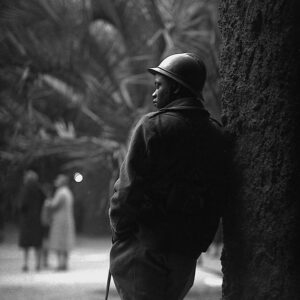

Moscow [Youth Festival] 1933

![Moscow [Youth Festival]](https://www.aci-iac.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/margaret-watkins-moscow-youth-festival.jpg)

Margaret Watkins, Moscow [Youth Festival], 1933

Gelatin silver print, 15.6 x 21 cm

The Hidden Lane Gallery, Glasgow

Margaret Watkins travelled to Moscow and Leningrad in 1933 with a small group organized by the Royal Photographic Society of London. Drawn to Soviet art and film, she, like her student Margaret Bourke-White (1904–1971), wanted to be one of the first to witness the Soviet attempt to “industrialize almost overnight.” This Moscow image of Youth Festival posters is one of twenty-five prints Watkins prepared from this expedition.

This streetscape is a busy photograph, with much to sort through and organize visually. Watkins’s eye isolated the horizontal rows of light and dark—the base of the street, the lower level of windows mixing with the tables in the lower part of the three posters, an upper level of dark windows and flags, and, finally, a dark-toned roof. All the while, there are verticals of people, posters, windows, and flags. But within this patterning (essential to her aesthetic) are two important narrative elements: first, the three gigantic posters depicting three designers (notably, one a woman) at their drafting tables; and second, at the lower left of the photograph, the group of women waiting for a tram. They in turn stand in for the half-hidden pedestrians passing between the building and the posters.

Reading the three posters, it is at first unclear if they are hanging from the building, or, as is the case, standing in the street towering over the scene. This is the world of Soviet montage propaganda. The posters are inspiring in their own beautiful design of repetitions with variations: in what is drawn on the table, in the drawings at the designers’ backs, in their smocks, in the position of their heads, in the blocking of light and dark, paralleling the tonal pattern in Watkins’s own photograph, and in their use of the photograph within illustrations. Always alert to the role of images in our world, Watkins acknowledged the Soviets were masters of propaganda, documenting numerous Moscow and Leningrad instructive posters, promoting working together and pulling your weight, the dangers of inebriation, or keeping healthy.

The women waiting for the bus, seemingly minor but essential figures in this photograph, remind the viewer of the relation between the posters and the real workers. Seen through one lens, these women are the heroes of the story, while the posters celebrate idealized versions of their labour. Seen though another lens, these women with their tell-tale white and dark babushkas are the embodiment of real labour and struggle against the aspirational posters that do not speak of the pain and poverty that Watkins witnessed during her visit.

Another photograph, The Builder, “Peter the Great,” 1933, captures the relation between public imaging and the people in the street. Watkins situates the monument to Peter the Great in relation to two boys in shallow water below. The photograph is patterned in three horizontal tonal bands, but a triangle unites the three figures with their shadows, even their legs echoing each other. It is a stopping of time, a “decisive moment,” much as the photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908–2004) would do later in the 1940s and 1950s. But this photograph brings the monumental figure down to the level of the everyday.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements