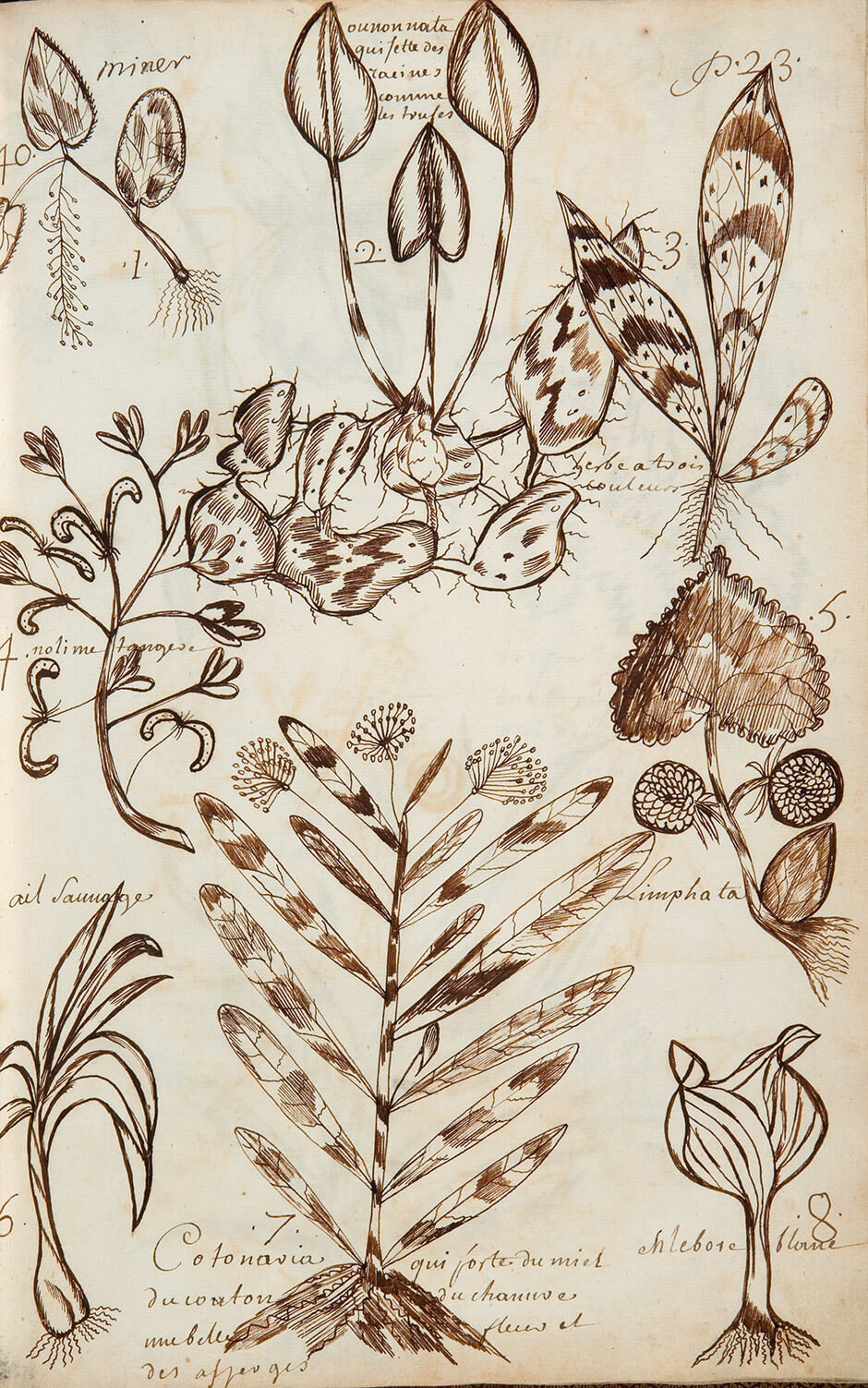

Plants n.d.

Louis Nicolas, Plants, n.d.

Ink on paper, 33.7 x 21.6 cm

Codex Canadensis, page 23

Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Nicolas ordered his drawings in the Codex Canadensis according to a seventeenth-century hierarchy: first humans, then plants, animals, birds, and finally fish. This crowded page, which begins the plant section, contains eight different figures. He captioned number 3, for example, as the “three-colour herb,” number 6 as “wild garlic,” number 7 as the “Cotonaria, which bears honey, cotton, hemp, a beautiful flower, and asparagus,” and number 2 as “ounonnata, which grows roots like truffles.” “Ounonnata,” an Iroquois word, has been identified as the rhizome of Sagittaria latifolia, the broadleaf arrowhead, known in the United States as the wapato or Indian potato. In his rendition, Nicolas chose to highlight its edible tubers.

Botanists have found the “Lymphata” (number 5) difficult to identify because of inaccuracies in the drawing. One expert suggested it is a kind of wild ginger, but others, basing their information on a description in The Natural History, believe it to be a kind of water lily. The name Nicolas used may provide the best clue: in Latin, lymphatus means “watered,” perhaps indicating the plant’s habitat. Identifying plants and animals by habitat was one way in which seventeenth-century natural historians classified them.

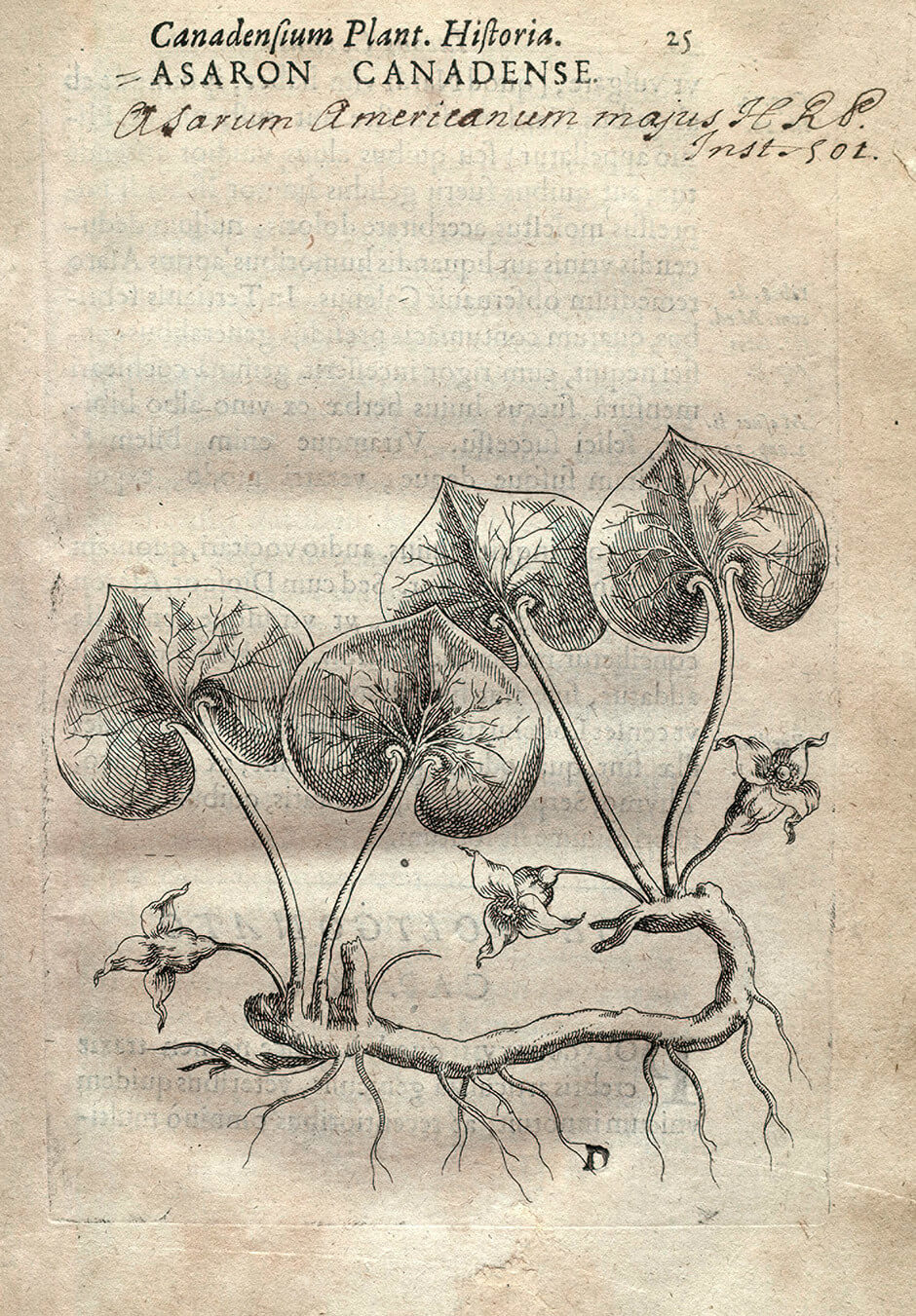

Nicolas was certainly interested in flora: he illustrated eighteen different species on four pages in the Codex. In The Natural History of the New World(Histoire naturelle des Indes occidentales), he describes close to two hundred plants in all—more than any other contemporary writer in New France. Nicolas had observed all the vegetation he drew, unlike botanist Jacques-Philippe Cornut, for example, who never visited North America and in his History of Canadian Plants (Canadensium plantarum historia) (1635) relied on descriptions and specimens provided by other botanists and travellers.

While he worked in New France as a missionary, Nicolas may well have made sketches of these specimens. However, he completed his artworks after he returned to France in 1675. Unlike his drawings of Indigenous chiefs and some of his animals, all the plant images seem to be original to him and not derived from published engravings. He undoubtedly studied the Canadian varieties he found growing in several gardens in Paris and Montpellier, such as the white cedar of Canada in the Jardin des Tuileries, but his distance from his original sources probably explains why some of the plants are poorly represented.

Nicolas lived before Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778), the famous Swedish naturalist who developed modern taxonomy, so he did not depict plants according to the Linnaean principle that emphasizes the sexual organs—the stamens and the pistils. Instead, Nicolas placed emphasis on those parts of the plant most useful to humans—edible, pharmaceutical, or otherwise. In particular, he illustrates the roots, fruits, or flowers. He ordered his drawings according to size—first smaller herbs, then fruit, and finally trees.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements