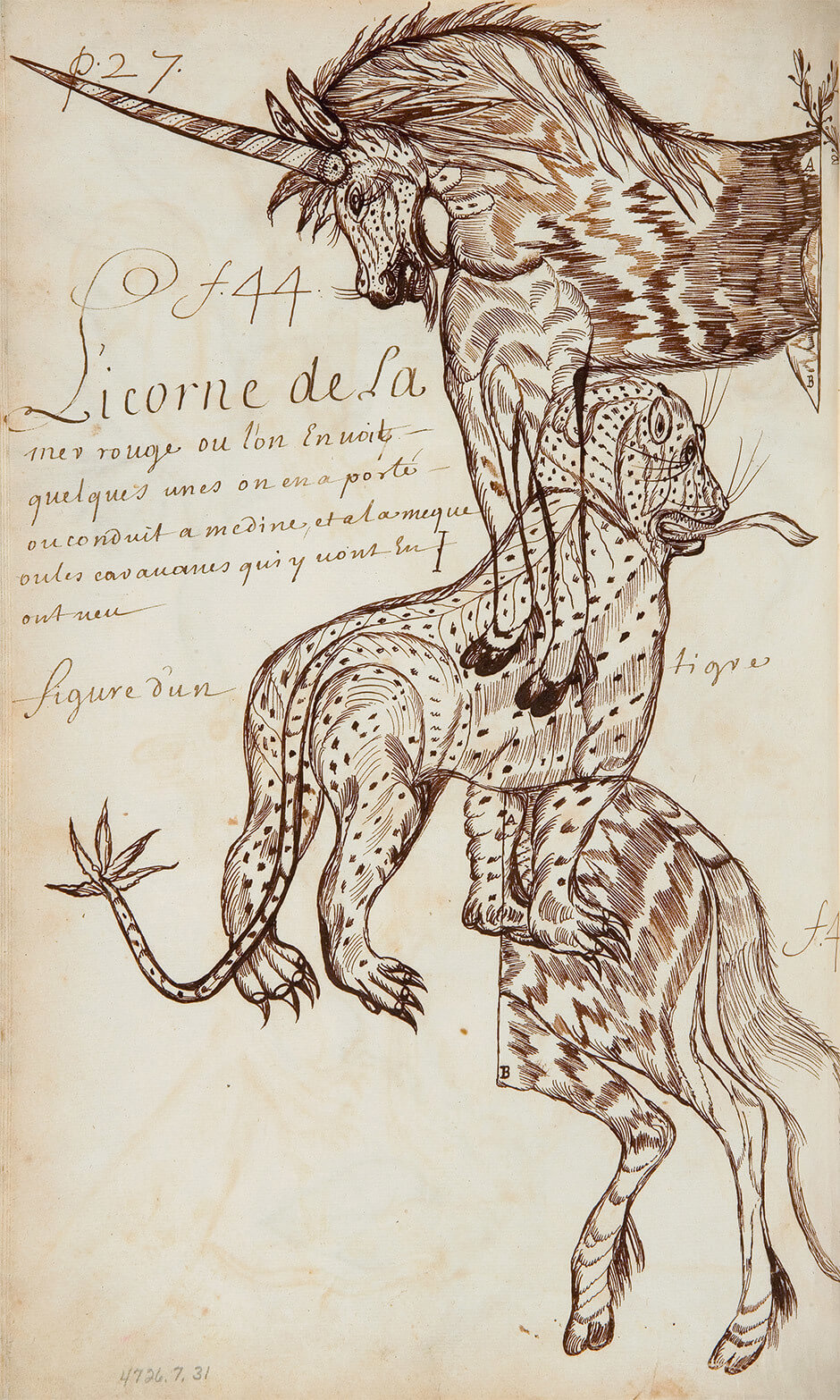

Unicorn of the Red Sea n.d.

Louis Nicolas, Unicorn of the Red Sea (Licorne de La mer rouge), n.d.

Ink on paper, 33.7 x 21.6 cm

Codex Canadensis, page 27

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

In his Codex Canadensis, Nicolas begins the section on the wildlife he observed in New France with this extraordinary depiction of a tiger and the mythological unicorn. Curiously, the image of the unicorn is divided in two parts and labelled A and B. Nicolas probably miscalculated the space he had to draw in and expected that readers would join up the front and back sections of the animal in their imaginations. The tiger is found in between the two parts of the unicorn, and is covered in spots, rather than stripes. Europeans were not familiar with the tiger at the time. What the sixteenth-century French writer Michel de Montaigne claims to have seen in a menagerie in Florence and calls a “tiger” could have been a leopard or an ocelot. Nicolas was certain that unicorns existed and insisted he had seen one killed. But he also knew that neither the unicorn nor the tiger were native to the New World. So why would he include these animals in a book about New France?

Nicolas liked to begin or finish a grouping of similar species with an image he considered “monstrous” or “worth showing”—in the original meaning of the word monster, derived from the Latin word monstrare, to show—regardless of whether it was indigenous to North America. For the section on animals, the unicorn plays a similar role to the illustration of the passion flower (passiflora), which concludes the section on plants. Although this plant does not grow in Canada, it has religious significance as a symbol of the Passion of Christ. By including the unicorn among his animals, Nicolas may have been influenced by the fact that the Scandinavians sold narwhal tusks in Europe as unicorn tusks, claiming they had special healing powers.

Paradoxically, Nicolas used the example of the unicorn to emphasize the importance of direct observation over purely bookish information. The creature would disparage “les gens de cabinet” who didn’t believe in unicorns simply because they had never travelled outside their parish. As he wrote in the The Natural History of the New World (Histoire naturelle des Indes occidentales):

I do not know what to say about the appalling error that has crept in even among many learned people who are otherwise very knowledgeable, but have seen nothing of the admirable things produced by nature because they have never lost sight of their parish church tower, and who hardly know how to get to the Place Maubert or the Place Royale without asking the way. I say that these people are stubborn to insist that there is no unicorn anywhere in the world.

In the ten crowded pages that follow this illustration, Nicolas drew sixty-seven mammals, or “terrestrial four-footed animals,” and classified them by their size, the smallest first.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements