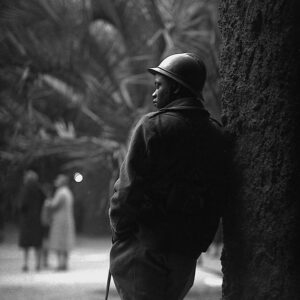

Self-Portrait 1923

Margaret Watkins, Self-Portrait, 1923

Gelatin silver print, 21.4 x 16 cm

Various collections

Watkins offered this striking self-portrait, with head held high, to accompany a newspaper article on her work. The photograph is important both as an original portrait and as a biographical document. Here, she looks down at the viewer, a confident subject. There is no makeup, no feminine coy charms or enticements, no eyes downcast. She takes control of her interaction with the viewer. The long neck is reminiscent of the portrait by Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879) of Julia Stevens (Virginia Woolf’s mother, also known as Julia Jackson), and indeed Watkins did produce a beautiful portrait of her friend, Verna Skelton, in this vein. However, her own self-portrait does not include the turned head in an act of silent contemplation. Instead, it actively invites a conversation. She called the photograph “soulful,” but insisted she had figured out an “an Ingeniously Devised Mechanism” (one she never divulged) to take the picture. Here is a modern woman who is inventing technology to create her art. The work is complemented by the last line of the autobiographical letter in which this photograph was enclosed: “and as a flippant finale, I love cheese and I do my own carpentering.”

-

LEFT: Julia Margaret Cameron, Mrs. Herbert Duckworth as Julia Jackson, 1867

Albumen silver print, 32.8 x 23.7 cm

Gilman Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkRIGHT: Margaret Watkins, Verna Skelton, 1923

Palladium print, 21.2 x 16.3 cm

The Hidden Lane Gallery, Glasgow -

LEFT: André Kertész, Mondrian’s Glasses and Pipe, 1926

Gelatin silver print, 15.7 x 18.2 cm

Various collectionsRIGHT: Margaret Watkins, Untitled [Jane Street, New York City], 1919–25

Platinum print, 21 x 16 cm

The Hidden Lane Gallery, Glasgow

When this self-portrait appeared in the New York Sun and Globe to signal her upcoming solo show at the Art Center, mascara, eyeliner, and lipstick had been added and it was placed in an oval frame. Infuriated, Watkins wrote on the back of the photograph: “To ye engraver / Don’t clip, prune / or place this in an oval / Neither retouch & paint / To the semblance of a / Snake-eyed vamp!” The editors of the newspaper had changed the meaning of the portrait. Watkins’s original portrait and her response to the newspaper insist on her identity as an artist and a professional, not a femme fatale.

Although Watkins could write in moments of self-reflection, “Funny isn’t it how we are all absolutely alone inside of ourselves! Just a skein of wool—all tangled up never been properly wound,” this “soulful” self-portrait offers strength and directness. This is the professional woman who has been written up in Vanity Fair and is about to have her own first solo show in New York City. This is the woman photographer who is fully conscious of what it means to gaze through her viewfinder, to see the world in her own way and see it anew. She is one of several women who were taking up the art of photography to earn a living. While the old amateur camera clubs often only welcomed male members, schools such as the Clarence H. White School of Photography encouraged women to learn the art as a profession in their own portrait studios, in photojournalism, or in advertising.

On another occasion, in line with other avant-garde artists of the time such as Man Ray (1890–1976) and later André Kertész (1894–1985), Watkins represented herself through objects in Untitled [Jane Street, New York City], 1919–25: her hat, gloves, and purse on her sofa, art reproductions on the wall, and the wall itself. In an interview at the time, she said she was “studying this wall. It is very beautiful when the light plays on it in certain ways.” This was a portrait of an artist at home.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements