Kent Monkman’s stylistic approach is the culmination of many years of experimentation. His practice includes a variety of media and disciplines, including performance, painting, sculpture, installation, film, video, and photography. Monkman’s agent provocateur and artistic alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, underpins many of his representations, which present serious narratives in the modes of social satire and burlesque, often using camp and humour to deliver the coup de grâce. As both artist and curator, he has developed a richly collaborative practice that generates groundbreaking interventions in museums and the art world.

From Abstraction to Representation

Early in his artistic career, Monkman pursued Abstract Expressionism, a style that he eventually rejected in favour of more widely legible representational styles of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century paintings. His attention to abstract art was partly a means to distance himself from his work as an illustrator. “I thought the apex of painting was abstract expressionism and that I had to make my individual mark as a painter, whether that was a drip, or a stripe or something else,” he has said. “I inherited the idea that the ultimate goal in painting was to find our own way of making a mark.” Yet Monkman was opposed to the machoism associated with Abstract Expressionist artists such as Jackson Pollock (1912–1956).

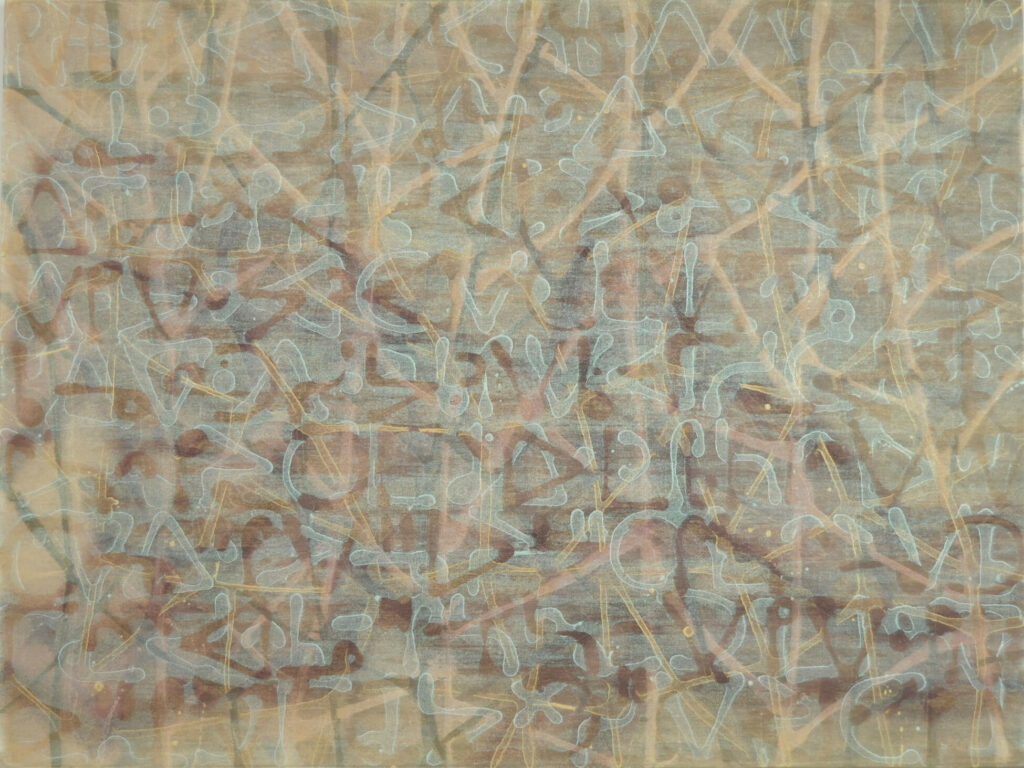

Monkman’s “mark” came when he embarked on a series titled The Prayer Language, 2001, that incorporates syllabics quoted from his parents’ Cree hymn book. His process entailed pouring paint directly on the canvas, moving it around, and then reducing the density by scraping with a squeegee. Partially obscured images of entangled male bodies seem to emerge from behind a transparent veil of paint overlaid with syllabic forms, as can be seen in Softly and Tenderly, 2001.

Yet the visual vocabulary of The Prayer Language failed to adequately address the theme that most engaged him—the impact of colonialism on sexuality. To communicate more clearly, he felt he needed to be more specific: the barely discernible men wrestling had to “come out.” He turned to figurative work, a liberation from what he perceived as the oppressive limits of abstraction.

Rewriting Art History

As he moved away from abstraction, Monkman developed an interest in landscape painting, and several historic works inspired new directions in his art. His earliest research led him to the Group of Seven and their nationalistic renditions of the Canadian wilderness. In the watercolour Superior, 2001, Monkman appropriated the iconic North Shore, Lake Superior, 1926, by Lawren S. Harris (1885–1970) and inserted images of sexually engaged “cowboys and Indians.”

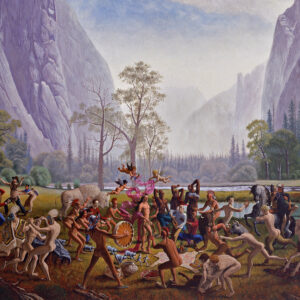

He also became fascinated with the Hudson River School and nineteenth-century painters such as Paul Kane (1810–1871), John Mix Stanley (1814–1872), George Catlin (1796–1872), Thomas Cole (1801–1848), and Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902), who depicted the expanding frontier with sublime mountains and valleys. “I wanted to deal with themes in my own life and my community, like colonization, the impact of Christianity and homophobia,” Monkman has said. “I started looking at landscape painting and North American art history as it was painted by Europeans and how they saw Indigenous people… that narrative needed to be challenged.” To Monkman, the landscapes—with the occasional animal or Indigenous person sprinkled in—were empty stages with huge potential, a perfect avenue for inserting a different story based on his lived experience.

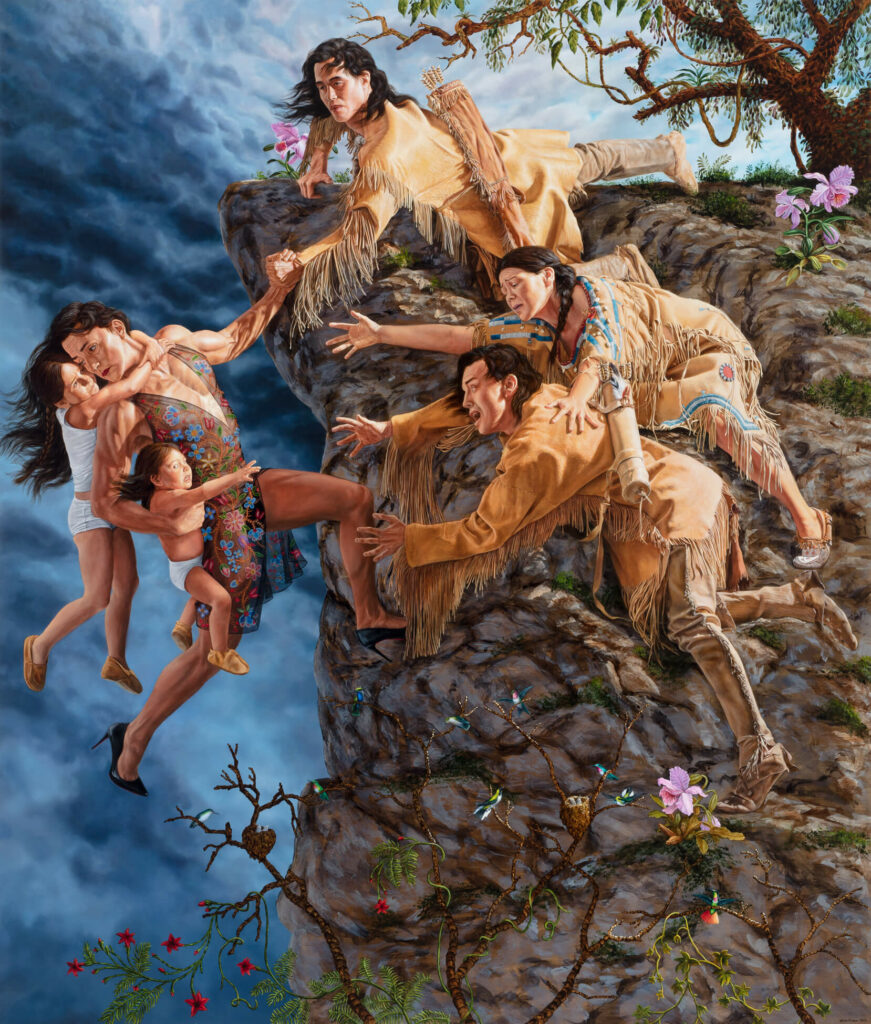

While Monkman’s language of painting is informed by Western art traditions, his art centres on contemporary Indigenous themes. In Ceci n’est pas une pipe, 2001, The Rape of Daniel Boone Junior, 2002, Fort Edmonton, 2003, and Cree Master 1, 2002, Monkman appropriated landscapes and infused them with camp, irony, and kitsch to skewer conventional images of Indigenous cultures. By reproducing the historical compositions, he conceptually reclaims them. In creating such works, he first painted the landscape and scenery, always followed by figures and their stories. With this approach, Monkman devised a method by which he could alter a story, whether from the Bible, classical mythology, the Renaissance, or modern art. Through Miss Chief’s colourful, erotic encounters with European and Western men from centuries past, Monkman reverses power dynamics. In contrast to nineteenth-century depictions of Indigenous peoples as somehow diminished, Miss Chief is strong and confident. As well, her presence counteracts the erasure of Two Spirit people from colonial narratives.

Another tactic Monkman uses is the fusion of time frames, art periods, and locations. In The Fourth of March, 2004, for instance, a dramatic scene unfolds before a lake and mountain vista, where three Métis riflemen are about to open fire on Thomas Scott, an Irish immigrant. The painting quotes from The 3rd of May 1808 in Madrid, or “The Executions,” 1814, by Francisco Goya (1746–1828), which was intended to pay tribute to Spaniards who were executed in 1808 for rising against Napoleon’s armies. In 1870, Métis leader Louis Riel had Scott tried for sedition and condemned to death; the shooting took place at Upper Fort Garry in Manitoba’s Red River Colony, not in an alpine setting as depicted. Monkman takes liberties with his narrative so that an understanding of this history is aptly muddled.

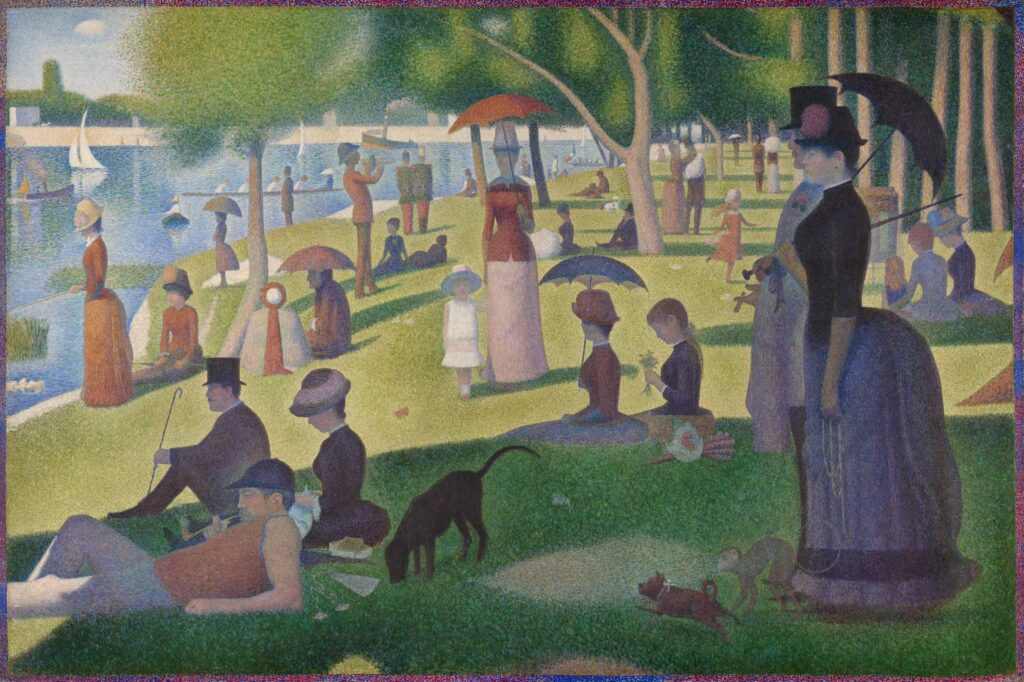

Other visual mash-ups are evident in the paintings God and Man, No Religion, 2012, where a Sasquatch joins a form that resembles a futurist sculpture by Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916); Struggle for Balance, 2013, with angels by Titian (c.1488–1576) flying over street fights and burning cars in Winnipeg’s North End; and Teaching the Lost, 2012, where figurative sculptures by Ossip Zadkine (1890–1967), Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966), Henry Moore (1898–1986), and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) appear in a setting that resembles views by John Constable (1776–1837) or Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665). In Sunday in the Park, 2010, appropriating the monumental A Sunday on La Grande Jatte—1884, 1884/86, by Georges Seurat (1859–1891), Monkman replaced haughty Parisians with half-nude “dandies” who witness Miss Chief painting their portraits as she stands in front of a landscape reminiscent of Bierstadt’s work.

Monkman was also inspired by modernist movements, particularly Cubism with its characteristic flattening of pictorial space and renditions of fragmented figures. To him, the distortion became a metaphor for how Indigenous cultures have been oppressed and how women have been violated in modern art. Through appropriation, Monkman rewrites the past from an Indigenous perspective, all the while asserting the continued relevance of painting.

Film, Video, and Performance

Monkman’s entry into film occurred in 1996 with A Nation is Coming, produced with Gisèle Gordon (b.1964), his collaborator in the film production company Urban Nation. Although he did not address sexuality in the film, he used disease as a metaphor for colonization. Based on the Lakota Ghost Dance and the Anishinaabe seventh fire prophecy, the film uses images of viruses and contamination to reflect on how unfamiliar technologies and sicknesses changed the lives of First Nations. Another film, Future Nation, 2005, addresses the coming out of an Indigenous gay youth in a dystopic Toronto of the future as he finds love during a “megapox” epidemic.

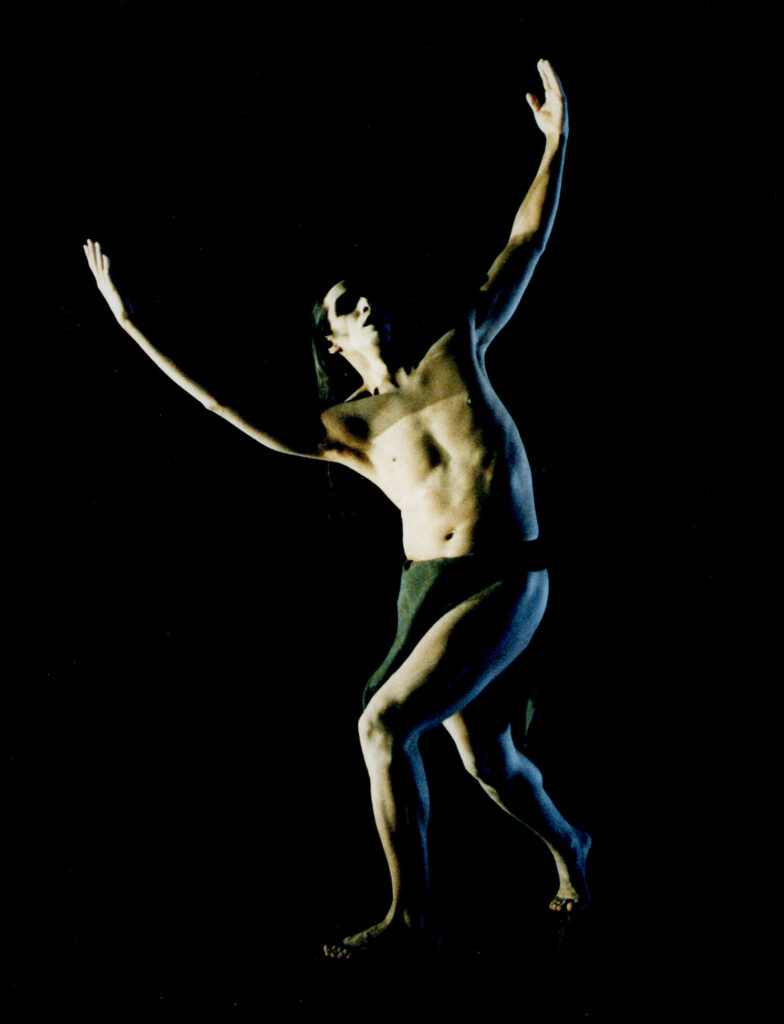

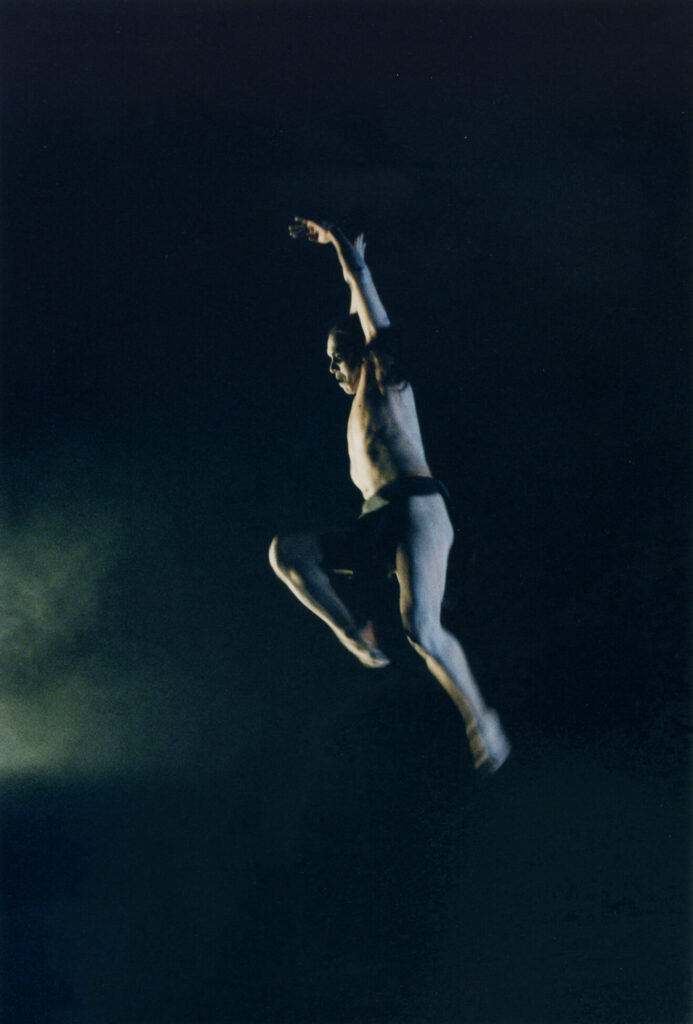

In the exhibition The Triumph of Mischief, 2007, Monkman included a presentation of two silent films projected inside two tipi installations: Group of Seven Inches, 2005, in the Théâtre de Cristal, 2006, and Shooting Geronimo, 2007, inside the Boudoir de Berdashe, 2007. Recalling early stereopticon technology, which photographer-ethnographer Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952) used, Shooting Geronimo is a split-screen “movie within a movie” that takes specific aim at Hollywood’s role in perpetuating Indigenous stereotypes in Westerns. In Monkman’s film, which adopts Curtis’s style of exhorting two perplexed Cree men to perform “The Ghost Dance of the American Indian,” Miss Chief intervenes in her supporting role as a “Lonesome Rider,” orchestrating a breakdance instead. The recollection of the Indigenous tradition of the dance of the berdashe is an important thread in Monkman’s work. In the video installation Dance to the Berdashe, 2008, and the film Dance to Miss Chief, 2010, Monkman reimagined the lost honour dance by resurrecting the Two Spirit figure that has been obscured by colonial history.

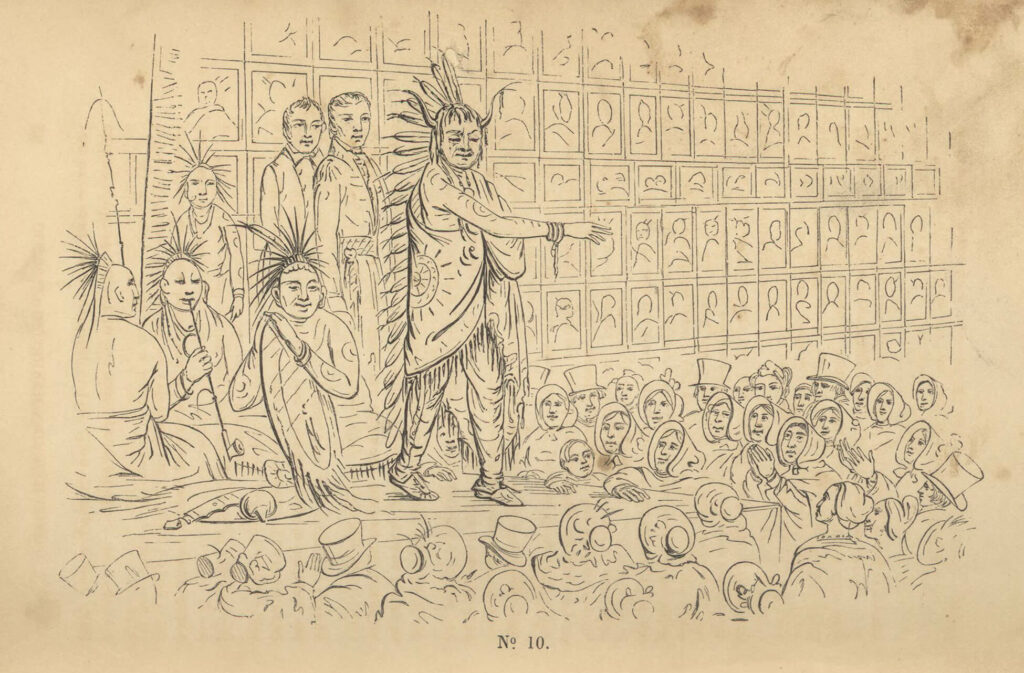

Performance permeates Monkman’s work, informing projects in many media: characters from performances become the subjects of his paintings, painters are depicted within paintings, and paintings are incorporated into installations and documented on video. In Monkman’s words, “you can say and create art in performance language that you can’t in a painting, so it’s really expanded my abilities to communicate with people.” His performances, which he calls “colonial art space interventions,” are modelled after the travelling exhibitions that George Catlin staged in the 1840s, during which he toured paintings, costumes, and tableaux vivants that featured Iowa and Ojibwe actors who would enact scenes and dances conceived by Catlin as “authentic” Indigenous experiences.

Performance allows Monkman to speak in a language that is closer to traditional Indigenous perspectives, and it provides access to a continuation of oral storytelling in a modern context. But Monkman also adapts these practices to create a space for himself and Two Spirit sexuality in the past and present. Miss Chief is the key player and colonial intervener in these works, employing elements of the trickster. A figure in many forms of Indigenous storytelling, the trickster is a mischievous rebel, a jester who challenges authority and is unbound by the rules of time.

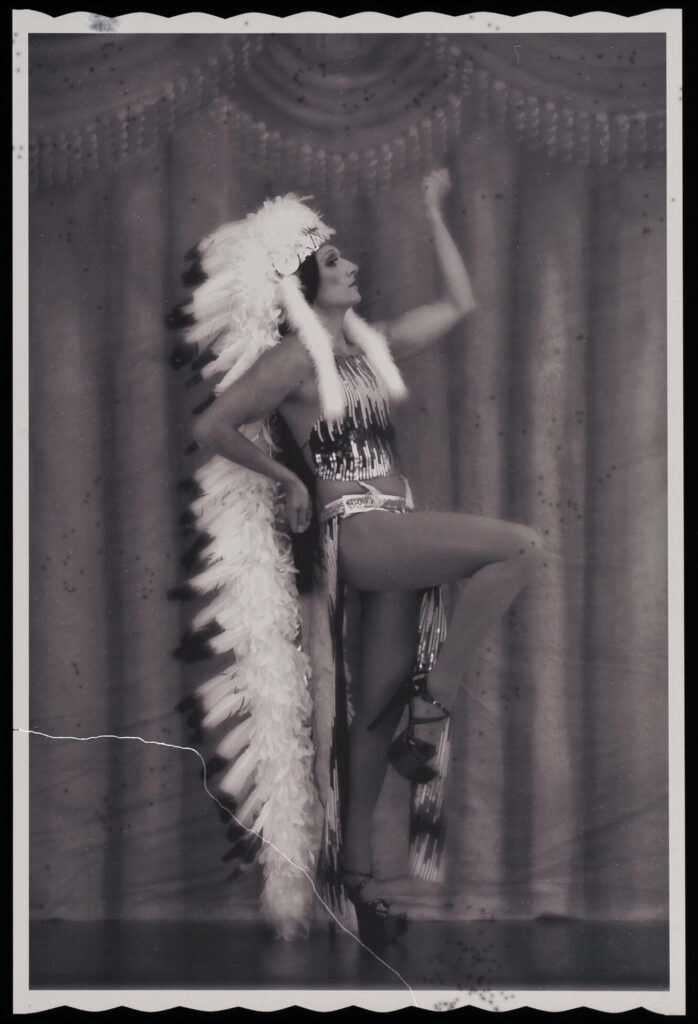

In The Emergence of a Legend, 2006, Miss Chief is imagined as a character in Catlin’s Indian Gallery. The series of five chromogenic prints, produced in collaboration with photographer Christopher Chapman, designer Izzy Camilleri, and makeup artist Jackie Shawn, constitutes studio portraits in which Miss Chief wears various guises. She appears as a warrior, a trapper’s bride (an invention of Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West shows, with reference to Cree brides who married French trappers), a hunter, a burlesque vaudeville star, the 1920s actor Cindy Silverscreen (a character of Monkman’s invention), and a film director. She is also photographed in front of a backdrop of Monument Valley, which is located on the Arizona-Utah border and has been a setting for racist movies such as The Searchers, 1956, starring John Wayne.

In these images, Miss Chief is, in part, a glance back at Molly Spotted Elk, a Penobscot actor and dancer who performed in New York and Paris in the 1920s and 1930s. By playing the starring role in these pastiches, Miss Chief subverts stereotypical pictures of Indigenous peoples, and Monkman questions the work, motivations, and egos of artists such as Catlin and Curtis.

In 2007, Miss Chief appeared in Séance, a performance in which she communicated with the spirits of Catlin, Paul Kane, and painter Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) as part of the Shapeshifters, Time Travellers and Storytellers exhibition held at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto. Monkman was responding to the exclusion of his work from the museum’s First Peoples Gallery for fear that his art would challenge the historical legitimacy of paintings by Kane. His retaliation is shown in Duel after the Masquerade, 2007, in which he portrays a defeated Kane, masquerading as an “Indian” in a buckskin outfit, being held up by a group of white male friends wearing the traditional west coast Nisga’a masks depicted in Kane’s “Medicine Mask Dance,” Northwest Coast Peoples, 1849–56, while Miss Chief walks away victoriously.

In Miss Chief: Justice of the Piece, 2012, Miss Chief dives into a contentious and multi-faceted issue of contemporary North American Indigenous identity. Questions of blood quantum, race, and tribal enrolment are deconstructed as members are inducted into the Nation of Miss Chief. In the performance, a gay white man who married a Cherokee man asks for entry into her nation, since Cherokee nations banned gay marriage in 2004. Implicit is an understanding of identity as a series of performative acts rather than an inborn trait. For Monkman, performance becomes a sovereign act.

Miss Chief is not without precedent in art history. For example, in 1921, Dada artist Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) transformed himself into Rrose Sélavy (a pun on the French phrase “Eros c’est la vie,” or “Eros is life”). Once created, Rrose Sélavy took on a life of her own and lent her signature to works of art.

The idea of identity as performance can also be found in the work of several contemporary Indigenous artists, such as Anishinaabekwe artist Rebecca Belmore (b.1960), who is known for politically conscious and socially aware pieces. In 1991, Kanien’kehaka artist Shelley Niro (b.1954) embarked on a series of photographic self-portraits, Mohawks in Beehives, in which she and her sisters appear done up in beehive hairdos, wearing 1950s fashions and posing like pin-ups. Acclaimed artist James Luna (1950–2018), who was of Payómkawichum, Ipai, and Mexican descent, pushed boundaries in his installations by inserting himself into museum displays in Artifact Piece, 1987/1990, which raised concerns of ethnic identity. Luna relayed that performance and installation offered opportunities like never before for Indigenous artists to express themselves without compromise.

Fashion and Cultural Appropriation

Monkman employs fashion to discuss identity, gender, sexuality, and issues pertaining to racism and colonization. Seeing clothing as a signifier of cultural change, he has used costumes—as early as The Emergence of a Legend, 2006—to highlight how the fashion industry appropriates Indigenous culture.

Initially inspired by pop star diva Cher, Miss Chief’s flamboyant wardrobe consists of feather headdresses, beaded sashes and purses, bone breastplates, a dreamcatcher bra, a signature Louis Vuitton quiver, loincloths, fur jockstraps, Louboutin stiletto heels, platform shoes, fetish boots, and a white mink robe. A faux headdress is the signature item in Miss Chief’s wardrobe, and Monkman wears it as a sign of cultural appropriation. It was seen in Tall Tails, 2007, an installation with music at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Toronto, and was included in the Triumph of Mischief exhibition in 2007. Miss Chief wore three successively larger and more outlandish headdresses during the performance Séance at the Royal Ontario Museum in 2007.

Fashion has been critical to Miss Chief’s performances. At a reception at The Drake Hotel in Toronto in April 2005, Monkman donned four costumes over the course of the evening and made dramatic entrances into the lounge area of the bar. A variety of Miss Chief’s adopted personas appeared: Cher’s glamorous Bob Mackie look, with the floor length headdress; Mrs. Custer from Monkman’s remake of the William S. Jewett (1821–1873) painting The Promised Land — The Grayson Family, 1850; Miss Tippy Canoe, a trapper’s bride in a fur bikini; and Warrior Princess, decked out in “Oka-chic.” The latter costume, designed by Monkman, consisted of a floor-length sheath skirt in grey and black camouflage, slit to the top and paired with a scarlet, sequined, stretch tank top emblazoned with a Mohawk Warrior flag. The outfit echoed the persona of the fictional TV character Xena on Xena: Warrior Princess, a lesbian pop-culture icon of the 1990s. It also referenced the Oka Crisis, 1990, when the people of Kanehsatà:ke fought the governments of Oka, Quebec, and Canada to protect their traditional lands.

Miss Tippy Canoe’s outfit was connected to the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe, in which General William Henry Harrison, charged with securing newly acquired Indiana territories, defeated Tecumseh, who was building a First Nation. The bustled wedding gown of bug screen mesh that she wore, which was embroidered with tiny wooden canoes, was designed and created by fellow Anishinaabe/Ojibwe artist Bonnie Devine (b.1952) and Paul Gardner. Underneath, Miss Chief wore a fur jockstrap that was fashioned from the coonskin cap of late Globe and Mail film and art critic Jay Scott. The costumes were displayed in the hotel lobby, along with several paintings, for the duration of the exhibition.

On September 8, 2017, Monkman gave a performance in connection with the exhibition Love Is Love: Wedding Bliss for All à la Jean Paul Gaultier at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. The show included a white feathered headdress with a wedding gown from Gaultier’s 2012–13 haute couture collection. In the context of the debate over cultural appropriation, Monkman felt it demanded a response. To Plains First Nations, the hallowed headdress, or war bonnet, has spiritual significance. It is not something simply worn; it is earned, one feather at a time, with each gifted in gratitude for honourable deeds over the course of one’s life. To be presented with an eagle feather is a sign of great respect. In his live performance, Monkman, through Miss Chief, reclaimed the white feathered headdress by wearing it and “marrying” Gaultier, one of the fashion world’s most legendary iconoclasts. Through the symbolic union, both artists came together to challenge ideas of cultural appropriation and gain deeper understanding.

The act of cultural appropriation is significant in the fashion industry, which is often guilty of the explicit use of Indigenous pattern traditions in commercial clothing design without consideration of the meaning behind them. Forever 21, Urban Outfitters, and other fast fashion brands have used Indigenous aesthetics as “inspiration,” sometimes leading to horrible ends. The majority of these labels have had little to no collaboration with members of Indigenous communities or with Indigenous fashion designers. One rare exception was the collaboration between the House of Valentino and Métis artist Christi Belcourt (b.1966). Italian designer Valentino transferred images from Belcourt’s painting Water Song, 2010–11, onto clothing for his 2016 Resort collection. Belcourt’s work inspired Miss Chief’s dress in Monkman’s work The Deluge, 2019.

The Museum Diorama

Through dioramas, Monkman addresses museum conventions of representation, a critical theme in his work. Dioramas were introduced into North American natural history museums at the end of the 1880s. As three-dimensional tableaux, they presented a strange mixture of reality and fiction: they usually contained human figures or taxidermy creatures, positioned in pseudo-naturalist environments and set against panoramic backdrops painted in trompe l’oeil fashion.

The ethnographic dioramas that Monkman encountered as a child at the Manitoba Museum in Winnipeg employed the myth that Indigenous peoples were a “vanishing race,” a belief that was widespread in the field of anthropology. It was based on a dramatic demographic decline in Indigenous populations—quite real at the end of the nineteenth century—and fuelled by the idea that the “noble Indian” could not resist the assault of modern civilization and would soon be completely assimilated by it. Several historic artists perpetuated this narrative, which Monkman responded to in paintings such as The Impending Storm, 2004.

While touring the Native American wing of the American Museum of Natural History in New York in 2008, Monkman noticed some troubling representational practices. The mannequins of Indigenous bodies at the museum were not only grouped in with animals but also shared identical stereotypical features. “You walk through the museum and you see signage for primates this way and Native people this way, and it’s a very disturbing experience. In the Native American section, you see one face used to standardize all of Indigenous North America, regardless of nation, sex, or gender,” he noted. Soon after this visit, Monkman began placing a cast of his head on all figure sculptures in his dioramic installations.

The museum diorama’s pre-film aesthetic, with its combination of painting, sculpture, photography, and theatre, fascinates Monkman, and in revisiting it, he critiques it. The installation The Atelier, 2011, offers a glimpse into his employment of the idiom. A space is transformed into the corner of an artist’s studio, complete with furniture, studies, drawings, reference materials, and etchings. It resembles a museum display, with antique furniture and vintage wallpaper that captures the historical flavour of the nineteenth century.

Monkman plays with anachronisms, fact, and fiction, and complicates ideas of what is authentic and historically correct. He also critiques nineteenth-century Western novels that show a fascination with Indigenous cultures; the texts enticed people to dress up and play “Indian” during summer vacations. Dance to Miss Chief, 2010, which was screened as part of The Atelier exhibition, uses the idiom of the music video to remix footage from German Westerns and Monkman’s seminal multi-channel video installation Dance to the Berdashe, 2008.

Miss Chief has also appeared in other settings. In the full-scale diorama The Collapsing of Time and Space in an Ever Expanding Universe, 2011, Monkman recreated a Parisian apartment lodging Miss Chief with various stuffed animals, including a beaver, coyote, and raven. She is presented as an aging diva alone with her faithful animal companions, listening to her one hit record and longing for lost youth.

The Big Four, 2012, was a diorama produced for the 100th anniversary of the Calgary Stampede and commissioned by the Glenbow Museum. The numerical theme was inspired by the Stampede’s founder and four financial backers, who had insisted that the local First Nations be included in the first Stampede in 1912 but had to exert considerable political influence to make it happen, as Indigenous communities were incarcerated on their reserves. Using this historical separation as a starting point, Monkman’s The Big Four is a playful yet serious reflection on imprisonment, mobility, and freedom, and also a critique on the representation of First Nations people in institutions like the Glenbow Museum.

Four vehicles (a minivan, a pickup truck, and two sedans) were situated in the gallery space, each with its own vignette, depicting some aspect of First Nations life and cheekily taking on the typical scene found in museum dioramas. In the minivan, a woman sits in the back selling clothing and beads; in the pickup truck, a cowboy loads in his gear, with sparkly jewellery slipping out from under his shirt; in one sedan, a spectator watches TV in the trunk; and in another, a troublemaker is behind the wheel and fleeing with few possessions. Each character bears Monkman’s face, a direct critique of the tendency by museums to feature one face for many cultures and different genders. As has been noted by Deena Rymhs, the use of the four automobiles “explores Indigenous people’s confinement in various settings—the reserve, the museum, the administrative borders of the state, and outdoor Wild-West-inspired exhibitions that sidelined Indigenous people to stock anachronistic figurations.“ Monkman also used the cars as museum cases—or vitrines, in a way—to show objects from the museum’s collection.

The Rise and Fall of Civilization, 2015, and Bête Noir, 2014, also make forays into the diorama idiom. In the former, a realistic cliff, models of buffalo, and a mannequin of Miss Chief come together as entities frozen in time. Some buffalo appear lifelike at the top of the cliff while others are abstracted, resembling line drawings or pictographs and Cubist forms reminiscent of Pablo Picasso’s works. The diorama appears to flow from prehistoric times to the present day, functioning as a metaphor for the disappearance of buffalo by European settlers. The flattening of pictorial space in Monkman’s work runs concurrently with the suppression of Indigenous cultures within the reservation system and residential schools. In Bête Noir, the famous and inaccurate painting The Last of the Buffalo, 1888, by Albert Bierstadt, which depicts an Indigenous man on horseback battling a buffalo, sets the backdrop. Here, Monkman turns the tables by presenting the buffalo as living and thriving, while a flattened, Picasso-style bull made from pieces of real cowhide is situated in the foreground.

Incorporating Museum Objects

Monkman has often incorporated objects and paintings from the permanent collections of museums in his art. By presenting these pieces in revisionist contexts, Monkman works toward decolonizing the museum. According to Toronto-based activist Syed Hussan, decolonization is “a dramatic reimagining of relationships with land, people and the state.” It involves an unlearning of existing power structures—for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. In museums that have both questionable collecting practices around Indigenous objects and artworks by settler artists that portray Indigenous peoples, the act of unlearning and revision is a necessary action. It takes the form of rejecting, reviewing, and revising practices inherited from a colonizing regime in order to move forward. This practice is pronounced in exhibitions such as Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience, 2017.

In preparation for the show, Monkman and his team visited museums across Canada, researching artifacts to display with his paintings in the different sections of the exhibition, which he called chapters. For example, “Chapter III: Wards of the State/the Indian Problem” included The Subjugation of Truth, 2016, which depicts an imagined scene where pîhtokahanapiwiyin (Chief Poundmaker) and mistahimaskwa (Big Bear) sign a treaty with Prime Minister John A. Macdonald. It was accompanied by a display of Poundmaker’s actual moccasins, borrowed from the Canadian Museum of History, Gatineau. Macdonald also appeared in the painting A Country Wife, 2016, this time with Miss Chief.

In “Chapter IV: Starvation,” a long dining table is set for a celebratory meal. At one end, symbols of nation building appear on the dishes: a portrait of General Wolfe, and an image of a beaver, a railroad, and the Fathers of Confederation. At the other end, as the surface of the table changes into rough boards, there is less food, a spilled glass of wine, and a plate with an image of Queen Elizabeth II atop a yellowed, tattered-lace table runner. Monkman’s Starvation Plates, 2017, which are decorated with archival-photograph reproductions of mounds of buffalo bones, are set amid the scattered bones of small animals. By the early 1880s, with buffalo on the brink of extinction and food scarce, First Nations communities on the Plains were starving, and in order to be fed, the Canadian government, led by Sir John A. Macdonald, forced them to live on reserves; desperate to feed their families, many First Nations women were forced into prostitution and were abused by local government officials.

In “Chapter VI: Incarceration,” Monkman included a pair of handcuffs and a pair of leg irons from the collection of the Museum of Vancouver, objects that were used on Louie Sam, a Stó:lō teen in British Columbia who was lynched by an American mob while awaiting trial in 1884. Photographs of Poundmaker and Big Bear and Riel Rebellion prisoners under arrest, borrowed from the Glenbow Museum, flanked the objects. Through juxtapositions like these, the exhibition emphasized the dark themes of colonialism while also sending a message of Indigenous resilience.

Collaboration and the Studio Process

As Monkman’s career has catapulted onto an international stage and the demand for his work has increased, his studio practice has adapted. It now operates like a Renaissance atelier, where a team of apprentices assists a master artist. Historically, when works were commissioned, apprentices would often complete a large portion of the painting, leaving the difficult details to the master. When Monkman worked alone, his plans began with a sketch, followed by a small painting. The “image study” served as a reference for a bigger canvas, where Monkman would fill in gaps and improvise along the way.

Monkman’s compositions are realized through collaboration, a process that he first began when working with Gisèle Gordon in 1996. Describing the development of Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience, where he was both artist and curator, Monkman noted, “the images came first, as did the structure of the exhibition and curation of the objects. Miss Chief’s narrative came at the end. Gisèle Gordon wrote them and was able to get inside my brain and unpack all the layers and intentions behind the work.” Monkman acknowledges that a vital part of his work is the involvement of makeup artists, fashion designers, and filmmakers.

In 2006, with numerous speaking engagements compounded by a busy exhibition schedule, Monkman moved from the traditional method of working alone to working with a team who paint under his direction. He begins with making sketches, then enlists live models and actors who pose for specific works; for the paintings Welcoming the Newcomers and Resurgence of the People, both 2019, he worked with dozens of different people. The enactments are photographed, then projected onto canvas. The team paints sections of the canvas until the final stage, when Monkman completes it alone.

Monkman’s first project to employ real actors was Death of the Virgin (after Caravaggio), 2016, which draws on Death of the Virgin, c.1601–6, by Caravaggio (1571–1610) but replaces the Virgin Mary with a young Indigenous woman in a contemporary setting. She lies in a hospital bed surrounded by loved ones who drum, smudge, and pray, and the work is a sharp commentary on the issue of murdered and missing Indigenous women.

Similarly, in They Are Warriors, 2017, Indigenous and white models posed for a tableau depicting a scrummage between Indigenous “warriors” and white police, a scene quite common in today’s media. Monkman collected recent news images of the arrests of Indigenous protesters at Standing Rock Indian Reservation in North and South Dakota, who were attempting to stop the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, as well as images of battle scenes from art historical sources. Like Death of the Virgin (after Caravaggio), the painting possesses a hyperrealist style that heightens the emotions and amplifies the reality of the issues affecting Indigenous peoples.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements