By exposing the complexities of historic and contemporary Indigenous experiences, Kent Monkman has raised awareness of critical challenges facing communities today. He has brought together explorations of Two Spirit identity and sexuality with a commitment to investigating treaties and recognizing lived realities for Indigenous peoples in cities and on reserves, and he has developed groundbreaking projects to decolonize museums across Turtle Island. Through deeply personal and compelling work, he has provoked transformative conversations about identity and history in Canada.

Reclaiming Two Spirit Identity

When he created his alter ego Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, Monkman set out to challenge dominant Western discourses of sexuality, power, knowledge, and gender, and the persisting misrepresentations of Indigenous peoples by Europeans. Prior to colonization, many First Nations honoured those who were Two Spirit or had other non-binary genders and sexualities as sacred members of society. The term “Two Spirit” is derived from niizh manidoowag, an Anishinaabemowin term. It is used to express the existence of “a third gender” that is both a spiritual and physical state of being. Early Christian European settlers were openly hostile toward these individuals because they did not fit into accepted colonial belief systems. Some Two Spirit people were referred to as “berdache,” a derogatory name given to feminine males by French explorers and anthropologists.

In bringing Miss Chief to life, in works ranging from paintings like Study for Artist and Model, 2003, to films such as Dance to Miss Chief, 2010, Monkman uses his own sexuality to support his goal of deconstructing imperial historical constructs. “I got a lot of empowerment about my own identity and my own sexuality the more I learned about Two Spirit sexuality, the fact that Indigenous cultures had a place for Two Spirit people.” Monkman mines complex, difficult, and continuously evolving cultural connections in his work, engaging with histories that have potent racist and homophobic elements, and embodying the Two Spirit presence through Miss Chief’s appearances.

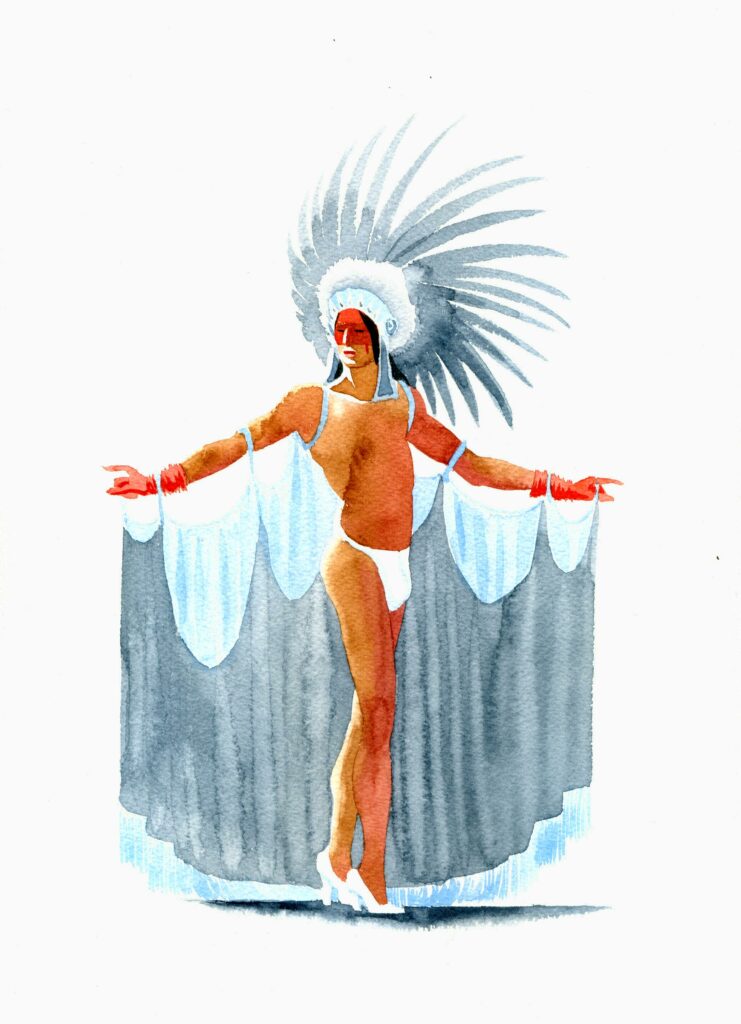

Monkman often employs irony to confront those early artists and explorers who expressed fascination for Indigenous peoples, even as they exploited them. In 2008 he created a group of watercolours (including Faint Heart 27,148 and Faint Heart 7,558) responding to George Catlin (1796–1872) and his encounters with “dandies,” a term Catlin used in reference to gender-variant people in Indigenous nations such as the Mandan (now North Dakota). Also called “faint hearts,” the “dandies” vexed Catlin—despite disparaging them in his journals as being feminine, he harboured a secret fascination with their appearances and fancy outfits. He wrote about them “pluming themselves with swan’s down and quill of ducks and plaits of sweet-scented grass… looking pretty and ornamental.” Catlin began a portrait of one of these men that reportedly caused a ruckus, since they were not considered as high ranking as chiefs and therefore were not appropriate subjects. He ultimately abandoned the painting, having only rendered the figure in preliminary outline.

In another series, Monkman repopulates Catlin’s scenes of warrior Mandan chiefs with “dandies.” Eagle’s Ribs with Tinselled Buck No. 6,932, 2008, and Old Bear with Tinselled Buck No. 10,601, 2008, depict, respectively, a warrior and a shaman. Each figure is paired with a chalky, ghostlike sketch of a lounging “dandy.” The title numbers, arbitrarily assigned by Monkman, refer to Catlin’s form of documentation. The works are reminiscent of Catlin’s renditions of stoic, romanticized, and colourfully dressed Indigenous men. In Monkman’s versions, however, the ghostly images command more attention than those in front, emphasizing the erasure of non-heteronormative forms of Indigenous sexuality and gender by colonial artists. Writer Mark Kingwell remarks that it is “only through the processes of virtual auditing that Monkman was able to rescue the dandy from obscurity.”

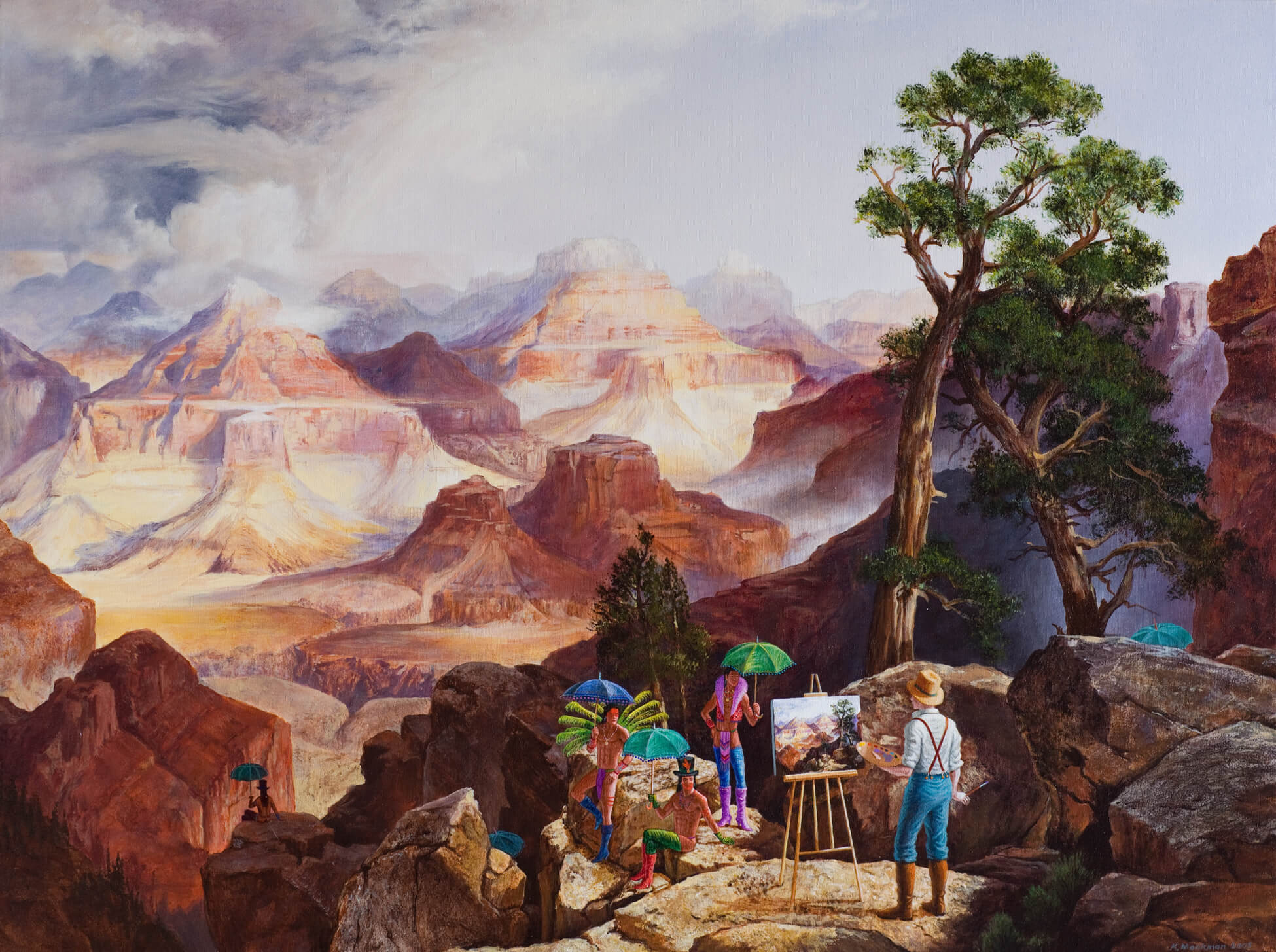

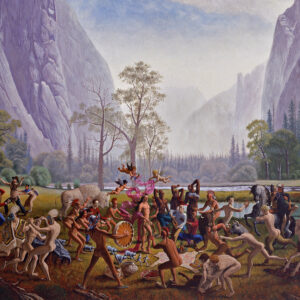

“Dandies” also make an appearance in Monkman’s painting Clouds in the Canyon, 2008. Resembling a typical nineteenth-century painting, the work depicts an artist with his back turned, painting the Grand Canyon and seemingly unaware of the vibrantly clothed “dandies” lounging in the landscape around him. But they are difficult to miss, clad as they are in vibrant colours, wearing lavender boots, blue leggings, pink and purple loincloths, and sporting green parasols. For Monkman, the “dandies” are reoccupying colonized territories, and by inserting them into paintings, he returns power to Two Spirit peoples.

Decolonizing the Museum

As colonial institutions, museums have constructed, circulated, and reinforced narratives that oppress Indigenous people and perpetuate systemic racism. Collection, interpretation, and display practices are interconnected with processes of plunder and subjugation. Museums have accepted donations of stolen art and objects, and even human remains. They have represented Indigenous peoples as if frozen in time and obscured vast cultural and linguistic diversity. Yet when institutions invite Indigenous artists and curators to intervene critically within them, museums can be transformed into important spaces for Indigenous counter-narratives and self-representation—both of which have been significant for Monkman.

Curator and art historian Ruth B. Phillips notes that in the late twentieth century, some Canadian museums began to shift their practices in relation to Indigenous peoples. Many were embracing multiculturalism, becoming more pluralistic, and finding it increasingly difficult to ignore Indigenous communities’ demands for justice. The beginnings of museum transformation occurred within the spaces created by new constructions of nationhood and Indigenous activism against controversial exhibitions. Still, Indigenous work existing in non-Indigenous spaces is complicated by issues of racism, appropriation, and neocolonialism. Decolonization entails a dramatic reimagining of relationships with land and people and demands an “unlearning” of existing power structures for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

Monkman recognizes that creating truth-telling spaces within museums can upend colonial narratives and transform identities and relationships. His insistent research into permanent collections is a strategic move to get inside the works of art and to revisit and correct history. It is an approach that has informed several bodies of his work. For instance, prior to the Triumph of Mischief exhibition opening at the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 2008, Monkman gathered source material from three iconic works in the museum’s permanent collection: Femmes de Caughnawaga, 1924, a bronze by Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté (1869–1937); The Dakota Boat, c.1875, a painting by Washington Frank Lynn (1827–1906); and A Halfcast with His Wife and Child, c.1825, a watercolour by Peter Rindisbacher (1806–1834). Visual quotations from these works are seen in Monkman’s painting Woe to Those Who Remember From Whence They Came, 2008, which retells the story of his people leaving their ancestral land. A prairie vista overlooking historic Fort Garry (today the location of central Winnipeg) sets the stage as the site where Treaty No. 1 was signed by the Ojibwe and Swampy Cree of Manitoba and the Crown. In the centre of the canvas, walking behind a Métis family, is the apparitional figure of Miss Chief. As she is commanded to leave, she glances woefully back to her homeland, and this act of disobedience results in her being transformed into a pillar of salt like Lot’s wife in the Bible.

Monkman’s appropriation of historical paintings with the integration of museum collection objects sets a new paradigm for the decolonization of these spaces. His radical method was evident in the work produced for the Great Hall at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the epitome of an “encyclopedic” museum that is thoroughly Western in its development. In the installation mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People), two paintings, Welcoming the Newcomers and Resurgence of the People, both 2019, are heavily populated with identifiable references to European and North American artworks in the museum’s collection. They make particular reference to pieces that perpetuate the myth of a “dying race” through their depictions of Indigenous subjects.

An earlier project of Monkman’s, Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience, which was on view at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto in 2017, was a seminal decolonizing venture. Launching it the same year that Canada was marking its sesquicentennial, Monkman deployed Miss Chief Eagle Testickle to disrupt the celebration. In paintings, installations, and texts, she travelled back in time before Confederation to trample on foundational myths and tell the dark, shameful story of legislated genocide. Spanning multiple rooms, Monkman’s exhibition began with a portrayal of Indigenous peoples as equal partners in the fur trade, and then moved the narrative through decades of colonization. The exhibition intentionally challenged and subverted the very space it occupied—the colonial power of the museum itself. For instance, with Nativity Scene, 2017, Monkman offers a contemporary reinvention of the museum diorama, one that highlights the poor housing on reserves. Through works like this one, Shame and Prejudice overthrew museological conventions to foreground Indigenous resilience within structures of ongoing colonialism.

Monkman tells the story from the point of view of the colonized, and through his provocative pairings of paintings with museum objects, he upends representational practices that are common in museum displays. Through Miss Chief, he exposes and ridicules structures of patriarchy, racism, and colonialism. His paintings create a place in Canadian art history for First Nations, with an emphasis on those who have been most subjected to colonial violence: mothers and their stolen children, missing and murdered women and girls, Two Spirit people, and incarcerated individuals. By virtue of their presence in the space, viewers become implicated in the retelling. As they are seduced by Monkman’s tableaux and scenarios, a startling decolonizing provocation occurs.

Urbanization, Indigenous Identity, and Modern Art

While much of Monkman’s work from 2004 onward focused on subverting historical narratives within natural landscapes, in 2014 he transported Miss Chief to an urban setting. His aim was to expose how Indigenous cultures have been displaced by colonization and to counter dominant stereotypes of Indigenous peoples as authentic only if they live in remote areas or on reserves. The circumstances of many contemporary Indigenous peoples are exposed in his Urban Res series, 2013–16, which stresses displacement. Monkman noted, “I wanted to re-stage some of these scenes in urban environments, because a lot of Indigenous people live in cities. In Canada, more than half are living in cities. And a lot of urban environments are places where Native people once inhabited. This ties back to some of the themes in my current work—this amnesia in the face of modernity.”

Winnipeg’s North End inspired the Urban Res body of work. “What I love about Winnipeg is that this is my territory,” Monkman said. “I feel very much like I belong here. My view of the world, everything that I think about, is shaped by being from here…places like Winnipeg were gathering places for Indigenous people, so this is Indigenous territory as much as any other place. And yet people live in substandard conditions and there’s lateral violence here and in this part of the city there’s a visible difference between how Indigenous people live and how non-Indigenous people live.” The North End neighbourhood is home to the largest population of Indigenous residents in the country and is one of Canada’s lowest income centres.

For the series, Monkman revisited sites in Winnipeg that provided inspiration for paintings such as Le Petit déjeuner sur l’herbe, 2014, which is named after a work by French artist Édouard Manet (1832–1883) and depicts women resembling the sex workers in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) in front of an inexpensive hotel. Similarly, in The Deposition, 2014, Miss Chief cradles a female figure quoted from Picasso’s Guernica, 1937, while she herself is caught by a group of young Indigenous men as she collapses.

In Death of the Female, 2014, Monkman juxtaposes modern and historical imagery through the intersection of European Christian symbols and traditional Indigenous cultural signifiers. At the corner of Chambers Street and Alexander Avenue in Winnipeg, four young Indigenous men attend to another woman who appears to be a victim of some sort of assault, her naked form twisted and in distress. With clear allusions to Picasso in his rendering of Cubist female figures, Monkman does not limit the iconography in Death of the Female to geography, religion, or Indigenous symbolism. He has described Picasso’s approach as “butchering the female nude,” and for him it became “a way of speaking about and representing the violence being perpetrated against Indigenous women.”

One of the men in Death of the Female is traditionally dressed, wearing a buffalo horn headdress with an eagle feather bustle that reaches down to the ground, similar to one in Penn’s Treaty with the Indians, 1771–72, by Benjamin West (1738–1820). However, in contrast, the figure in Monkman’s work is also wearing jeans and white Adidas sneakers. Countering stereotypical representations of Indigenous men in history, Monkman reveals their present-day reality. Paying close attention to detail, he exposes dichotomies contemporary Indigenous men contend with, such as having long versus short hair, or religious versus traditional tattoos. Despite their conflicting appearances, the men in the painting all exhibit concern for the woman. They represent binary stereotypes of Indigenous peoples today: those who have assimilated and lost the traditional teachings and language, and those who have not assimilated and practise traditional ceremonies.

In Monkman’s Bad Medicine, 2014, angels face off against bear spirits, revealing how Indigenous spirits move through urban environments amid drug use and violence. Cash for Souls, 2016—set outside an actual pawnshop on Main Street, located a short drive from the Manitoba Museum in Winnipeg—portrays a realistically rendered street fight between guards, transgender women, and prisoners in orange jumpsuits. The work parodies The Abduction of the Sabine Women, 1633–34, by Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665). The themes of displacement, violence, and incarceration permeate the series through this remixing of history.

Monkman also depicts the city as a prison. The installation Minimalism, 2017, in which a mannequin of an Indigenous inmate is held in a shockingly minimal space that echoes the modernist sculptures of Donald Judd (1928–1994), is also a metaphor for the reduction of First Nations territories. While Monkman aggressively questions the language of modernism and its flaws, he also points out that Indigenous peoples, especially women, are trapped in cycles of violence and alienation. In Struggle for Balance, 2013, female casualties and mourners are caught up in a maelstrom of rioting and gun violence. The urban cataclysm includes humans, animals, and fantastical creatures drawn from the history of painting. They appear as victims and aggressors, fatalities and survivors. This representation of Indigenous culture as current, authentic, and active creates a critical commentary that exposes the aftermath of colonization.

Honouring Treaties

The loss of ancestral territory is a constant issue for generations of First Nations, as colonization has alienated Indigenous peoples from their land and homes. In several projects, Monkman has drawn attention to how Indigenous peoples and lands share a common fate as victims of colonial violence. For instance, his site-specific installation at the Gardiner Museum, The Rise and Fall of Civilization, 2015, revealed the stark contrast of Indigenous sustainable hunting practices with the catastrophic slaughter brought about by colonialism by juxtaposing the traditional buffalo hunt with ceramic shards alluding to the bones of the animals killed by settlers and the china made from the skeletal remains.

Monkman’s subversive appropriation of nineteenth-century landscapes, such as the works of Thomas Cole (1801–1848) and Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902), is a means to address the colonial desire for territorial expansion. He doesn’t merely reproduce these empty landscapes that erased the presence of Indigenous peoples; as critic June Scudeler notes, he shows how these landscapes are not “neutral territory but riddled with the ideologies, desires and sensibilities of their makers.” His are landscapes of the trauma of colonization, cultural compression, spatial dislocation, and historical amnesia.

In the multimedia work My Treaty is With the Crown, 2011, which was exhibited at the Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery in Montreal, Monkman took specific aim at the issue of sovereignty. His intervention as a curator, history painter, and Miss Chief evoked two significant events in Canadian history: the Battle of the Plains of Abraham on September 13, 1759, where the British victory ended the French empire in North America, and the Prince of Wales’s visit to Canada in 1860. For the project, Monkman borrowed objects from the McCord Museum, Montreal, and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. In a room that looked back to the pivotal battle, historical objects represented the demise of General Montcalm, portrayed in a French etching from 1760 and a French Canadian painting from 1903, and General Wolfe, pictured on a nineteenth-century English painted ceramic. Monkman also installed tents—one decorated with fleurs-de-lis and the other with a Union Jack, representing the French and British, respectively. Inside them were two paintings depicting Miss Chief entering the battlefield. In scenes inspired by the Biblical character Delilah, who cut off Samson’s hair to take away his strength, Miss Chief is shown cutting the generals’ hair, signalling their impending deaths and making her the author of that moment in Canadian history and a disrupter of sovereign power.

With the large-scale multi-figure history painting My Treaty is With the Crown, 2011, Monkman staged Miss Chief meeting the Prince of Wales on the banks overlooking the St. Lawrence River and the Victoria Bridge. Miss Chief enacts an ancient ritual of washing the feet of the visitor, echoing the story of Mary Magdalene washing and anointing Christ’s feet. In sharp contrast to the Biblical narrative, Monkman’s accompanying video, Mary, 2011, takes on a darker tone. Miss Chief, in a short, sequined red dress and knee-high red boots, hair billowing behind her, kneels and begins lovingly stroking the feet of the actor portraying the Prince of Wales. As tears flow from her eyes, black mascara drips onto his feet. The text in the video clip reads: “We had an agreement / we agreed to share not surrender/how could you break your promise.” Hearkening back to the confines of the Indian Act, the interpretation of treaties differs between Miss Chief and the Prince of Wales.

Where First Nations saw treaties as agreements of kinship and shared obligations and responsibilities, European settlers interpreted treaties as transfers of ownership. Mary is about the breaking of treaties—something Monkman takes personally. One of the largest unceded territories was the ancestral land of his family in St. Peters, Manitoba. Monkman’s connection to the dispossession of this land is deeply felt, because his great-grandmother spent the first ten years of her life in turmoil as her family was forcibly relocated three times. “Because I had a relationship with this amazing person for the first ten years of my life, I feel connected to this history in a personal way,” Monkman has said. The loss of ancestral land also plays out in Lot’s Wife, 2012, and Woe to Those Who Remember From Whence They Came, 2008.

Monkman has also looked back to earlier treaties. At the centre of the 2018 exhibition Beauty and the Beasts at the Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris was Miss Chief’s Wet Dream, 2018, a monumental canvas that took inspiration from two iconic French paintings: The Raft of the Medusa, 1818–19, by Théodore Géricault (1791–1824), and Liberty Leading the People, 1830, by Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863). Two vessels are shown: a canoe carrying Indigenous travellers, and a boat with European occupants. The content for the work was taken from the Two Row Wampum, also known as Teiohate Kaswenta, of 1613, which was an agreement between the Haudenosaunee people and Dutch settlers. Wampum belts made as symbolic representations of that treaty contained two rows of purple beads on a white background with the rows representing equal parties, each travelling in their own canoe, who will not interrupt each other’s paths.

Impact

The critical issues that Monkman addresses in his work include racism, the erasure of Two Spirit individuals, Indigenous sovereignty, the revision of historical representations of Indigenous peoples, and the process of decolonization. His intent is to accentuate Indigenous resilience and the survival and vibrancy of Indigenous ways of knowing—specifically Cree knowledge. With many powerful paintings that look back to Old Masters, such as Cash for Souls, 2016, and Resurgence of the People, 2019, Monkman is often situated within art historical criticism as rewriting the Western art historical canon—but it is crucial to note that he does so with a Swampy Cree holistic worldview. Central to his approach toward restitution is the Cree concept of good relations that leads to strong and stable nations: miyo-wîcêhtowin.

According to Cree curator, critic, and art historian Richard William Hill, Monkman’s art marks “a shift in the discourse around Indigenous representation. He is certainly not the first Indigenous performer or artist to address the history of colonial ideology as visualized in the arts, [but] he is the first to explicitly recognize, respond to, and manipulate the operations of desire at work in those representations… [he is] able to intervene in a different and perhaps ultimately more subversive way.”

Monkman has been hard at work for years, provoking conversation and engagement with Indigenous issues in a deeply personal way and with a curious juxtaposition of horror and beauty that destabilizes as much as it compels. As his work gets shown across Turtle Island, momentous waves of change in museums and other colonial institutions are occurring. Through revisiting and reinventing iconic moments in Canadian consciousness, he creates work that enters the canon in a new way, reflecting other truths and revealing other experiences with paintings and installations so monumental that the truth can never be hidden away again.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements