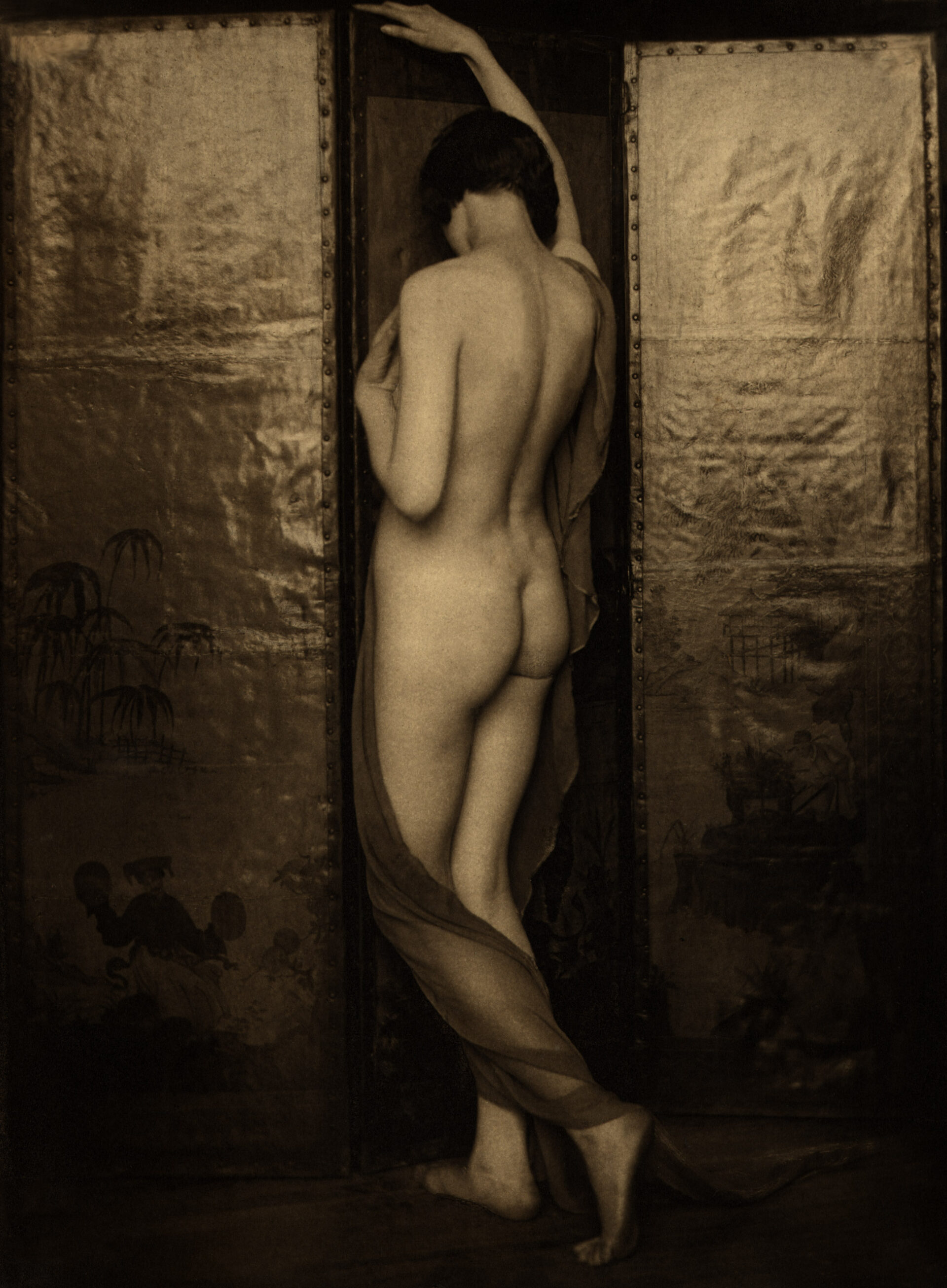

Tower of Ivory 1924

Margaret Watkins, Tower of Ivory, 1924

Palladium print, 21 x 15.8 cm

Various collections

Margaret Watkins’s Tower of Ivory is structurally original both in arrangement of tonal values and repeating curves of the body. It sits within the tradition of Western art’s representation of the female nude. Yet its publication as an image of a healthy body asks us to look again to find not the passive recipient of the male gaze, but the strength and supple movement of a professional dancer.

She exhibited Tower of Ivory in 1924 at the Frederick & Nelson Annual Salon of Pictorial Photography in Seattle and at the International Foto-Tentoonstelling in Java. The upright nude figure, turned three-quarters away from the camera, forms an s-curve from her raised right arm over her head to her left foot extended behind her. The lines of her neck, arms, spine, buttocks, and legs form gentle repetitions of this curve. The standing nude is framed by two Chinese screens, structurally moving the viewer’s eyes to the curving lines of the body. Their blocking is shaded in tonal gradation forming the base of a triangle of light that moves from the top of the screens, narrowing down to the feet at the bottom, slightly broken by the diaphanous tulle on the woman’s calves. The weight, entirely on her right leg, conveys stability and strength, even while the body is curved and supple.

-

Margaret Watkins, Head and Hand, c.1925

Palladium print, 20.7 x 15.7 cm

The Hidden Lane Gallery, GlasgowThis work was shown at the London Salon of Photography in 1928.

-

Margaret Watkins, Reclining Nude, 1923

Palladium print, 16.5 x 21 cm

The Hidden Lane Gallery, Glasgow -

André Kertész, Satiric Dancer, 1926

Gelatin silver print, 24.8 x 19.7 cm

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles -

Margaret Watkins, The Back of A.Z.W. [Woman by the campfire], c.1914–23

Platinum print, 16.2 x 21 cm

The Hidden Lane Gallery, Glasgow

The model, Marguerite Agniel, was a dancer and health advocate who chose a number of Watkins’s photographs of her for her book The Art of the Body (1931). As a “tower of ivory,” the image suggests strength. Agniel chose it to illustrate correct posture and “the Graceful Suppleness of the Back.” Once again, one sees Watkins’s photographs circulating in different spheres with different meanings. As an image in a Pictorialist exhibition, it shows the subtlety of tonal gradation and the traditional beauty of the female nude. In a health book, it suggests the work that must be done to achieve an ideal, healthy shape.

Watkins’s Head and Hand, c.1925, offers a sensuous appeal comparable to Tower of Ivory: in this case, with a sense of playful if not surreal irony, seeing that it is Agniel’s hand holding a sculpture of her own head. Another of Watkins’s nudes also turns her figure into a geometric form, this time undoing any soft s-curve, with its arms and legs as parallelograms, and resisting an idealized female body. Watkins exhibited Reclining Nude in her 1923 solo show at the Art Center in New York, anticipating the 1926 Satiric Dancer by André Kertész (1894–1985), a seminal photographer of the twentieth century known for original angles and points of view.

The Back of A.Z.W., c.1914–23, a Pictorial, slightly soft-focus photograph, might be compared to Tower of Ivory. The silhouette of the woman’s face and neck have the quality of the rounded forms of traditional nudes. Yet she is clothed in a working smock and leather boots. This is a working woman—she is cooking something on the campfire—but the viewer is shown a pause in that labour, a moment of thoughtfulness and interiority. There is both a heft and a lightness to her body. She is present, embodied, a possibly complex being that the viewer is invited to follow into imagining her thoughts, worries, and dreams. Rather than looking at a sublime landscape vista, the viewer looks with this woman, who has a moment to stop, look, and think, despite or along with the daily labour that is visually present as the pan in the fire. Here is an alternative everyday for women, and an alternative to the traditional representation of a female nude.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements