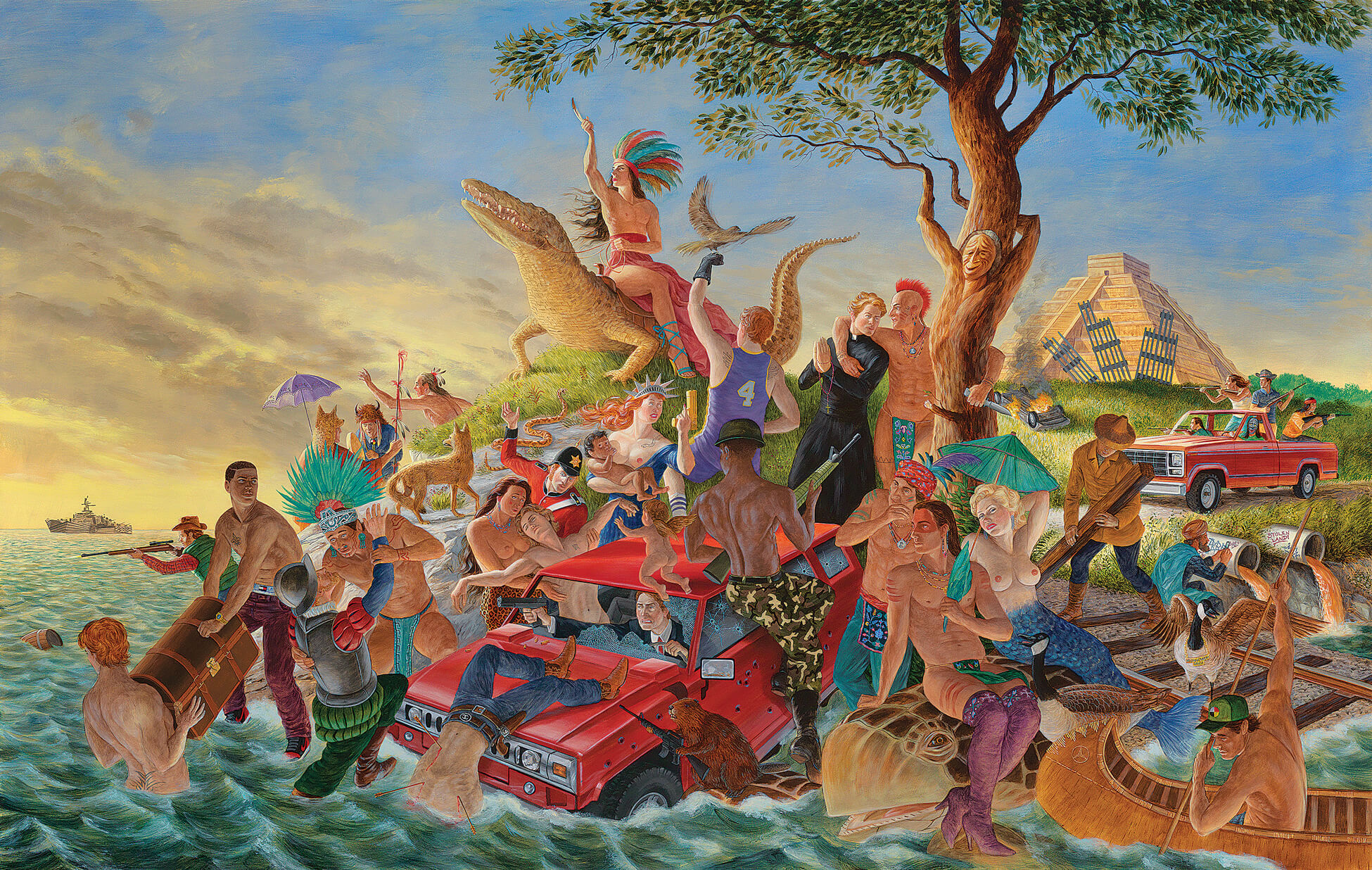

Miss America 2012

Kent Monkman, Miss America, 2012

Acrylic on canvas, 213.4 x 335.3 cm

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

Miss America is the first work in the Four Continents series that Kent Monkman produced between 2012 and 2016, which was shown in its entirety at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery the year it was completed. In a triangular composition, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle is seen riding an alligator, raising a feather to the sky, and holding court over a diverse tangle of figures that include a basketball player, a British soldier, a mermaid that looks like Marilyn Monroe, Indigenous peoples of ambiguous gender identities, and Aztecs and Mayans.

-

Kent Monkman, Miss Europe, 2016

Acrylic on canvas, 213.4 x 335.3 cm

Collection of Daniel L. Bain

-

Kent Monkman, Miss Africa, 2013

Acrylic on canvas, 213.4 x 335.3 cm

Private collection

-

Kent Monkman, Miss Asia, 2015

Acrylic on canvas, 213.4 x 335.3 cm

Claridge Collection

The Four Continents is a reinterpretation of the Rococo ceiling fresco Apollo and the Four Continents, 1750–53, by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770), which Monkman had seen in books in the early 2000s and in person at the Würzburg Residence in Germany, the former home of the prince-bishops, in 2013 or 2014. At each edge of the curved ceiling are symbolic representations of Europe, Asia, Africa, and America. In Monkman’s series, each continent is personified by a Two Spirit sovereign with Miss Chief playing the roles of Africa, America, Asia, and Europe. His reworking of Tiepolo’s fresco challenges the history of the so-called Enlightenment or Age of Reason in the 1700s, revealing a barrage of colonialist aggression on a global scale. Monkman turns Tiepolo’s pageant of benevolent “exploration” into something resembling an action movie, where violence and sexual desire play out with warnings of environmental destruction and terrorism.

Miss America incorporates a mash-up of symbolism: a Catholic priest accepts the one-armed embrace of a Mohawk warrior; a canoe features a Mercedes Benz logo; and a man wears a wolfskin hood and carries a pale lavender parasol. There is also a homoerotic image of Saint Sebastian in jeans, cowboy boots, and a belt with a Chanel logo. The inclusion of emblems of modernity (like the logos) alludes to the multiple ways in which trade and theft are manifested in global narratives. “I wanted to think about a contemporary version of globalism and how consumer culture and corporate culture have impacted indigenous people on the various continents,” Monkman said.

Tiepolo’s cycle uses the aesthetics of classical antiquity coupled with Enlightenment worldviews to bring order from chaos—the artist has organized the entire world in his fresco. Monkman, although appropriating Tiepolo’s compositional and iconographic tools, piles Indigenous and non-Indigenous bodies into a climax of the colonizing of the Americas that simultaneously asserts and undermines the “rationalism” of our age. By monumentalizing the Indigenous experience in the Americas, he posits a different historical trajectory that skewers the apocryphal fantasies of colonial supremacy. Indigenizing a canonical piece in the history of European art, he creates a masterwork of subversion and sensuality that responds to and engages with anti-colonial discourse.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements