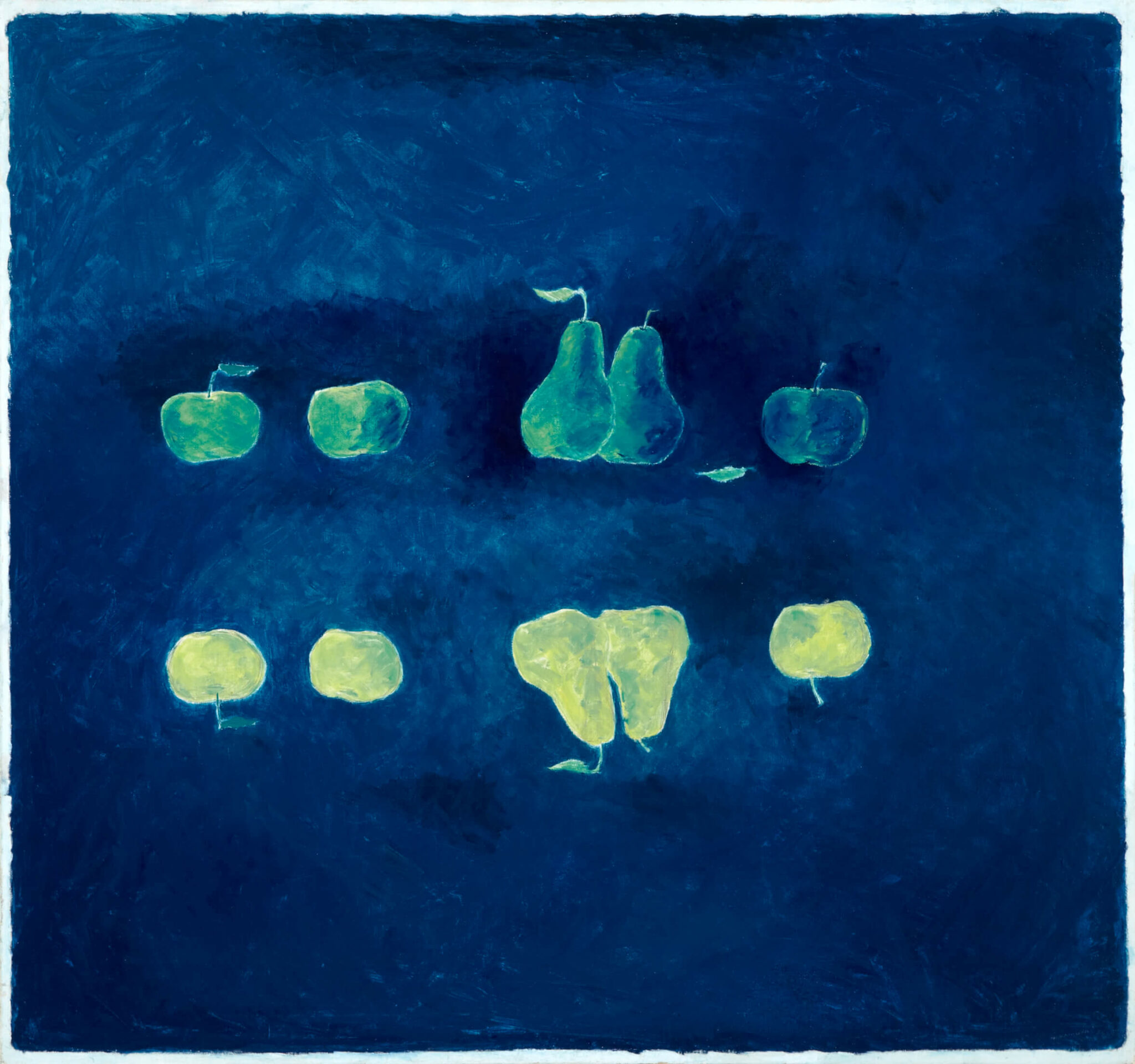

Reversed Images 1965

Kazuo Nakamura, Reversed Images, 1965

Oil on canvas, 81.3 x 86.4 cm

Private collection

Reversed Images portends Kazuo Nakamura’s late abstract works, which are marked by an exclusive use of geometry and mathematics. In this image of two green pears and three green apples laid out in a row against a dark blue background and mirrored immediately below, the artist is at a threshold pictorially. He looks retrospectively to his earlier landscapes and still lifes through works like Untitled, 1964, which duplicates and mirrors the potted tree in Autumn, c.1950. Here, the barrenness of the background with its deep blue coloration, the basic symmetry, the isolation of the figurative elements, and the patterned layout of the fruit distill what is to come in such works as Suspension 5, 1968, Spatial Concept, Geometry, 1968, and the Number Structure series.

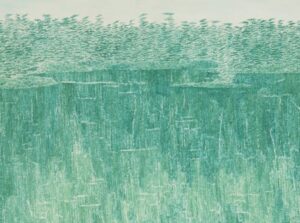

Many of Nakamura’s pieces have a mirroring element to them, whether in reflections off the water or in a doubling, as found in this painting. In nature, mirrors often distort; for example, the surface of water—most often when the water is still—can lengthen and bend reflections. The image we see is not real. Moreover, the water itself conceals. Nakamura’s lake views, which tend to be dominated by the water itself, suggest that he is reading the reflections this way. We are seeing but an imperfect glimpse of the underlying order of nature beneath the surface. Paintings like Reversed Images, where the focus is entirely on the mirroring that occurs, seem to confirm this. Here, he is peeling back the veil of nature to begin to expose its underpinnings.

What realities do Nakamura’s paintings hide? Reversed Images shows nature laid bare in the form of pears and apples, perhaps a nod to Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), who famously painted these fruits. Yet the painting conceals its mystery in the dark blue background. This blue screen can be read as either water or the night sky descending at dusk or lifting at dawn—or both, as the doubling of the fruit may suggest. We see the fruits of nature more clearly, but we do not yet see the patterns and progressions that gave rise to them.

In Japanese culture, mirrors symbolize the gods, most often Amaterasu, the goddess of the sun and the universe. Despite Nakamura’s lack of interest in spiritualism, he could not have been oblivious to that fact. More generally, the mirror in Japan is a symbol of truth and wisdom.

Mirrors are also a popular theme in science fiction, especially the notion of mirror universes or parallel universes. Nakamura may be referencing such an idea. He may also be touching on Noether’s theorem. In 1915 German mathematician Emmy Noether formalized a proof to show that the universe is composed of a series of fundamental symmetries in physics. For example, an action performed in one part of space will yield the same result in another part of space, a concept known as spatial translation. The pages of Scientific American, of which Nakamura was a voracious reader, were replete with mentions of symmetry in the 1950s and 1960s. Significantly, Nakamura saved an article from this magazine about the discovery of twin subatomic particles.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements