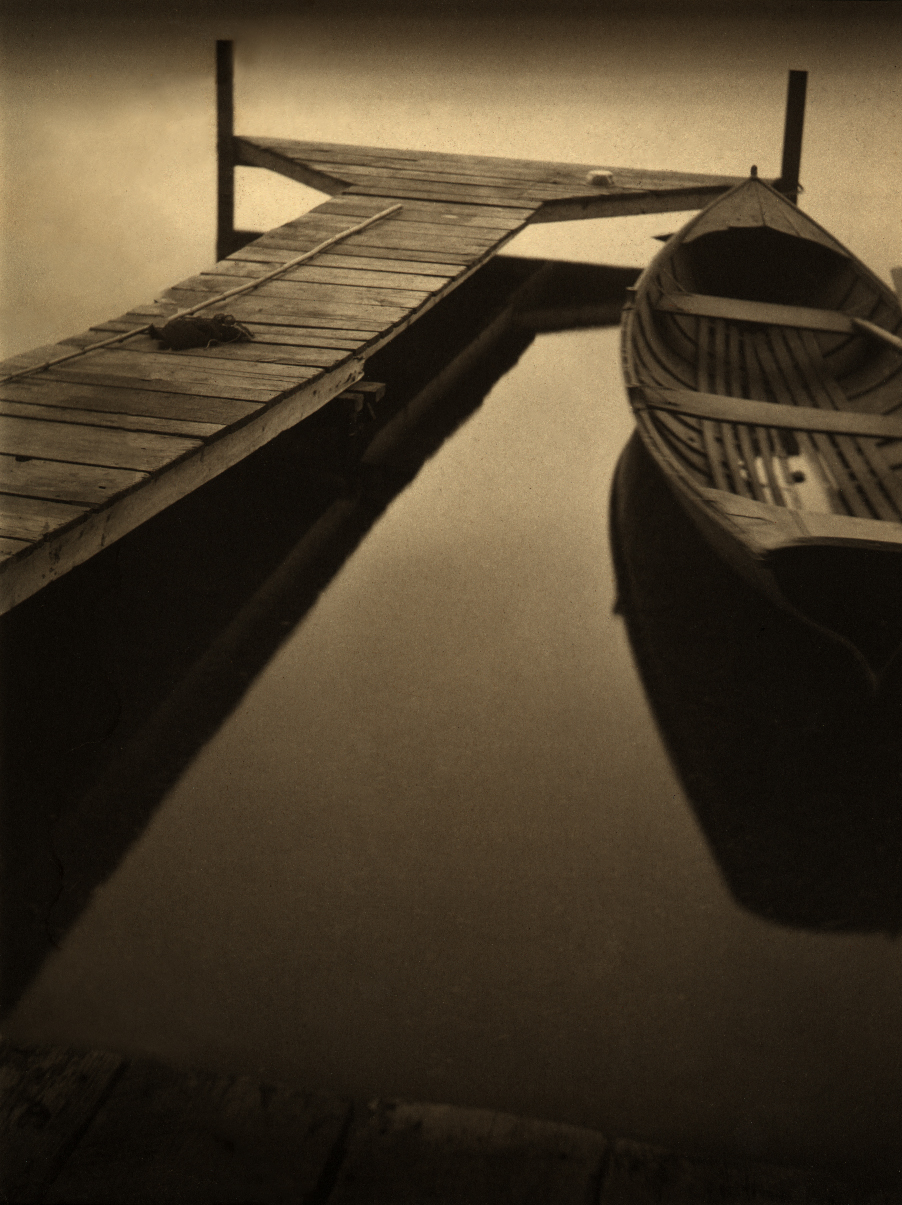

Opus 1 1914

Margaret Watkins, Opus 1, 1914

Bromide print, 30 x 23.3 cm

The Hidden Lane Gallery, Glasgow

In the summer of 1914, Margaret Watkins took the photograph Opus 1 at the Clarence H. White Seguinland School of Photography in Maine. One of her earliest works, it can be argued that it holds the essential foundation of the style she developed over her entire photographic career: finding geometric form—angles, curves, repetitions—in her everyday world.

Watkins had begun to learn photography in Boston the year before, working as an assistant with the American photographer Arthur L. Jamieson at his portrait studio. However, the six-week summer course with Clarence H. White (1871–1925) shaped her art practice. White was an advocate for the recognition of photography as art and had been teaching Pictorial photography in the art department of Columbia University’s Teachers College and the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences. By choosing the title Opus 1, Watkins signalled her intention to present this as her first work of art. The title also suggests she saw links between her photographic work and music, having trained as a pianist and a singer.

Opus 1 is a brilliant patterning of angles made out of the rounded sides of fishing boats. There are triangles everywhere: in the bows of the boats, in the shape formed by an outstretched arm and the shadow it projects, and, significantly, in the centre of the composition. Watkins moves the objects to the edges of the photograph, leaving the various tones of the rippling water in the centre—tones that include a dark curve that mirrors and echoes the rowboat’s edge on the right.

But a note on the back of the photograph also speaks about more than triangles. She writes that she was standing on the half deck of a boat watching the netting of small fish used for baiting larger fish like hake or halibut. Opus 1 might be considered a landscape photograph, but it does not give us a horizon. We are thrown into the thick of it—the water, the labour (the arm stretching), and the messiness of it all with the fish and the baskets. Despite her later insistence that, in modern art, what you depict has no relevance, it is the form that counts, Watkins was always, also, interested in what she saw. It is the interplay between form and the seemingly insignificant, often domestic, objects that gives us her original vision. Here, in her first photograph, she wanted us to know what the workers are doing, where she is standing, and what fish are in the boat.

Eight years later, Watkins took another photograph of boat and water that is closer to her stated ideal of pure form. In The Wharf, 1922, the photograph’s subject consists of two objects that meet near the top. Again, the compositional centre is a void. The almost imperceptible horizontal dock at the bottom of the work completes the off-centre triangle of the water. The paring down of objects and focus (again, no distracting horizon) and mirror-calm water create a silent, meditative world. Watkins was interested in something beyond the soft-focus lens of Pictorialism. The Wharf shows her ultimate mastery of dark and light space, the fragmented geometric shapes of Cubism, and the evocation of mood.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements