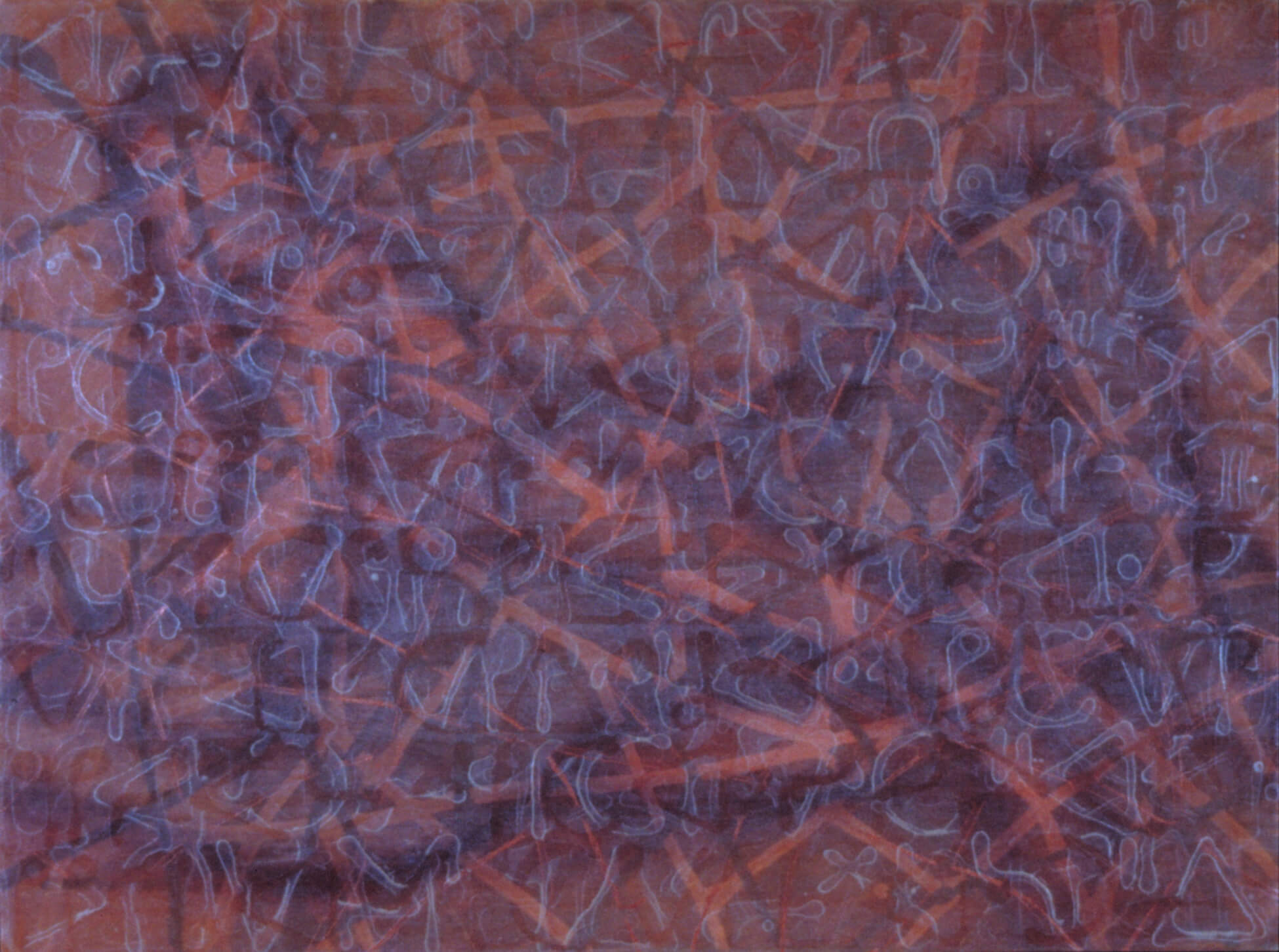

Shall We Gather at the River 2001

Kent Monkman, Shall We Gather at the River, 2001

Acrylic on canvas, 182.9 x 243.8 cm

Collection of the artist

Shall We Gather at the River is part of a series titled The Prayer Language, which was inspired by a book of Cree hymns owned by Kent Monkman’s parents, and the work incorporates Cree syllabics quoted from the hymn of the same name that gives the piece its title. Layers of thick, semi-transparent acrylic paint mimic human skin, with a surface resembling veins, muscles, and bone. Underneath these markings are ghostlike figures sourced from photographs of men wrestling, entwined in either ecstasy or struggle. Intrigued by Michel Foucault’s notion of sexuality as an exchange of power, Monkman explores the body as a site of contention inflected by conquest, struggle, and implicit questions of identity, using his ancestral language of Cree. This act of layering—body, language, and history—is a powerful reference to the impact of Christianity on Indigenous communities, a critical issue Monkman has explored for many years.

Cree was called “the prayer language” on the reserve where Monkman’s great-grandmother was born in St. Peters, Manitoba, and Christianity was part of his personal history, with lasting effects passed along from his great-grandmother to the present. While the invention of Cree syllabics dates to 1840 and is attributed to James Evans, an Anglican missionary in northern Manitoba, many Cree people, including Monkman, believe that syllabics existed on birchbark scrolls and that Evans learned about them through his contact with the Cree community. In Evans’s hands the syllabics were deployed through a non-Indigenous perspective, accentuating the Church’s association with the colonizer. Christianity established its presence through this language, encoding marks signifying teachings of the Bible. Monkman could not speak or read Cree at the time he created this work (he is currently learning the language), but he saw the language as an abstraction, and the syllabics became abstract marks within his art.

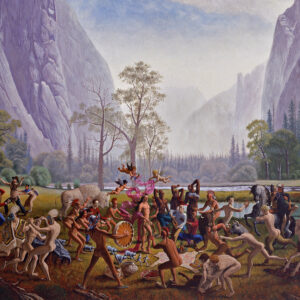

Monkman also addresses sexual power relations in the history of Indigenous and European contact by bringing together elements of hymns and homoeroticism. Some titles in The Prayer Language series are cheeky double entendres that push against Christian sexual morality, such as When He Cometh, 2001. “I was thinking of colonized sexuality,” he explained. “It was through the process of colonization and the impact of the Church and missionaries that resulted in homophobia in our communities.” The series was exhibited at the Indian Art Centre (now the Indigenous Art Centre) in Ottawa in 2001.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements