The Scream 2017

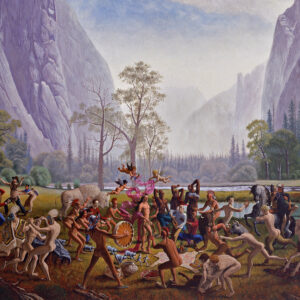

Kent Monkman, The Scream, 2017

Acrylic on canvas, 213.4 x 335.3 cm

Denver Art Museum

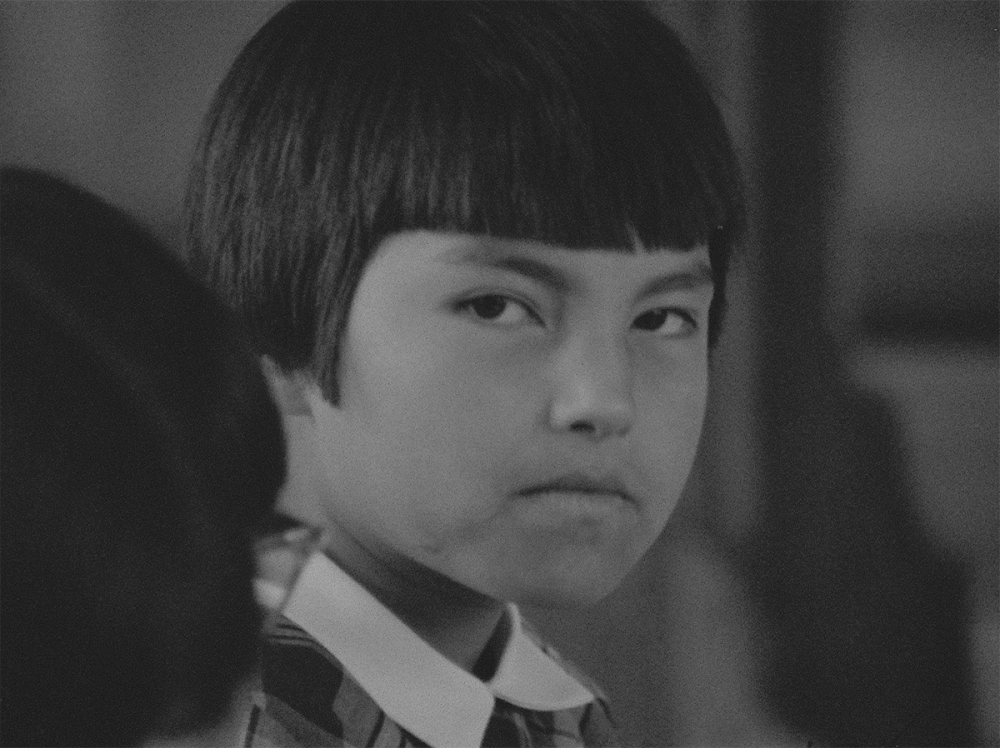

Kent Monkman’s The Scream—which derives its title from The Scream, 1893, by Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863–1944)—references the horrors of the residential school system. In the late nineteenth century, the Canadian government imposed “aggressive assimilation” on Indigenous peoples. More than 150,000 Indigenous children were forced to attend residential schools between the late 1800s and the 1990s. First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children were taken from their parents and placed in institutions whose objective was to strip them of their language, culture, and identity. Many children suffered physical, psychological, and sexual abuse, and several thousand died. Monkman’s The Scream viscerally and unflinchingly captures the violence of these facilities, depicting children being ripped from the arms of their mothers by members of the Catholic clergy and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. At the centre is a mother who lunges forward with her arms outstretched toward her child, who has been pulled away from her by a priest. The work testifies to the Canadian government’s systematic effort to exterminate Indigenous peoples, their languages, and their cultures.

In Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience, the exhibition Monkman curated in 2017, The Scream was part of “Chapter V: Forcible Transfer of Children,” where it hung in a room with black walls. The entrance to the gallery space featured toys and crafts made by students at the Grouard Residential School circa 1925, and these objects carried the cultural identity of the children who incorporated hide and seed beads into their making. The walls were lined with askotâskopison (traditional cradle boards) crafted by mothers for their babies. Some were plain wood frames or chalk-marked outlines suggesting missing and deceased children. In the accompanying brochure written in Miss Chief Eagle Testickle’s voice, the pain is inexplicable: “This is the one I cannot talk about. The pain is too deep. We were never the same.”

The Scream does not relegate its action solely to a colonial past. Monkman recreates the abduction in a modern setting with contemporary clothing, indicating that the forcible removal of Indigenous children from their parents and relations continues—from the time of the Sixties Scoop to the child welfare system of today.

The work has a powerful relationship with Monkman’s haunting black and white film Sisters & Brothers, 2015, which draws parallels between the annihilation of the bison in the 1890s and the devastation inflicted on the Indigenous population by the forced assimilation of children in government- and Church-run institutions. Two years after painting The Scream, Monkman created The Deluge, 2019, which also calls attention to the legacy of residential schools and the continued removal of Indigenous children by child welfare agencies. Hearkening back to the Trail of Tears and the brutal forced relocation of Indigenous peoples by the U.S. government in the 1830s, the painting depicts Miss Chief saving children from the flood of settler cultures displacing Indigenous peoples from their lands in Arkansas.

Since May 2021, through the use of ground-penetrating radar technology, hundreds of unmarked graves of Indigenous children have been discovered in Saskatchewan, British Columbia, Manitoba, and Ontario, prompting calls for accountability from both the Canadian government and the Roman Catholic Church, which ran day-to-day operations at many of the institutions.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements