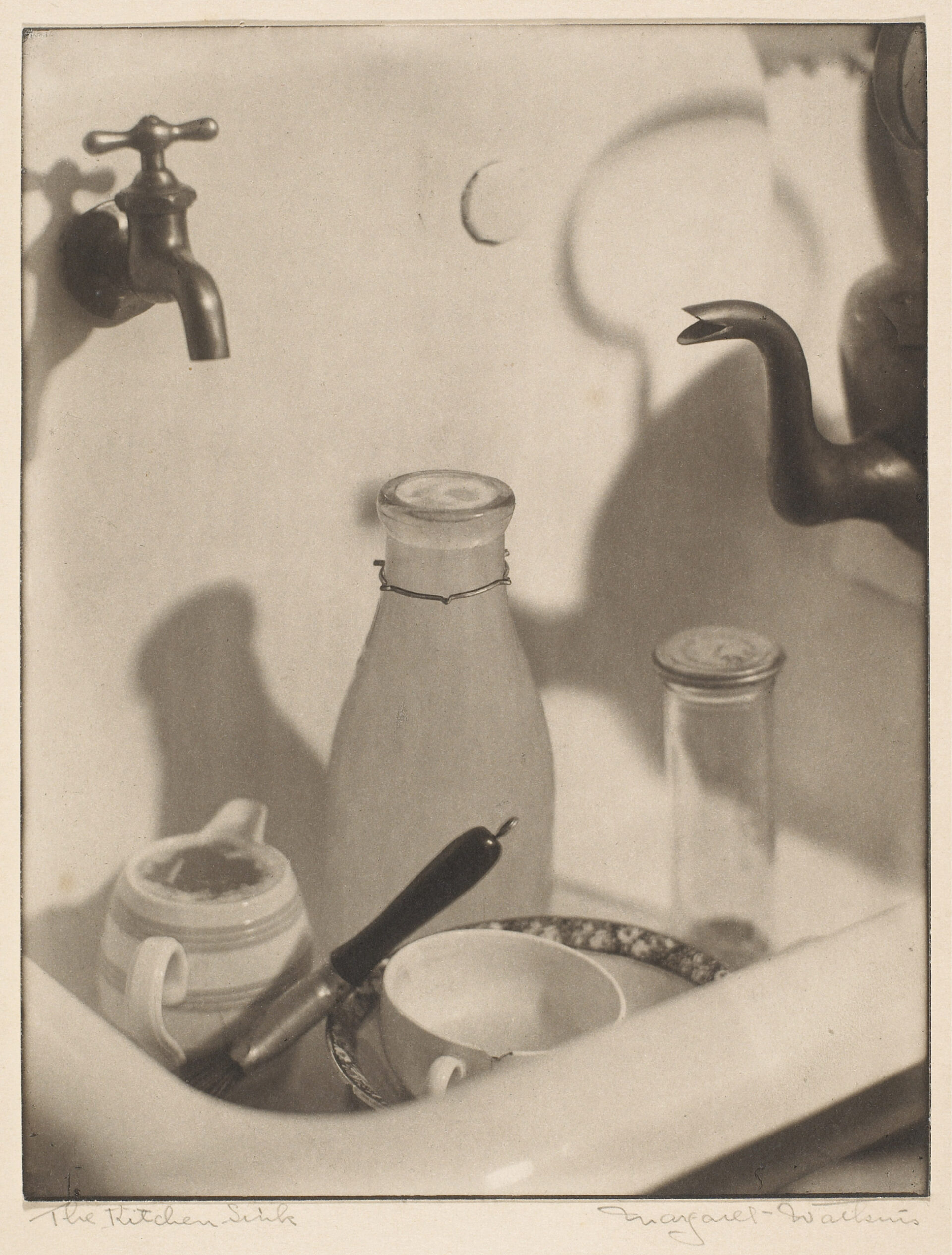

The Kitchen Sink 1919

Margaret Watkins, The Kitchen Sink, 1919

Palladium print, 21.3 x 16.4 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Margaret Watkins’s The Kitchen Sink is a photograph of dirty dishes sitting in a sink—with scum on the milk bottle at its centre, surrounded by mismatched and chipped crockery. The sink’s curved edge, cropped at an angle, gives the photograph a diagonal plane. The eye takes in the shiny metal objects—the faucet, the spout of the kettle, and the cleaning brush—all carefully situated to form a centring triangle that contains and frames the objects. The shadow of the kettle’s handle on the porcelain sink and a recessed backsplash produces a floating, disorienting line reminiscent of abstract paintings by the Russian Expressionist artist Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), while the milk bottle’s shadow looks as if it would receive the water if the tap were turned on. The palladium print produces a range of rich tones, from dark, through multiple greys, to almost white.

This, Watkins’s most renowned (and infamous) photograph, was exhibited from 1921 to 1924 in New York, San Francisco, Japan, and London. In 1922, it won second prize at the Emporium Second Annual Photographic Exhibition in San Francisco and was praised for its technique and “pleasing combination of pattern founded on a geometrical base.” The prize brought with it much public criticism and even parody. The photograph is an excellent example not only of her focus on design, but also of her daring—National Gallery of Canada photography curator James Borcoman called it “revolutionary”—use of seemingly unaesthetic, domestic materials.

The Kitchen Sink controversy was over gender and representation in art, particularly in relation to what constitutes a suitable subject. Whereas sexually exploitative and often violent representations of women had long been considered noble subjects of Western art, dirty dishes were not. In London, one reviewer pointed out that the photo was “not one that ‘anyone would beg to contemplate in his dying moments.’” To another reviewer, The Kitchen Sink was “a record of slovenly housekeeping,” even as it was “an exemplar of splendid technique… the depiction of some misplaced crockery and clever composition of triangles.” A parodic poem appeared in Camera Craft: “The Old Kitchen Sink: With Apologies to Margaret Watkins,” where, stanza after stanza, women were expected to stick to the kitchen and let men do the real work of photography. In response to a critic who complained that the photograph suffered from “containing too many objects of equal interest,” Watkins noted, “Evidently the poor duffer knows nothing of Modern art—abstractions, pattern rhythm etc. The ‘objects’ are not supposed to have any interest in themselves—merely contributing to the design.” Here is Watkins arguing that The Kitchen Sink is pure abstraction. Nevertheless, it is precisely the shocking combination of “essential form” and material reality that is her gift. At times in her life, Watkins felt “domesticated to death,” but working in and through her domestic spaces, she was able to develop a woman’s photographic language of the everyday.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements