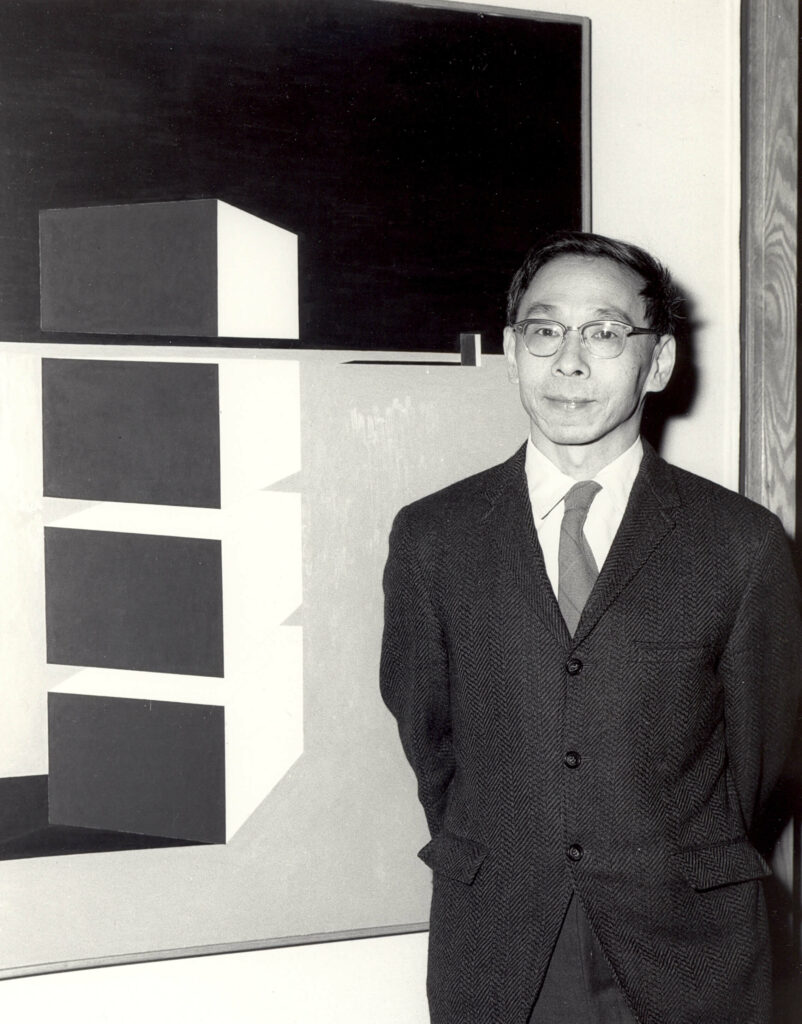

Kazuo Nakamura (1926–2002) produced one of the most varied, consistently original bodies of work of his generation. Born in Vancouver, interned as an “enemy alien” during the Second World War, and resettled in Ontario, he created paintings and sculptures over a career that spanned more than forty years. Inspired by his colleagues in Painters Eleven, he moved constantly between figuration and abstraction, experimenting with different styles and techniques as he sought to reveal the universal laws of nature found in science and mathematics. During his lifetime, Nakamura achieved a level of success that was virtually unprecedented for any Japanese Canadian artist. He opened doors for a new generation of artists today.

The Early Years

Kazuo Nakamura was born on October 13, 1926. He was a second-generation Japanese Canadian (nisei). His father, Toichi Nakamura, had moved to Canada from Hiroshima in February 1911 at the age of fifteen, accompanying his own father who had made the trip at least a couple of times before. Although the elder Nakamura returned to Japan after a few years, Toichi settled in Vancouver in the neighbourhood known as Japantown or Little Tokyo, which was at the time a largely self-sufficient community where many immigrants from Japan lived.

Like so many of his compatriots, Kazuo’s father was seeking a better life in North America. Rapid urbanization in Japan in the late 1800s had deepened economic problems there. Many Canadians, however, saw the influx of Asian immigrants into Canada, and specifically into British Columbia, as an economic and social threat. By September 1907 underlying anti-immigration and racist attitudes against Asians by whites reached a boil, and riots broke out in Vancouver’s Chinatown and Japantown. Several government agreements subsequently restricted the number of Japanese immigrants permitted into Canada between 1908 and 1928.

Toichi Nakamura worked at a variety of jobs until he and his brother opened a restaurant in Japantown. In 1923 he travelled back to Hiroshima to marry Yoshiyo Uyemoto; he returned to Vancouver with his bride that same year. In 1925 the first of five children (three sons and two daughters) was born; Kazuo was the second child. The Depression forced the family to close the restaurant in 1935, and they moved out of Little Tokyo, heading south to 23rd and Main Street. There they opened a dry-cleaning and dressmaking shop, living in cramped quarters behind it, and integrated quickly into what was a relatively diverse community.

As a youth Kazuo Nakamura appears to have savoured life in the city. His earliest paintings depict landmarks like the Army & Navy discount department store on East Hastings Street, which appears in First Frost, 1941, as well as the Cambie Street Bridge and views of Main Street.

Nakamura received his first art training after he completed grade school in 1939. At Vancouver Technical Secondary School, he enrolled in the applied arts program, where he studied drafting, mechanical drawing, and design. Noted modern artist Jock Macdonald (1897–1960) was teaching at the school, and it is believed that Macdonald taught Nakamura design and tutored him at least once a week in drawing and painting in 1940 and early 1941, and possibly into 1942. The young artist also perused the art books of his uncle Shusaku Nakamura, who was an amateur painter. Of particular interest to Kazuo were the reproductions of French Impressionist paintings, as well as works illustrated in the Japanese art magazines his uncle subscribed to. Nakamura obtained his art supplies by way of the Simpson’s and Eaton’s mail-order catalogues.

Early work by Nakamura depicts its subject matter in a matter-of-fact, measured way, rarely displaying any flourishes that might be mistaken for self-expression. This may be because Nakamura was learning the craft or because of his unconventional training for an artist. Yet this detached quality is found in much of his subsequent work. People rarely appear in his art. In only a handful of early examples do we find figures, and they seem incidental to the scene.

Nakamura often claimed to have been a self-taught artist, possibly because his formal training was in drafting and design. The city landmarks that appear among his first works likely provided the settings Nakamura needed to practise linear perspective. He related that his younger brother, Yukio, was learning the technique in art class at John Oliver High School and taught him the rudiments of using gridlines and lines converging at a vanishing point to create depth on a flat surface. Nakamura eventually translated these lessons to his landscape paintings, which he began to make as an adolescent and continued for the rest of his career. For example, he uses the rows of strawberries in Strawberry Farm, c.1941, as parallel lines (orthogonals) that establish the perspective. The draftsman’s grid (or net) and linear perspective likely piqued his interest in geometry as a tool for representing and understanding nature.

When or how Nakamura was first drawn to the sciences that played such a pivotal role throughout his life is difficult to determine. Some have suggested that Jock Macdonald may have inspired Nakamura, since Macdonald was interested in exploring science to understand the underlying principles of nature. However, Nakamura did not seem to share an interest in the spiritual dimension that informed Macdonald’s Etheric Form, 1936 (dated 1934), and other works. Perhaps Nakamura chose the applied arts over a fine arts education because he saw it as an ideal compromise between art and science. On this subject, Nakamura noted in a 1993 interview, “Because of the war, and being interned, I lost time, and decided not to become a professional scientist, but to go into art.”

The Second World War and the Internment of Japanese Canadians

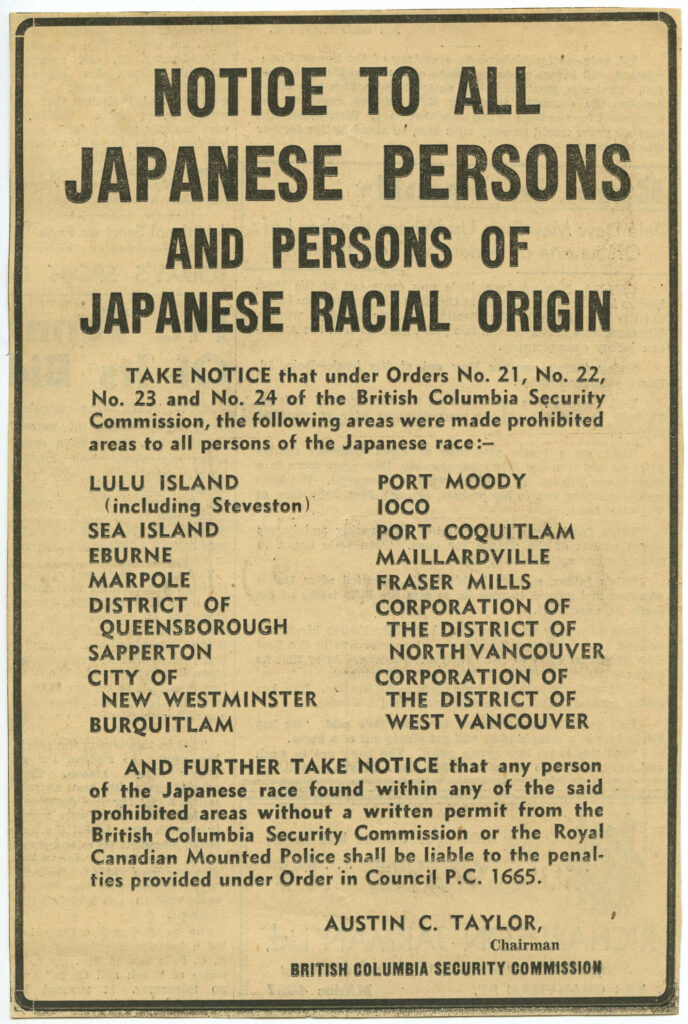

Kazuo Nakamura’s life was changed with Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and its invasion of Britain’s Hong Kong colony on December 7, 1941. Canada’s Prime Minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King, declared war on Japan that same evening. The official proclamation came the next day. These events reignited the festering anti–East Asian racism in British Columbia, a feeling that the Liberal MP for Vancouver Centre Ian Alistair Mackenzie captured succinctly when he said in April 1942: “Let our slogan be for British Columbia: ‘No Japs from the Rockies to the seas.’” Mackenzie played a key role in driving King’s response to what was referred to as “the Japanese problem.” On December 16 the Canadian government, under considerable pressure from the provincial government of British Columbia, required all people of Japanese descent to register with the Registrar of Enemy Aliens.

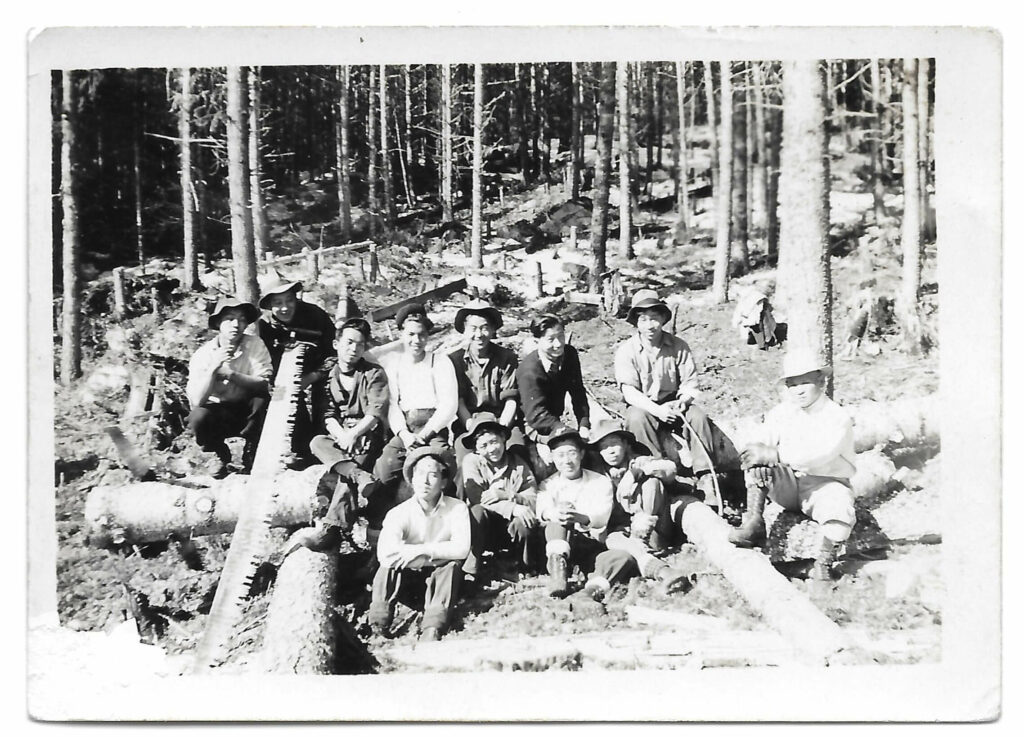

In January 1942 King invoked the War Measures Act to require “persons of Japanese racial origin” living on the west coast to relocate to a “protected area” 160 kilometres inland. Until the internment camps could be built, many Japanese Canadians were held in the livestock barns on the Pacific National Exhibition grounds in Hastings Park, where the sanitary conditions were terrible and there was little if any privacy. Most were moved to camps within a few months (where in some instances Japanese Canadians were required to build their own shelters), but it took up to eighteen months before all people of Japanese origin were transported to the eight internment camps in B.C. and the labour camps scattered across the country, where many adult men were separated from their families and sent to work.

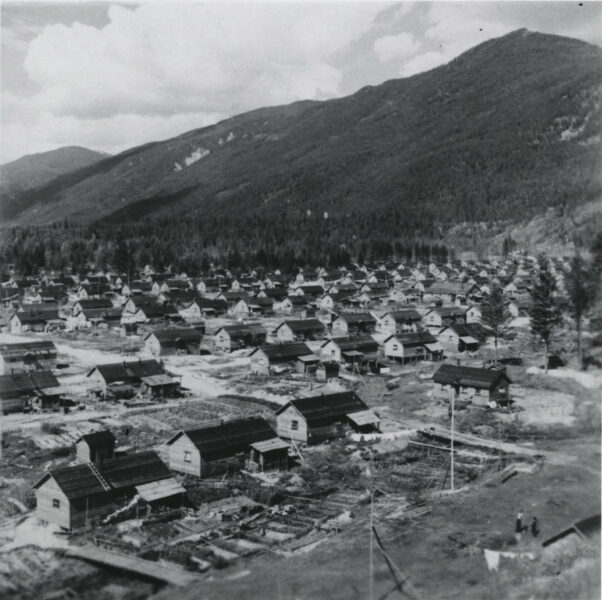

Nakamura’s family did not suffer the indignity of the livestock barns, likely because they were not living in Japantown where the high concentration of Japanese Canadians was perceived as a threat. The Nakamuras were subject to a curfew, but they remained in their home until October 15, 1942, when they were relocated to the camp in Tashme, a small community twenty-two kilometres east of Hope, a town in the Fraser Valley at the confluence of the Fraser and Coquihalla Rivers. Among the last to arrive in Tashme, Nakamura and his family were assigned to a cabin on the last of the ten rows of avenues at the camp.

In total, around 22,000 Japanese Canadians were forcibly removed from their homes to the camps, which were known as “ghost towns.” The land and property they left behind was confiscated and later sold at auction by the Canadian government without the owners’ consent, purportedly to pay for the construction and maintenance of the camps. The housing provided was flimsy at best, without plumbing or electricity, and wholly inadequate for the winter months. In many cases the internees had to repair and heat their shelters with timber from the surrounding forests. And unlike in the United States, the Canadian government supplied no food or clothing, so families were left to farm their own food and acquire any other supplies they needed using their savings and charitable donations.

At Tashme, Nakamura worked during the day, mostly cutting lumber and clearing brush. In the evenings he attended high school classes given by Christian groups, because the Canadian government provided only elementary schooling in the camps. He continued with his art practice, purchasing his art supplies through the Simpson’s and Eaton’s catalogues and dedicating every free moment to sketching and painting. He even managed to acquire art books, most notably World Famous Paintings, the 1939 book by Rockwell Kent (1882–1971), and was particularly struck by the works of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), Grant Wood (1891–1942), and Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847–1917). Art was an essential escape from the hardships of the camp, and he painted Vancouver street scenes from memory to hold on to the hope of returning home. As he said years later, “We thought we would go back.”

-

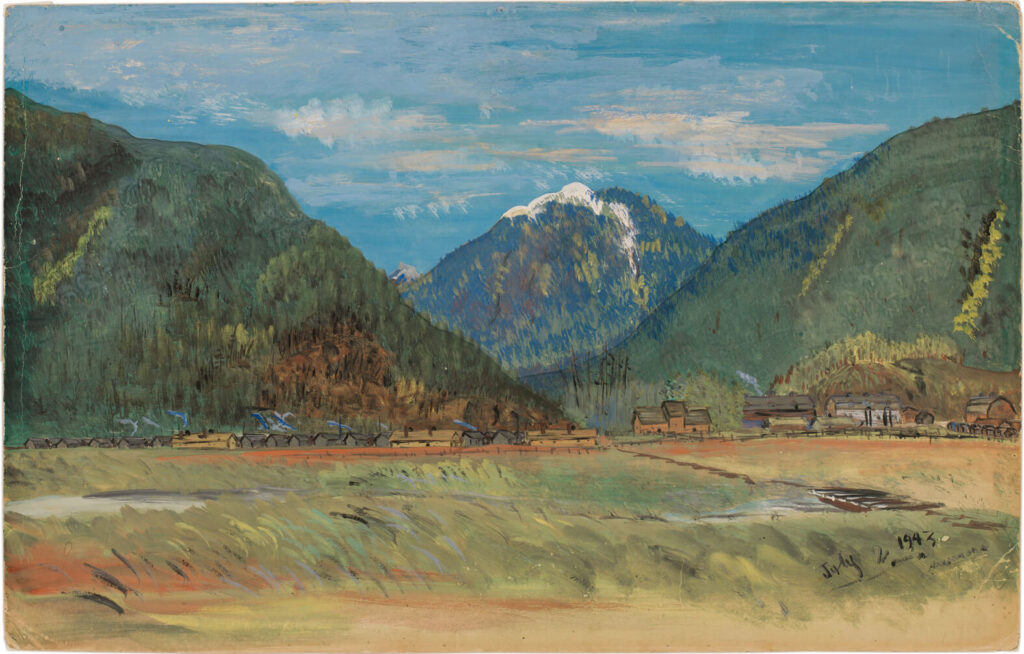

Kazuo Nakamura, Tashme at Dusk, July/August 1944, 1944

Oil on board, 34.6 x 53 cm

Private collection -

Tashme camp, c.1940–49

Photographer unknown

Japanese Canadian Research Collection, University of British Columbia Library, Rare Books and Special Collections -

Kazuo Nakamura, Night Class, 1944

Watercolour and graphite on paper, 22 x 30 cm

Canadian War Museum, Ottawa -

Building L, School (Formerly Winter Garden), Hastings Park, Vancouver, c.1942

Photograph by Leonard Frank

Alex Eastwood Collection, Nikkei National Museum Burnaby -

Kazuo Nakamura, Torch Parade, February 25, 1944

Watercolour on paper, 23 x 30.6 cm

Canadian War Museum, Ottawa -

View of Tashme Camp, c.1940–49

Photographer unknown

Japanese Canadian Research Collection, University of British Columbia, Rare Books and Special Collections

Nakamura said little publicly about what he was thinking or feeling, and it is hard to tell from his paintings. Tashme at Dusk, July/August 1944, 1944, appears to be a straightforward depiction of the landscape. He painted mostly nighttime scenes, which is unsurprising given that he had free time only in the evenings. Although the camp buildings gave Nakamura some reference points for his study of perspective, the nearby forests, mountains, and lakes offered new subject matter and challenges. The open areas in Twelve Mile Lake, 1944, provide few sightlines to construct the space; when this is combined with the dense screen of the forest and the high horizon line, applying linear perspective becomes onerous. Few scenes painted at this time include people, except Night Class, 1944, which may be one of the last paintings he completed at Tashme.

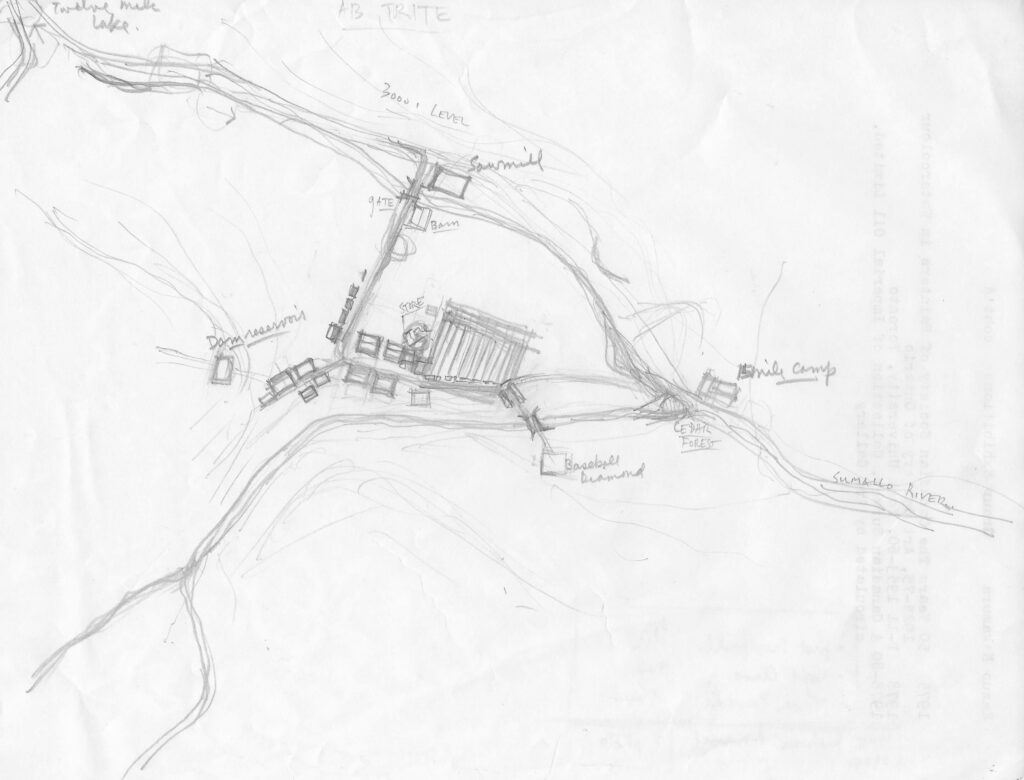

Nakamura’s paintings from Tashme laid the foundation for his mature work. Here lie the roots of the landscapes and patterns that characterize all of his work. When asked later about his internment, Nakamura claimed: “It didn’t affect me much.” Yet the dates his family arrived and left the camp were indelibly seared into his memory. He attended the fiftieth anniversary reunion of the opening of the internment camp, held in Toronto. And in his papers at the time of his death was a sketch of the layout of the camp. Tashme and the works he produced there likely launched Nakamura on his search for meaning in the universe and the underlying order of nature. Maybe it is not surprising that the meaning he found excluded human nature.

Heading East: New Beginnings and Early Success

During the latter half of 1943 and the beginning of 1944, a growing sentiment in favour of the interned Japanese Canadians emerged in King’s cabinet, fuelled by legal protection south of the border for the rights of Japanese Americans and changing public opinion in Canada. Even so, strong anti-Japanese feelings continued in British Columbia. On August 4, 1944, the federal and provincial governments reached a compromise, and the process of releasing Japanese Canadians from the camps soon started in earnest. The Canadian government gave internees two options: to be deported to Japan at the conclusion of the war or to relocate east of the Rocky Mountains. Going back to the homes they had left behind in British Columbia was not a choice. Instead, many families were forcibly sent to Japan, where they found a country badly ravaged by the war. Returning to Japan was never an option the Nakamuras considered, however, as they were Canadians.

A slow trickle of Japanese Canadians had begun to leave the camps as early as 1942 to supplement the Canadian labour force supporting the war effort. Kazuo Nakamura’s older brother, Mikio, left Tashme in the spring of 1944 for Toronto, where he settled and found a job. Kazuo and his father intended to join Mikio there, with the rest of the family following when the men had found accommodations and earned some money. Accordingly, Kazuo left Tashme with his father on November 25, 1944. But they found that Toronto had met its government-assigned quota of Japanese Canadians. They settled in nearby Hamilton instead, and the remaining members of the family joined them in March 1945.

Just four months later, on August 6, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, levelling the city, immediately killing around 75,000 people and injuring another 70,000. The radiation from the bomb would lead to further deaths over time from cancer. Among those killed when the bomb detonated were some of Nakamura’s relatives. A second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki on August 9, killing an estimated 40,000 more people and injuring 25,000 others. On August 10, the Emperor of Japan saw there was no choice but to surrender to the Allies. He made the official announcement on August 15. In an interview late in his career, Nakamura was asked how the bombing affected him. He responded: “The good thing is it made the Japanese surrender.” He did not speak publicly about this time, but an article from the Toronto Star of August 6, 1995, marking the fiftieth anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima was found among his papers at the time of his death.

Once settled in Hamilton, nineteen-year-old Nakamura found a job as a semi-skilled labourer at Kraft Containers Ltd., a box factory. He continued to paint in his spare time, producing works like Nightfall, Hamilton, 1945, and later recalled that the first book he bought in Hamilton was a volume on Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890). He enrolled in a painting class in the evening at the Hamilton Technical School, and around this time he decided on a career in commercial art. To that end, he moved to Toronto in August 1947 and worked for a year at a sheet-metal shop. But soon, as Nakamura put it, “I decided there were easier ways of making a living.”

Nakamura began his formal art training in Toronto in 1948, enrolling as a student in the Art Department of Central Technical School (CTS). The vocational high school was well regarded for its excellent adult education programs and its art department, which had graduated four members of the Group of Seven. Among its faculty at the time Nakamura joined was Doris McCarthy (1910–2010), who was his landscape painting instructor. When asked what he learned at CTS, Nakamura related to art historian Joan Murray: “As far as the school goes it’s a case of learning to draw. I think that was the main thing . . . drawing from a still life or from a life study.”

He also acknowledged that the director of the art department, Peter Haworth (1889–1986), had made an impression on him. Given Haworth’s enthusiasm for the Bauhaus and its combination of crafts and fine arts, he may have shared some of its leading principles and ideas with Nakamura. An English translation of New Vision by the Bauhaus master László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946) had just been published in 1947, followed by a new work, Vision in Motion, which expanded on the ideas in the first book. Moholy-Nagy’s emphasis on the importance of modern technology, the need for art and science to work in harmony, and his discussions of the work of Paul Cézanne and Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) would have caught Nakamura’s attention.

Also of interest was the work of British painters Ben Nicholson (1894–1982), Matthew Smith (1879–1959), and Paul Nash (1889–1946). A good number of the CTS instructors were British or educated within a British tradition. As well, major Canadian art galleries of the 1940s and 1950s were collecting art by British painters, and thus this art was frequently exhibited and written about. For his part, Nakamura appreciated Nicholson for his skill in design, Smith for colour, and Nash for his draftsmanship.

Nakamura’s own work from this period continued in the vein of the cityscapes he had painted in Vancouver and from memory in Tashme. Many were done at night, such as Evening Shadow, 1949. His colours were more varied and a little richer, likely reflecting his ability to purchase more supplies than he could afford at Tashme. Landscapes, though, predominate, with numerous pictures of the open spaces north of Toronto, as can be seen in Winter, Don River, 1949.

In addition to his formal studies, Nakamura took night classes taught by Albert Franck (1899–1973), who touted him as an aspiring artist and invited him to join the legendary gatherings of artists that he and his wife, Florence Vale, hosted in their Gerrard Street Village home. It was during those evenings that Nakamura first met Oscar Cahén (1916–1956), Harold Town (1924–1990), Walter Yarwood (1917–1996), and Ray Mead (1921–1998), all future members of Painters Eleven. They, in turn, initiated him into the Toronto art scene.

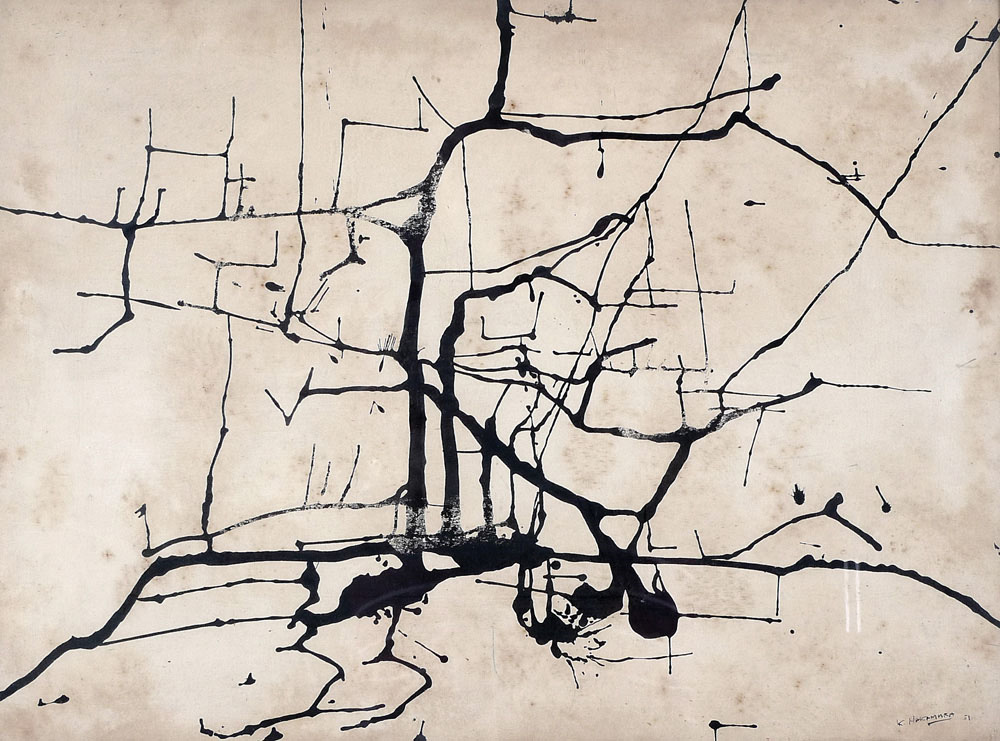

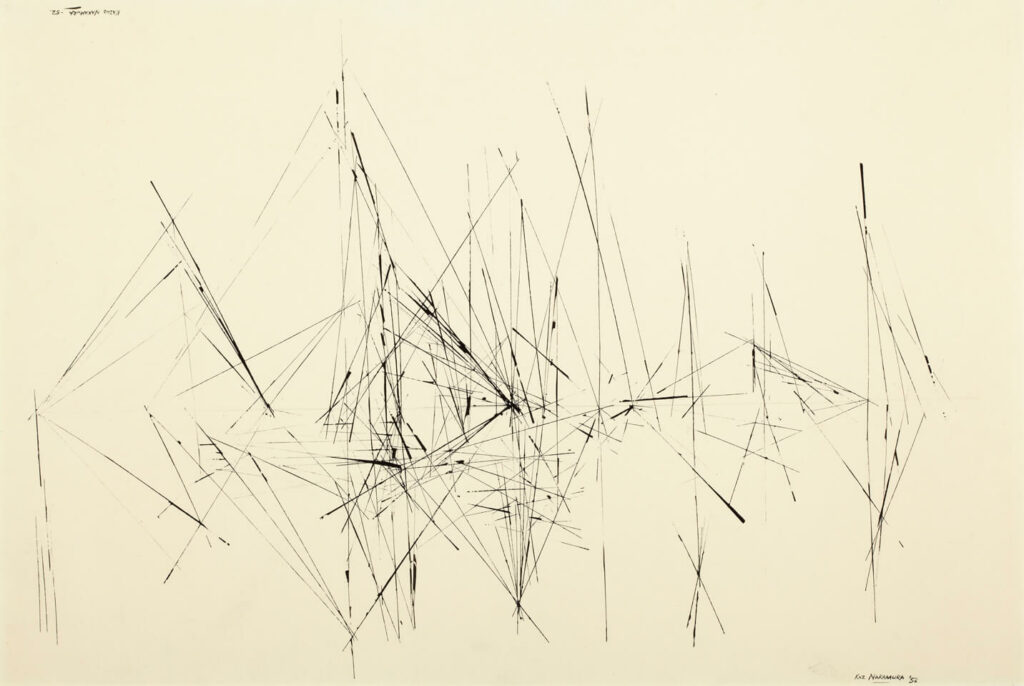

Nakamura’s new friends inspired him to begin experimenting with his art. Some of his city views and landscapes began to take on a more ethereal, atmospheric look, with Composition 10-51, 1951, showing a series of bridges and electrical power lines as a network of lines emerging through a fog or morning mist. In Landscape, 1952, the horizontal format and concentration of forms and lines in the lower half are, with the title, the only hints of a landscape as the subject of this work. In both works Nakamura begins to seriously toy with abstraction.

Franck, with R.F. Valkenberg, also organized the first public show in which Nakamura’s work appeared. In 1950 two of Nakamura’s paintings, Noon Shadows, c.1950, and Red Stools, c.1950, were shown at the inaugural Unaffiliated Artists show at Eaton’s College Street store alongside works by Town and Cahén. Nakamura showed again at Unaffiliated Artists the following year. His work Beach Statue, n.d., was then included in the Canadian Society of Painters in Water Colour exhibition, and he joined that society shortly after—an opportunity that likely came about through Jock Macdonald, who became the president of the society in 1952. It was also in 1951 that Nakamura graduated from Central Technical School.

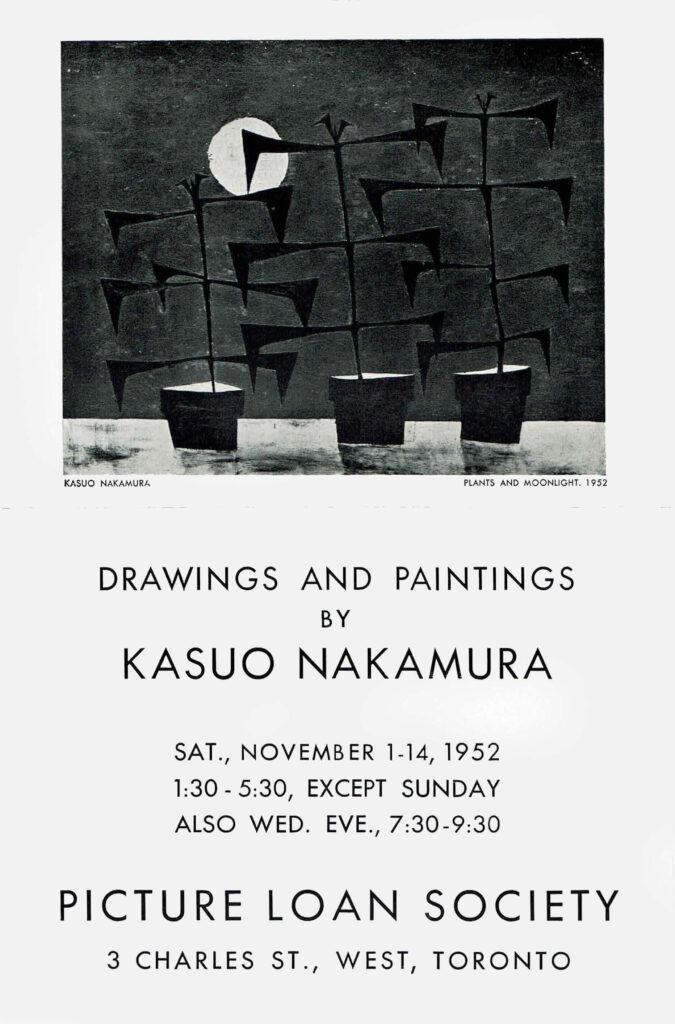

In 1952 Nakamura showed two new works, Distant Valley, 1952, and Swamp Land, 1952, in an exhibition hosted by the Canadian Society of Graphic Art. However, the highlight of that year was Nakamura’s first solo exhibition, held November 1–14 at the Picture Loan Society. Douglas Duncan (1902–1968), the founder and director of the society, started to show an interest in the emerging artists of the Toronto art scene in the early 1950s and hosted the first solo exhibitions for Nakamura, Harold Town, and Alexandra Luke (1901–1967). The Picture Loan Society exhibition was an impressive achievement for an artist who was just one year out of school. And just a year later, Hart House at the University of Toronto hosted Nakamura’s second solo exhibition, which may have been secured by Macdonald.

In less than ten years, then, Nakamura had gone from “enemy alien” to celebrated emerging artist. Franck’s backing as well as Macdonald’s support and the resulting friendships opened many doors for the young artist. And he arrived in Toronto as a generation of artists was breaking down barriers in art, gender, and race. In particular, details were emerging about the harsh treatment and human rights violations that Japanese Canadians had endured during the Second World War. Social and political changes were creating new opportunities, and the postwar Toronto art scene nurtured Nakamura’s talent and the talent of many young Japanese Canadian artists and architects, including Stan Shikatani (b.1928), Aiko Suzuki (1937–2005), Takao Tanabe (b.1926), and Raymond Moriyama (b.1929).

Painters Eleven and Critical Achievements

The 1950s elevated Kazuo Nakamura to one of Canada’s elite artists, or at the very least one of its most innovative. The successes he accrued shortly after graduating from Central Technical School continued, and he gradually ascended to national and then international attention by the end of the decade.

In October 1953, Nakamura participated in the Abstracts at Home exhibition organized by William Ronald (1926–1998) and Carry Cardell and held in the furniture department at Simpson’s in Toronto. It featured the work of seven artists—Ronald, Alexandra Luke, Oscar Cahén, Jack Bush (1907–1977), Tom Hodgson (1924–2006), Ray Mead, and Nakamura—whose works were shown in different home-like settings. Ronald had worked as a designer for Simpson’s, and the idea of showing radical art in a department store perfectly embodied “making the complacent living rooms of Toronto safe for abstract art”—a goal that would be critical to Painters Eleven, the group these artists would soon establish. Cardell, a Dutch artist trained in Bauhaus-influenced institutions in Amsterdam and The Hague, was friends with Jock Macdonald from when they were both teaching in Calgary, and she had a hand in the furniture settings.

Although the exhibition was titled Abstracts at Home, the four pieces Nakamura contributed were landscapes. Morning Landscape, 1953, for example, was likely included in the show because it bordered on the abstract like some of his other figurative work at the time. Nakamura’s display for the exhibition included three paintings, one above the other, against a “grass wallpaper,” with a low and wide coffee table below and two cushions on the ground. It was clearly meant to suggest an “Oriental” setting. To further suggest the works’ fit in the modern home, an advertisement for Abstracts at Home in the Globe and Mail listed each room’s contents with their associated prices.

Unfortunately, the reception of Abstracts at Home did not match expectations. The idea that showing contemporary art in a “home” setting in a department store might appeal to the middle-class consumer did not translate into sales. As Nakamura succinctly noted, “It didn’t communicate to the average person.” Nor did the exhibition draw any critical attention—there is no record of any reviews. Nevertheless, the seven artists got together for publicity shots and then met up again at Ronald’s studio, where they decided to form a group that would exhibit their abstract art for Toronto audiences.

An expanded group met at Luke’s cottage in Oshawa a few weeks later and at this meeting formed Painters Eleven. Ronald brought Macdonald, Mead asked Hortense Gordon (1886–1961), and Cahén invited two of his advertising friends, Walter Yarwood and Harold Town. The name of the group simply reflected the number of members and their artistic medium. Although their first show, which featured the work of Jack Bush and opened in February 1954 at Toronto’s Roberts Gallery, drew large audiences, there were few sales. This outcome was not atypical for any groundbreaking exhibition. Nevertheless, the public was officially introduced to “the first rat pack of Toronto modernism.”

For the longest time, Nakamura was known largely for his membership in Painters Eleven, though his work is far more subdued than the stylistic brashness of his colleagues. Compare Nakamura’s Summer Brilliance, 1955, for example, with Alexandra Luke’s Blue Dynasty, c.1955, or Harold Town’s Tumult for a King, 1954, and one wonders why Nakamura joined the group. Yet without Painters Eleven, Nakamura’s name might have long been forgotten. His participation opened doors for him and, ironically, because his work was so different from that of the rest of the group, it tended to stand out. He was a happy and willing participant despite his shyness, and he remained fond of his colleagues and followed news of their activities—even showing up at their art openings—long after the group had disbanded.

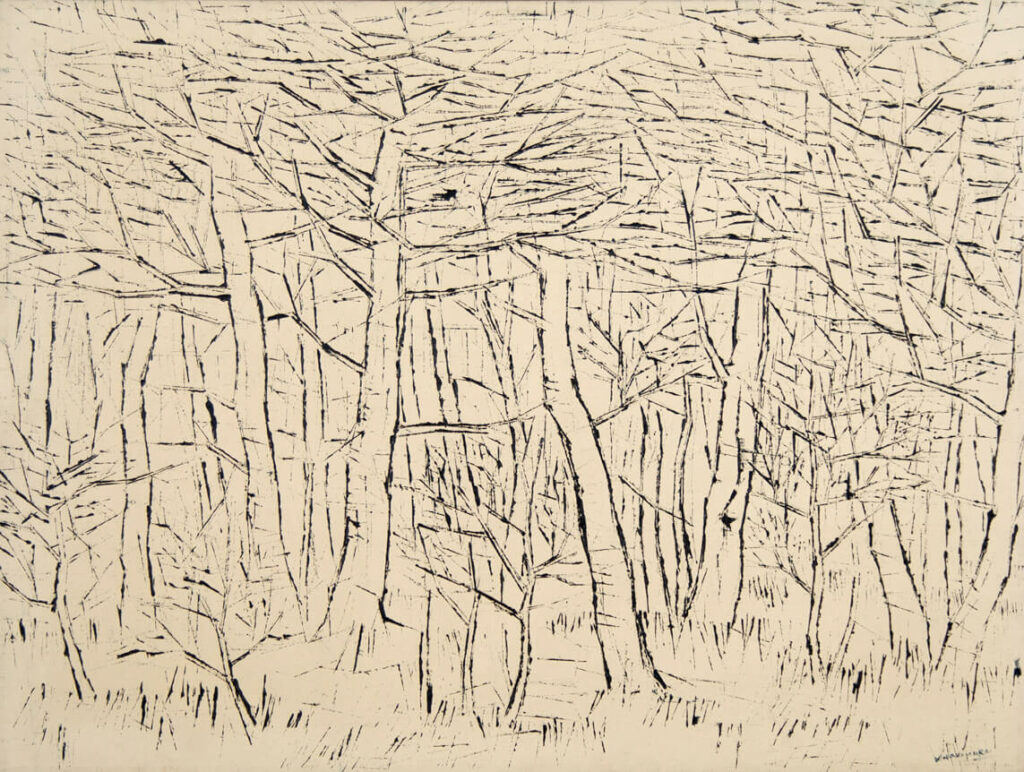

Nakamura’s involvement with Painters Eleven came as he was evolving an abstract style, as seen with Morning Landscape and Summer Brilliance; however, he continued to produce images with recognizable subject matter, as in Untitled, 1955. The other members of the group, who were all committed to abstraction, did not seem to see Nakamura’s figurative work as a concern. And only once, when Ronald was organizing Painters Eleven’s participation as guest artists of the 20th Annual Exhibition of American Abstract Artists (AAA) held at the Riverside Museum in New York in 1956, did it become an issue. The AAA instructed Ronald that all the works shown had to be abstract, a point he reiterated in a letter to Bush: “No watercolours and all abstract. No landscape to the extent of Nak’s [Nakamura’s] stuff in our last show.” Ironically, one of the two works that Nakamura submitted and exhibited was White Landscape, 1953.

The group’s early success had landed them the invitation to the Riverside Museum exhibition, and it was an important moment in all of their careers. Though the reviews for the show were underwhelming, the fact of being shown in New York alongside works by Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) and Franz Kline (1910–1962) further propelled their reputation in Canada. Unfortunately, on the heels of this international exposure, Cahén was killed in a car accident in November 1956, and Ronald resigned from the group a year later. The remaining members continued to exhibit together, with some important shows in Toronto and Montreal, for another four years. In October 1960 the group disbanded.

In the time the group was together, Painters Eleven did not have an ideology beyond wanting to expose Toronto audiences to some exciting new abstract art. The artists felt they would have far better opportunities to exhibit as a group than individually, which they had, and would gain more attention together, which they did. The group members were allowed to take their art in the direction they wanted to. As Tom Hodgson mentioned in a 1990 interview with Joan Murray, “It was their business what they did and no one ever said anything about anybody else’s work.” Nakamura, inspired by the work of his colleagues, boldly decided to try new things in his own.

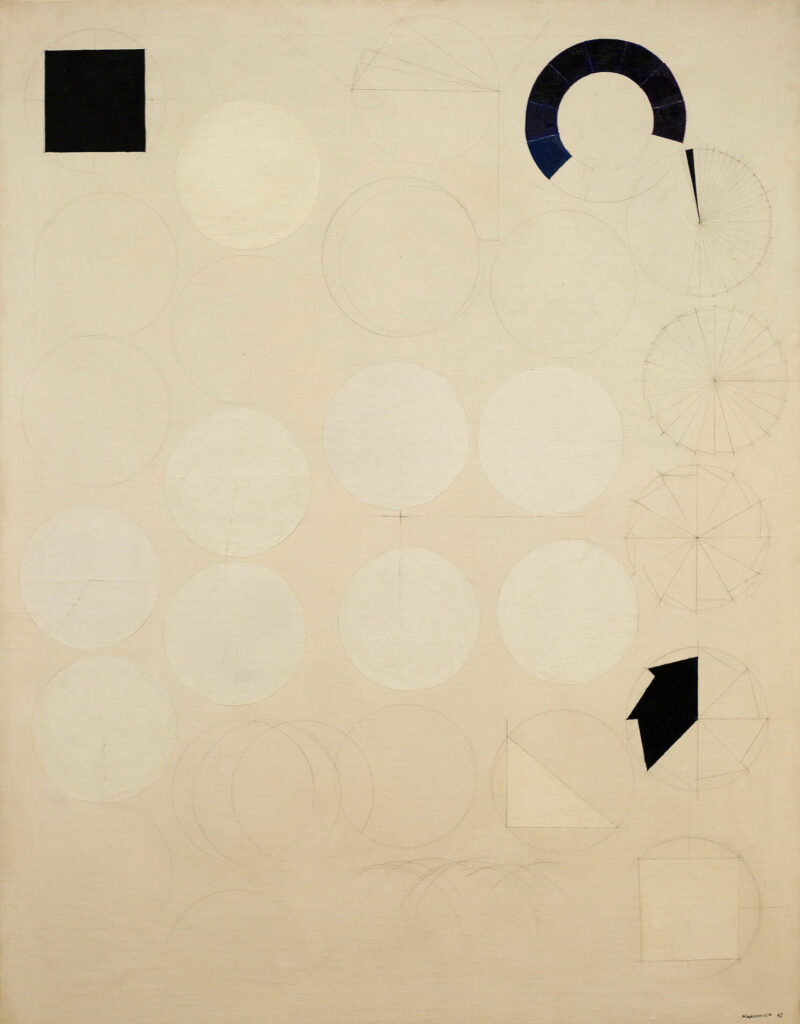

The period of Painters Eleven was a time of great experimentation for Nakamura. Although he started out predominantly painting landscapes like Farm, 1954, he then produced abstract works like Inner View, 1954, and Inner Structure, 1956. Alongside these, he painted eerie, imaginary open spaces populated by block-like forms, such as Fortress, 1956, which culminated in his 1966 public commission, Two Horizons (installed 1968). These Block paintings were widely exhibited in the mid-1950s. Then there were the String works, probably Nakamura’s most radical and innovative paintings, of which Infinite Waves, 1957, is one of the best-known examples.

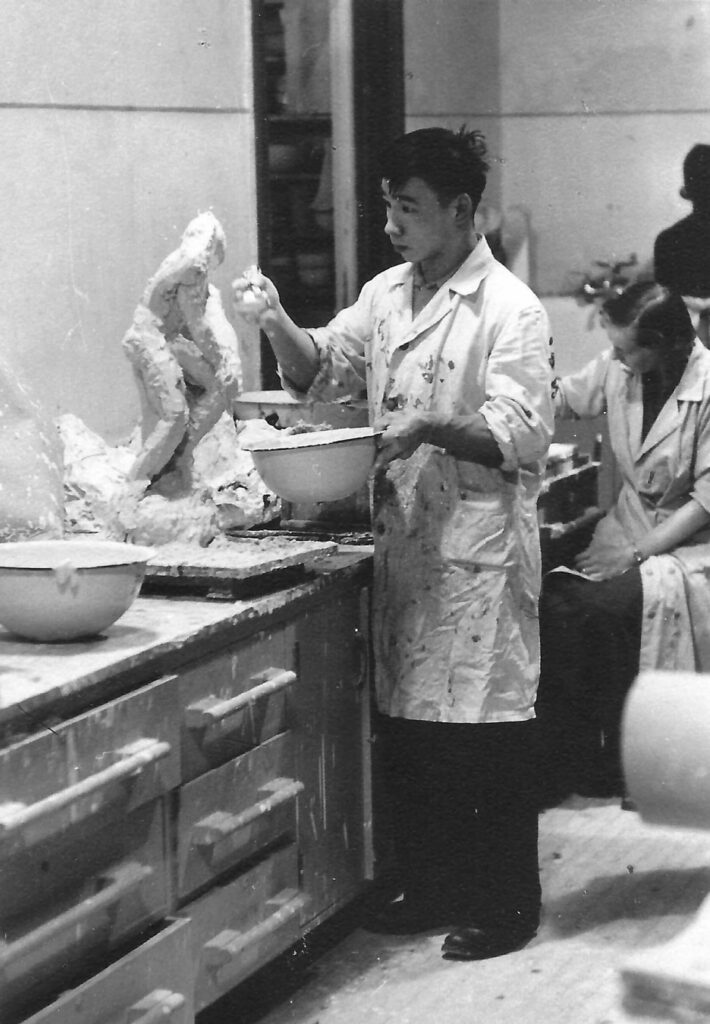

The explosion of creativity also expressed itself occasionally in sculpture. A photograph taken at Central Technical School shows that Nakamura did some sculpting as a student, and he made a bevy of small sculptures—most no taller than 50 centimetres—out of wire and Hydrocal throughout the 1950s. He only appears to have exhibited a few of them in 1958, and it is unclear what motivated him to do this and why he kept his sculpting mostly to himself. Regardless, it seems almost certain that being with members of Painters Eleven helped Nakamura work out his ideas and gave him the confidence to better articulate them. His interest in science, for example, began to manifest itself more overtly during this period.

Nakamura’s involvement with Painters Eleven also likely helped him achieve successes outside the group. In 1955 his work was selected for the First Biennial Exhibition of Canadian Painting at the National Gallery of Canada. In early 1956 Nakamura received a prize from the International Exhibition of Drawings and Engravings in Lugano, Switzerland, for an ink drawing titled Four Bridges, 1954. The work was inspired by the view on a train trip he made to visit some old friends and colleagues at Kraft Containers in Hamilton. That same year the Smithsonian Institution featured his work in the Canadian Abstract Painting exhibition, which was organized by the National Gallery. And between 1957 and 1959 he showed his work in twelve international exhibitions. This individual success may have had Nakamura questioning the value of remaining with Painters Eleven.

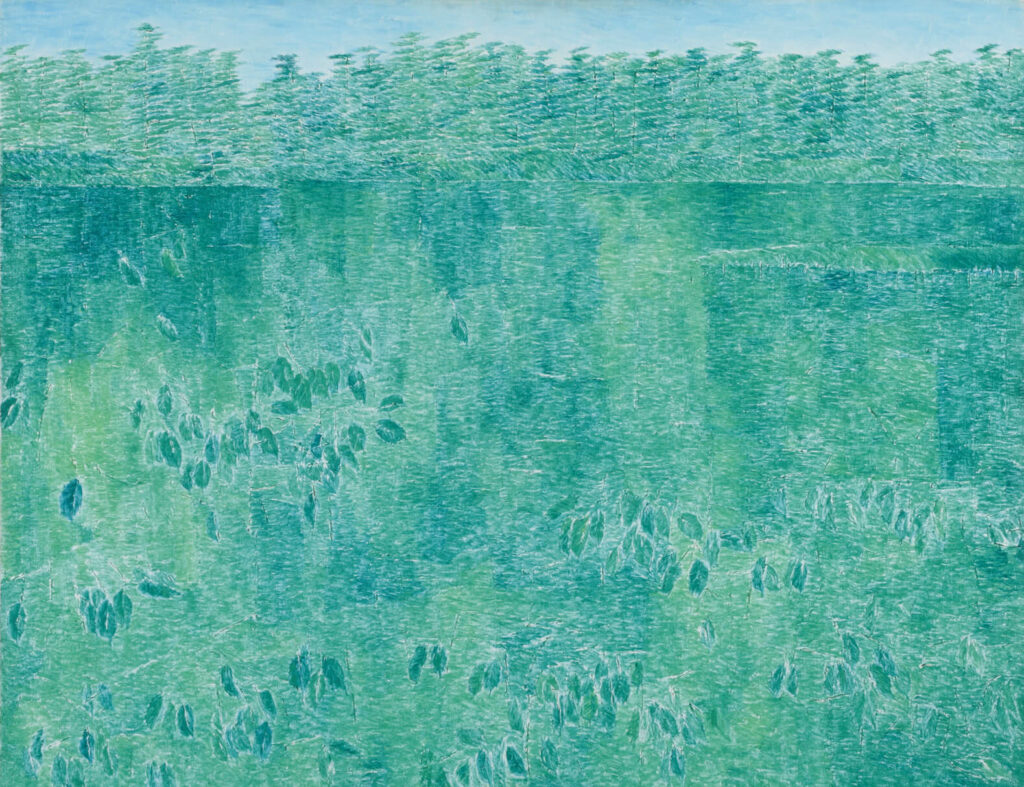

Reflections on Art and Life

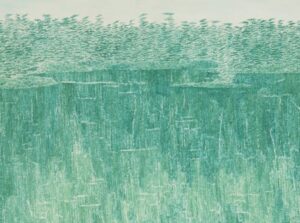

By 1960 Kazuo Nakamura was at the height of his artistic career, both widely exhibited and collected. The beginning of the decade saw the emergence of his most popular works, his blue/green landscapes. Lakeside, Summer Morning, 1961, is an excellent example. These became so popular that even when he started to make his Number Structure paintings in the 1970s, he continued to produce the occasional landscape in this style because they sold quickly. And when art dealer Jerrold Morris added him to his stable of artists in 1962, Nakamura acquired a measure of financial security.

Nakamura’s international success continued throughout the decade. In 1961 Alfred Barr acquired Inner Core 2, 1960–61, for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), and purchased a couple of Nakamura’s other works for private American collectors. Barr, who collected the Russian artist Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) for MoMA, likely saw Nakamura’s work as a continuation of the abstract tradition that Malevich helped originate. MoMA’s director was probably also aware of Nakamura’s String paintings, which he may have considered part of a broader resurgence of monochromatic abstraction represented by the work of Agnes Martin (1912–2004), Robert Ryman (1930–2019), and Piero Manzoni (1933–1963), to name a few.

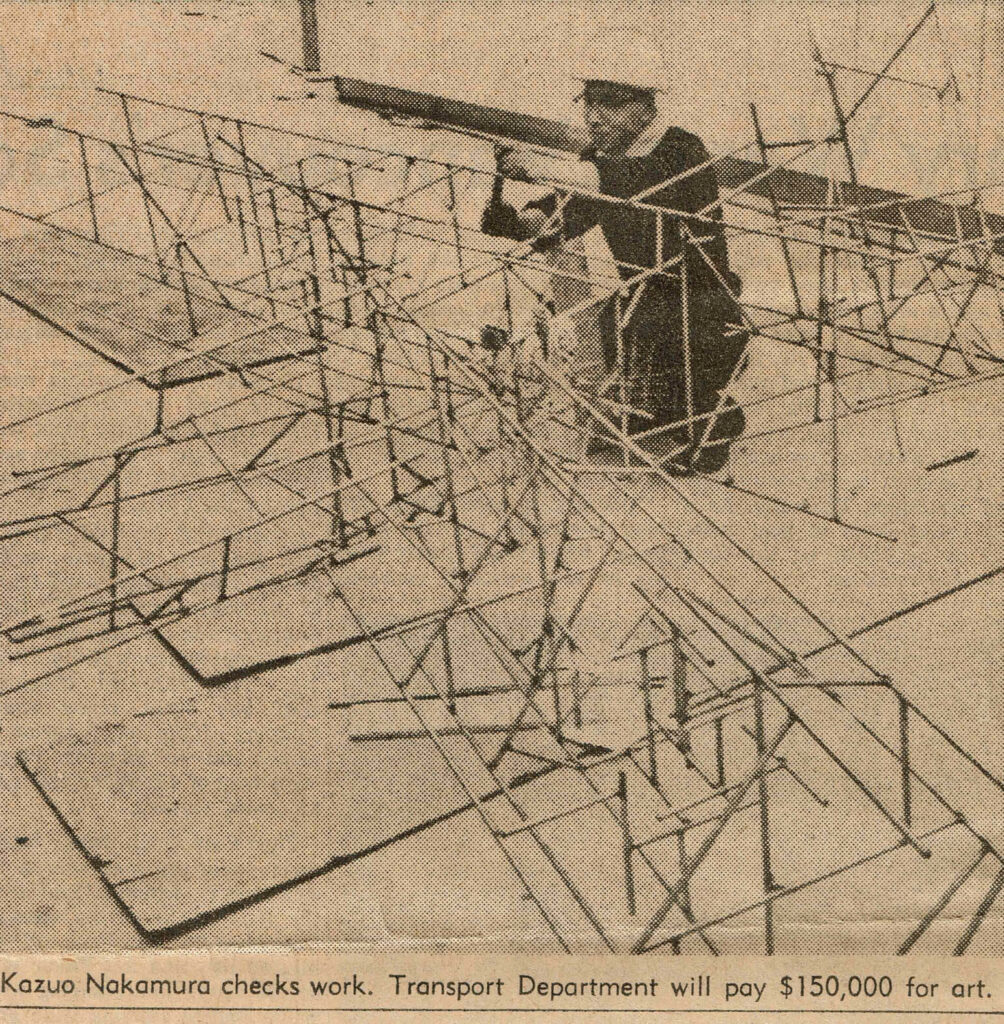

In the mid-1960s Nakamura participated in two public commissions: a sculpture for Toronto International Airport (now Toronto Pearson International Airport) that was installed in early 1964, and a painting for the Ontario legislature at Queen’s Park in 1968. Both pieces were uncharacteristically large. Galaxies, Nakamura’s nod to early aviation, was notable for two reasons. First, the sculpture recalls the Wright brothers’ plane and flagged Nakamura’s deeper commitment to science and geometric forms. Second, the installation caused an uproar because of the amount of taxpayer money being spent to acquire and build it. A headline in Toronto’s Globe and Mail read, “Airport Art Will Cost $150,000,” and the Toronto Daily Star proclaimed, “Now YOU Are Canada’s Biggest Art Patron.” Neither article complained about the work that was being commissioned. A committee that included the directors of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario), and the National Gallery of Canada had made the final selections, and the quality of all the works made for the airport was remarkable. Two Horizons, 1968, the painting for Queen’s Park, was installed without controversy.

Throughout the 1960s Nakamura also devoted time as a volunteer for the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre, both as an adviser before the building was completed in 1963 and in a variety of roles afterward. It is difficult to say why suddenly Nakamura immersed himself in the Japanese community in Toronto. His brother Mikio, who served as the centre’s president for a time, may have encouraged him. Or the community may have reached out to him as a result of his artistic success. Perhaps he felt he owed something to other Japanese Canadians. By that time he certainly was one of their cultural stars—at least until an interview in Tora in 1972 in which he stated that through intermarriage “Japanese blood—and the Japanese tradition—will disappear.”

Nakamura himself married in 1967, at the age of forty. He and his wife, Lillian Yuriko Kobayakawa, would have two children, a daughter born in 1968 and a son in 1975. By all accounts, Lillian became the bedrock of Nakamura’s life. She afforded him further peace of mind, which permitted him to focus on his growing passion for geometry and mathematics.

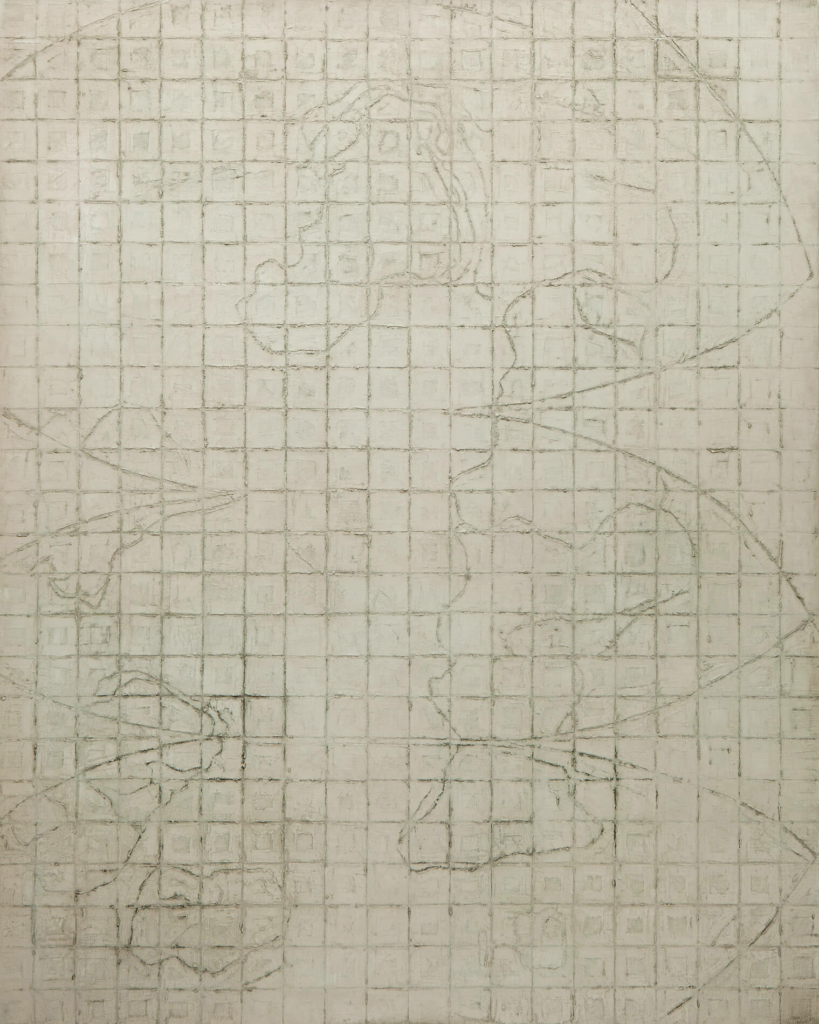

By the late 1960s and the 1970s, Nakamura’s career was firmly established. The geometric forms and grids, as in Geometric Suspension, 1969, were a natural progression in the evolution of his art, a point he illustrated explicitly in Spatial Concept/Evolution, 1970. Then he was honoured with two retrospective exhibitions. The first was held at the University of Toronto’s Hart House in 1970. The second important retrospective of his work took place just four years later at The Robert McLaughlin Gallery. In the catalogue for that show, Nakamura published his first and only major statement on his work, outside of interviews. He writes:

To analyze art is as complex as science analyzing universal structure and evolution which are based on certain logic and order.

Art is not just emotional vision but more of man’s concept or equation of his environment and thoughts.

In the history of art, all civilization and its developing period must be relative to the universal scientific and philosophic concept of its time (or the scientific and philosophic concept may be relative to art).

Every developing phase and facet of science must produce some form of art.

Here Nakamura outlines the modus operandi for his work to come. He had been preparing the ground for it in the preceding years, but he undertook the journey in earnest after 1974.

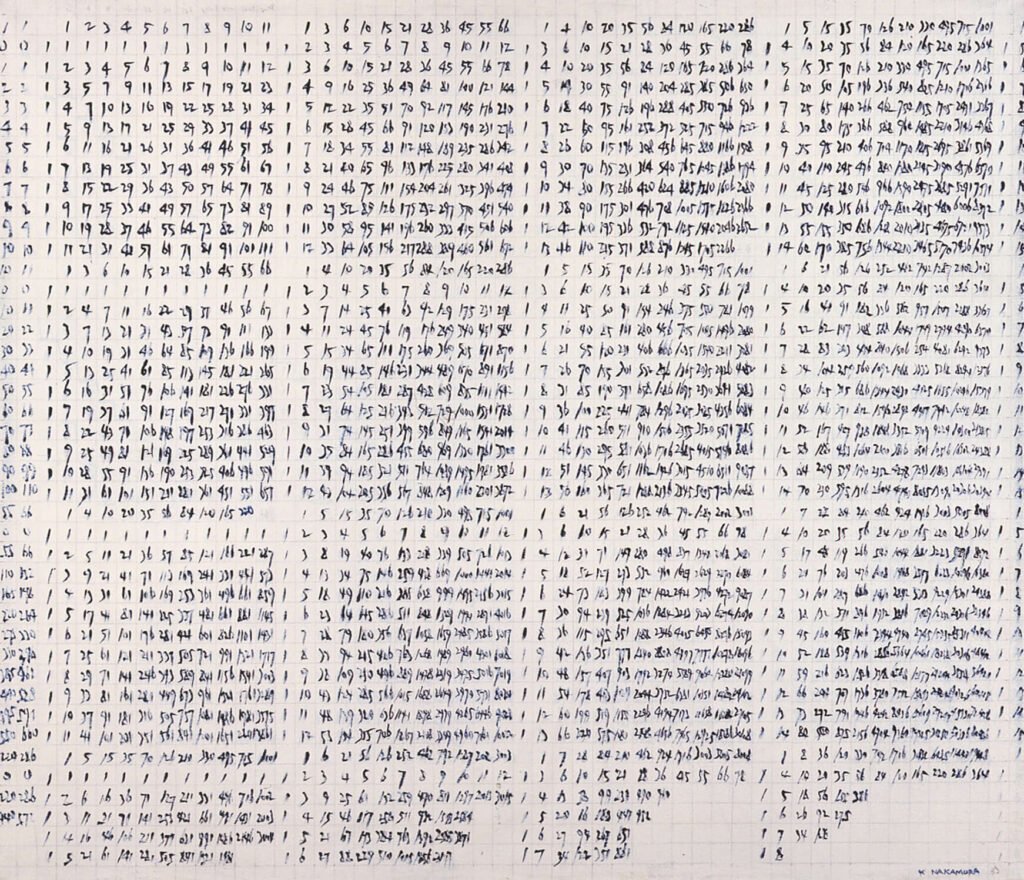

Paint by Numbers or Numbers to Paint By

The Number Structure works were, in Kazuo Nakamura’s mind, his most important body of work, the culmination of his career. They involve the meticulous calculating and writing out on paper and canvas of numerical sequences in a variety of grid patterns. It was the ability of numbers and sequences to describe universal patterns in nature—such as the rate of growth of the rabbit population, the arrangement of scales on a pine cone or petals on a field daisy—that drew Nakamura to them, and in the Number Structure works he would paint/write out a variety of these, including Fibonacci numbers, Pascal’s triangle, Catalan numbers, and fractals. Unfortunately, these works disappointed many collectors who associated Nakamura with the paintings he had produced with Painters Eleven. Yet he held that the patterns and themes he was exploring in the Number Structure series lay at the core of all his earlier work.

For a decade after the McLaughlin retrospective, Nakamura stepped back from the art world to focus on the number paintings. He exhibited those works in a major show at the Moore Gallery in Hamilton in 1984. And then, as art dealer Christopher Cutts acknowledged, Nakamura almost entirely stopped contributing new works to exhibitions. He was criticized for becoming something of a hermit, to which he responded: “I’m not really a recluse, I just don’t have any small talk.”

By the mid-1980s Nakamura finally began to translate some of the numerical series or patterns he had been recording on reams of squared paper. As he stated in a 1993 interview, “I was always interested in internal structures, the law of order that lies in everything…. But I’m doing my most important work now.” On occasion he produced a representational painting, usually a landscape—Reflections, 1983, and Untitled, 1986, are examples. These always sold well. They were also reminders of the visual manifestations the numerical patterns generated. As he put it: “It takes energy to do abstract work. Every once in a while I do landscapes, to do what’s on top.”

In 1986 Nakamura returned to Tashme for the first time since the war. He and Lillian visited Vancouver and Expo 86, then drove with Lillian’s brother to Hope to visit the “old camp,” as Lillian called it in a letter to artist Brian Grison. There is no record of Nakamura’s response to this visit, though he drew a sketch of the camp around this time, either during the visit or sometime before the fiftieth anniversary reunion held in Toronto in 1992.

With Nakamura attending fewer events and his art dealer, Jerrold Morris, unenthusiastic about the Number Structure works, the artist might have slipped from view. However, in 1987 Nakamura met Christopher Cutts, who showed a keen interest in the number series. Cutts spent a great deal of time visiting Nakamura, who clearly appreciated the interest and explained the number series to him. The result was one of the better and more accessible texts mapping out the various sequences and their rationale in Nakamura’s work. Cutts became Nakamura’s new dealer and ensured he would remain in the public eye.

In the following years, Nakamura continued his work on numbers while cheering on his favourite baseball team, the Toronto Blue Jays. He sold two drawings—Vertical Lines, 1953, and Evening No. 2, 1964—to the British Museum in 1993, and was named an honorary fellow of the Ontario College of Art and Design (now OCAD University). However, sometime in the late 1990s Nakamura began to develop symptoms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig’s disease, and eventually was no longer able to draw. His health quickly deteriorated at the time his work was coming back into prominence nationally, and he died on April 9, 2002, at the age of seventy-five.

Nakamura lived long enough, though, to see two more important exhibitions of his work. In 2001 the Gendai Gallery of the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre held an exhibition of the Tashme works, which had rarely been shown. That same year, The Robert McLaughlin Gallery put together a major retrospective that toured the country, framed by stops in Prince Edward Island and Saskatchewan. Nakamura was also aware that the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in Toronto was planning a major exhibition of his works. And in 2004, the AGO honoured him with the retrospective exhibition Kazuo Nakamura: A Human Measure. These three shows were a fitting tribute to the life of one of the great lights of modern art in Canada.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements