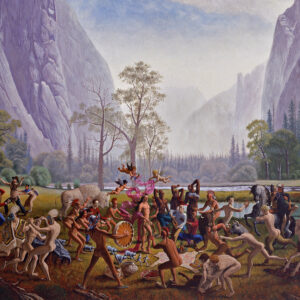

Resurgence of the People 2019

Kent Monkman, Resurgence of the People, 2019

Acrylic on canvas, 335.3 x 670.6 cm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The monumental installation mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) was created for the Great Hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in conjunction with the institution’s 150th anniversary in 2019. For Kent Monkman, the commission represented the pinnacle of many years of work. It consists of two paintings: Welcoming the Newcomers, a visual interpretation of migration to Turtle Island (the North American continent), and Resurgence of the People, which portrays an optimistic path forward to a new future for Indigenous peoples.

Created by a team of ten painters under Monkman’s direction and based on photo shoots that employed about forty models, the project represents the artist’s sophisticated deployment of revisionist history painting. Asserting the continued relevance of representational art as a medium to deliver a message, Monkman addressed histories told through artworks in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan. His works were installed in the museum’s entrance hall, a symbolically charged place of arrivals and departures and a magnet for tourists.

-

Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1851

Oil on canvas, 378.5 x 647.7 cm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

-

Kent Monkman, Welcoming the Newcomers, 2019

Acrylic on canvas, 335.3 x 670.6 cm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Resurgence of the People introduces the theme of migratory agency, reflecting the diversity of the North American settler state. Monkman describes this painting as a conversation between the “arrivals and migrations and displacements of people around the world” and Indigenous generosity. He took inspiration from news images of migrants and refugees fleeing in small boats and used as his main visual source Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1851, by American-German artist Emanuel Leutze (1816–1868), a work in the Metropolitan’s collection that was painted seventy-five years after George Washington victoriously led a boat full of troops across the Delaware River during the American Revolution.

In Monkman’s composition, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle presides over the boat, representing the resilience of Indigenous peoples and the resurgence of values that are essential to the survival of humankind. Mimicking the pose of Washington, she stands tall as she navigates the waters of a cataclysmic world where Indigenous peoples offer salvation to displaced individuals. Her pose also evokes the figure of New York City’s Statue of Liberty, which celebrates the victory of American revolutionaries—only Miss Chief holds an eagle feather instead of a torch. Monkman replaces the flag in Leutze’s painting with the coup stick that is used by Indigenous warriors on the prairies as a sign of bravery in battle, and Washington’s sailors are replaced by Indigenous peoples offering salvation to those cast adrift.

On the opening night of the exhibition at the Metropolitan, the Great Hall was populated with contemporary art curators, directors, and artists, all there to praise Monkman. Miss Chief’s performance was met with a standing ovation. It was truly a celebration marking a moment of change in a step towards decolonization of major American museums. The New York Times relayed, “Miss Chief is an avatar of a global future that will see humankind moving beyond the wars of identity—racial, sexual, political—in which it is now perilously immersed.” It was a sign of things to come. The Metropolitan acquired the diptych in October 2020, and the project has inspired future commissions on the part of museums for Monkman to dig into their collections as a means of reworking and re-addressing colonialist history.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements