Known for his provocative interventions into Western European and American art history, Cree artist Kent Monkman (b.1965) grew up in Winnipeg, passionate about art and profoundly aware of how colonialism had affected Indigenous communities. Drawing on early experiences in illustration and theatre, he has worked in painting, photography, installation, film, and performance. Through his gender-fluid alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, a shape-shifting, supernatural being, Monkman created opportunities to confront colonial injustice, challenge received notions of history, advocate for social change, and honour the resistance and resilience of Indigenous peoples. His major exhibitions in Canada and the United States have been unprecedented interventions of decolonization.

Early Years

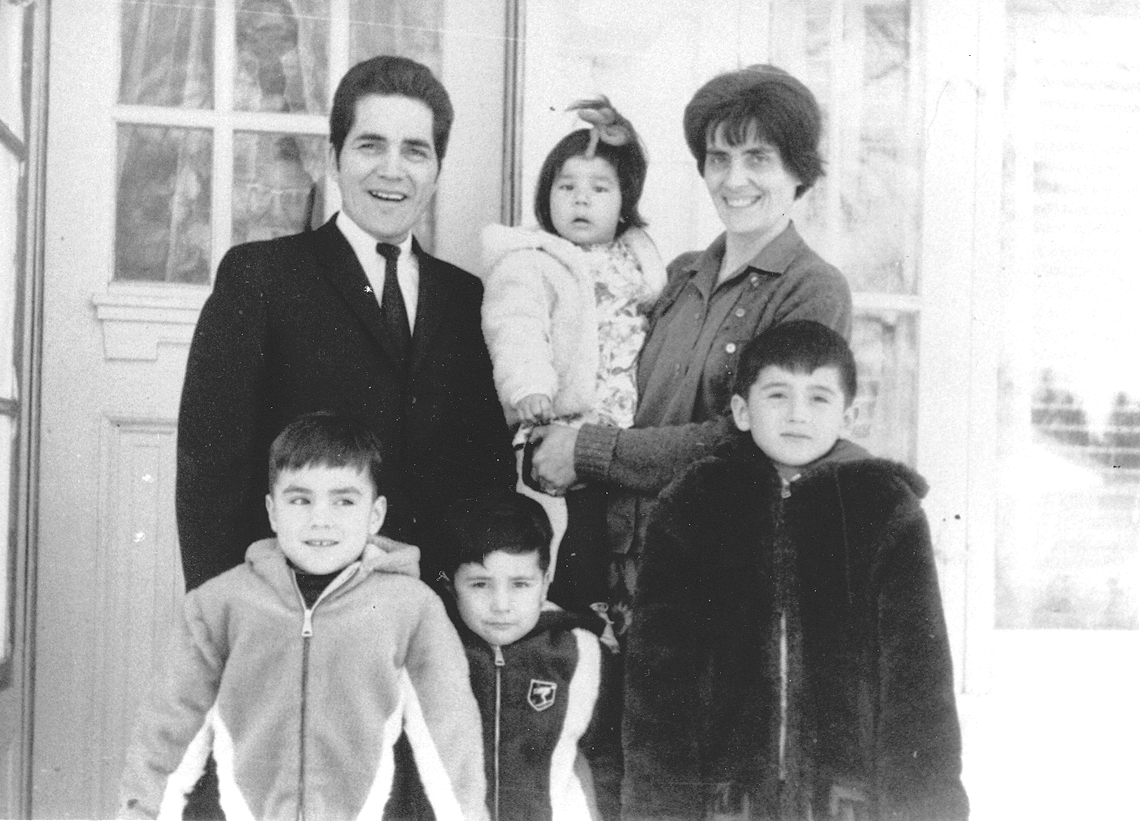

Kent Monkman, a member of the Fisher River Cree First Nation of northern Manitoba, was born in 1965, the third of four children. His Anglo-Canadian mother, Rilla Unger, and his Cree father, Everet Monkman, visited Rilla’s hometown of St. Marys, Ontario, for his birth, but they returned soon after to northern Manitoba and the Cree community of Shamattawa First Nation, where they had been living with Monkman’s two older brothers. Before they married, Monkman’s mother had been a schoolteacher. His father grew up on Lake Winnipeg and initially earned a living as a commercial fisherman. After moving to Winnipeg, he supported his family as a social worker and by driving cabs and selling vacuums door to door.

Hoping to secure a better environment for his children than the one he had experienced as a child, Everet moved the family to the middle- and upper-class neighbourhood of River Heights so that Monkman and his siblings could attend one of the better public schools in the city. However, many in the community did not welcome Everet. “There were people who wouldn’t talk to my dad when he moved into the neighbourhood,” Monkman recalls. “It was hard for him to accept that, but he knew that putting his kids into better schools was going to give us a better shot down the road.”

Monkman was close to his paternal great-grandmother, Caroline Everette, who spoke only Cree and lived with his family on and off until he was ten. He felt a strong connection to her birthplace, St. Peters, Manitoba, and considers it his ancestral home. Caroline Everette’s life was marked by the cruelties and oppression of Canada’s colonizing forces. Her community was subject to Treaty 5 between Her Majesty the Queen and the Saulteaux and Swampy Cree Tribes of Indians at Beren’s River and Norway House. Signed in 1875, the same year as Everette’s birth, the treaty resulted in her family being forcibly relocated three times. Only three of her thirteen children survived into adulthood. A number of her children were forced to attend residential school.

The strength of Monkman’s family within the history of Canadian racism, colonization, Christianization, residential schooling, and language loss deeply informs his work. As he has said, “I was fortunate enough to have parents and grandparents who were very confident in knowing who they were and who were confident in their own culture. They knew that you can exist in the modern world and still carry your roots and your culture with you.”

Though the household’s modest finances did not allow for many toys or extracurricular activities, Monkman took up art with his parents’ encouragement. At an early age he was already using coloured pencils to produce one-page images laden with stories. “My whole identity as an artist was basically shaped very early, as a kid,” he notes. He was fortunate to be one of two children in his elementary school selected to take free Saturday morning classes at the Winnipeg Art Gallery—his parents would have struggled to afford them otherwise. Having access to high-level art instruction changed his life: “I felt such a sense of belonging at the Winnipeg Art Gallery because I spent so much time there as a kid, not just in the art classes, but walking through the galleries.” He had a book of paintings of horses that inspired him—it included works by Honoré Daumier (1808–1879), Théodore Géricault (1791–1824), Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c.1525–1569), and Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). In 1990 he saw an exhibition of work by Saulteaux artist Robert Houle (b.1947), and the inspiration of Houle’s modernist approach and the experience of seeing an Indigenous artist’s work amplified his feelings of connection.

Another Winnipeg institution would have a different, yet equally important, impact. Monkman remembers seeing the dramatic dioramas featuring mannequins dressed in traditional Indigenous clothing on field trips to the Manitoba Museum. These tableaux depicted Indigenous peoples prior to the arrival of settlers, as if frozen in time, hunting bison or camping in idyllic prairie landscapes. From an early age he perceived a dramatic dislocation between these romanticized presentations and the enduring and catastrophic fallout of colonization that was evident outside the museum, where many Indigenous people were living on the streets. Winnipeg is a city riven by race and class, and most of the Indigenous population live in the culturally diverse, economically challenged North End, not the predominantly middle-class, white, Anglo-Saxon neighbourhood of River Heights, where the Monkman family resided. At the museum, Monkman was very aware that he looked different from his white classmates—a contrast that he embraced. In his words, the visits “were inspirational and scarring at the same time.”

Studies in Art and Early Career

In 1983, having graduated from Kelvin High School at the age of seventeen, Monkman enrolled in the Illustration program at Sheridan College of Applied Arts and Technology in Brampton, Ontario. His older brother was there a year ahead of him, so Sheridan was familiar. As well, the curriculum offerings, which included fundamental courses in painting and drawing, appealed to him. At the time, he was interested in artists such as Bob Boyer (1948–2004), Joane Cardinal-Schubert (1942–2009), Jane Ash Poitras (b.1951), Robert Houle, and Ivan Eyre (b.1935). After completing his degree in 1986, he worked in Toronto as a designer for Native Earth Performing Arts, which was led by artistic director and Cree playwright Tomson Highway (b.1951). The highly acclaimed organization is the oldest professional Indigenous theatre company in Canada.

-

Kent Monkman, set for Floyd Favel’s Lady of Silences at Native Earth Performing Arts, Toronto, 1993

-

Kent Monkman, sets and costumes for Night Traveller, Tipiskaki Goroh, Canada Dance Festival, Ottawa, 1994

-

Kent Monkman, sets and costumes for Night Traveller, Tipiskaki Goroh, Canada Dance Festival, Ottawa, 1994

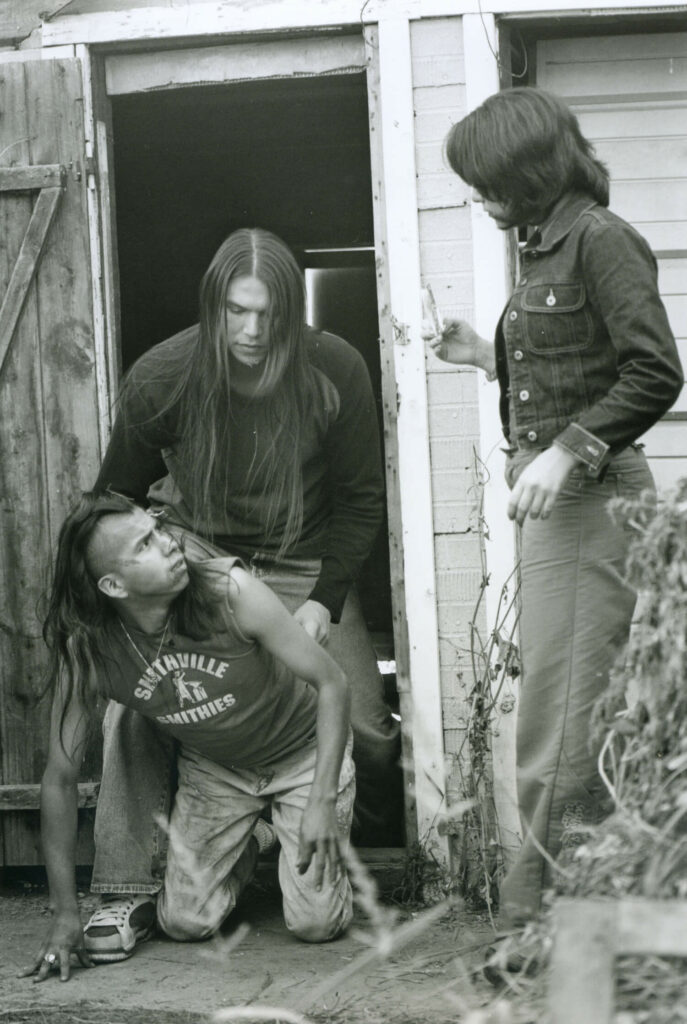

Monkman created sets and costumes for the plays Lady of Silences, 1993, by Floyd Favel and Diva Ojibway, 1994, by Tina Mason, among other productions. His work occurred at a most opportune time: in the 1970s, Indigenous theatre grew rapidly, and by the 1980s it had become a crucial part of mainstream Canadian theatre. Native Earth Performing Arts had major successes with The Rez Sisters, 1986, and Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing, 1991. Monkman’s talents in theatrical design, along with his interest in performance, would later become significant influences on his art practice. He notes, “My time with Native Earth was a period when I started working collaboratively with other artists. Designing for theatre also introduced my practice into a third dimension which led to film, video, and installations.”

Monkman also worked as a freelance illustrator and acquainted himself with the city’s cultural scene. There were points when he struggled financially, and he even questioned his path as an artist. He ran independent exhibitions with other artists out of his own studio space, and in 1991 participated in his first professional exhibition, The Toronto Mask Show at Lake Galleries, Toronto.

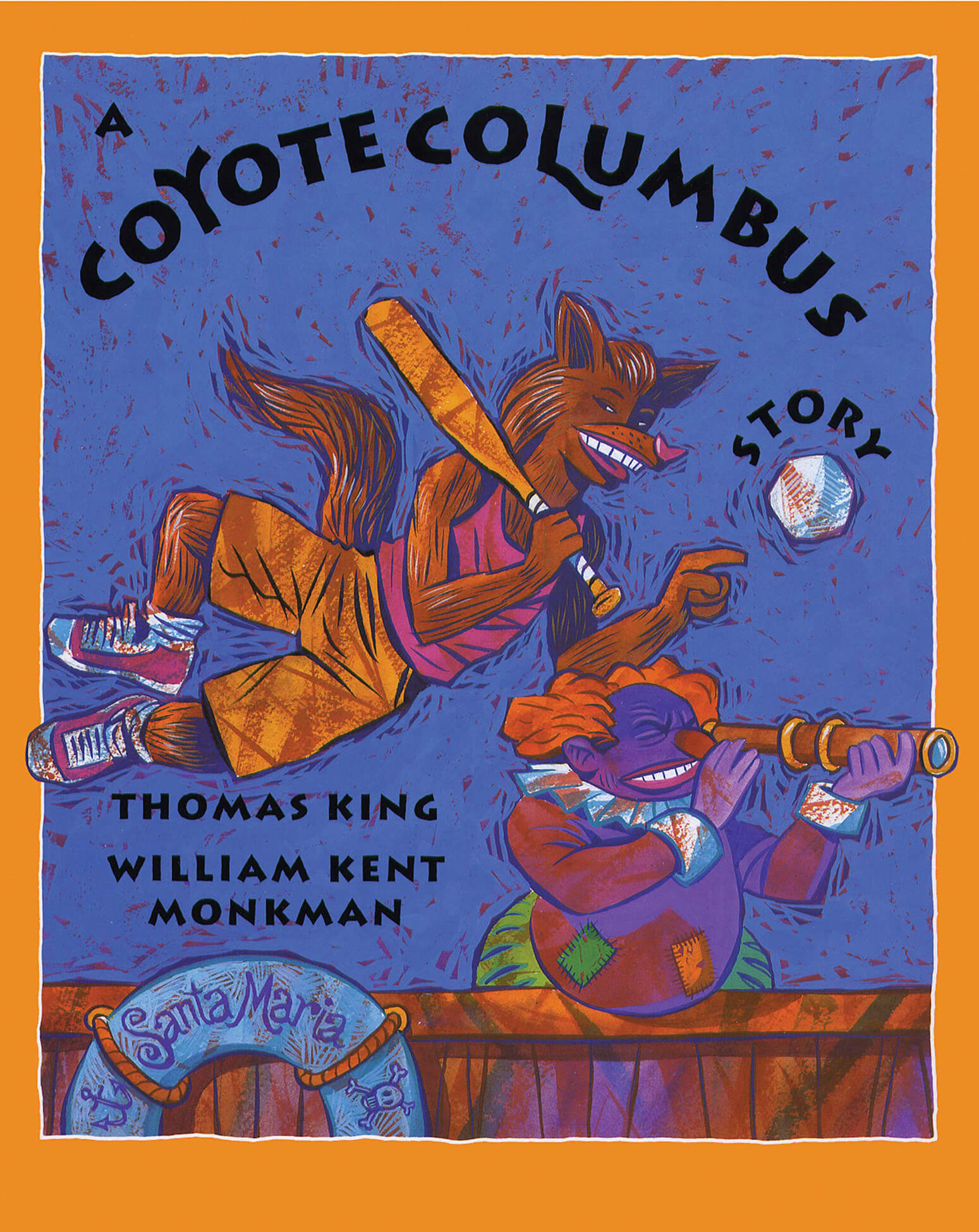

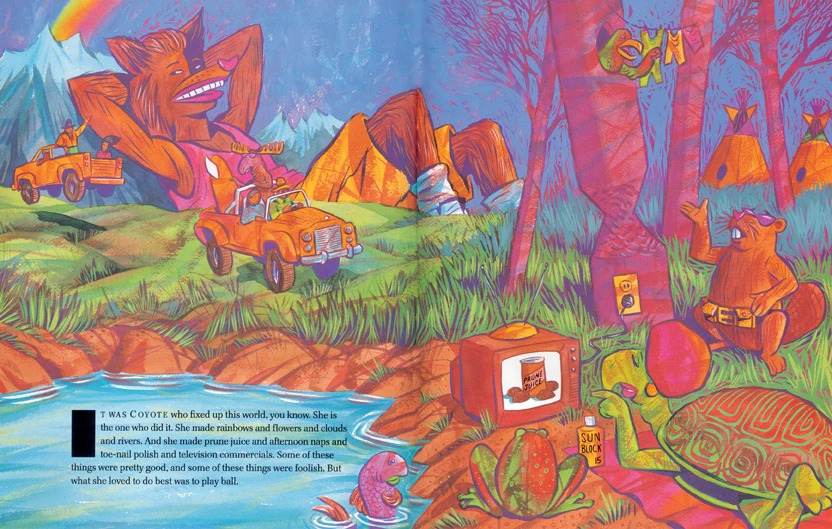

Monkman first gained public attention when he illustrated Cherokee writer Thomas King’s children’s book A Coyote Columbus Story (1992), which was written as a protest against the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s 1492 invasion of the Americas. Monkman’s vibrant, cartoon-like renditions of the trickster named Coyote, combined with King’s humorous, deeply powerful text, caused political outrage. A Coyote Columbus Story counteracted the dominant colonialist doctrine that celebrates explorers and the “discoveries” they made. In contrast to miyo-wîcêhtowin, the Cree term for living in harmony together, the explorer’s discovery was depicted as a violent and hostile takeover of land—a perspective that would become a defining feature of Monkman’s oeuvre.

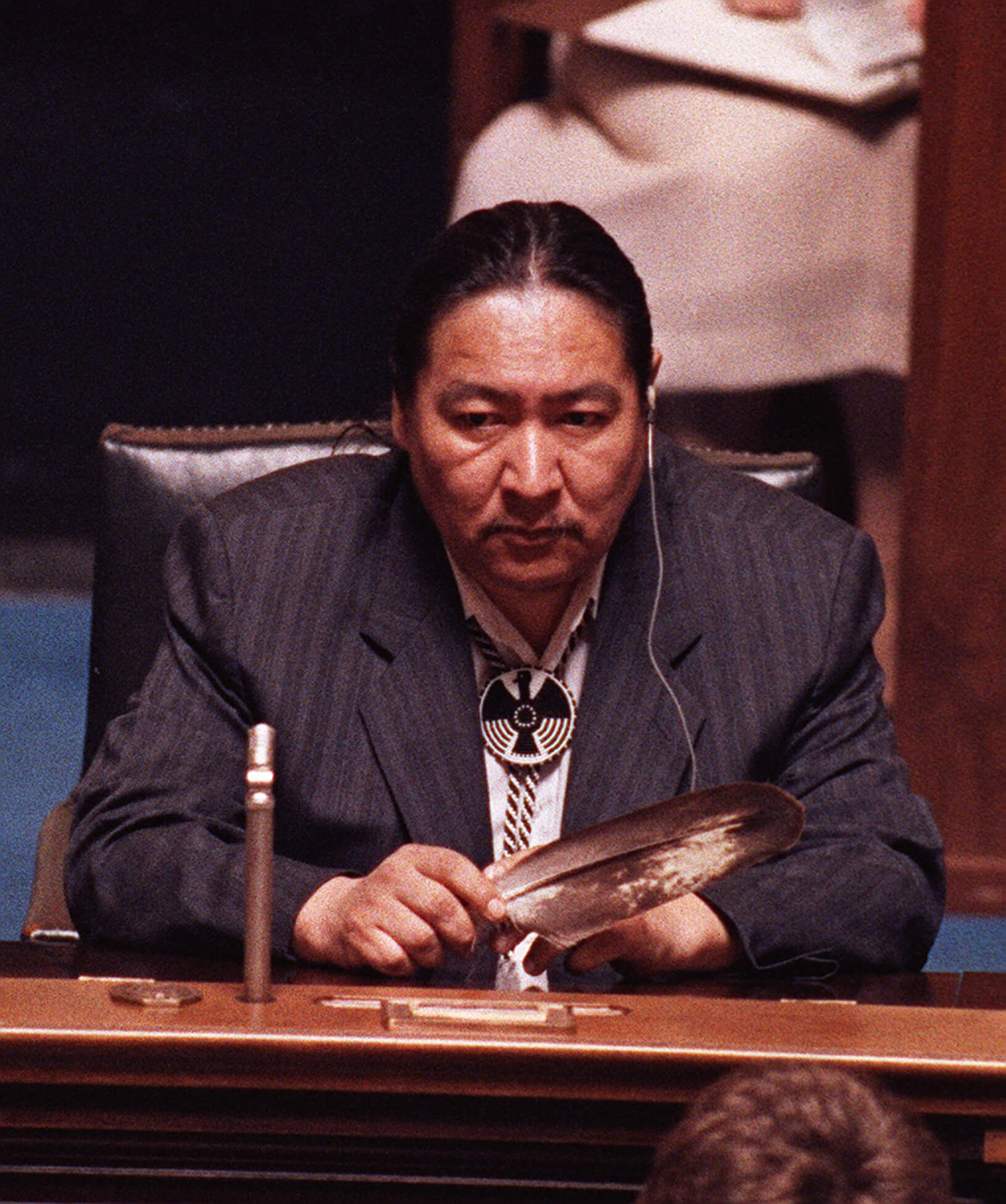

As Monkman’s artistic career was developing, political events were galvanizing Indigenous solidarity. Massive land claims were proceeding in British Columbia, Ontario, and the Yukon. In 1989, the Quebec government announced plans to begin Phase 2 of the James Bay hydroelectric project, a decision that resulted in major protests (and the eventual suspension of the work). The following year, Elijah Harper, a Cree member of the Manitoba Legislative Assembly, said no to the Meech Lake Accord, the proposed constitutional legislation that would have denied recognition of Indigenous peoples while affirming Quebec as a distinct society with special status.

In the summer of 1990, a land dispute exploded between the Quebec town of Oka and the Mohawks of Kanehsatà:ke, who were protecting a burial ground from being developed into a golf course. Monkman was inspired by the artists and activists involved, including Ellen Gabriel, also known as Katsi’tsakwas, who was the official spokesperson chosen by the People of the Longhouse, and Joseph Tehawehron David, who became known as the protests’ warrior; the crisis was recorded in the film Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993) by Alanis Obomsawin (b.1932). Shortly after the crisis ended, Phil Fontaine, a former national chief of the Assembly of First Nations, disclosed the abuse he had experienced in the residential school system. His story shed light onto one of the darkest periods in Canadian history. The following year, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney launched the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, a national inquiry that examined the relationship between Canada and Indigenous peoples.

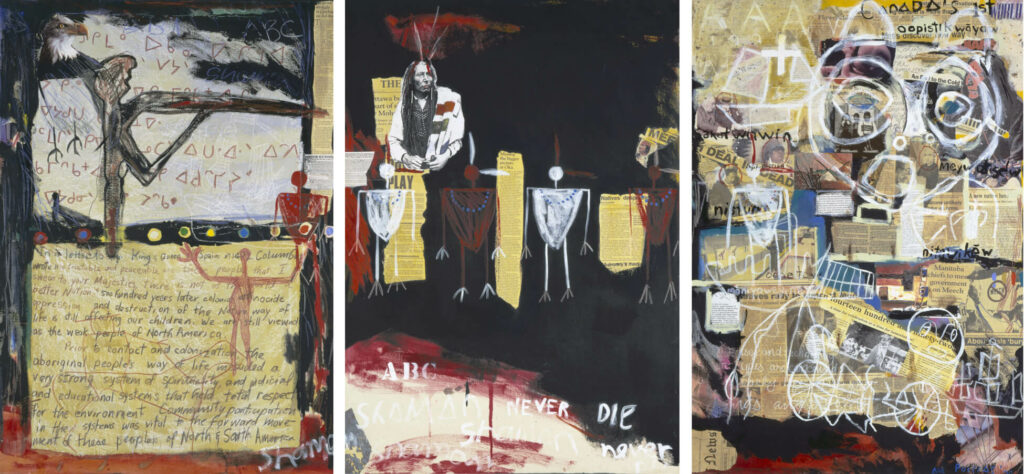

In 1992, amid the celebrations on both sides of the Atlantic marking the 500th anniversary of the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Western hemisphere, two landmark exhibitions confronted colonialism. Indigena: Contemporary Native Perspectives in Canadian Art at the Canadian Museum of Civilization (now the Canadian Museum of History) in Gatineau, Quebec, was curated by Lee-Ann Martin and Gerald McMaster (b.1953), and Land, Spirit, Power: First Nations at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, was curated by Robert Houle, Charlotte Townsend-Gault, and Diana Nemiroff. In addition to further exposing him to the work of Bob Boyer and Jane Ash Poitras, these shows introduced Monkman to a number of Indigenous artists, many from an older generation, including Carl Beam (1943–2005), Edward Poitras (b.1953), Mike Macdonald (1941–2006), Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun (b.1957), Rebecca Belmore (b.1960), Robert Davidson (b.1946), Alex Janvier (b.1935), and Zacharias Kunuk (b.1957).

Both exhibitions marked unprecedented critical attention for contemporary Indigenous art, which many museums, including the National Gallery of Canada, did not exhibit prior to the 1980s. Yet, even as these artists achieved mainstream recognition, Monkman and a younger generation of Indigenous artists working in performance, new media, photography, and installation, including KC Adams (b.1971), Mary Anne Barkhouse (b.1961), Terrance Houle (b.1975), and Brian Jungen (b.1970), were seeking to redefine the future of Indigenous art.

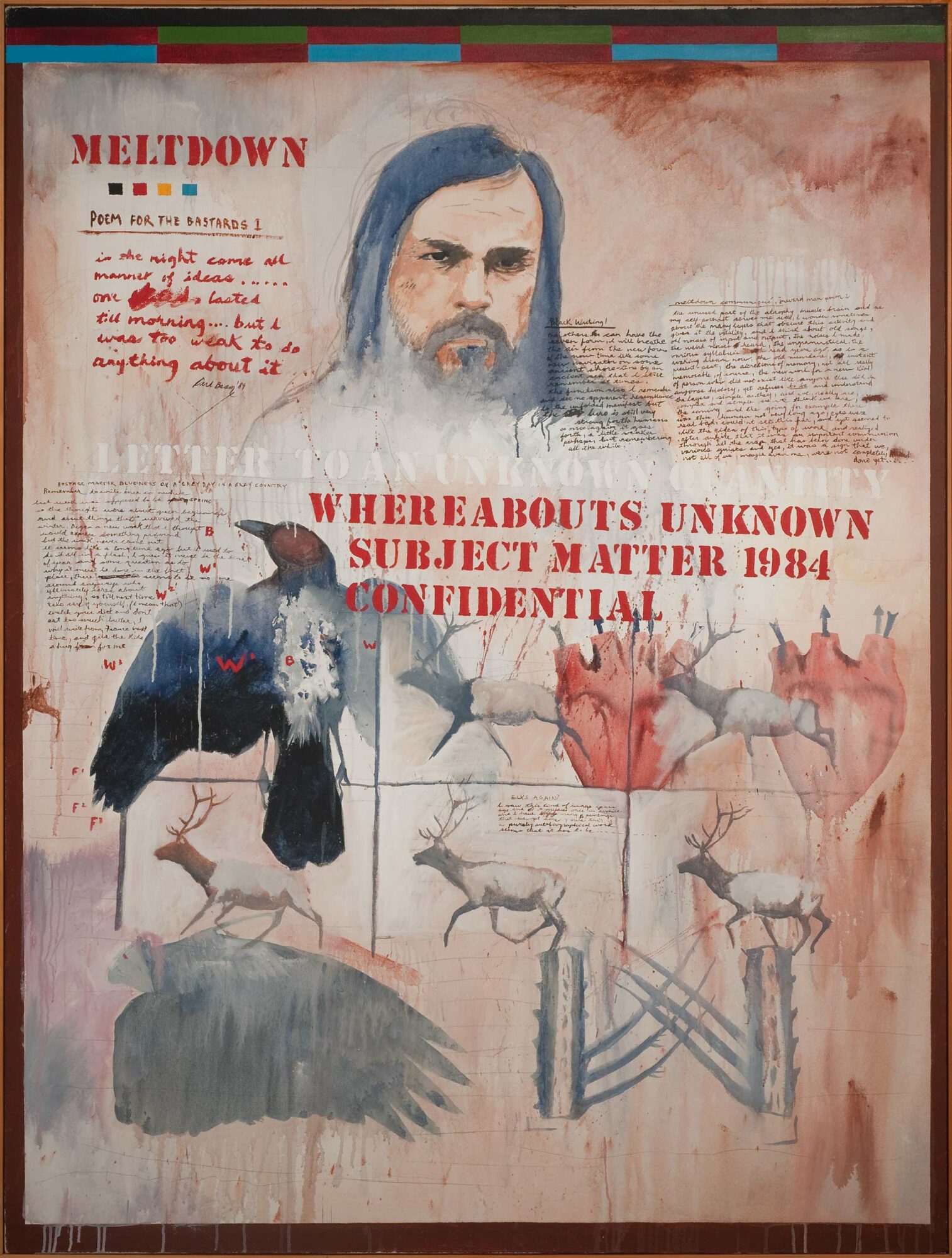

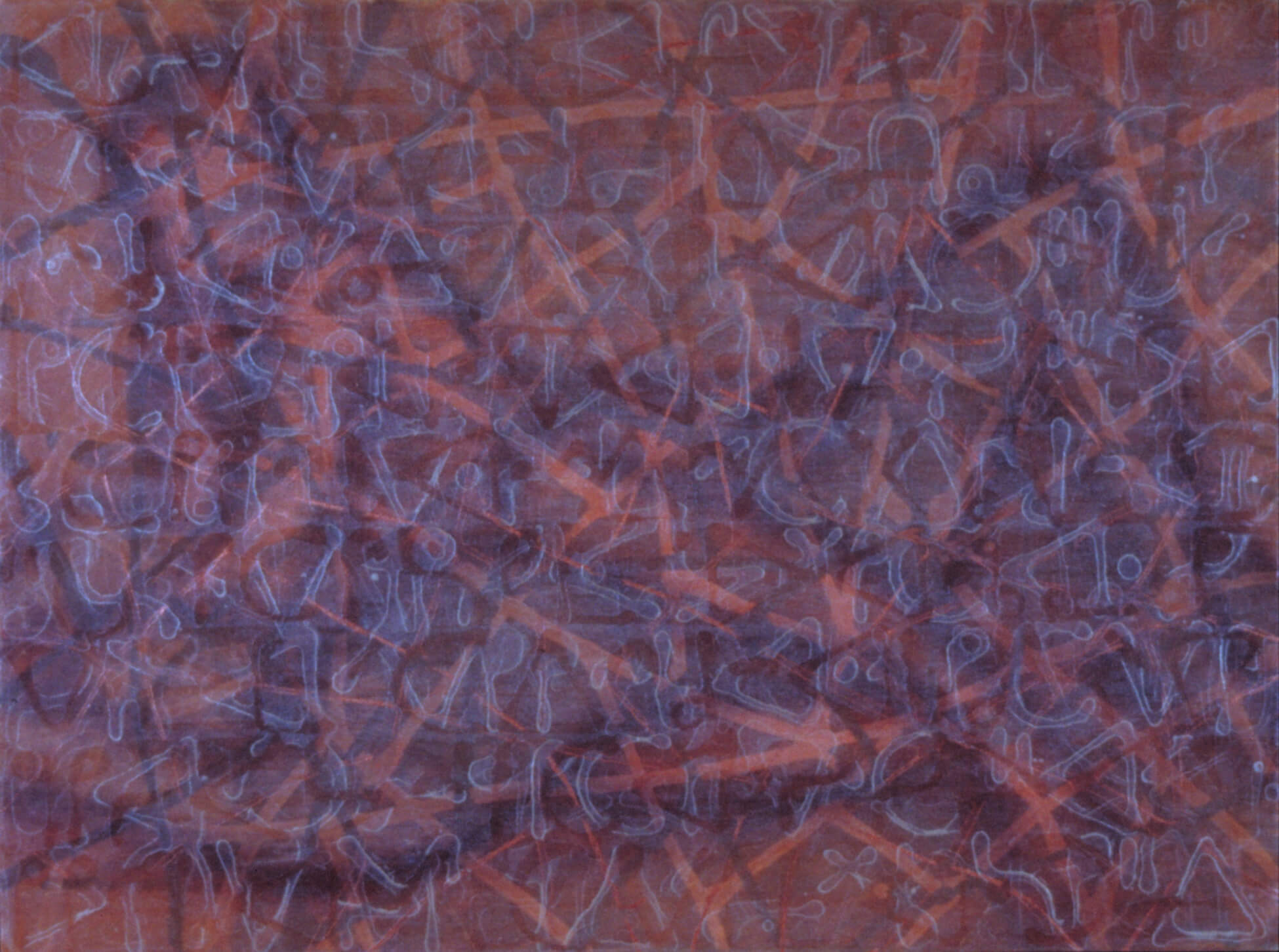

As he continued his training at various institutions in Canada and the United States—including the Banff Centre for the Arts, Alberta, in 1992; Sundance Institute, Los Angeles, in 1998; and the National Screen Institute, Winnipeg, in 2001—Monkman was simultaneously making his mark as an artist. He had been interested in Abstract Expressionism since the late 1980s, and he had an eye on this style before he was making his own works in this vein. He began experimenting with abstraction in the 1990s while reflecting on the impact of Christianity and government policies on Indigenous communities.

In a major series of abstract paintings titled The Prayer Language and including works such as When He Cometh, Shall We Gather at the River, and Oh For A Thousand Tongues, all 2001, Monkman combined syllabics taken from his parents’ Cree hymn book with ghostly, homoerotic images of men wrestling. The translations of Christian hymns into Cree became a vehicle to investigate questions of sexuality and power and the complex history of Indigenous and European relations. Prior to contact, many Indigenous cultures honoured gender-fluid identities and same-sex attractions; it was Christianization that instilled shame and judgment about gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people. With this series, Monkman not only addressed colonialism but also drew inspiration from his own history and imprinted his sexuality on his work.

Monkman did not have an easy time accepting his own sexuality. However, in his thirties, he began to express his Two Spirit identity in his art. He compared his upbringing to that of a friend, artist and illustrator Maurice Vellekoop (b.1964), who talked of “the legacy of fear and shame” they dealt with because of their family’s religious beliefs (like Monkman, Vellekoop has chosen to explore sexuality in his art through projects such as the book Pin-Ups [2008]). Monkman had relationships with men and women, including artist and filmmaker Gisèle Gordon (b.1964), an early supporter of his work who remains a close friend and collaborator—the two have worked together on most of his film and video projects, such as Blood River (2000) and Shooting Geronimo (2007), as well as exhibitions. When he eventually accepted that he preferred relationships with men, his family was “ultimately supportive.”

New Directions in Painting

Around the year 2001, Monkman continued his explorations with watercolour. Searching for clearer communication with viewers, he turned from abstraction to representational art. He made several works depicting male figures in simplified yet ambiguous landscapes, but, unsatisfied, he began recreating a series of paintings by Tom Thomson (1877–1917) and Group of Seven artists such as Lawren S. Harris (1885–1970). He focused on iconic pieces, including Thomson’s The Jack Pine, 1916–17, and Harris’s North Shore, Lake Superior, 1926. The romanticized images of the Canadian landscape as an unpopulated wilderness became significant to Monkman, who regards history as a mythology forged from relationships of power and subjugation. For Monkman, these landscapes are representative of a national identity—one that shows no evidence of Indigenous life on Turtle Island—needing to be countered.

In works such as Superior, 2001, Monkman inserted couplings between submissive cowboys and dominant “Indians” into appropriated historic landscapes (in this case, from Harris), then overlaid the images with violent and racist texts culled from pulp Western novels and explicit narratives from gay erotic fiction. His objective was to use sexual power dynamics as a means of exploring larger issues of Christianity and colonization. These watercolours were serious, but their use of humour was instrumental, as it drew attention to a difficult subject matter.

Monkman also embarked on a series of acrylic paintings inspired by nineteenth-century representations of the North American West. He recalls, “When I was completing The Prayer Language series around 2000–1, I was drawn towards landscape paintings as a way to speak more specifically about Indigenous/settler conflict.” He became particularly fascinated with Romantic artists who depicted Indigenous men as doomed “noble savages,” perpetuating a myth that Indigenous people were a “dying race,” while propagating their own personas as heroic adventurers. Famous works by artists such as Paul Kane (1810–1871), John Mix Stanley (1814–1872), and Thomas Cole (1801–1848) were critical sources. He was also affected by the monumental canvases of American artist Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902), in which Indigenous peoples, if portrayed at all, were miniscule keepers of nature, appearing as small players in his panoramic, majestic views of the West. Monkman reproduced paintings in the vein of Cole’s The Garden of Eden, 1828, with masterful accuracy but revisionist intent, exposing the inherent racism of the original works.

Monkman decided to move away from the use of text and focus on landscapes, in which he included figures from frontier mythology such as trappers, pioneers, missionaries, and explorers, as well as “cowboys and Indians” trading, fighting, and engaging in sexual antics. One of the earliest pieces in the series was Daniel Boone’s First View of the Kentucky Valley, 2001, quoted from a work of the same title by William Tylee Ranney (1813–1857).

Research also led Monkman to Charles Ferdinand Wimar (1828–1862), who is known for his “abduction” paintings in which Daniel Boone’s daughter Jemima is snatched by seemingly dangerous Indigenous men. Monkman’s humorous yet poignant retaliation of this legend is evident in his Captivity paintings, such as The Rape of Daniel Boone Junior, 2002, where he reverses the narrative by replacing the image of Jemima Boone with a half-nude Daniel Boone, who prances gleefully out of a canoe guided by two Cherokee Shawnee. It was a Jean A. Chalmers grant from the Ontario Arts Council in 2003 that finally gave Monkman time to produce what he called “pivotal” work, and he was able to unleash his “mature direction as an artist.” He created paintings for his Moral Landscape series, riffing on compositions by nineteenth-century artists like Bierstadt, Kane, and Alfred Jacob Miller (1810–1874) in works including Red Man Teaches White Man How to Ride Bareback, Pilgrim’s Progress, and Fort Edmonton, all 2003.

Monkman’s new direction was grounded in the history of Canadian art, as well as a departure from it. He was aware of the art historical lineages born from abstraction of the 1950s and 1960s, found in movements such as Abstract Expressionism in New York and Painters 11 in Toronto. Abstraction in Canada was a reaction against what was idealized by the Canadian establishment for many years, art embodied by the Group of Seven, whose members promoted landscape painting as a distinctly Canadian art form. Both movements were not copacetic to representing the nation through an Indigenous lens. Monkman’s painting gradually evolved, becoming increasingly socially and culturally pointed and revealing a new consciousness in revisiting and revising history not previously evident in Canadian art. By employing techniques related to nineteenth-century painting, Monkman was able to return an Indigenous presence not only to art history but to history itself.

The Arrival of Miss Chief Eagle Testickle

In 2004, as part of a three-week visiting artist program at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., Monkman was given access to the collections at this museum and others affiliated with it. He came across the painting Dance to the Berdash, 1835–37, by American artist George Catlin (1796–1872), a work he had previously only encountered as a reproduction in books. Seeing this image, which depicts a ceremonial dance celebrating a Sac and Fox Two Spirit person, prompted Monkman to create a persona that would embrace and honour this tradition.

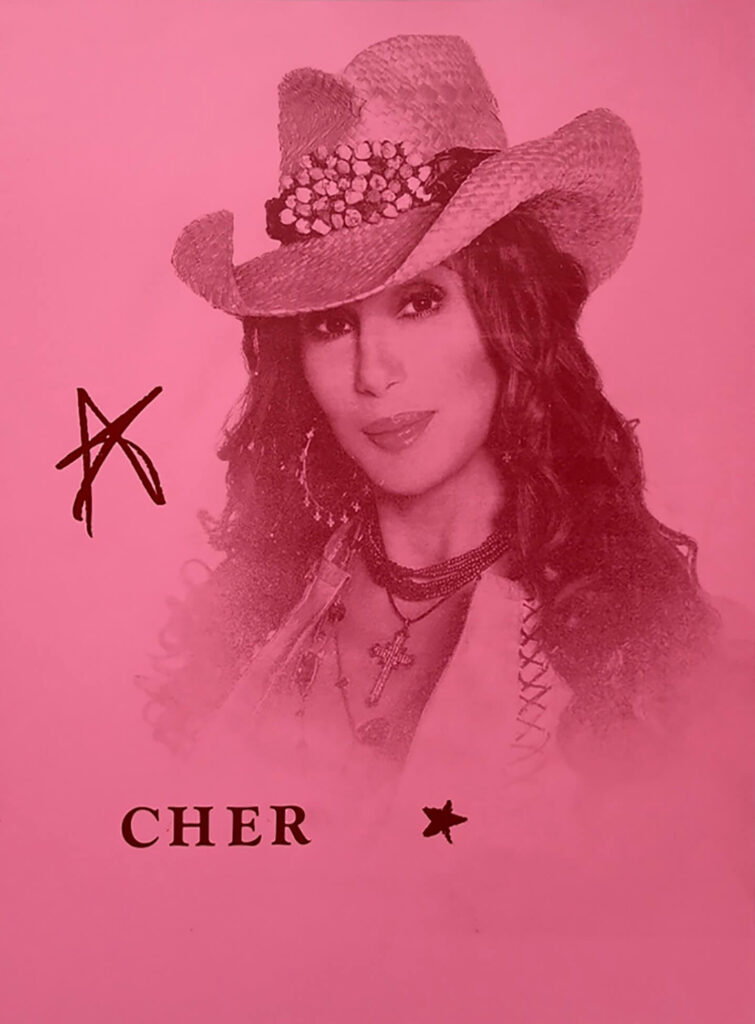

The idea of sexuality and gender as fluid, an accepted element of many Indigenous cultures, was something that Europeans did not understand, as Catlin’s disparaging and racist remarks in his journal indicate. When Monkman looked for a figure who could “live inside his work,” a person who could represent empowered Indigenous sexuality, study European settlers, and ultimately reverse their gaze, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle—or Miss Chief for short—was born. The name is a play on the words “mischief” and “egotistical.” Early on, Monkman also incorporated the name “Cher” (or “Share”), a reimagining of the pop star and gay icon, who the artist noted “had her ‘half-breed’ phase which was glamorous and it was gender bending at the same time.” In the video for the 1973 hit song “Half-Breed,” Cher is seen riding a horse, wearing a white feathered headdress and beaded breastplate and loincloth.

Another significant element not lost on Monkman was Catlin’s fondness for inserting himself into his pictures as a handsome and heroic central player. Miss Chief’s own presence in Monkman’s work was announced subtly, prior to her appearance. Her signature appeared as author of the painting Ceci n’est pas une pipe, 2001 (the title of which alludes to a famous work of the same name by the Belgian surrealist René Magritte [1898–1967]), in the form of the initials S.E.T. (Share Eagle Testickle), and her spirit was insinuated in the composition’s sexually explicit image of an “Indian” warrior mounting a cowboy.

The first visual record of Miss Chief is in Portrait of the Artist as Hunter, 2002, where nearly naked Indigenous riders on horseback race into a herd of buffalo across a majestic prairie landscape. Whereas artists like John Mix Stanley, Paul Kane, or Catlin would have portrayed such a scene as a lament for the past, Monkman transforms it through the inclusion of two distinctive figures: a cowboy (naked except for chaps), who is being pursued by Miss Chief, the diva warrior wearing a pink headdress, fluttering loincloth, and stiletto heels. She makes another poignant appearance in Study for Artist and Model, 2003, a work that can be considered a self-portrait (it is signed with the initials S.E.T.). Positioned with her back to the viewer, she is painting a glyph of her model on a piece of birchbark. At this point in Monkman’s career, Miss Chief becomes firmly established as the “other self.” His identity is subsumed into hers, and the relationship between artist and subject becomes ambiguously ever changing.

Like the Cree trickster wîsahkêcâhk, whose adventures are mischievous, Miss Chief is a supernatural being, a friend of humankind who questions and disrupts ways of thinking for the better good. She can choose any disguise or form, travel through time, and use her sexuality to disempower the colonizer. For Monkman, Miss Chief is part of the Cree worldview and broader Indigenous notions of the sacred.

Although he is an urban Indigenous person influenced by mainstream gay culture, Monkman situates Miss Chief not as a drag performer but as a Two Spirit figure grounded in Indigenous ways of knowing. His goal of challenging the accounts of Indigenous histories as told by colonizers is realized through the lens of Miss Chief. She becomes the narrator of her own imagined autobiography in which she can reverse the gaze of the colonizers by proposing an equally false history—one full of assumption, mischaracterization, and fetishization.

Residencies and Performances

In 2004, Monkman accepted an invitation for a weekend residency at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario. The opportunity came soon after a controversial dispute about the museum’s mandate between the McMichael’s board of directors and its founders Robert and Signe McMichael. The McMichael, billed as “the spiritual home of the Group of Seven,” was known for its conservative approach, embodying the canon of what the institution thought constituted Canadian identity through a focus on landscape. Contemporary art was not a priority. In addition, although the McMichael was one of the first museums to exhibit and collect contemporary Indigenous work, it separated pieces by leading artists such as Alex Janvier, Norval Morrisseau (1931–2007), Daphne Odjig (1919–2016), Carl Ray (1943–1978), Allen Sapp (1928–2015), and Bill Reid (1920–1998) from the rest of the collection.

During his residency, Monkman toured the First Peoples Gallery and came across the silent film In the Land of the Head Hunters, 1914, by the American photographer Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952), whose documentaries have been criticized for inaccurate portrayals of Indigenous life seen from the perspective of a colonizer. This film was a fictionalization of the world of Kwakwaka’wakw peoples of the Queen Charlotte Strait region of the central coast of British Columbia.

It was an opportune time for Miss Chief to intervene in Curtis’s story. She made her first physical appearance in the performance (2004) and film (2005) Group of Seven Inches, co-directed by and produced with Monkman’s long-time collaborator Gisèle Gordon. Echoing early Super 8 silent films, it stars Monkman as Miss Chief. Fashionably dressed in a feathered headdress, platform shoes, and a diaphanous breechcloth, she rides a horse into the grounds of the McMichael, encounters two white men dressed in moccasins and breechcloth, takes them into the Tom Thomson shack (a historic building on the property), dresses them in European costumes, and paints their portraits. Miss Chief effectively mocks the artists and diarists who were both fascinated by and exploitative of Indigenous peoples. Here, the white men act like well-behaved children and do everything that Miss Chief wants. The reversal is also evident in Miss Chief’s sexually charged identity, which displays both hyperfemininity and masculine authority.

In 2005, Monkman brought Miss Chief ’s performance Taxonomy of the European Male to Compton Verney, a museum in Warwickshire, England, for a group show co-curated by Cree art historian Richard William Hill. Miss Chief arrived at the museum on horseback and encountered Robin Hood and Friar Tuck along the way, both of whom she subsequently engaged in an archery match. Monkman referred to these performances as “Colonial Art Space Interventions.” With this work of performance art as well as Group of Seven Inches, Monkman drew on his early-career years when he worked in set and costume design.

Achieving National Recognition

The year 2004 was pivotal for Monkman: it was when the National Gallery of Canada purchased his work Portrait of the Artist as Hunter, 2002. Four years later, it would buy The Triumph of Mischief, 2007, a signature large-scale piece offering, in libidinous revelry, a glimpse into the history of Western art and the troubled interactions between First Nations peoples and Europeans. These purchases were official endorsements of the highest order. Other art museums, corporations, and collectors followed with major purchases; among these were the Royal Bank of Canada, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, and David Furnish and Elton John. As part of the 2008 renovation of the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, by architect Frank Gehry, Monkman was commissioned to do a work for the Canadian Galleries, then being curated by Gerald McMaster and David Moos. The result was The Academy, 2008, a painting in which Miss Chief appears wearing the bridal gown of Harriet Boulton Smith, whose gift of her art collection was critical to the establishment of the AGO. Monkman himself appears on the far right, wearing a Cree coat and speaking with the French Neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825).

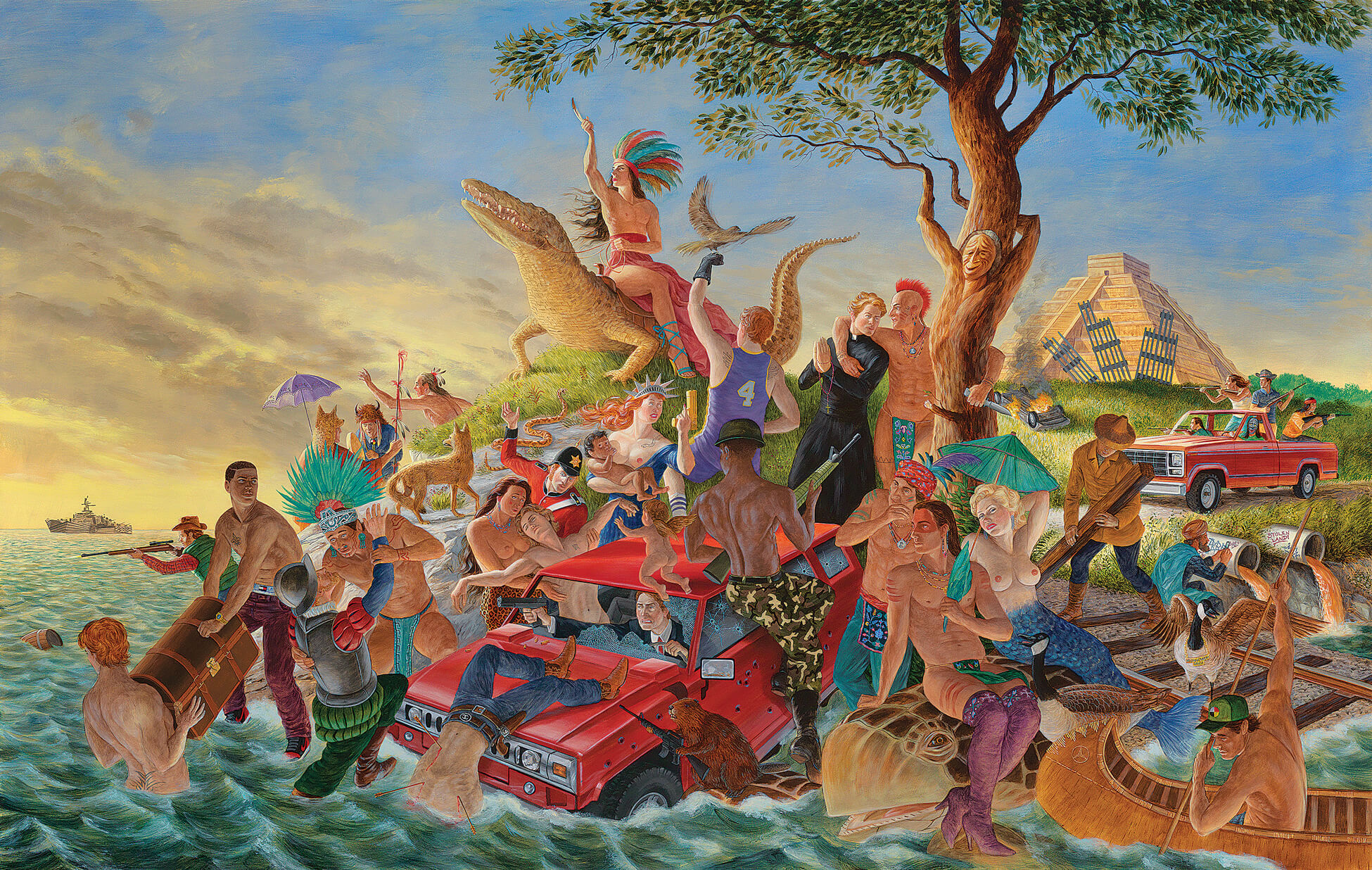

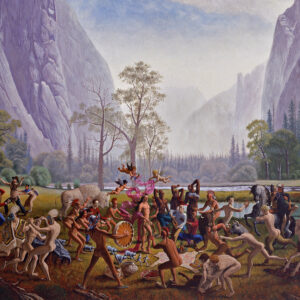

Monkman and Miss Chief Eagle Testickle were soon on their way to becoming famous figures in Canadian art with the power to undermine important institutional collections. In 2007, Monkman’s first major touring solo exhibition, The Triumph of Mischief, opened at the Art Gallery of Hamilton. The titular painting shows a setting that resembles Yosemite Valley and echoes the sublime Romanticist landscapes of Albert Bierstadt. The composition is conceptually similar to George Catlin’s Dance to the Berdash, 1835–37, but Monkman’s interpretation is subversively twisted and sexually charged. It includes artists, trappers, explorers, and mythical characters engaged in a wild gathering of homoeroticism, violence, and debauchery, all orchestrated around Miss Chief. Trappers of Men, 2006, is a similar work, one where power relations are played out in a landscape resembling Bierstadt’s Among the Sierra Nevada, California, 1868. In Monkman’s tableau, Miss Chief floats like the goddess in Birth of Venus, 1485–86, by Sandro Botticelli (1445–1510), amid an array of historical references to important art world figures.

As the exhibition circulated across Canada, Monkman travelled to each hosting museum and researched their collections. He would then produce a new work based on local histories and contexts; for the Winnipeg Art Gallery, for instance, he created Woe to Those Who Remember From Whence They Came, 2008. This method allowed for unprecedented adaptability, and it marked the beginning of his revisionist work in museum collections.

Prior to 2006, Monkman worked alone in a storefront studio on Christie Street in Toronto’s west end. As his reputation grew, so did the demands of exhibition invitations, residencies, and commissions. He struggled to balance his administrative duties with creating art. In 2008 he purchased a small factory building on Sterling Road in Toronto’s Junction Triangle, renovated it into a living and working space, and hired assistants to help with administrative and painting tasks.

Responding to European Art History

Though he first visited Europe when he was in his early 20s, beginning in the 2000s Monkman made a point of travelling there annually. His extensive research led him to connect with artists whose work ranged from history painting to modernism. At a time when he was standing on the cusp of global acclamation, these trips opened the door to new challenges and barriers to assail. What he discovered, in his words, was that “Europeans have no concept of Indigenous people…. they don’t know what colonization really means.”

Monkman had an epiphany during his only visit to the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid in June 2011. He was moved and “unexpectedly transported” by a Spanish history painting by Antonio Gisbert Pérez (1834–1901), Execution of Torrijos and His Companions on the Beach at Málaga, 1888. The quiet emotional resonance in a work that was politically charged intrigued him. “Over many years of looking at and studying great paintings, many have impressed me with their virtuosic technical achievements, but never had a painting reached across a century to pull me into the emotional core of a lived experience with such intensity,” he wrote.

Monkman realized that there were no history paintings that “conveyed or authorized Indigenous experience in the canon of art history.” This understanding subsequently led to a body of work in which he appropriates images from European masters or visual quotations from specific modernist artworks to unveil the true Indigenous experience. Miss America, 2012, for instance, refers to a fresco by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770), as does the later painting Miss Europe, 2016.

In 2014, Monkman enjoyed his first solo exhibition in Europe at the Musée départemental d’art contemporain de Rochechouart (now the Musée d’art contemporain de la Haute-Vienne) in France, located west of Limoges in what once was the Château de Rochechouart. Titled The Artist as Hunter, the exhibition featured paintings, photographs, prints, films, and several installations, including Miss Chief’s quiver, beaded moccasins, and assorted hunting gear in the château’s “hunt room,” which is adorned with sixteenth-century wall paintings of a stag hunt. Another installation in the show was The Collapsing of Time and Space in an Ever Expanding Universe, 2011, in which a melancholy Miss Chief is seen as an aging diva in her Paris apartment. It is presented in quintessential French château style, a rendition of affluent life frozen in time, echoing the natural history dioramas Monkman had encountered as a child at the Manitoba Museum, Winnipeg.

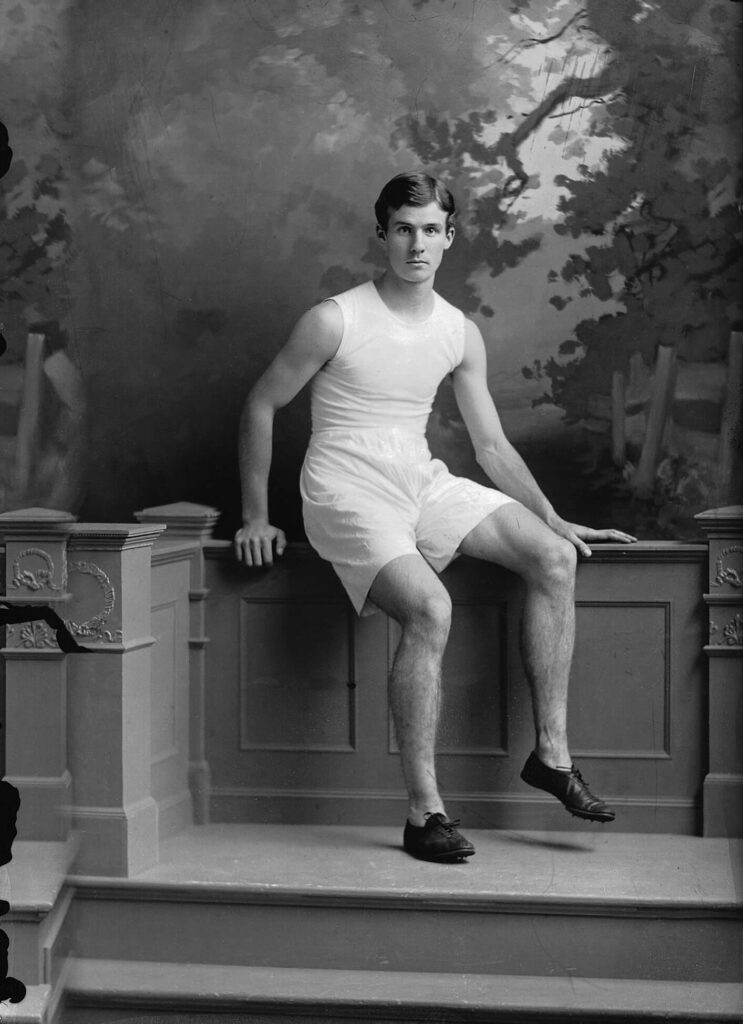

That same year, Monkman was invited to take part in the Artist-in-Residence program at the McCord Museum in Montreal, a place with holdings of the most comprehensive collection of archival prints by photographer William Notman (1826–1891). For his installation there, Monkman brought together two artistic legacies: the McCord’s archive of Notman’s photographs and The Painter’s Studio: A Real Allegory Summing Up Seven Years of My Artistic and Moral Life, 1854–55, a masterpiece by French artist Gustave Courbet (1819–1877). In his enormous canvas, Courbet surrounded himself with his muse, patrons, critics, and fellow artists—the summation of the social and economic ecosystem of art’s production. He was aware of the impending influence of photography, which supported his passion for realism. At the same moment in Canada, Notman was setting up his studio in Montreal, where he became known for innovative photographic techniques such as creating composites and setting up tableaux vivants wherein individuals and groups were posed in costume against theatrical backdrops.

Monkman’s curiosity about Courbet’s and Notman’s employment of photography and the medium’s impact on painting inspired him to set his scene in a tableau that quoted the works of both artists. Welcome to the Studio: An Allegory for Artistic Reflection and Transformation, 2014, is also a reflection of his own space and practice where his team works, and where curators, directors, funders, and collectors visit. Monkman strategically placed Indigenous peoples in the painting and positioned himself in the centre, thereby focusing on Indigeneity and satirizing historical practices expressed in the work of Notman and Courbet.

-

Gustave Courbet, The Painter’s Studio: A Real Allegory Summing Up Seven Years of My Artistic and Moral Life, 1854–55

Oil on canvas, 361 x 598 cmMusée d’Orsay, Paris

-

Kent Monkman, Welcome to the Studio: An Allegory for Artistic Reflection and Transformation, 2014

Acrylic on canvas, 180 x 730 cm

McCord Museum, Montreal -

William Notman, Capt. Huyshe, Montreal, QC, 1870, 1870

Silver salts on paper mounted on paper—albumen process, 17 x 12 cm

McCord Museum, Montreal

-

Kent Monkman, Welcome to the Studio: An Allegory for Artistic Reflection and Transformation (detail), 2014

Acrylic on canvas, 180 x 730 cm

McCord Museum, Montreal

Landmark Exhibitions

In 2015, Monkman received an invitation from Barbara Fischer, executive director and chief curator at the Art Museum of the University of Toronto, to curate a solo exhibition that would provide a critical response to the upcoming 2017 sesquicentennial of Canadian Confederation. At the time, significant events related to Indigenous rights and sovereignty were informing the work of cultural institutions and the work of artists, including Monkman.

On June 11, 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper, on behalf of the Government of Canada, delivered a formal apology in the House of Commons to former residential school students, their families, and Indigenous communities. Four years later, the Idle No More movement was established, and Treaty People in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta protested the Canadian government’s dismantling of environmental protection laws, an act that would endanger First Nations peoples who live on the land. In June 2015, the Resistance 150 movement was created by Anishinaabe traditional storyteller and teacher Isaac Murdoch, Métis visual artist Christi Belcourt (b.1966), Cree activist Tanya Kappo, and Métis author Maria Campbell. The group’s intention was to inspire Indigenous peoples to reclaim what was taken during colonization and to bring attention to climate change and resource extraction in Canada. The following year, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls was launched. Leading up to the Canada 150 celebrations, Indigenous activists planned counter-celebrations to challenge the commemoration of a history that ignores the tumultuous and traumatic relationship between Indigenous peoples and the rest of Canada.

Canada 150 also marked a critical period for museums as they began to move toward decolonizing by revisiting collections and making significant changes in policy. With the “reoccupation” protest on Parliament Hill in advance of Canada Day festivities in 2017, Indigenous activists succeeded in defining the sesquicentennial as an occasion to consider past harms and broken and unmet promises. Museums across the nation were responding to the Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, which included a section directed toward them.

After conducting extensive research into a dozen Canadian museums’ permanent collections, Monkman unveiled Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience at the Art Museum of the University of Toronto in January 2017. It was dedicated to his paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Monkman, “who like many of her generation,” Monkman wrote, “was shamed into silence in the face of extreme prejudice.” The title riffs on Jane Austen’s 1813 novel Pride and Prejudice, and the show was framed around Miss Chief’s trickster relations with colonizers. Pride is replaced with Shame to highlight Canada’s mistreatment of Indigenous peoples.

Experiencing the exhibition was compared to walking into a book. The installation consisted of nine “chapters” in which Miss Chief, via excerpts from her memoirs, reframed Canada’s foundational myths. In the first section, she was present in a life-size diorama titled Scent of a Beaver, 2016, dressed in lace and beaver fur and seated on a swing, evoking the work of French Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806). Attending to her were General Montcalm and General Wolfe, who led the French and British forces, respectively, at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759, the decisive conflict in which the latter’s victory led to Canada becoming part of the British Empire.

An adjacent work, The Massacre of the Innocents, 2015, set the tone for what was to come. Quoting the Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) painting of the same name from c.1610, the work depicts thirteen white and Métis settlers slaughtering beavers. In the exhibition narrative, Miss Chief spoke about the early politics that shaped Turtle Island and the fallout of colonialism. She told the story of what Monkman calls “the worst 150 years in Indigenous peoples’ history.” The exhibition challenged the nation’s interpretation of itself by telling the truth about the dark themes of colonialism while also sending a message of Indigenous resilience. It warranted two significant accolades for Monkman: the Ontario Premier’s Award for Excellence in the Arts and an honorary doctorate degree from OCAD University, Toronto.

In 2019, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art commissioned mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People), a diptych, as part of its series for contemporary projects responding to works in its collection. The work would be presented in the Great Hall, an imposing space with a conspicuous aura of cultural authority and achievement. By this time, fortuitously, Monkman had sold his studio and living quarters on Sterling Road in Toronto and purchased a building in North York, which he converted to a combined living and studio space big enough to take on large-scale projects and accommodate more assistants. In December 2019, he opened mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) at the Met. It consisted of two related, monumental paintings: Welcoming the Newcomers and Resurgence of the People.

For Monkman, the project represented the pinnacle of many years of work and served as an international showcase for his practice. He shared, “I’m very proud that I was given that opportunity and welcomed into the museum to speak candidly to their collection and to museum practices, which are on the edge of significant change. I think with these commissions the Met showed leadership in moving the conversation forward, further forward than some of the other institutions that are still lagging behind.”

The paintings illuminate how “encyclopedic” art museums perpetuate settler perspectives of history. The title mistikôsiwak derives from a Cree word meaning “wooden boat people.” It originally applied to French settlers, but Monkman uses it to refer to all the Europeans who colonized the so-called New World. The left painting of the diptych, Welcoming the Newcomers, dramatically recreates their arrival, as they brought with them institutions of religion and slavery. Resurgence of the People is a testament to, and celebration of, Indigenous resiliency. Both compositions teem with references to European and North American paintings and sculptures in the Met’s collections, with nods to European Old Masters such as Titian (c.1488–1576) and Rubens. Monkman’s paintings are particularly poignant in their references to works by Euro-American artists who depicted Indigenous subjects as noble and in a state of inevitable extinction. In 2020, the museum announced it had acquired the diptych for its permanent collection.

As the new decade began, the cultural landscape was changing profoundly in the wider world with #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, and a global pandemic opening up dialogue about injustice and inequality in radical new ways. Indigenous communities across Canada were angered by the 2018 acquittal of a white farmer in Saskatchewan who killed Colten Boushie, a young Cree man. A wave of uprisings against police violence and systemic racism took place after the killing of George Floyd, a Black man in Minneapolis who was murdered by police officer Derek Chauvin.

Among a younger generation of multidisciplinary Indigenous artists, including Meryl McMaster (b.1988), Duane Linklater (b.1976), and Tania Willard (b.1977), the reassessment of Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples has become even more pronounced. Several Black, Indigenous, and racialized artists, such as Deanna Bowen (b.1969), have joined in Monkman’s advocacy toward decolonization in art museums alongside curators such as Wanda Nanibush, Patricia Deadman, and Lisa Myers. Now a mature artist, Monkman continues to be a significant catalyst toward these shifts in the cultural landscape. His work and Miss Chief’s critical interventions are needed more than ever in the move forward to restitution. Believing that art can be a powerful force for social change, and inspired by Indigenous resistance and resilience, past and present, Monkman focuses on how to transform darkness to create a transcendent experience. With the ambitious goal to “decolonize Canada,” Miss Chief remains a force to be reckoned with.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements