Watkins’s life and work are significant in different ways. She was trained in a school that emphasized the uses of art as well as teaching photography as art. It also explicitly promoted women in the profession of photography, providing space for a New Woman to become independent and contribute to public life. As a student and a teacher in that school, influencing a new generation of American photographers, Watkins was instrumental in the development of American modern photography. In the new world of commodities and magazine advertising, she was at the vanguard of advertising photography. Her success was built on her original way of seeing and photographing everyday life in the home. Although she was lost to history for almost fifty years, Watkins is now recognized in Canada and internationally as a pioneering modernist photographer.

Clarence H. White School of Photography

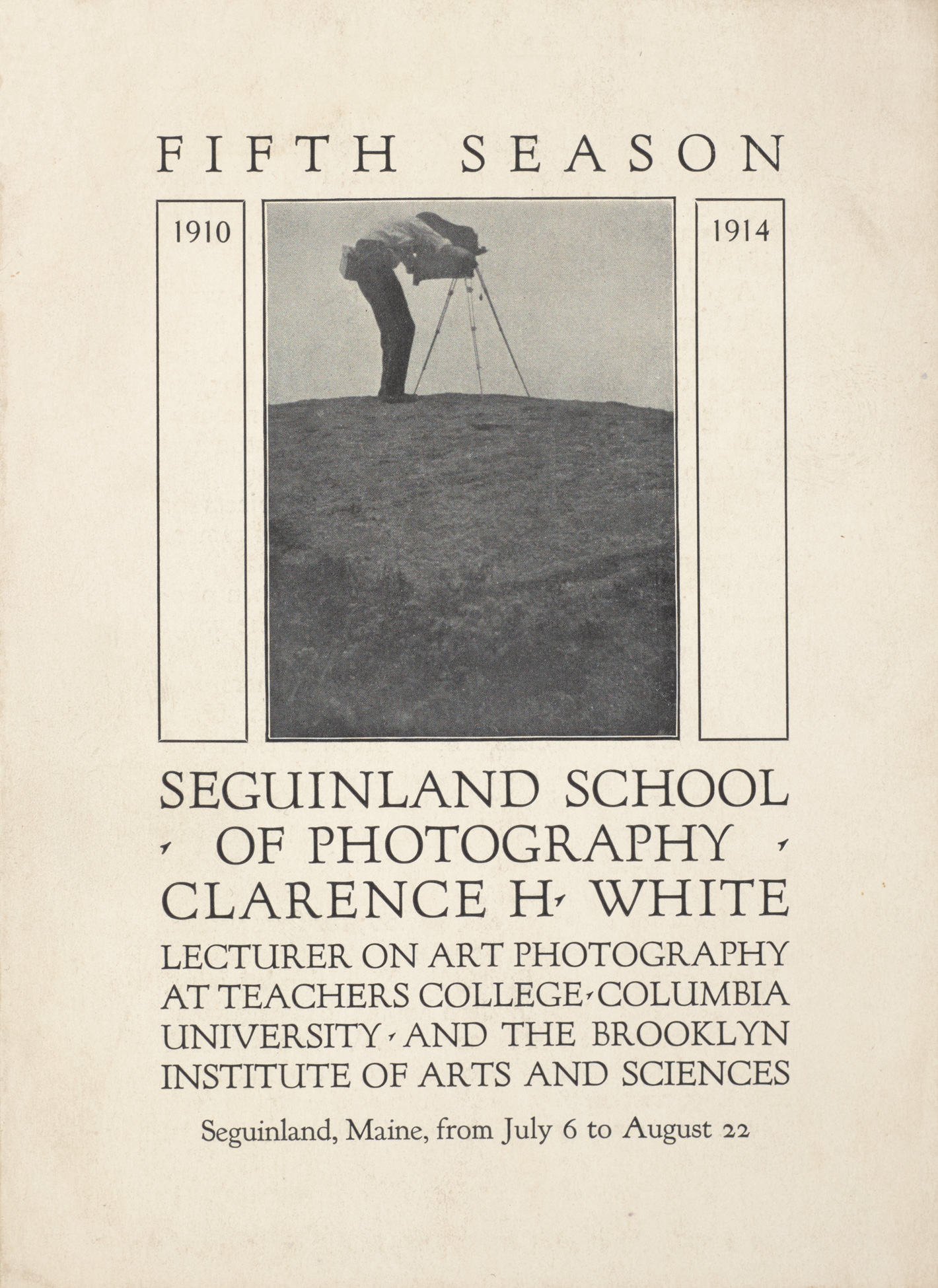

Although Margaret Watkins began working as an assistant to Arthur L. Jamieson in Boston in 1913, it was her summer course with Clarence H. White (1871–1925) in Maine the following year that shaped her art and began her career. She noted in her agenda, “wonderful time & much inspiration.”

The Clarence H. White school, the first in America to teach photography as an art form, announced itself as an institution that taught the uses, or “vocation,” of the medium. It offered guidance in the production of artful photographs, but it also advised on professions in photography, whether studio portraiture or, eventually, advertising. In 1919, White hired Frederic Goudy (1865–1947) to teach a course that focused on the photograph in print and advertising photography. White’s socialist inclinations, his desire to use art to help the world, and his visionary teaching were an important gift to those who, without family wealth, wanted to combine their love of art with an income. The Arts and Crafts ethos of the school found no conflict between art and commercial work: practitioners believed in the value of beautiful objects and that the commercial world and artistic one should work together. The school also welcomed and respected women, for whom photography had become a possible profession. Watkins was one student who benefited from this ethos and education.

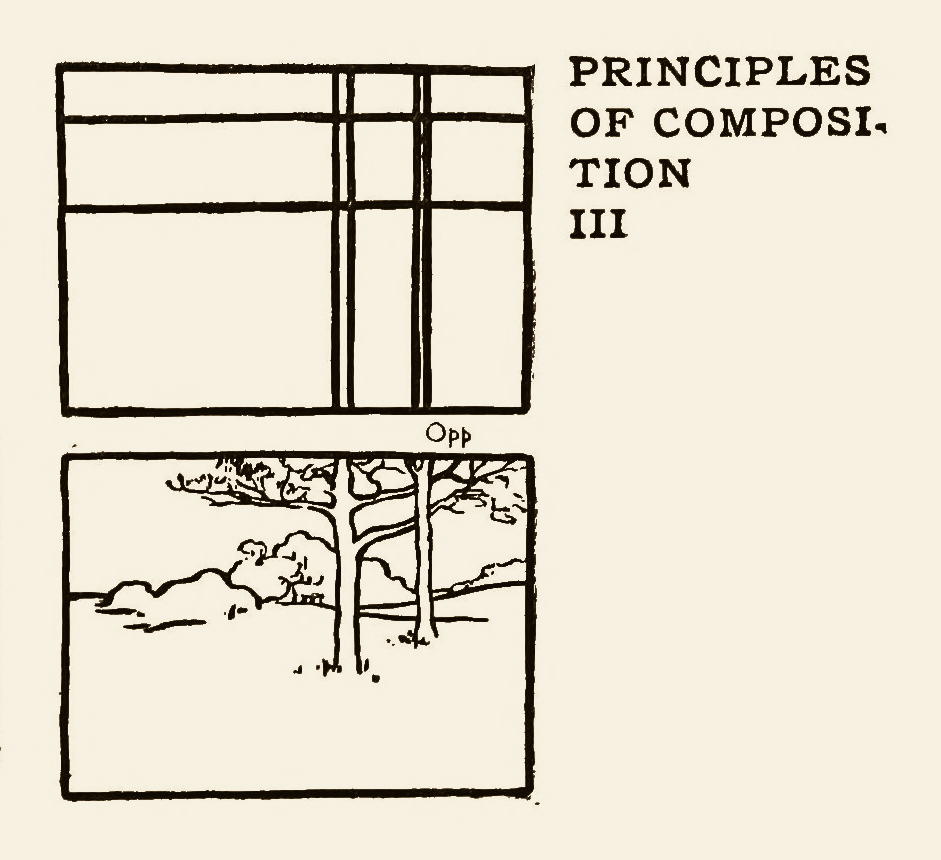

White was known as a notable Pictorialist photographer, and in 1902 he had co-founded, with Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946), the Photo-Secession movement, which promoted photography as a fine art. As an educator, White was influenced by the teaching methods he learned from Arthur Wesley Dow (1857–1922), whose book Composition discussed the design elements of line, mass, and space that applied to all forms. White also adopted a teaching approach proposed by philosopher and educational reformer John Dewey. His “project method” encouraged students to develop critical thinking and problem solving through experimentation. White would set problems of design, exploring curves, angles, line, or tone, but to be solved in the students’ own environment—the students thus discovering their own expression.

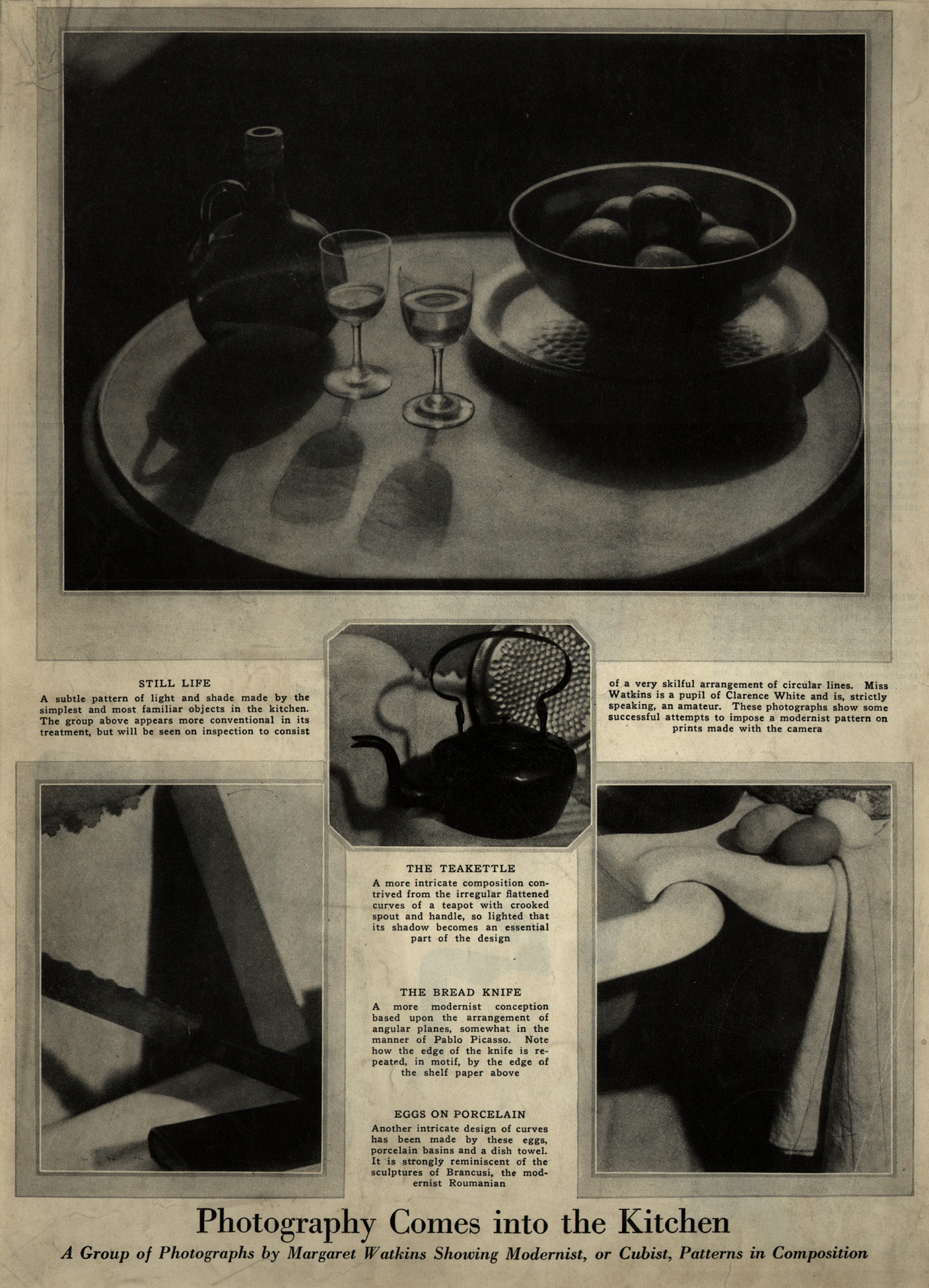

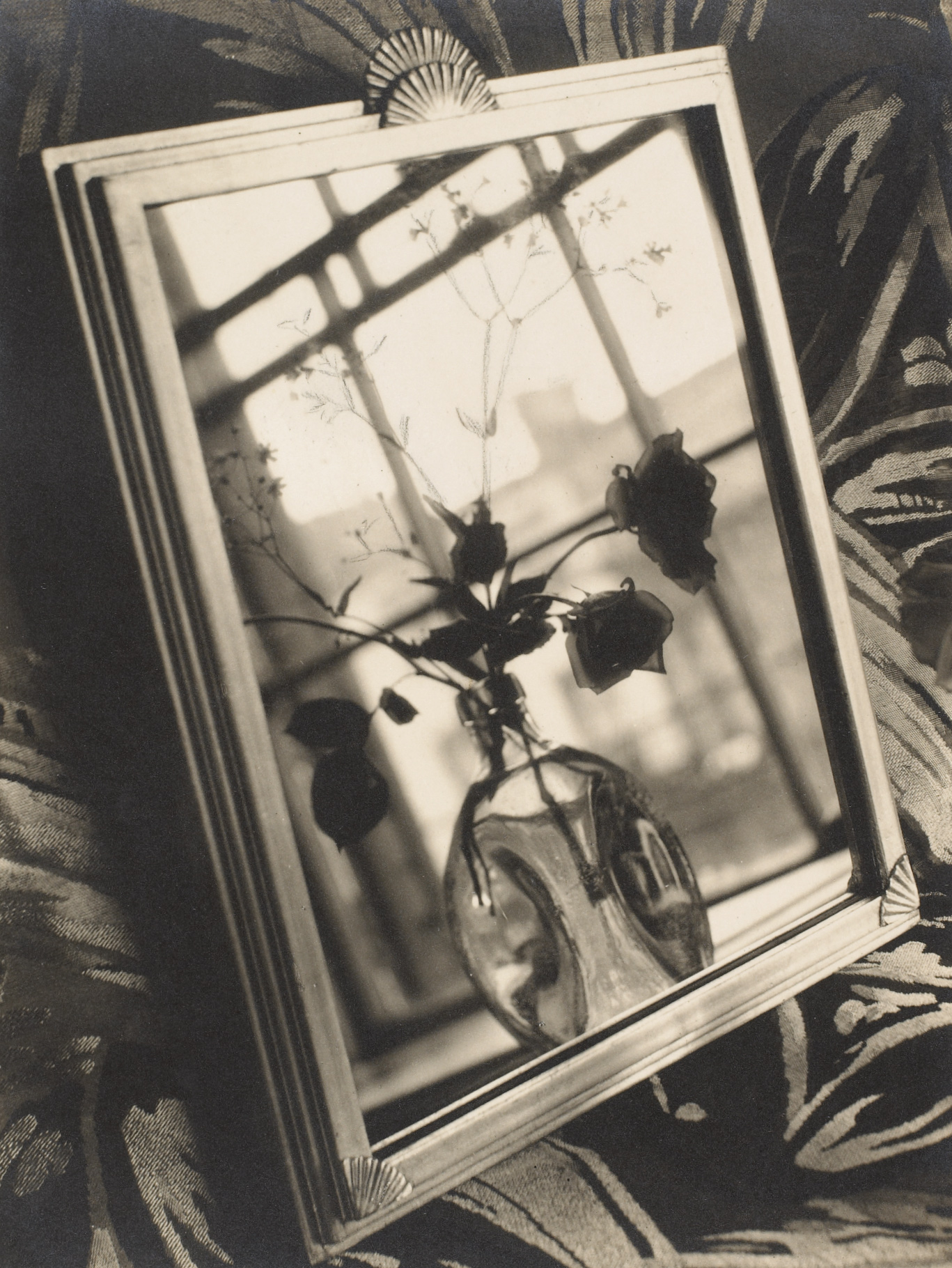

Even though White’s own art practice was Pictorialist and soft-focus—he produced numerous ethereal photographs of family members at home or in nature—his school introduced students to modernist art and graphic design. In 1914, Watkins was taught by the painter Max Weber (1881–1961). For Weber, a photograph was primarily an abstract design, a filling up of two-dimensional space. Watkins penned a poem in gratitude for his teaching and guidance, entitled “A Cubist Ode.” And indeed, her first public notice—a full-page tribute to her photography in Vanity Fair—likened her Design – Angles, 1919, to Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Cubist art.

An Influential Teacher

Clarence H. White and others recognized Margaret Watkins’s strength and originality as a photographer. She was the only woman who had been a student who was hired to teach at the Clarence H. White School of Photography. Between 1919 and 1925, she served at various times as an instructor, an administrator, and a personal assistant to White. She had opened up a new way of photographing everyday life and domestic objects, and she passed that knowledge on to her students. She is now recognized for her instrumental role in the development of American photography. Harold Greenberg, one of the world’s foremost photography dealers, who holds a collection of more than 40,000 prints, has written, “For a long time I have believed Margaret Watkins, along with Max Weber, to be to a very great extent responsible for the emergence of the great American Modern photographers of the 1920’s and 1930’s.”

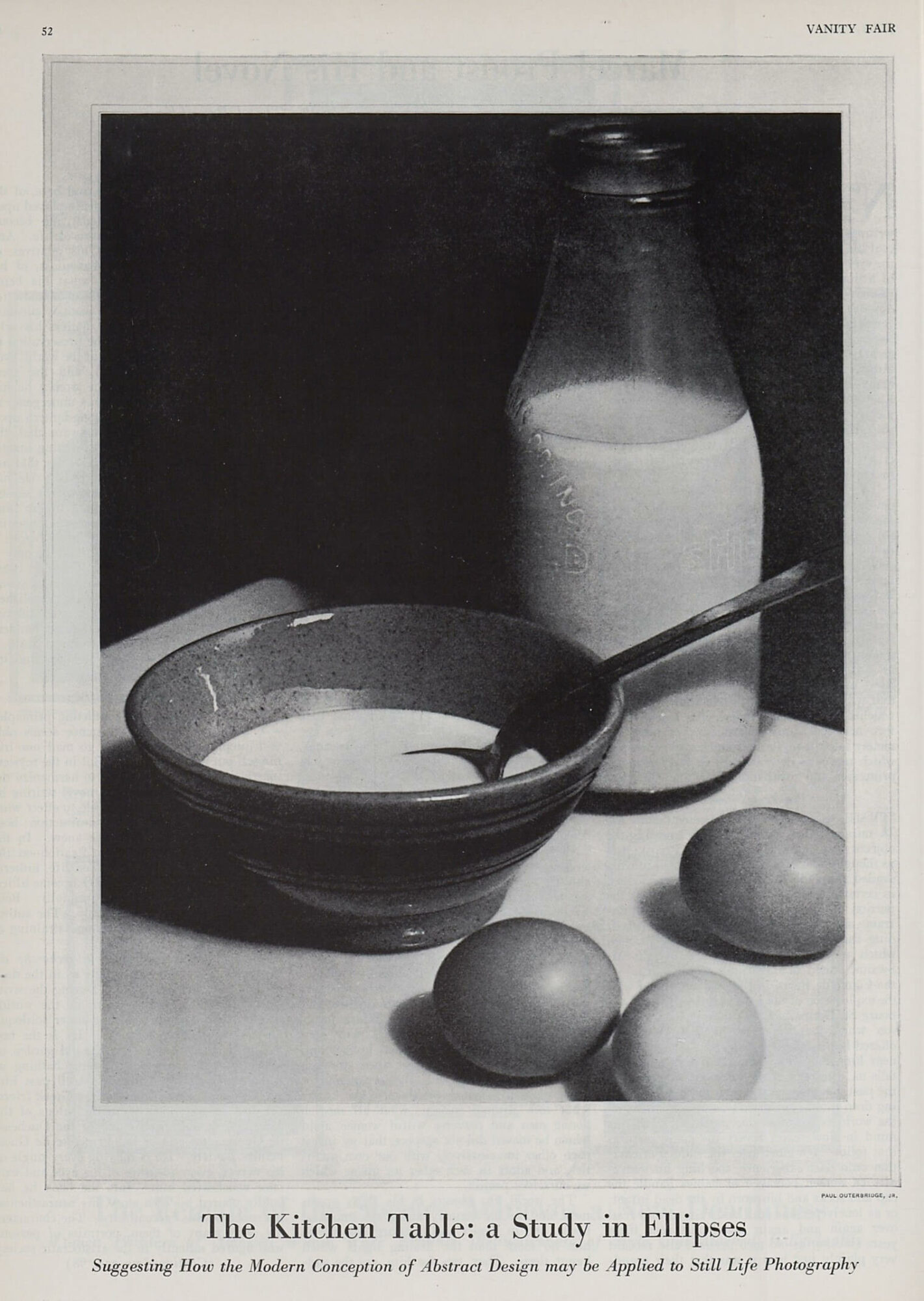

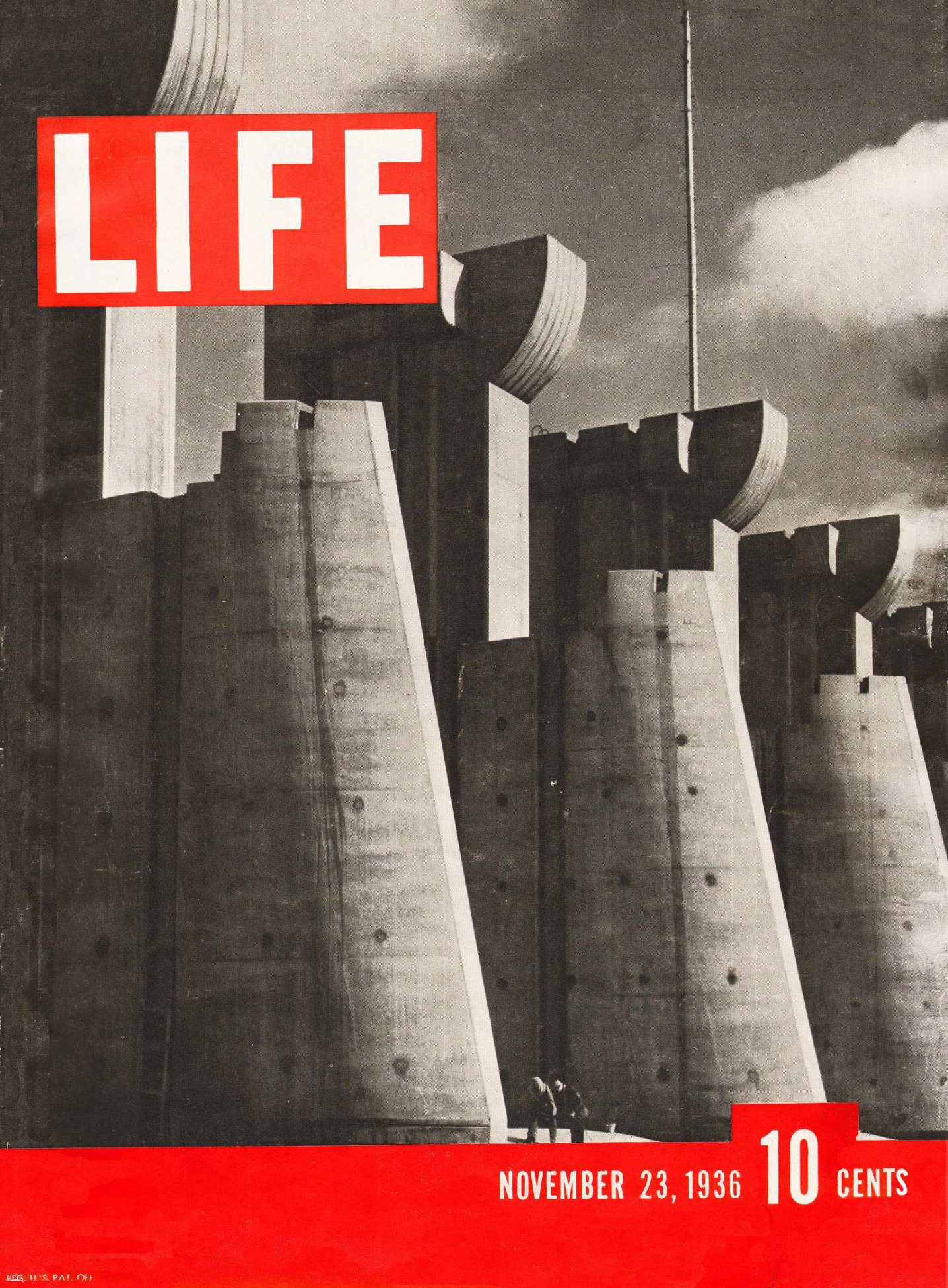

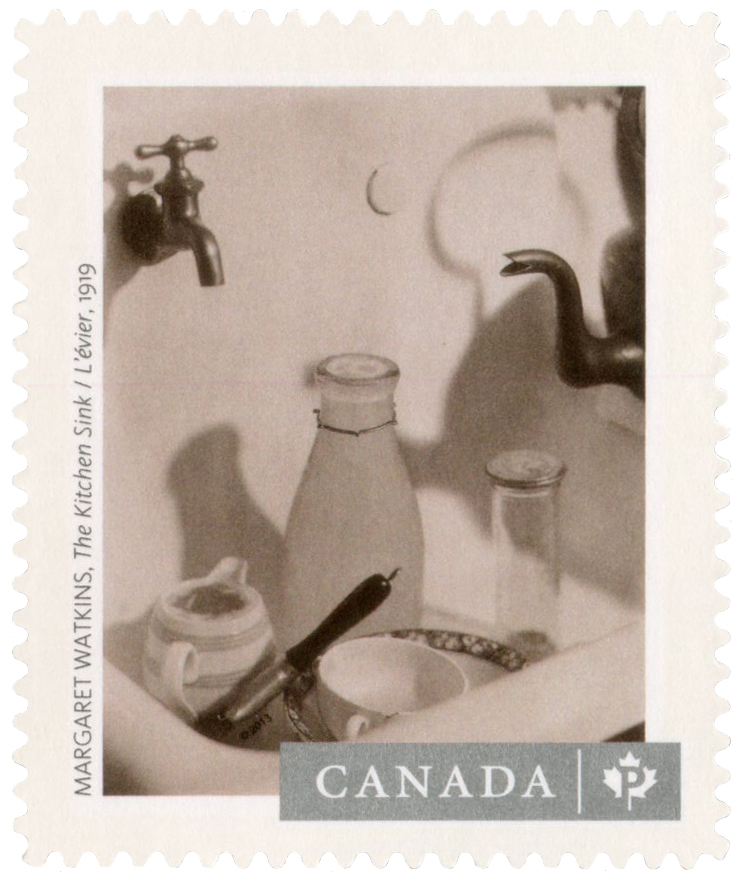

Watkins added the category “Domestic Still Life” to the school’s list of students’ projects and, seeing what their teacher had accomplished with works such as Domestic Symphony, 1919, or The Kitchen Sink, 1919, student Paul Outerbridge, Jr. (1896–1958) later produced his own variation on eggs and milk bottles titled The Kitchen Table, 1921. Her student Ralph Steiner (1899–1986), whose letters to her are affectionally addressed “Dear Watty,” described in a 1980s interview Watkins as an exacting teacher (unlike White, who came in once a week and just “told everybody that they were doing very nicely”). Watkins was “always there”: “a tough dame… a real person to whom you said ‘is this negative over-developed or under-developed’ and ‘my gum prints didn’t come out well, what’s wrong?’” Margaret Bourke-White (1904–1971), perhaps Watkins’s most renowned student, wrote to Watkins in the midst of her Otis Steel Mills work and from the height of her office in the Terminal Tower in Cleveland, saying, “I should love having a chance to show you my beautiful Tower, and have you give the old-time, much-appreciated onceover of my work.”

Watkins’s technical expertise was evidently valued and remembered. Having learned from her, both Steiner and Outerbridge, Jr. were able to translate their domestic still-life work into lucrative advertising careers, and Bourke-White was able to translate modernist forms into epic industrial photography, both in the United States and the U.S.S.R. James Borcoman, former curator of photography at the National Gallery of Canada, called Watkins’s work “revolutionary,” and claimed she would “prove to be an important missing link in North American photography.… As a teacher, she bridges the gap between the modernist movement of Europe headed by [Alfred] Stieglitz and [Edward] Steichen and the later American photographers such as Outerbridge and Steiner.”

Teaching does not simply involve passing on one’s knowledge. Watkins also helped create a welcome space for learning. In the early twenties, she ran the White summer school with Bernard Shea Horne (1867–1933) in Canaan, Connecticut. She offered a collection of her own domestic objects, her treasures found in junk shops, and even clothes inherited from her mother to be housed at the school for students to use. She was singled out by White for her extraordinary contribution to resettling the school in its new location at 144th Street, and even did some carpentering for the school. As an indication of her acknowledged value, Watkins was put in charge of choosing the photographs for the 1925 exhibition by students and alumni of the White school, held at the Art Center in New York.

American Advertising Photography

The 1920s were a time when art and commerce worked easily together. The Arts and Crafts movement had aimed to bring beauty to everyday life and its products and, in that vein, the Clarence White school and the Art Center in New York aimed to make art “useful.” Alfred Stieglitz, with White, had led the fight to promote photography as an art form and not just a documentary medium. But Stieglitz never espoused a link between art and commerce. As Watkins noted, “In the days of the Photo-Secession. . . no devout pictorialist would have deigned to descend to advertising. In their desire to establish photography as an art they became a bit precious; crudeness was distressing, materialism shunned.”

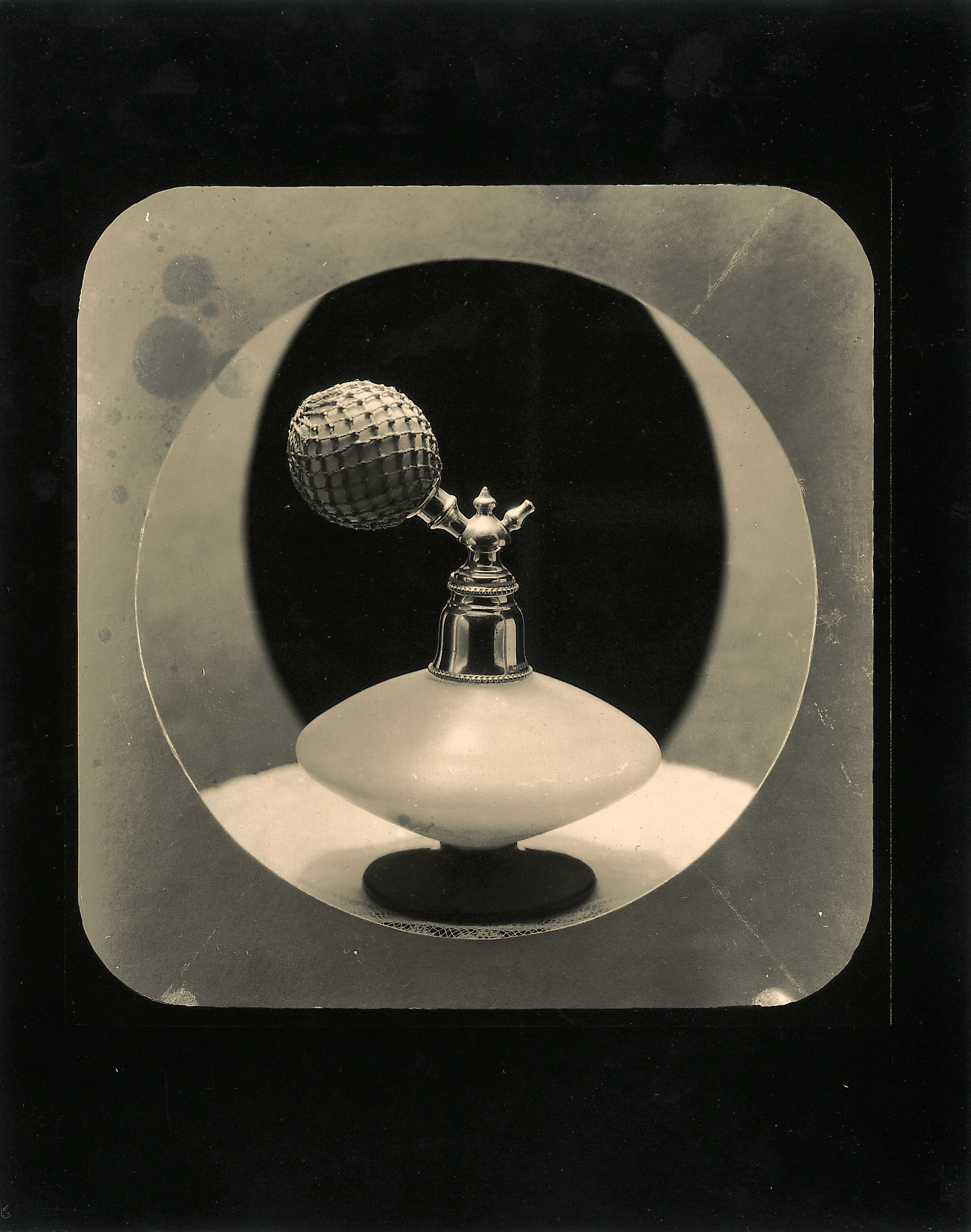

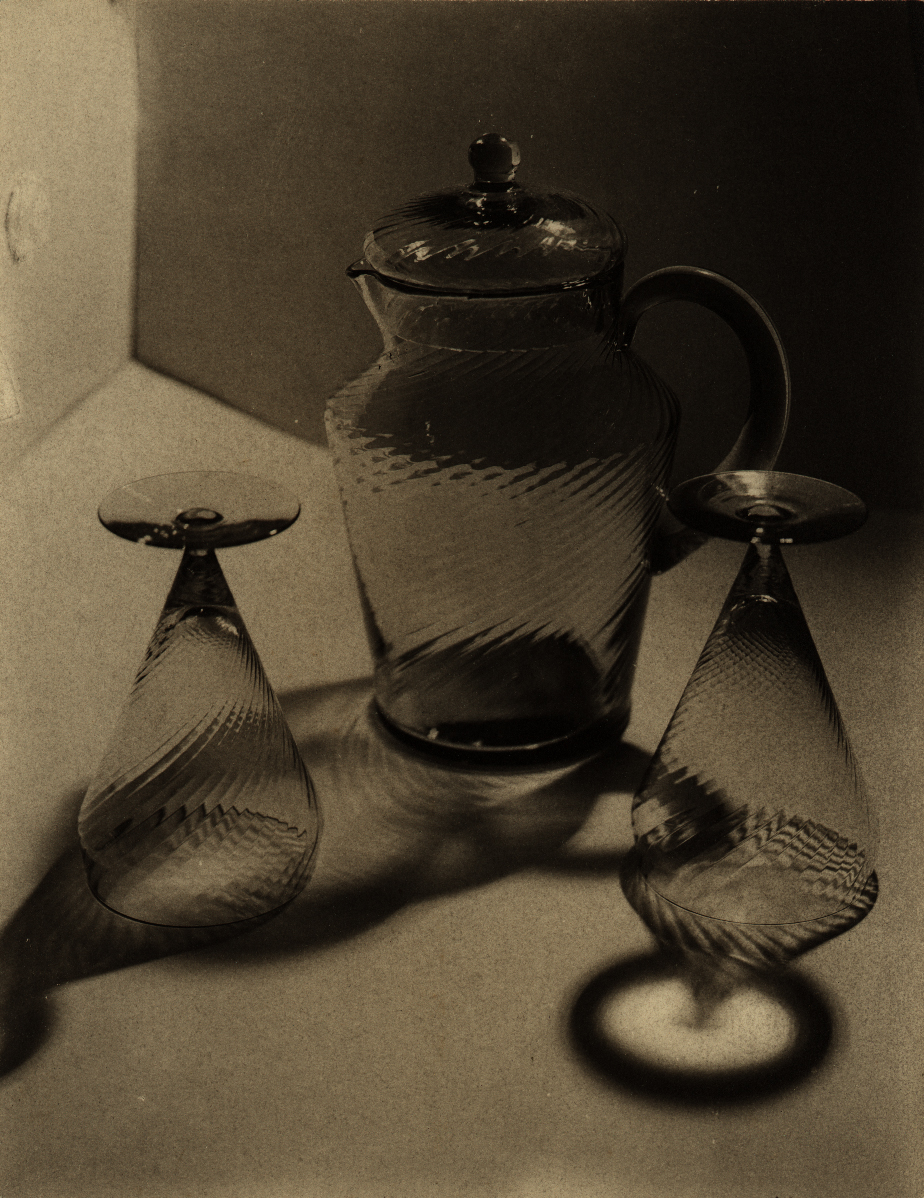

On the other hand, Watkins, along with Edward Steichen (1879–1973) and Watkins’s own students, Ralph Steiner (1899–1986) and Paul Outerbridge, Jr. (1896–1958), were the avant-garde of the new field of American advertising photography. It was at this time that advertising illustration shifted from drawing to photography. The seductive image of, say, eggs on a porcelain sink in Domestic Symphony, 1919, offered a model of how a domestic object might be framed to arrest the viewer. As Watkins wrote in her introductory essay on “Advertising and Photography” for the 1926 Pictorial Photographers of America annual: “Even the plain business man, suspicious of ‘art stuff,’ perceives that his product is enhanced by fine tone-spacing and the beauty of contrasted textures.”

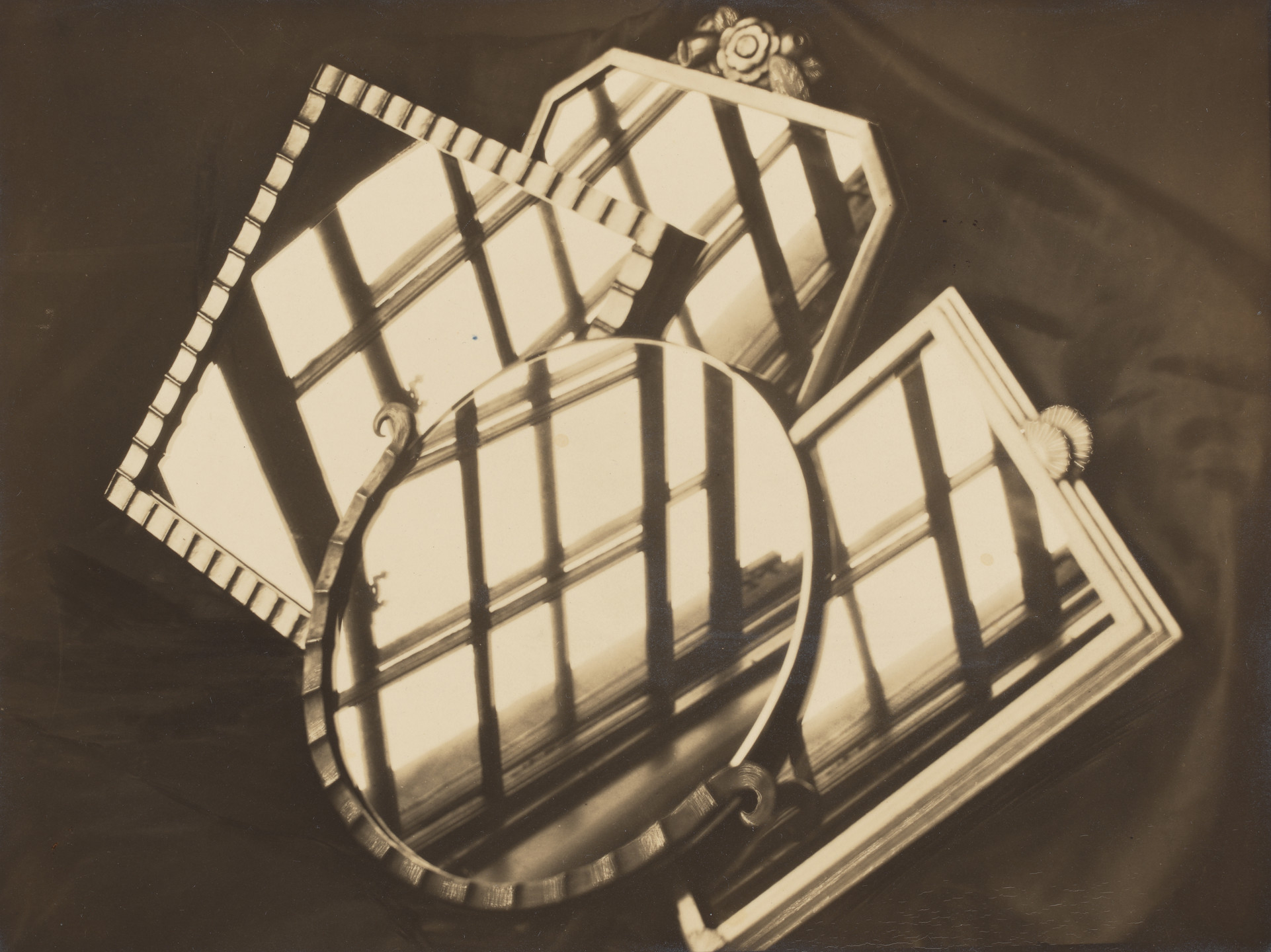

With her domestic still-life images showcased in Vanity Fair, Shadowland, Camera Pictures, the Art Center Bulletin, and Pictorial Photography in America, Watkins’s reputation spread. Art directors and agencies contacted her, asking for examples of her images of glassware or pots and pans. One art director from J. Walter Thompson wrote, “Please take your time on this and bring us the kind of work of yours we all like so well.” He also noted they had tried Steichen but he hadn’t achieved an adequate closeup. Later, Watkins wrote: “I’ve had subjects turned over to me by Art Directors who were not satisfied with fine technique resulting only in a flawless map of the product. It took hours and infinite patience to create a rhythmic whole in line and tone values.”

Between 1924 and 1928, Watkins’s advertising photographs appeared in a range of publications from the Economist to Vogue, featuring objects that ranged from mirrors to Modess sanitary pads. Yet, it is clear that Watkins considered her commercial photographs art. She exhibited them at juried art shows internationally. Her glassware photographs for Macy’s were seen not just in the ads in Ladies Home Journal, but also on the cover of the Art Center Bulletin. This in turn led to an agency in Dayton, Ohio, that represented a glassware manufacturer inviting Watkins to send examples of her still-life studies of glass—a prime example of the Art Center’s usefulness in linking the art world and industry. Heyworth Campbell, an art director with Condé Nast, and on the executive of both the Art Directors Club and the Art Center, praised her work and recommended her for advertising commissions.

While editing the 1926 volume of Pictorial Photography in America, Watkins included advertising photographs: “Though purely commercial,” she wrote, “we feel that they have a distinction and beauty which enable them, to hold their place beside anything in the so-called pictorial section.” This moment of collaboration between art photographers and commercial interests would shift by the end of the decade. White’s original aim to link art to society with the making of beautiful objects, and Watkins’s desire to make everyday life richer through beautiful advertising images, had passed.

A New Woman’s Photographic Language

Watkins’s particular contribution to the history of photography—her creation of a modernist still-life way of representing domestic objects—arose in a specific cultural context. The late nineteenth century saw a shift in women’s lives, offering new employment opportunities and independence. At the same time, with an increase in the immigrant population, new educational methods that encouraged problem solving and creativity aimed to develop independent individuals for a democracy. Urban living and new technologies, such as cars and factory production, coupled with mass production of domestic objects, from nail polish to vacuum cleaners, led to a very new everyday life. Modernist art sought to embody the experience of the machine age and the metropolis using fragmented, disorienting forms. It was a time of inventing the new.

Watkins, with her modernist approach to the camera, was one of a rising number of women photographers around the world creating a New Woman and a new everyday. The Kodak portable camera had been marketed for women (“Kodak Girls”), capitalizing on women’s new independence. Photographic studios provided women with employment, with many women owning and managing their own studios. With developments in printing processes, there were professional opportunities in photojournalism and advertising.

The Clarence H. White School of Photography in New York City was a significant training site for women photographers. Students were asked to complete projects that involved photographing angles or circles by moving out into the world around them to “see” things differently. Watkins walked home through the streets, experiencing the incoherent juxtapositions that the metropolis offers—the screech of the elevated railway, the slush on the ground, the happenstance of a church concert—to her Greenwich Village apartment and photographed the angles and curves of dirty dishes in her sink. Having moved away to escape being “domesticated to death” in the bourgeois home of her childhood, she became an independent working woman and, ironically, returned to her kitchen to rethink and reimagine that space. Using modernist, Cubist strategies, Watkins brought ”photography into the kitchen.” With works like The Bread Knife (Design – Angles), 1919, she was able to reinvent an urban at-homeness that accessed the power of the metropolis, framed objects and spaces in a new way, and offered a female modernism that speaks from within—and against—a gendered domestic world.

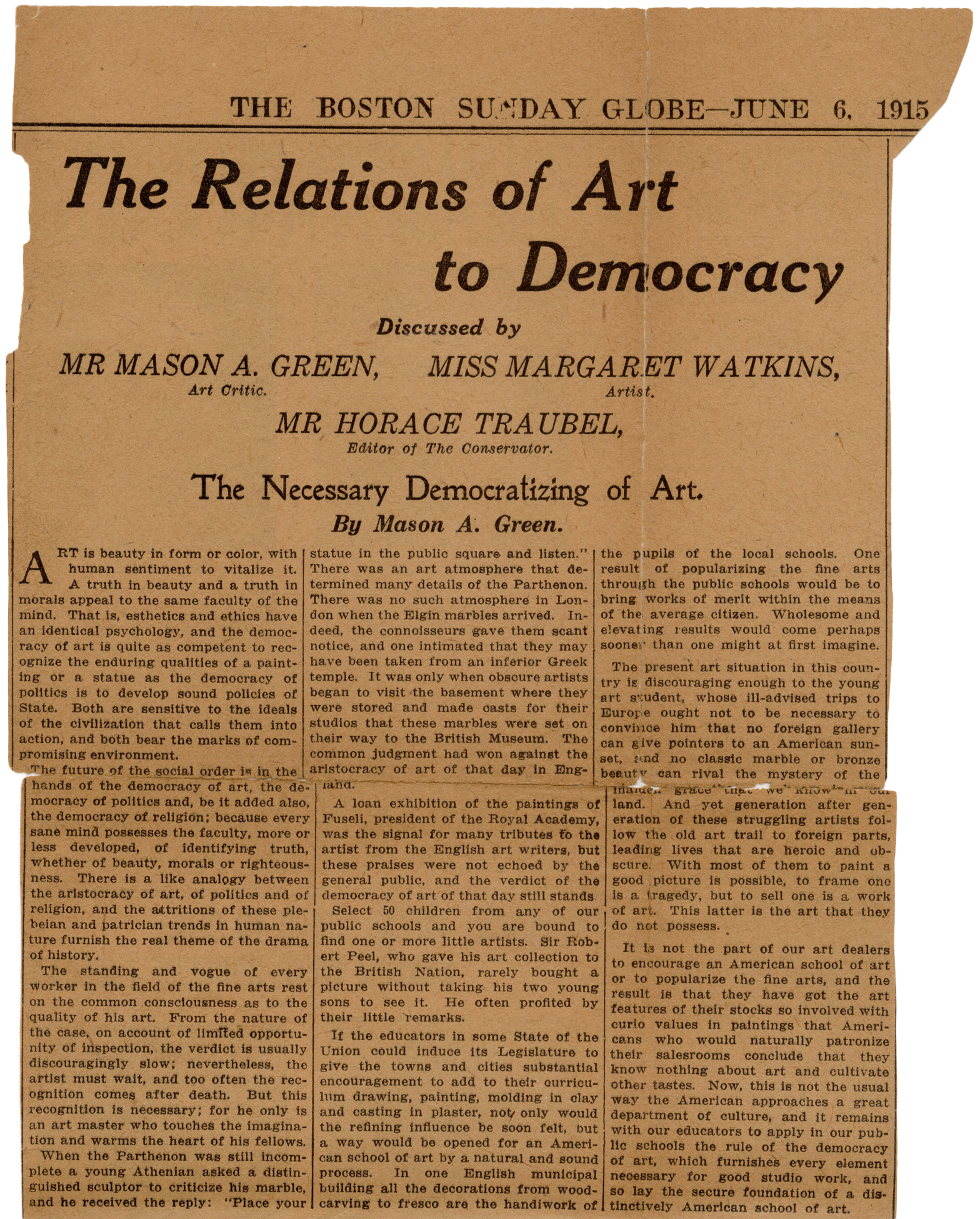

Watkins herself published three significant articles on art and photography that emphasized the confluence of art and everyday life. In 1915, in the Boston Sunday Globe, she joined two prominent figures in the art world, Horace Traubel and Mason Green, to debate “The Relations of Art to Democracy.” In Watkins’s contribution, she argued: “Nothing is ever too commonplace or too useful to escape the sweet embellishing of art.” And thinking of gender and class, she located artistic creativity, production, and appreciation in the lives of people like shopgirls or those living on the “top floor, without heat” who were capable of writing the “inspired essay.”

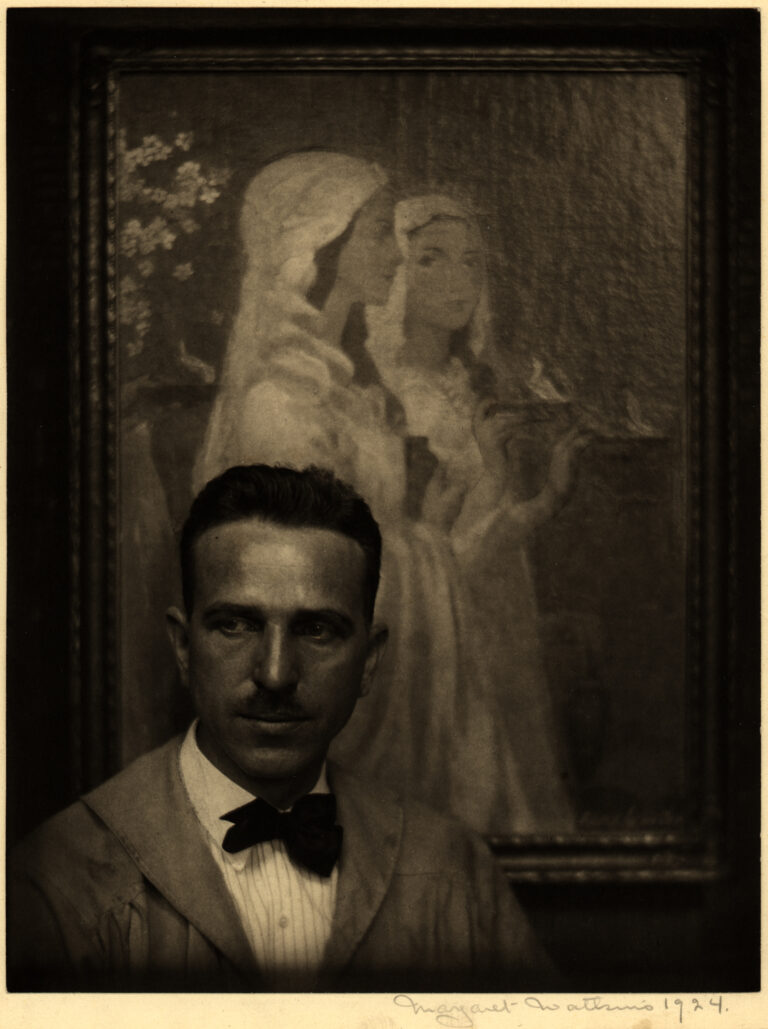

Eleven years later, at the height of her professional career, she was asked to speak about how her art enriched life. Besides admitting her love of the challenge of engaging with her portrait subjects and capturing their characters in her photographs, as well as the pleasure of receiving awards (and cheques) from distant exhibitions, Watkins essentially saw art and the everyday enhancing each other—both the creation of art and the viewing of art to train the eye to perceive beautiful forms. It is as if the everyday is reshaped into ideal forms: “the simplest things take on a new significance, you note the contrasts of light and shade, the subtleties of tone value, feel the interest of related forms and everywhere respond to the rhythm of line, singing as clear as a phrase of music.” So here is not simply the photograph as a document—a mechanical reproduction of an everyday object—but rather a heightened sense of the world, the music that is already there, even in an arrangement of dirty dishes.

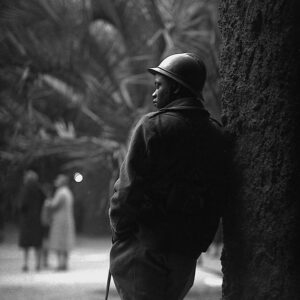

In her 1926 essay “Advertising and Photography,” again she connected art and the everyday: “Commonplace articles showed curves and angles which could be repeated with the varying pattern of a fugue.” Elsewhere, she called for photographs of “common little streets or low-brow vegetables.” And, counteracting a long tradition of portrait photography, she asked for “not pretty girls or character stuff or celebrities but portraits of ‘plain citizens’ good enough to have an impersonal appeal.” Watkins moved into the street in her later European photographs and captured either the surreal contradictions of urban spaces, or the at-times overwhelming sublimity of industrial structures. But in her work of the twenties, she offered the gendered space of the kitchen, its familiar objects and food, in a newly visioned vibrancy, through cropping and blocking of shades of light and dark. As a woman photographer, Watkins developed an original photographic language to represent the modern everyday.

Posthumous Legacy

Often the “business” of making art is left out of art history, but it is the very structures of education, networking, and circulation that determine whether an artist ends up in history at all. A charting of Watkins’s professional relations illuminates how a woman artist was able to have a successful career in the 1920s in New York, and how the lack of networking and institutional support meant that, even though she won first prizes in her new home of Glasgow, she could not make a go of her profession in the U.K. in the 1930s. Watkins’s work was lost to photographic history for almost fifty years. Yet today she is recognized as “a pioneering modernist photographer with a Renaissance flair” and at the vanguard of advertising photography.

At the end of her life in Glasgow, she befriended her neighbours Claire and Joseph Mulholland. She gave Joe Mulholland a large box and made him promise not to open it until after her death in 1969. Her full archive of photographs, contact prints, and negatives were in that trunk. Joe has tirelessly promoted her work since then—in exhibitions and in articles. Light Gallery in New York gave her a solo show in 1986, from which institutions such as the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa and the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, purchased works for their collections.

In 1996, the work of Clarence H. White and his students was showcased in a significant exhibition at the Detroit Institute of Arts and in the accompanying catalogue, Pictorialism into Modernism. Watkins’s work, including her textile designs, was highlighted, and noted in reviews as an important discovery for photographic history. That same year, the Robert Mann Gallery, New York City, mounted a solo show, and at the New York Public Library, Naomi Rosenblum’s exhibition, based on her 1994 book A History of Women Photographers, included Watkins. Since then, there has been a detailed monograph on her life and work by Mary O’Connor and Katherine Tweedie (2007), and two important retrospective exhibitions and catalogues: Margaret Watkins: Domestic Symphonies, 2012, from the National Gallery of Canada and Margaret Watkins: Black Light, 2021, from diChroma Photography in Madrid. The latter exhibition and the laudatory press it received have now given Watkins European fame. The recent significant exhibitions (and catalogues) Clarence H. White and His World,

2017–18, and The New Woman Behind the Camera, 2021–2022, have included Watkins, highlighting her importance as an advertising photographer, a teacher, and an agent in the move from Pictorialist to modernist photography. Watkins has fully regained recognition in photographic history.

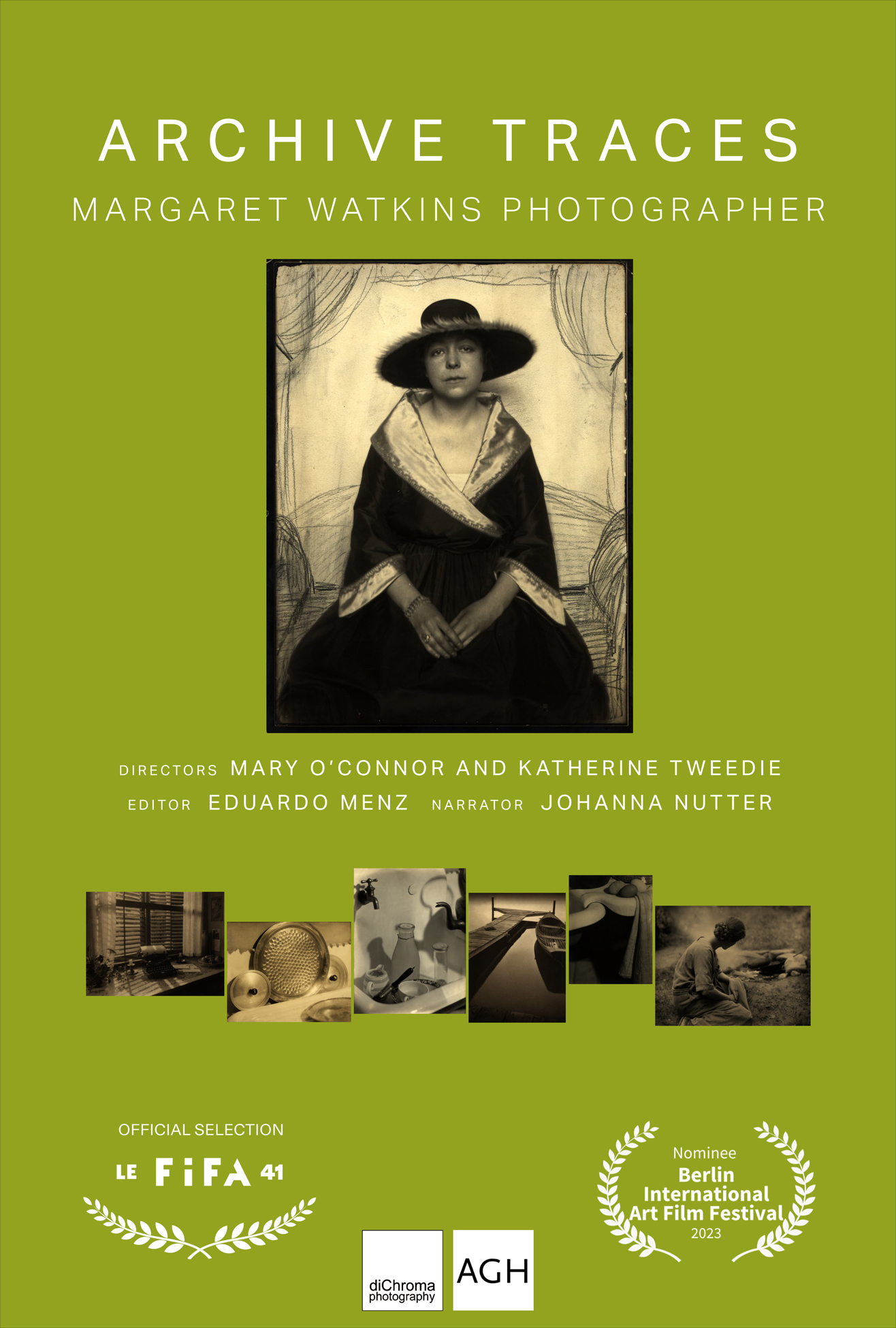

In Canada, Watkins’s importance was marked in 2013 with a postage stamp of her work The Kitchen Sink, 1919. Considered one of seven “ground-breaking Canadian photographers over the past 150 years,” she was noted for her still-life and advertising work. Watkins’s posthumous solo shows have been shown in multiple cities in Canada, and she has been included in major group shows, such as Uninvited: Canadian Women Artists in the Modern Moment, 2021–22. The short documentary Archive Traces: Margaret Watkins Photographer (2022), made for the Art Gallery of Hamilton, has shown at the Festival International du film sur l’art in Montreal (FIFA), as well as other international festivals, and was streamed on FIFA’s website in 2023.

Margaret Watkins continues to be remembered for her contributions to the genres of domestic still-life and advertising photography, and her discoveries of new ways of seeing everyday life—both its objects and, in her European photographs, its street scenes. She also pushed the constraining social boundaries of class and gender, both in her life and in her art. Her photographs are recognized as key works in the history of modernist photography and early advertising photography, and still speak to cultural and social concerns today.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements