Seeking inspiration beyond the conservative art scene in Toronto, Kathleen Munn absorbed the lessons of the international modern art movement in New York and Europe to create her signature paintings in the 1920s. In the 1930s she devised her own unique drawing technique to achieve a new visual vocabulary.

New York Modernism

Munn absorbed the lessons of the Ashcan School artists George Bellows (1882–1925) and Robert Henri (1865–1929) when she attended the Art Students League (ASL) in New York in 1912. Her art was profoundly influenced by her studies in New York and by her visits to the Metropolitan Museum of Art between 1912 and 1928.

Munn’s early paintings are characterized by broad brush strokes and dark tones capturing the personality and expression of the subject. The Globe critic praised her “boldness of execution” and unique imagination in the paintings she exhibited upon her return to Toronto. Munn’s “study of a woman’s head is strikingly individual…. The artist conveys the impression of an unusual personality,” wrote a reviewer in the Star in April 1913.

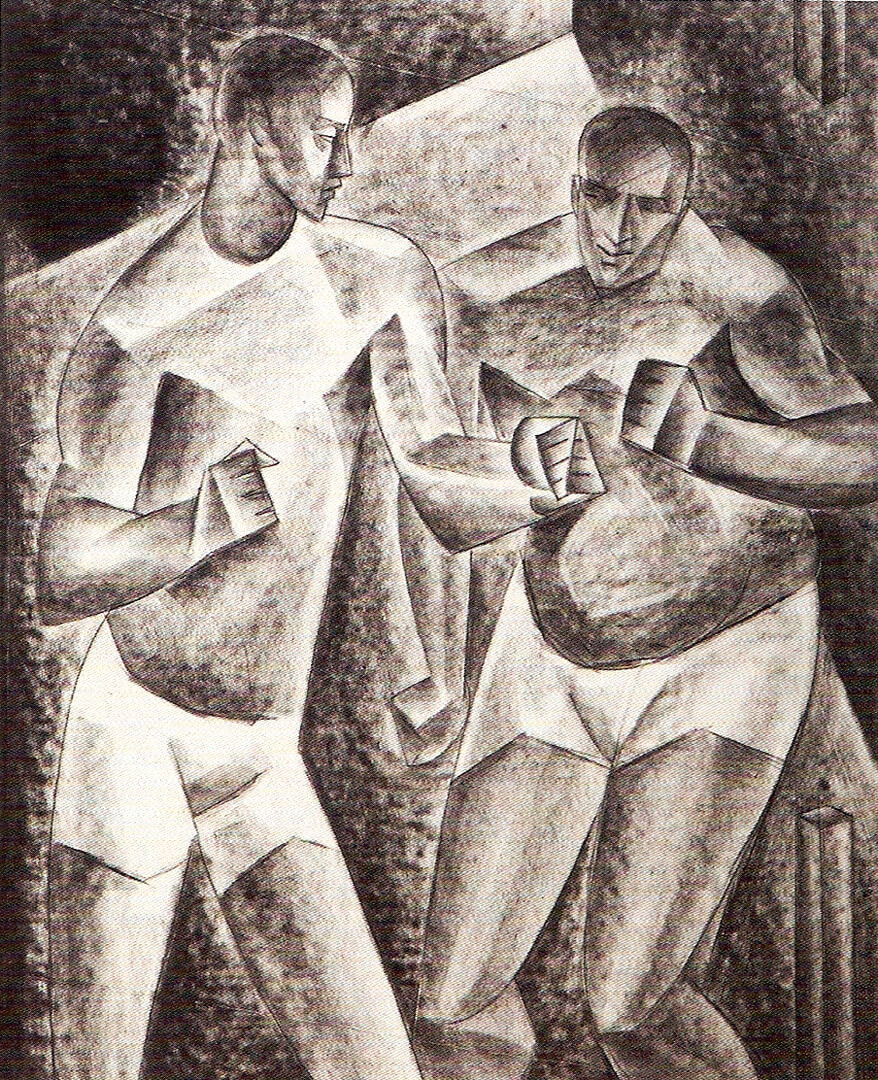

Munn’s style changed dramatically in the 1920s, though she continued to be inspired by George Bellows. Around 1925, the year of his memorial exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum, she drew and painted a pair of boxers. These works reference Bellows’s Both Members of This Club, 1909, which was centrally installed in the retrospective.

American Cubism

In the early 1910s Munn studied at the ASL summer school in Woodstock, New York, with American artists Andrew Dasburg (1887–1979) and Max Weber (1881–1961), both greatly influenced by Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) and Cubism. She was awarded a first prize in Woodstock in 1914.

Munn read widely and attended lectures on a variety of topics: the history of art and design, art theory, literature, philosophy, mythology, and music, among others. She recorded her studies from this time in her Notebook 1, for future reference. Among the texts she read were Modern Painting: Its Tendency and Meaning by Willard Huntington Wright, and “The Ancestry of Cubism” by Jay Hambidge (1867–1924) and Gove Hambidge.

Synchromism

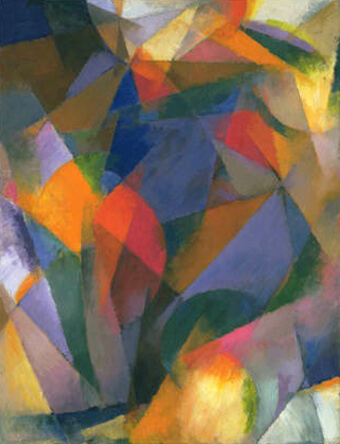

During the 1910s and 1920s Munn’s work was dominated by the Synchromists’ use of colour to define form. She studied The Creative Will: Studies in the Philosophy and Syntax of Aesthetics by Stanton Macdonald-Wright (1890–1973), published in 1916, and knew his work and that of fellow American and French Synchromists: Morgan Russell (1886–1953), Robert Delaunay (1885–1941) and Sonia Delaunay (1885–1979), and Andrew Dasburg, her teacher.

These artists spoke of colour rhythms, masses, contrasts, directions, and continuity. Colour, above all, was central to her painting. Munn wrote in her notebook that “painting is little more than a transcription of sense impression and of accent of vision, light, dark, red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet; up, down, right, left, straight, round, large, small and so on.”

The Synchromists also asserted the primary importance of the human body. Brothers Willard Huntington Wright and Stanton Macdonald-Wright had a devoted interest in sculpture and the rhythms of the human form—they were highly influenced by the sculptures Slaves by Michelangelo (1475–1564), begun in 1513. These works also link to Munn’s figures in the Passion series, which feature contorted human figures.

Abstraction

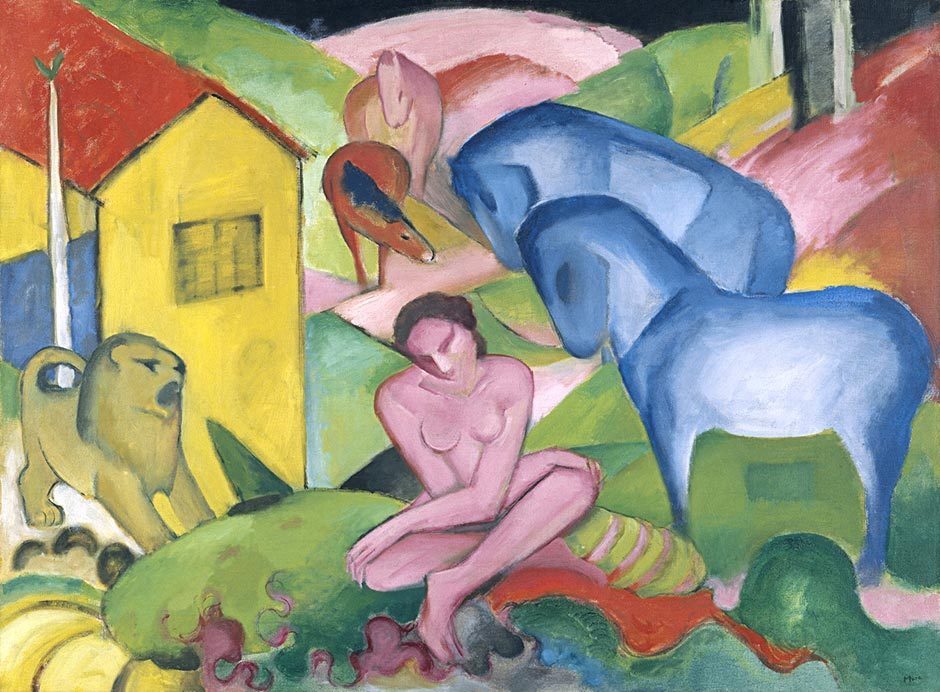

In 1927 a landmark event took place in Toronto: the International Exhibition of Modern Art was brought to the Art Gallery of Toronto (now Art Gallery of Ontario). Arranged by the Société Anonyme (an art organization co-founded by Katherine Dreier), this large exhibition included major works by Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), Franz Marc (1880–1916), and Constantin Brancusi (1876–1957), among many others, and was the Canadian public’s introduction to international modernism and abstraction. Tours and lectures were organized to promote the importance of modern art, and Kathleen Munn is believed to have given a talk at the exhibition.

It was at this time that Munn began to experiment with pure abstraction, though it was a brief foray. Untitled I and Untitled II, both c. 1926–28, are abstracted land forms expressed in bold colours; rhythm and movement through space are the artist’s key concerns. As with the works of Bertram Brooker (1888–1955) and Lawren Harris (1885–1970), Munn’s abstract painting was in part inspired by the theosophical writings of Helena Blavatsky and the notion of the fourth dimension developed by P.D. Ouspensky. Munn’s Notebook 4 records her reading of these and related texts.

It is unlikely that Munn ever exhibited her abstract works—after her death the canvases were found rolled up and stored. However, these abstracted forms feature prominently in Munn’s mature paintings from the mid- to late 1920s, such as Composition (Reclining Nude); Untitled (Deposition); and Untitled (Ascension), in the York University Collection, Toronto; and in many of her drawings of figures in landscape.

The Figure in Landscape

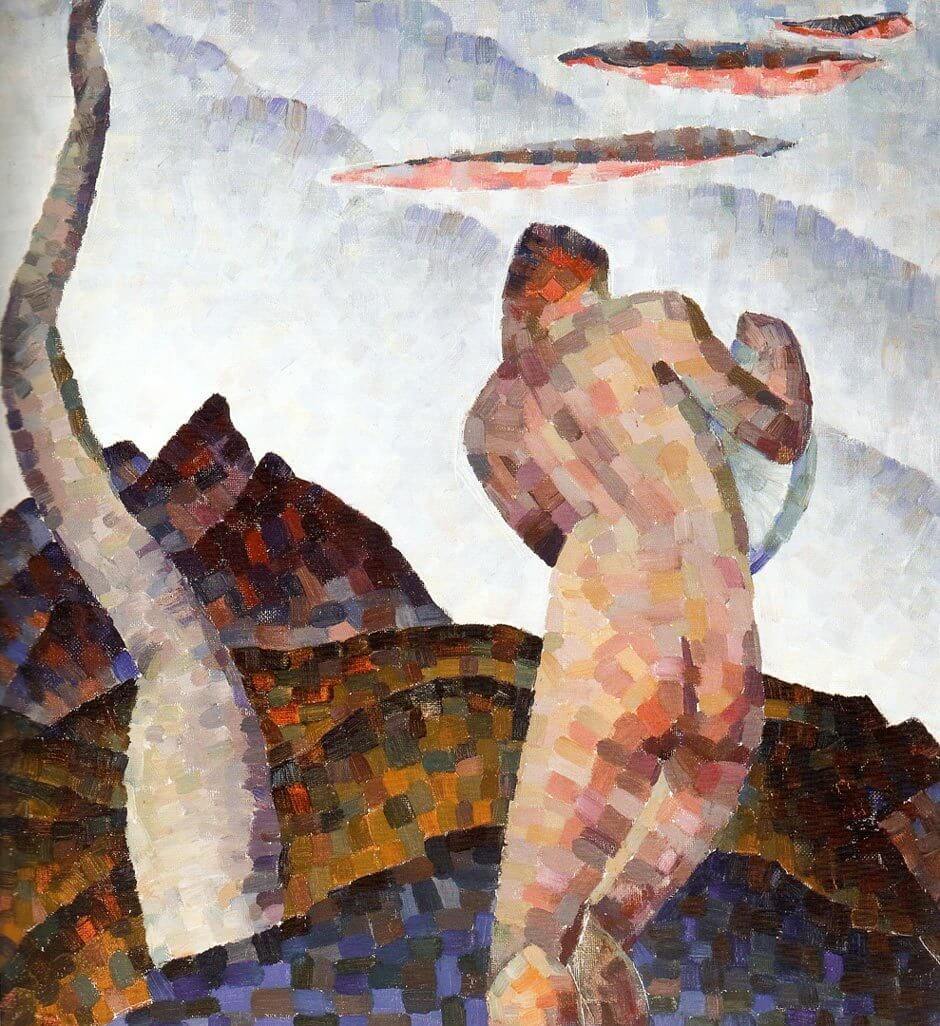

Throughout her career Kathleen Munn was first and foremost a dedicated student of the human figure. The 1920s was a decade of great experimentation and learning for Munn, one that led to an eloquent flourishing in a number of related pictorial styles and to her reimagining the conceptual potential of the human figure.

As the art historian Anna Hudson asserts, “Munn saw the body as a complex aesthetic instrument, richest in its discordant tension of representational and abstract readings. As such, she recognized the transgressive power of the nude as a subject of modern art.” Although she drew the human form from live studio models, Munn also studied the figure as an idealized form—as created by ancient Greek sculptors, reimagined by the Renaissance masters, and reinterpreted by Alexander Archipenko (1887–1964) and Brancusi, by way of El Greco (c. 1541–1614), George Bellows, and Henri Matisse (1869–1954).

Munn’s take on the classical subject of “the bathers” is entirely her own. With it she explores the way a single figure resonates with the natural features, as in Untitled (Figure in a Landscape), c. 1928–30, where the form of a standing nude echoes the curves of a solitary tree. Most often Munn is interested in a group of figures interacting in space, as in Untitled (Four Figures in the Woods), c. 1928–30. These paintings are about composition and rhythm. Munn also incorporated geometric principles here, and she refined her use of colour.

A Method of Her Own

Until the early 1930s Munn’s drawings were studies and sketches for her paintings. With the Passion series, however, her methodology changed, and drawing became her primary practice. Black ink and graphite now superseded the centrality of colour for Munn. First exhibited in 1935 and now known as the Passion series, these works are the culmination of a long, meticulous process of experimentation.

Munn’s papers include diagrams in which she developed Jay Hambidge’s concept of the “whirling square” into a cube using a compass. She translated the whirling square into an expression of three-dimensionality so that she could apply it to her theory of how to draw the human form in motion. Munn was also aware of the photographic studies of Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904), of animals and humans in motion; she made numerous sketches recording how a body twists and noting proportional differences between male and female bodies. Her drawings included annotations, such as “first lay out pose of head on neck and planted firmly on its feet” and “use pit of neck as pivot.”

Ultimately Munn devised a unique technique to build a figure and express its countless positions and views in space. She created a template for each key position, each having origins in the whirling square but now reconfigured into a system used to generate movements in a human figure. Bodies twist, are foreshortened, reach upward, fall, bend, or kneel. Munn reduced the contorted and moving figures to schematics, even using a numbered system to identify unique templates that refer to specific poses and actions.

Munn’s Light Box

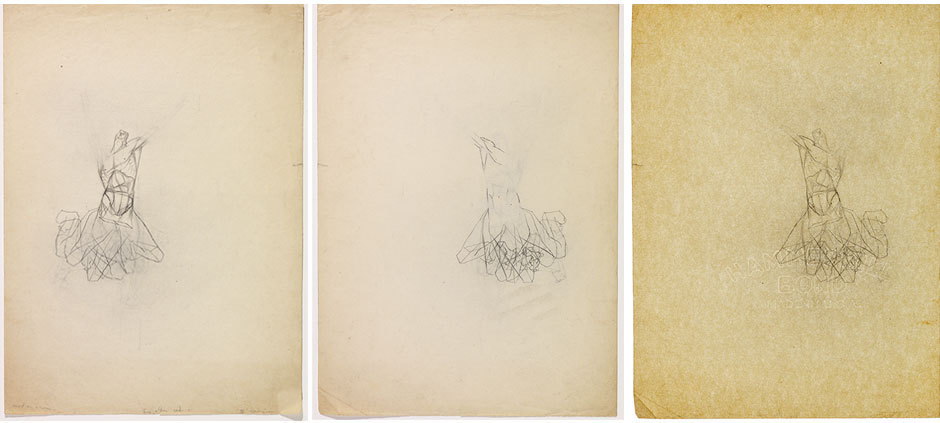

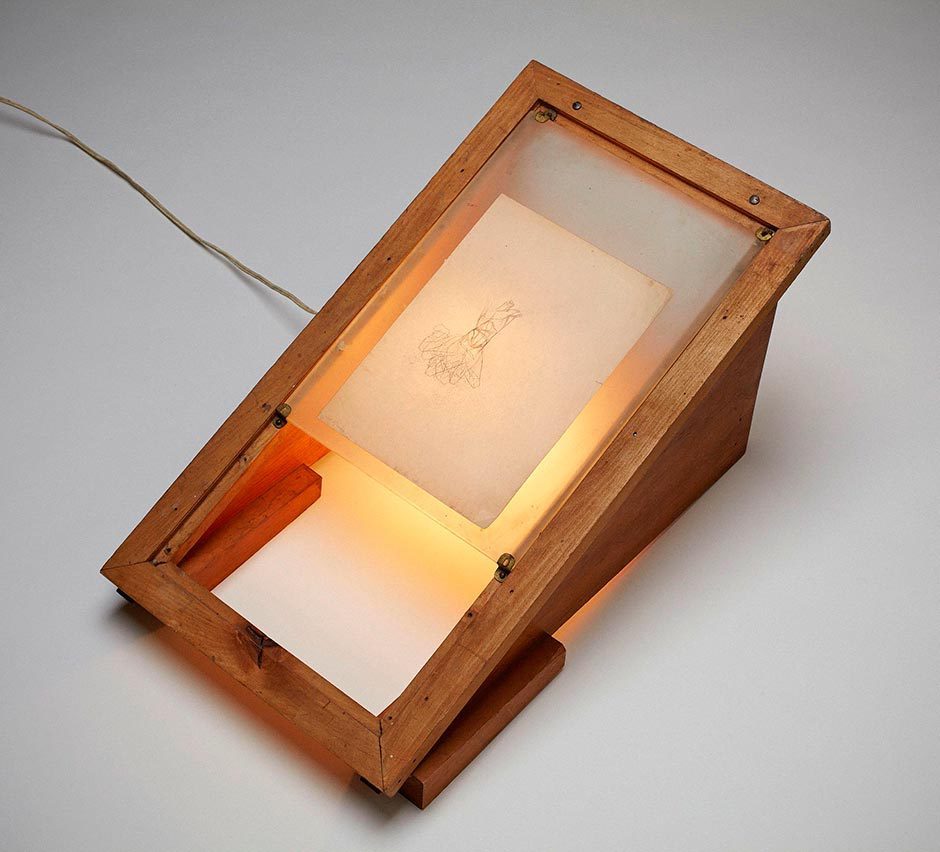

In the late 1920s or early 1930s Munn’s nephew William Richards constructed a light box to her specifications. It was rediscovered in 2010 and led to a deeper understanding of Munn’s innovative drawing process and technique for the over one thousand preparatory drawings for the Passion series.

The light box was fundamental to her method of building a figure and expressing its countless positions and views in space. Using small- or medium-sized sheets of thin typewriter paper, Munn transferred a specific schematic template from sheet to sheet and then drew multiple legs or arms in various positions on both sides of the paper. This process enabled almost endless permutations of the figure in motion.

Munn would then make notes on the sheet: “head falling down,” “get arm on left,” or “try this for erecting figure on cross.” She also indicated figures for use in depicting certain episodes of the Passion—such as Deposition, Mount of Olives, and Ascension, among others. Munn sketched the interaction of multiple figures in hundreds of drawings, producing sets of crowds, which she then collaged. The single-figure drawings have numbers in the corner, referencing a system (possibly of her own invention) yet to be decoded. Rarely dated and never signed, some of these study drawings are found in private collections in Canada.

Munn’s meticulous experimentation led to the creation of the large finished drawings, including Crucifixion (Passion Series), c. 1934–35, Untitled (Descent from the Cross), c. 1927, and Last Supper, 1938. The reviewer G. Campbell McInnes lauded this series in 1935 for its “cumulative effect on one as almost awesome.” Munn’s close friend and fellow artist Bertram Brooker called the works “simply stupendous.” These drawings reveal the intensity and resoluteness of her project as well as her relentless perseverance and single-mindedness. They also give us an intimate understanding of her working method—a deep and irresistible passion.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements