Kazuo Nakamura was constantly experimenting with different styles, taking inspiration from Japanese woodcuts through Impressionism to the ideas of the Bauhaus. Although he was well known for his signature blue/green landscapes, those works were but one expression of his interest in nature. Ultimately, Nakamura was seeking a deeper truth in the numerical patterns and progressions that give structure to our universe. All of his art—whether figurative or abstract paintings, or sculptural works—was a means to a deeper understanding of the physical world we live in.

The Inspiration of Japanese Art

Early critics writing about Kazuo Nakamura’s work often commented, in passing, on its “Oriental” sensibility, as if that quality were self-evident. They referred to the delicate touch and sense of repose found in some of his paintings, and to their emphasis on nature. For the most part, these comments reflect a stereotypical and, at times, insensitive view that because Nakamura was of Japanese descent, by extension he would produce “Japanese art.”

George Elliott, writing about Nakamura’s work in 1954, was one of the first critics to draw the connection between the artist and Japanese art at length, stating: “He has two recognizable sources of subject-matter. One is what might be called a racial instinct for landscape. The traditional Japanese fragility, precision, simplicity, also a certain airy romance in landscape painting is in his work, although it is not especially Japanese in appearance.” Even the noted American critic Clement Greenberg, who was invited by Jock Macdonald (1897–1960) in 1957 to visit the studios of Painters Eleven, observed after seeing Nakamura’s work that the artist was “just a bit too captured by oriental ‘taste.’” This was not a compliment on Greenberg’s part, as he was notoriously anti-“Oriental” when it came to art.

Nakamura himself struggled with characterizations that his art reflected influences from Japanese culture. In a 1979 interview, Joan Murray posed the question:

Everyone notes that your work has something Japanese about it or Oriental at least. Were you actually thinking of Oriental art when you were working?

K.N. No.

J.M. Was it ingrown?

K.N. I think it must have been ingrown.

Only once did Nakamura explicitly acknowledge that a quality of his work might be directly related to a Japanese artistic sensibility. When asked about the well-known critic J. Russell Harper’s comment that a certain “Eastern Feeling” existed in Nakamura’s paintings, the artist replied: “If there is any Eastern feeling in my work, it may be my use of mono colour, which is also quite common now in many contemporary painters.” Works ranging from the Inner Structure paintings to the 1960s landscapes, such as Blue Reflections, B.C., 1964, as well as the String paintings, all show Nakamura’s use of single dominant colour hues.

Nakamura was aware early on—through his uncle and the Japanese art magazines he subscribed to—of the art being made in Japan. Yet his formal art education at Central Technical School and in the Toronto art scene exposed him to Western art, predominantly British. He may also simply have picked up on certain stylistic elements common to Japanese art through Western artists like Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), who admired and emulated nineteenth-century Japanese woodcuts.

In the broadest of terms, it might be argued that Nakamura embraced the notion of immersion in nature because of his exposure to this idea in Japanese art and culture. Art historian Richard Hill quotes this statement made by Nakamura: “Man is never above nature. Man is with nature (Universal Evolution).” That said, similar broad statements can be found in a number of sources, including the most obvious derived from science.

Setting aside the question of themes, one can easily apply to Nakamura’s work terms such as “refinement,” “harmony,” “stillness,” “precision,” “irregularity,” or “untutored beauty” (wabi-sabi), which have a long history in the art and aesthetics of Japanese culture. Some of Nakamura’s sculptures, like Tower Structures, 1967, can be characterized as unrefined, unfinished, and thus linked specifically to the Japanese aesthetic of imperfection. Then again, they can also be related to the Neoplatonic idea of the imperfection of earthly forms, as Jerrold Morris asserted when he spoke of Nakamura taking on the project of the Greek philosophers.

Some might argue that stylistic traits such as the high horizon lines and predominant blues in landscapes like August, Morning Reflections, 1961, can be attributed to Japanese influences. However, the high horizon is also a feature of the mountainous landscape around Tashme, British Columbia, where Nakamura was interned between 1942 and 1944, and consequently is seen in western Canadian landscape art too. Certainly there are traces of an influence, but they are incidental, picked up here and there, some more consistently applied than others.

In fact, Nakamura’s fullest statement about Japanese culture suggests why unravelling these influences is so difficult. In an interview with David Fujino, he was asked about Japanese culture and its survival in Canada. He said he felt that with intermarrying it would be diluted to the point that it would disappear in fifty years. He explained:

We think in terms of a Japanese population bringing its culture; but whatever is the strongest cultural influence will influence the rest of the general culture. At a certain point, you see, there’s a certain culture that fits into the evolution of the universal culture. It’s the strongest influence, so really it doesn’t have to be pushed or forced…. If you look at European culture you’ll notice that different cultures move into each other; for example, Greek became Roman culture.

Nakamura reflects this idea in his description of the evolution of art: in the charts he uses to outline the process, Japanese art is absorbed in favour of progress toward a more universal art.

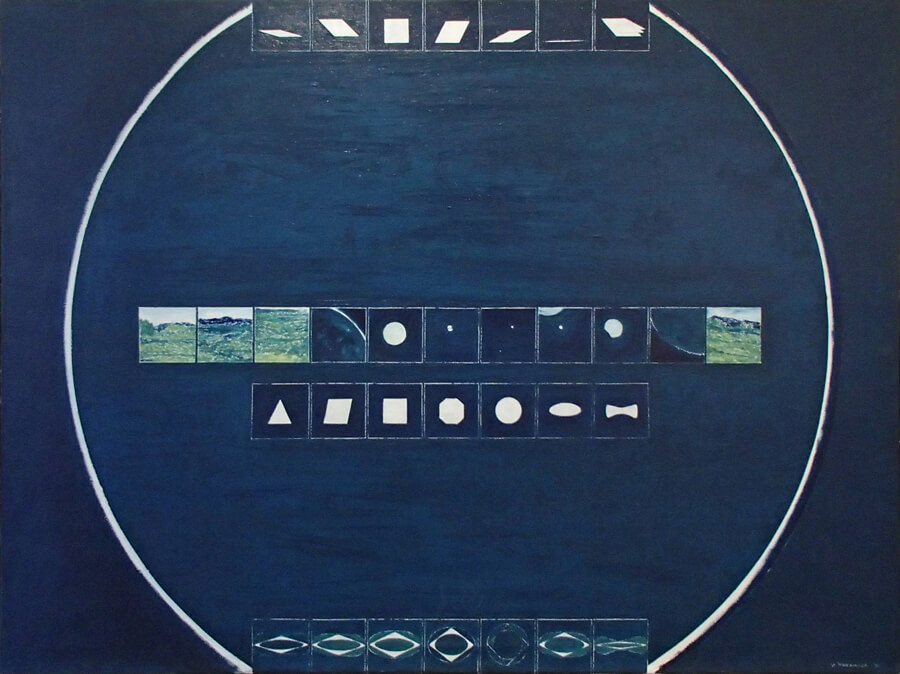

Perhaps because of this belief in a universal art, Nakamura was not interested in highlighting which elements in his work were Japanese and which were not. As Richard Hill has astutely recognized, Nakamura’s ongoing use of Prussian blue, as in Number Structure and Fractals, 1983, was a nod to Japanese indigo. However, to Nakamura this feature was not so much Japanese as it was universal: its origin may have been Japanese, but it had been folded into the universal culture for all to use. And as he strove to create more universal works with his Number Structure series, it became important not to show any discernable cultural influence. His concern, therefore, was not with the origin of an idea, style, or technique—Japanese or otherwise—but with applying it to our understanding of universal truths.

Impressionism and Post-Impressionism

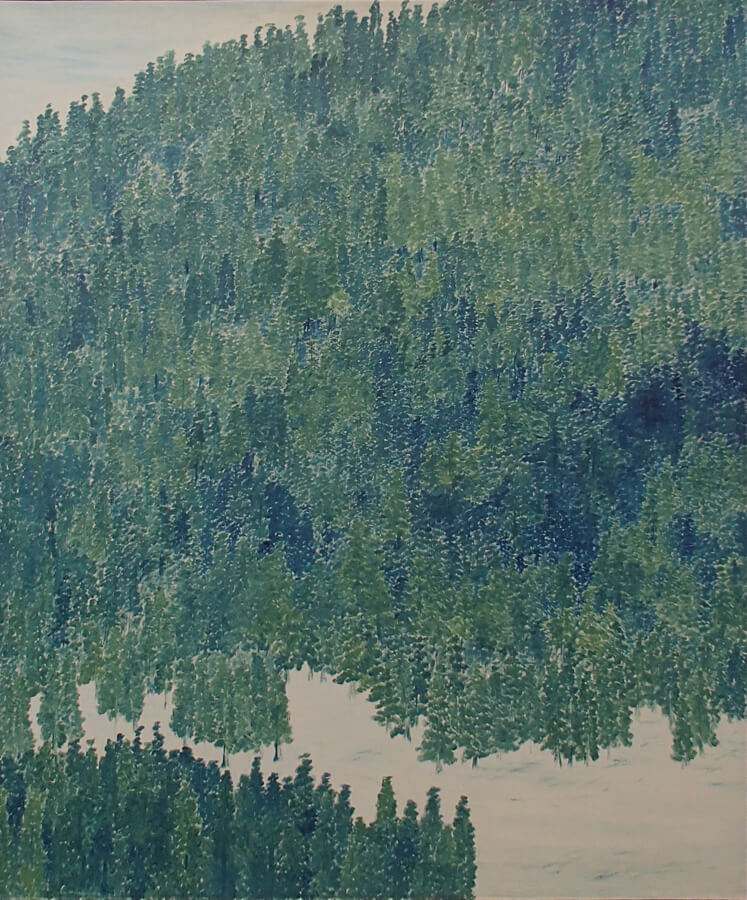

Both Impressionism and Post-Impressionism fascinated Kazuo Nakamura throughout his life, particularly the work of Claude Monet (1840–1926), Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), and Paul Cézanne (1839–1906). Cézanne appears to have influenced Nakamura’s paintings from the early 1950s, such as Forest, 1953. That painting’s broken brushwork, a technique adapted from the Impressionists, brings to mind the French artist’s early depictions of Mont Sainte-Victoire, which Nakamura saw in the February 25, 1952, issue of Life magazine. Along with a text on Cézanne’s work by Winthrop Sargeant is a pictorial essay that includes a Mont Sainte-Victoire painting dating from 1902–4. Another painting reproduced in the same article, The Little Bridge, 1879, depicts a lush forest with a bridge in the middle ground, all of which is reflected in the pool of water below. It bears a number of hallmarks also seen in Nakamura’s evolving style, including the high or absent horizon line, the broken brushwork, and the use of reflections. Additionally, Cézanne rarely used outlines to demarcate objects in his work, constructing his forms through colour, a practice Nakamura also employed.

Nakamura acknowledged Cézanne’s influence, pointing to a reproduction of Chestnut Trees at Jas de Bouffan, c.1885–86, in World Famous Paintings (1939) by Rockwell Kent (1882–1971), which was the first art book he purchased while interned at Tashme. The broken brushwork describing the ground beneath the trees and the network of lines created by the branches in that painting are features found in Nakamura’s work too. He also referenced Cézanne’s famous advice about dealing with nature through geometry, and then professed his desire to go a step further: “Cézanne broke nature down into cones, spheres. But we are living in an age where we can see a structure, a structure based on atomic structure and motion.” Nakamura’s Inner Structure works, which take up the themes of the atomic age, followed soon.

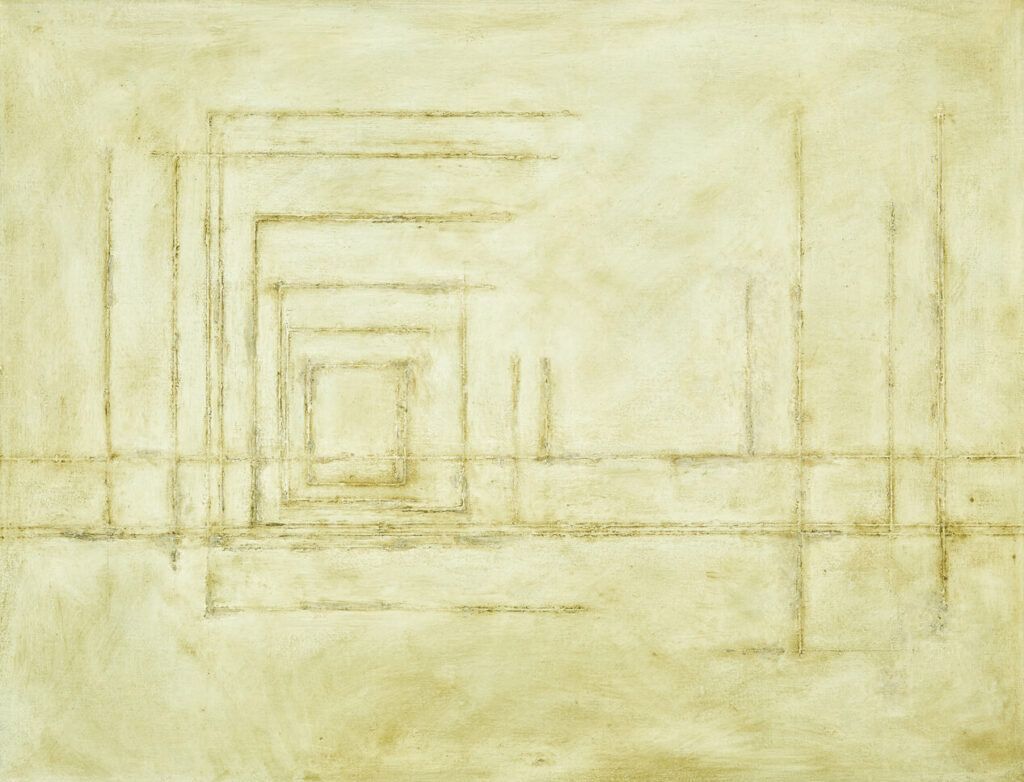

The mature style of paintings like Inner Structure, 1956, and Inner View, 1954, is indebted to Monet. It is a striking feature of these Inner Structure works that they appear somewhat hazy and out of focus, much like the atmospheric quality of Monet’s paintings of the Rouen Cathedral facade. It is Nakamura’s way of intentionally giving us but a glimpse of the underlying structure and patterns of the world. In his 1966 painting Green Landscape, a work that, uncharacteristically for his landscapes, includes a few red flowers—roses, to be exact—Nakamura appears to pay tribute to Monet’s Poppies, 1873, which he owned as a small reproduction. But generally, it was Monet’s later works—culminating with the Water Lilies series and their absence or near-absence of horizon lines, broken brushwork, and tantalizing play of light created through the use of white—that appealed to Nakamura.

Shortly after his nod to Monet with Green Landscape—and perhaps not coincidentally—Nakamura also paid tribute to van Gogh’s famous painting of irises in In Space, Blue Irises, 1967. Nakamura had a marked preference for blues and greens, two colours that predominate in van Gogh’s late oeuvre. As a collector of Japanese prints, in which green and blue are prominent, especially indigo in woodblock prints (aizuri-e), van Gogh may have been inspired to use these colours more frequently in his own work. Van Gogh also famously described the Japanese artist’s immersion in nature:

If we study Japanese art, we see a man who is undoubtedly wise, philosophic and intelligent, who spends his time doing what? In studying the distance between the earth and the moon? No. In studying Bismarck’s policy? No. He studies a single blade of grass.

But this blade of grass leads him to draw every plant and then the seasons, the wide aspects of the countryside, then animals, then the human figure. So he passes his life, and life is too short to do the whole.

Come now, isn’t it almost a true religion which these simple Japanese teach us, who live in nature as though they themselves were flowers?

Nakamura’s explicit tributes to Monet and van Gogh in the years 1966 and 1967 suggest he was looking at the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists at that time.

As he mapped out his theory of the evolution of art, Nakamura noted in an interview how it paralleled science’s development:

Around 1900 man started to understand about atoms; also then, the Impressionists appeared…. Until then, most art forms were quite lineal. But there’s no such thing as a line when you begin to understand atoms, and their motion. That’s one way you could say Impressionism came up. Then Einstein’s relativity theory is based on motion—and so is Abstract art and its forms.

Spatial Concept, Geometry of 1968 traces that evolution from the Renaissance to modern times with Impressionism and Post-Impressionism as the crux of a fundamental change. Reflecting that crux in his own work, Nakamura’s brushwork became looser, emphasizing an element of temporality related to motion, and he adopted a palette of blue/green hues that bordered on the monochromatic. And yet these were just two stylistic waypoints in his ongoing artistic evolution.

Bauhaus and Modernism

The fingerprints of the Bauhaus and modernism generally are all over Kazuo Nakamura’s body of work. Jock Macdonald, who tutored Nakamura as a teenager in Vancouver and was also a member of Painters Eleven, would have introduced these ideas initially, and Central Technical School of Toronto, whose curriculum and teachings owed a considerable debt to the Bauhaus, would have reinforced them.

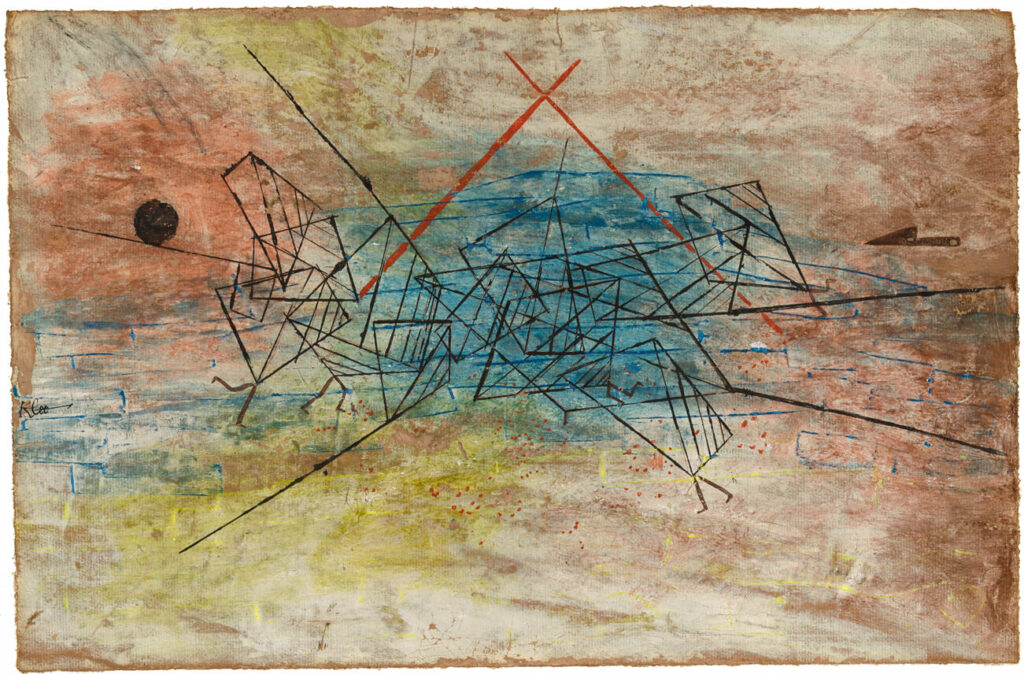

Macdonald likely drew Nakamura’s attention to the writings of László Moholy-Nagy, which address extensively the relationship between art, society, and science, and possibly also to the work and writings of Paul Klee, whose Pedagogical Sketchbook is replete with examples of scientific concepts informing his art. It is difficult to gauge the extent of Moholy-Nagy’s influence beyond the broad program that art’s progress must proceed hand in hand with that of science. His focus was more on technology and art, whereas Nakamura was more interested in the physical sciences. Klee’s writings deal with topics ranging from gravity to the motion of atoms, which Nakamura was equally interested in, but evidence of Nakamura having read Klee is scant. Occasionally, Klee’s use of colour washes and networks of spidery lines, as seen in Battle, 1930, are echoed in Nakamura’s work—Composition 10-51, 1951, for example.

The Bauhaus’s greatest influence on Nakamura was through its Bauhaus book series, edited by Moholy-Nagy, as well as its lectures. Through these sources, the school promulgated the modernist view of art by sharing the ideas of visiting artists and teachers to an audience beyond the school itself. Piet Mondrian’s collection of five essays, and particularly his “methodical evolution” from figurative painting to abstraction, clearly drew Nakamura’s attention. Not only was the initial work of both artists rooted in Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, but Mondrian and Nakamura also evolved a style that broke down our visible world into basic visual elements that were largely geometric. For example, Nakamura’s early use of trees and the way their branches evolve into an abstract network of lines that eventually merge with the space surrounding them, as in Hillside, 1954, matches closely the process Mondrian undertook in his famous tree series between 1908 and 1912. However, whereas Mondrian settled on a geometric simplicity heavily influenced by spiritualism, Nakamura pushed his abstraction further by embracing the mathematical devoid of any spiritual inflection. The Number Structure paintings are a clear example.

The notion of progress in the arts that Nakamura charted in Spatial Concept, Geometry, 1968, and described in various notes and short texts, was not new to the Bauhaus, but the school and many of the artists linked to it perpetuated the idea. Mondrian embraced the concept of art and society evolving toward a utopian goal, which in art meant greater visual simplification. It is an idea echoed in the writings and paintings of Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), whom Nakamura was familiar with, and Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935), whose work he would have encountered at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The geometric formulation of that evolutionary model, though, was more closely related to the Russian artist El Lissitzky (1890–1941), who famously paralleled the development of art with the history of mathematics in “A. and Pangeometry” of 1925. Lissitzky equated the two-dimensional, flat representation found in Egyptian art, for example, with a simple numerical progression of 1, 2, 3,…, and lines and planes in geometry. He cited mathematical equivalents for the introduction of overlapping forms and the use of fractions, and so on, until he reached the present (that is, 1925), where the art was equivalent to the emergence of imaginary numbers and non-Euclidean geometry. Nakamura’s reading is eerily similar, though it could have developed independently. In the 1974 publication for his Robert McLaughlin Gallery retrospective, Nakamura wrote:

1st tier: two dimensional perception concept—flat, ladder period (to about 1400 A.D.)

2nd tier: three dimensional perception concept—perspective and isometric period (1400–1870 A.D.)

3rd tier: four dimensional perception concept—cabinet, flat, octagonal, circle, concave-convex, mobius and wave period (1870 to present).

Broadly speaking, Nakamura saw art prior to 1400 as dominated by a two-dimensional conception of the world, then arriving with linear perspective at the Renaissance, and with Impressionism he saw a visual parallel to the world of the fourth dimension that includes non-Euclidean geometry.

The Bauhaus’s emphasis on the social function of art and its relationship to science and technology was critical for Nakamura both thematically and stylistically. By the 1960s he was experimenting with various forms of abstraction, especially geometric, in an attempt to capture and reveal motion not only in time, but also in space. That idea would guide his art for the rest of his life.

A Landscape Artist?

It is curious that in all the studies of Kazuo Nakamura, rarely is he identified and discussed as a landscape artist. Yet outside of his more abstract paintings, his sculptures, and the occasional still life, he produced nothing but landscapes. So why has he not found his place in the revered tradition of the landscape in Canadian art?

To start, Nakamura did not land on landscape painting by choice. His earliest paintings were of various locations around Vancouver, and it is only once he and his family were interned at Tashme that Nakamura started to draw and paint landscapes in earnest. In fact, some of the typical features of his landscapes, like the high horizon line, date back to his time at Tashme, as they were a feature of the geography of the area. It has also been suggested that Nakamura may have turned to landscape painting because he was never taught to draw the human figure when he studied commercial art. However, given his propensity to experiment, it seems more likely that Nakamura chose not to depict the human figure. People rarely appear in his paintings after 1945. And even in his sculptures, a medium that lends itself to portraiture, he stuck with abstract subject matter.

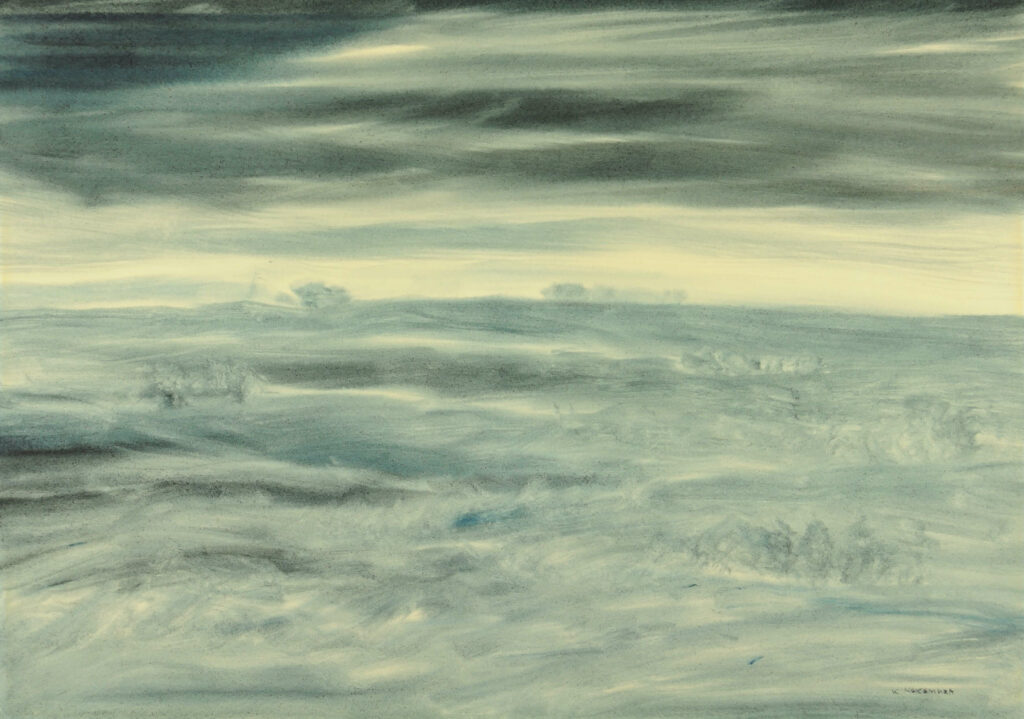

The question remains: Why is Nakamura so infrequently discussed in terms of the landscape genre? Most likely it is because he did not end up a landscape painter, but rather a painter of numerical sequences, an identity that he proudly accepted. Also, he never did settle on a single style. Tom Thomson (1877–1917) had a unique style, as did Paterson Ewen (1925–2002), when it came to landscapes: you cannot mistake their works as being by anyone else. Nakamura, in contrast, came to be identified with the exquisite blue/green landscapes he painted in the late 1950s and early 1960s, of which Lakeside, Summer Morning, 1961, is an excellent example. However, he produced those landscapes alongside abstruse works like Landscape 67, 1967. Moreover, the majority of his landscapes are naturalistic rather than realistic. In other words, they are not of an identifiable location, nor painted en plein air. For Nakamura, a landscape was an entry point to reveal more universal ideas.

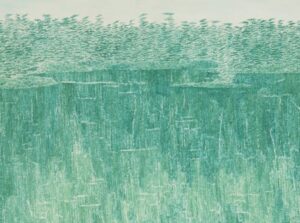

Nakamura liked to create landscapes depicting vast open spaces, lakes, and dense forests. Pictorially they mostly assert the flatness of the surface upon which the line and colours are applied, as he was keenly interested in pattern. Symbolically, the dense forests found in works like Hemlocks, 1957, provide a screen on which he creates intricate patterns with the branches and foliage, which reveal the order underlying the apparent chaos of nature. The open fields, as in Autumn Morning, 1958, show the vastness of the spaces we inhabit, ungraspable, which every now and then are concealed by fog or mist, making what lies beyond inaccessible as well. The lakes and their surfaces in Lakeside, Summer Morning contrast the physical world with their reflections, paralleling our own reflection of the world on the painted surface. Lastly, works like Landscape, 1953, border tantalizingly on abstraction, the end game of Nakamura’s career.

Perhaps most importantly, it is doubtful that Nakamura ever considered himself a landscape artist. He painted landscapes, but his purpose was never to represent the visible world. His goals were loftier. Every scene—whether tree, lake, mountain, or a mix—was an opportunity to experiment with a new way of seeing, to transcend the surface and find a new way to understand the structure that lay beneath.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements