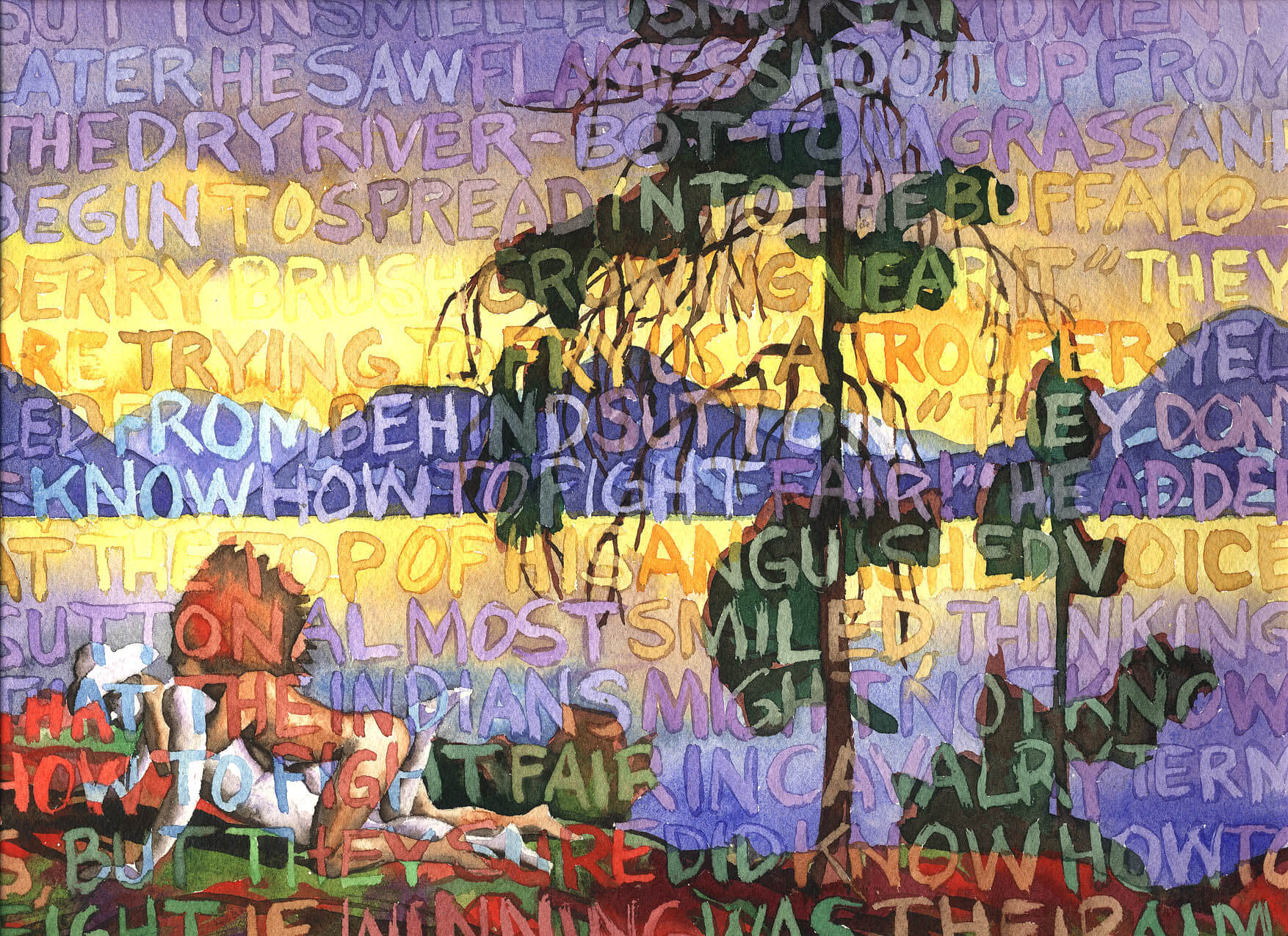

Jack Pine 2001

Kent Monkman, Jack Pine, 2001

Watercolour on acid-free paper, 22.9 x 30.5 cm

Private collection

In Jack Pine, Kent Monkman appropriates the iconic work The Jack Pine, 1916–17, by Tom Thomson (1877–1917), subverting the original painting’s visual language and meaning. In this watercolour, Monkman obscures the famed Canadian landscape with a scrim of violent, racist text from a pulp Western novel that he culled from his research on the fetishization of Indigenous men. Two men are depicted near the base of the tree, one wearing a cowboy hat, and the other a feathered headdress. Their ambiguous embrace implies both a struggle and a sexual act, and the land is the focus of the encounter. The text appears camouflaged in parts of the composition, yet it resonates clearly in red on the warrior’s body and blue over the cowboy’s body. After his early explorations in abstraction, Monkman wanted to find a means of deeper and clearer communication, so he turned toward figurative imagery, and Jack Pine is part of this shift in his art.

When he took up representational painting, Monkman began by depicting people in ambiguous landscapes. He later quoted directly from well-known paintings by Group of Seven artists. With a focus on homosexuality, he decided to include two key players in his new narrative, creating, in his words, “one as a brown man and one as a white man; one a ‘cowboy’ and the other an ‘Indian.’” Monkman’s objective was to use sexual power dynamics to explore issues of Christianity and colonialism, with particular emphasis on how Indigenous peoples accepted homosexuality and how the Church repressed it.

Other works in which Monkman referenced the Group of Seven include Superior, 2001, where the artist lifts the composition from Group of Seven member Lawren S. Harris (1885–1970). In his characteristic humorous style, he turned the tree stump in the painting North Shore, Lake Superior, 1926—which Harris intended as a majestic symbol of nature’s regenerative power—into a blatant phallus. These works take aim at male artists’ colonialist chauvinism, as well as their notorious exclusion of women. The use of layered image and text is reflective of the complex stratification of power, eroticism, morality, and xenophobia at the root of Canadian identity.

Monkman has identified this series as part of an important development in his work, noting:

My Group of Seven interventions were transitional influences from my Prayer Language series; I made a suite of watercolours that shows my visual transition from abstraction to landscape. I focused on the Group of Seven because I was interested in the graphic quality of their work. Their landscape paintings suited the more graphic style of my earliest watercolour pieces after the Prayer Language, in which I continued to experiment with an overlay of text over the work…Taking on this series was a reflection on conflicts around land in North America. Looking at their work, I was struck by how the Group of Seven painted Canadian landscapes as empty and unpopulated, devoid of people. The Canadian artists in the Group of Seven “disappeared” first peoples and reinforced concepts of the North American landscape as an empty wilderness. I wanted to challenge that.

Monkman’s Jack Pine, among other paintings in the series, was installed in the Members’ Lounge of the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario, as part of his 2004 residency there. This can be read as an ironic placement, given the McMichael’s history as the institutional authority on Canadian identity in the work of the Group of Seven.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements