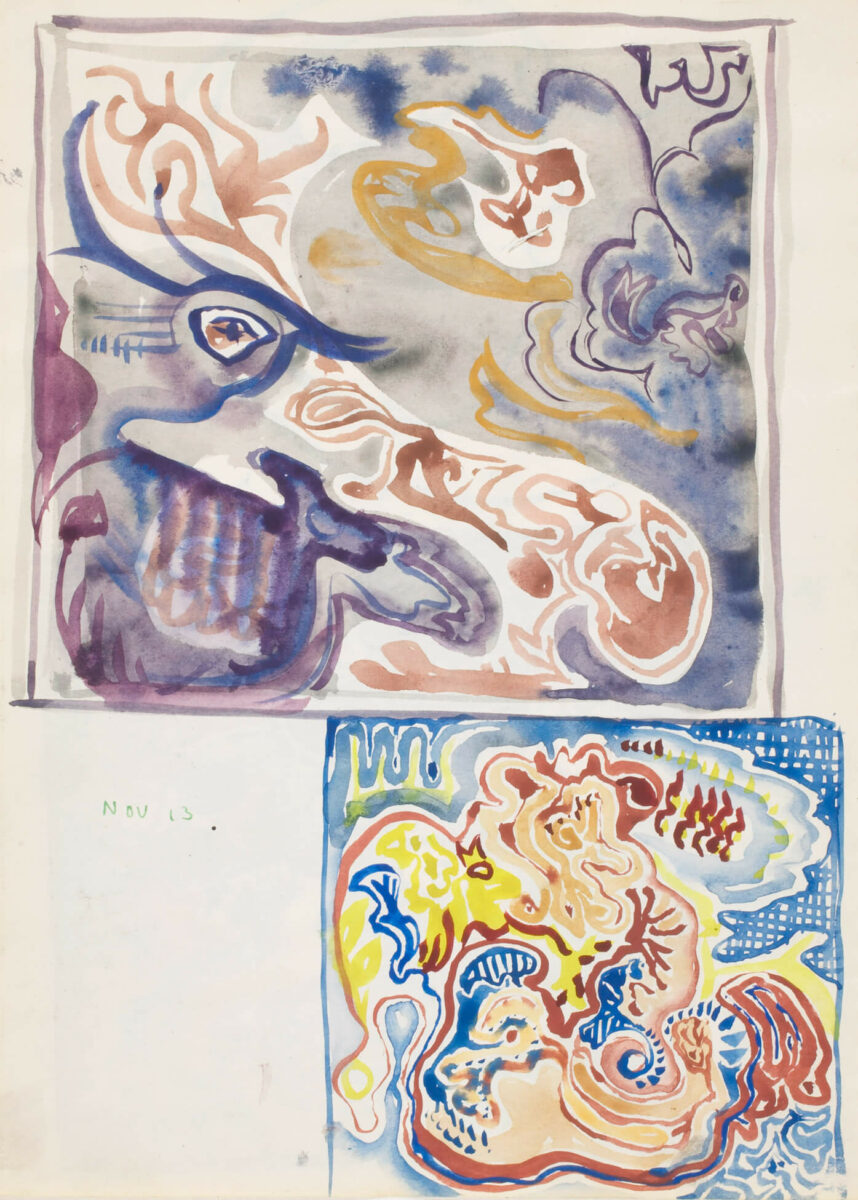

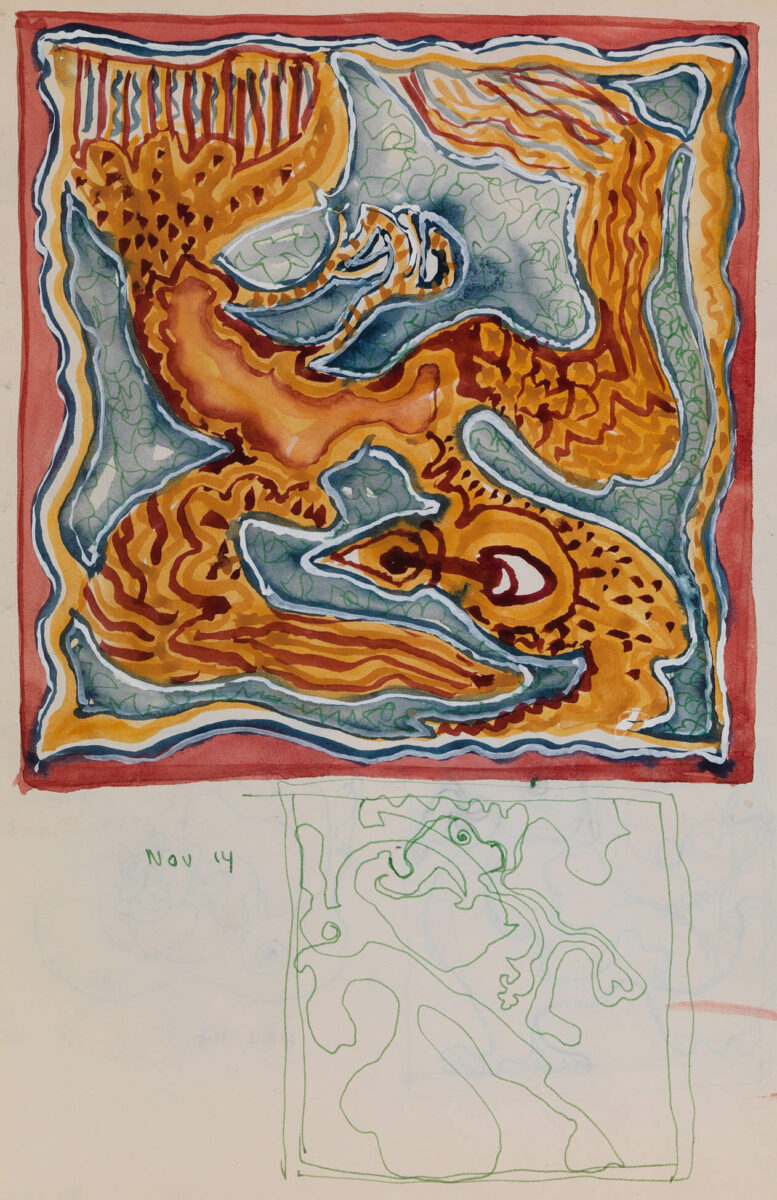

Considering the geography in which Nicoll worked, it was an astonishing accomplishment that she sustained her practice in automatism. After Jock Macdonald’s (1897– 1960) departure for Toronto in 1947 she remained alone in Alberta in her pursuit of this method, experimenting in works like those known as Untitled (Automatic Drawing), 1948. She was far removed from the European Surrealists who produced automatic drawings, such as Francis Picabia (1879–1953), Jean Arp (1886–1966), Salvador Dalí (1904–1989), André Masson (1896–1987), Max Ernst (1891–1976), and Grace Pailthorpe (1883–1971). These artists used methods such as frottage (rubbing), doodling, collage, and collaboration, and their efforts measurably expanded the possibilities of drawing. As Leslie Jones, associate curator of prints and drawings at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, has observed, the Surrealists fostered a process of “freedom, the ability to try new things at a moment’s notice, allow oneself to slip up, make mistakes, take a different path.” Nicoll likewise appreciated that “you can’t make a mistake in automatic drawing.”

Nicoll looked to established artists including Russians Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) and Marc Chagall (1887–1985), whom she considered among the first automatic abstractionists. She read articles about her peers in Canadian Art magazine, which featured Automatiste and Surrealist artists from Montreal including Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960), Jean Paul Riopelle (1923–2002), Marcelle Ferron (1924–2001), and Jean-Philippe Dallaire (1916–1965). She was familiar with the Automatiste manifesto Refus global (1948) and probably took note of the group’s inclusion of women—Madeleine Arbour (b.1923), Muriel Guilbault (1922–1952), Thérèse Renaud (later Thérèse Leduc) (1927–2005), Françoise Riopelle (1927–2022), Françoise Sullivan (b.1923), and Ferron among them. Nicoll also read Vie des Arts to compare her work with the Montreal art scene. She kept on hand British psychologist P.W. Martin’s Experiment in Depth (1955), which she considered a valuable tool for self-analysis, for he encouraged the recording of one’s dreams from the subconscious.

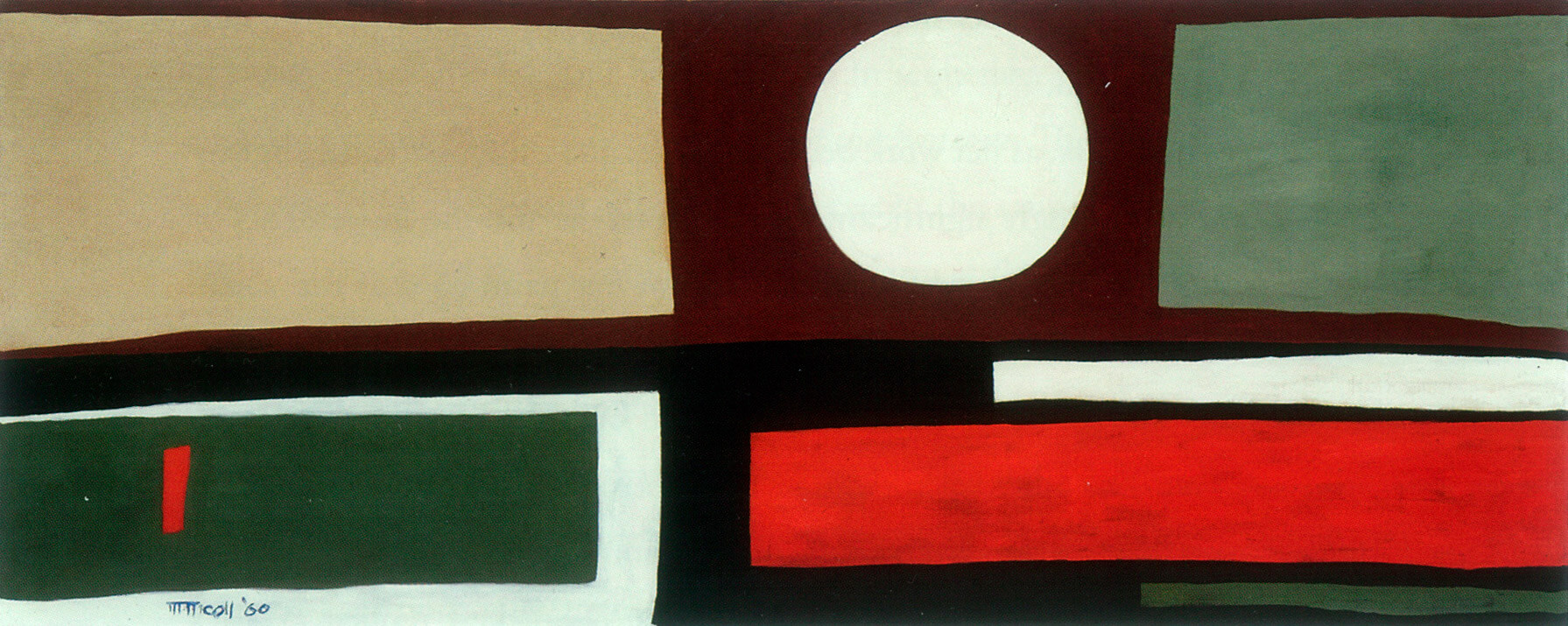

Through her automatics, Nicoll had sharpened her two-step process of accessing the subconscious to create images. When she turned to hard-edge painting in 1959, creating works such as Thursday’s Model, 1959, and Alberta Vl, Prairie, 1960, she added a third step—observe the external world; turn inwards to distill, sort, and order what she had seen; and finally, capture these images in paint. Martin’s Experiment in Depth was surely welcome reinforcement of Nicoll’s capacity to engage in the process of moving back and forth between inner and outer worlds through the process of what he named withdraw and return—what she lived as an abstract artist. Nicoll explained what it was to be in steps two and three of her process as follows: “When I’m painting, I bring my whole critical faculty to bear…. You’re constantly accepting, rejecting as you paint…afterwards then you bring your real critical faculty and decide…whether it is right or wrong.…You use the whole person you can’t just be all intuition any more than you can be all mental.”

Automatism, through which Nicoll had learned the process of her inner reality, her ability to withdraw from the outer world and return afterwards as exhibiting artist, remained with her. She never released her paintings from the actual world to be only about pure form and colour because her environment continued to matter to her. Abstraction was her vocabulary because it synchronized with her lived time—modernity.

As Ann Davis, former director of the Nickle Arts Museum at the University of Calgary, has argued, Nicoll’s abstractions were also deeply spiritual compositions expressed through silence and alchemy. As she explains, alchemy is a philosophy based on the transformation of matter and abstraction is a way to articulate the spiritual. It is to convert the physical to the metaphysical, and to allow the inner world to be visible. Building on Kandinsky’s idea of total realism (transmutation of the worldly object) and total abstraction (silence about the world), the artist reduces the artistic to a minimum and “art no longer represents but presents.”

When Nicoll made the decision to shift to hard-edge abstraction, she continued to work in isolation, and that problem was exacerbated in Calgary after she moved back from her year spent living in New York. Gender continued to be a social obstacle to inclusion within the hard-edge painting movement. She was geographically far from Les Plasticiens, Quebec’s hard-edge painting movement, in which there were no female artists. She participated in the National Gallery of Canada Biennial Exhibitions of Canadian Painting in 1963, 1965, and 1968, and, while finally on the national stage, she was in all three instances the only female artist from Alberta. Overall representation of women in these exhibitions only ranged between 10 and 12 per cent of the total exhibitors.

Joyce Wieland (1930–1998), who was then an emerging Canadian feminist artist, was also included in the 1965 biennial. Wieland and Nicoll had coincidentally both made the transition to abstraction in 1959, but they are not known to have met one another. By 1968, when William Chapin Seitz (1914–1974) declared hard-edge abstraction “an essential style, if not the style of our age,” Nicoll may no longer have been alone in the genre, but she remained one of its few female practitioners in Alberta. She exhibited with Chicago’s Vincent Price Gallery in 1968 but otherwise never re-entered the American hard-edge scene after New York.

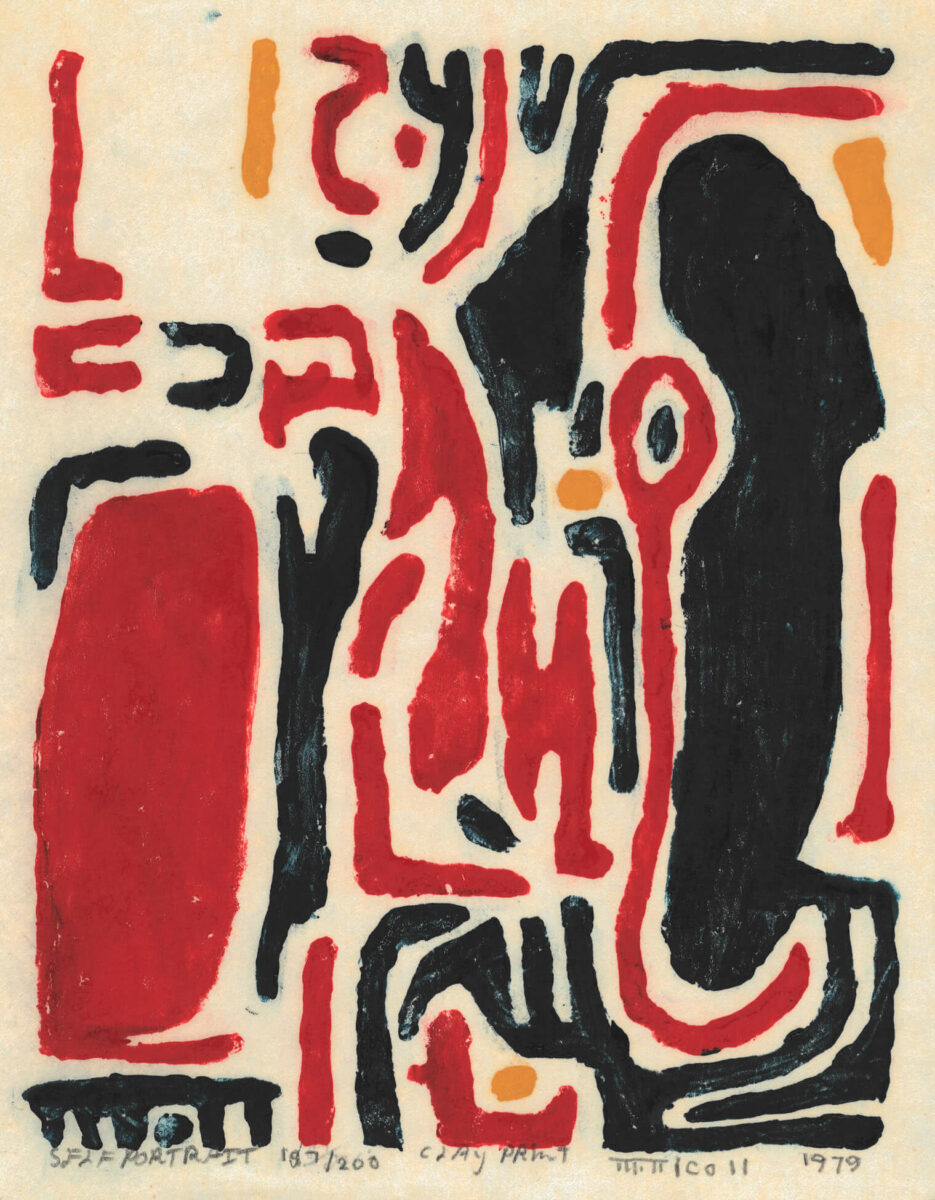

Nicoll envisioned her hard-edge painting practice to be her most important artistic legacy and that it was cut short at age sixty-three from arthritis was regrettable. After 1971, she drew and made prints when she could cope with her physical discomfort. Among her last known works of art was the print Self Portrait, 1979, made to accompany the first monograph on her life and art, Marion Nicoll: R.C.A. Like many of her prints, the image was an extension of her painting practice—this one following the oil painting Self Portrait, which she created in New York in 1959. It was no coincidence that she chose to bookend her practice with these two images to close two decades of her feminist journey. When she painted the 1959 Self Portrait in the hard-edge genre, she consciously marked the self as her centre. That year also marked the year she became a public abstractionist in her first solo exhibition. For the balance of her life, it was her hard-edge painting that brought her recognition and the way she wanted to be remembered.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements