Kathleen Munn (1887–1974) is recognized today as a pioneer of modern art in Canada, though she remained on the periphery of the Canadian art scene during her lifetime. She imagined conventional subjects in a radically new visual vocabulary as she combined the traditions of European art with modern art studies in New York. She died at age eighty-seven, unaware that her long-held hope for “a possible future for my work” was about to become reality.

Family Life

Kathleen Jean Munn was born into a large, closely knit middle-class family in Toronto in 1887. The Munns’ background was Methodist, but religion did not play a role in family life. James and Catherine (née Wetherald) Munn owned and ran a jewellery store at the intersection of Yonge and Bloor, and the family lived in the apartment above. They had three boys and three girls: Clarkson (died as an infant), William (ran the Munn store), Fredrick James (a doctor who died young), May (a teacher), Elizabeth Agnes (known as Marjorie, a teacher, moved to Manitoba), and Kathleen. Munn’s parents valued education above all and supported the children’s efforts to pursue their interests.

William, May, and Kathleen lived together as adults, moving from Yonge Street to a home on Spadina Road (south of St. Clair Avenue) in 1912 or 1913. A few years later Kathleen Munn had separate living quarters built onto the house, along with a studio with large windows facing west into the ravine.

Munn’s singular commitment to art was fostered and protected first by her mother and then by her sister May. Catherine Munn paid for her daughter’s art education, sending money and letters of encouragement while she studied in Philadelphia and New York in the 1910s. In the 1920s and 1930s, May Munn took care of all household duties so that her sister could focus on her art.

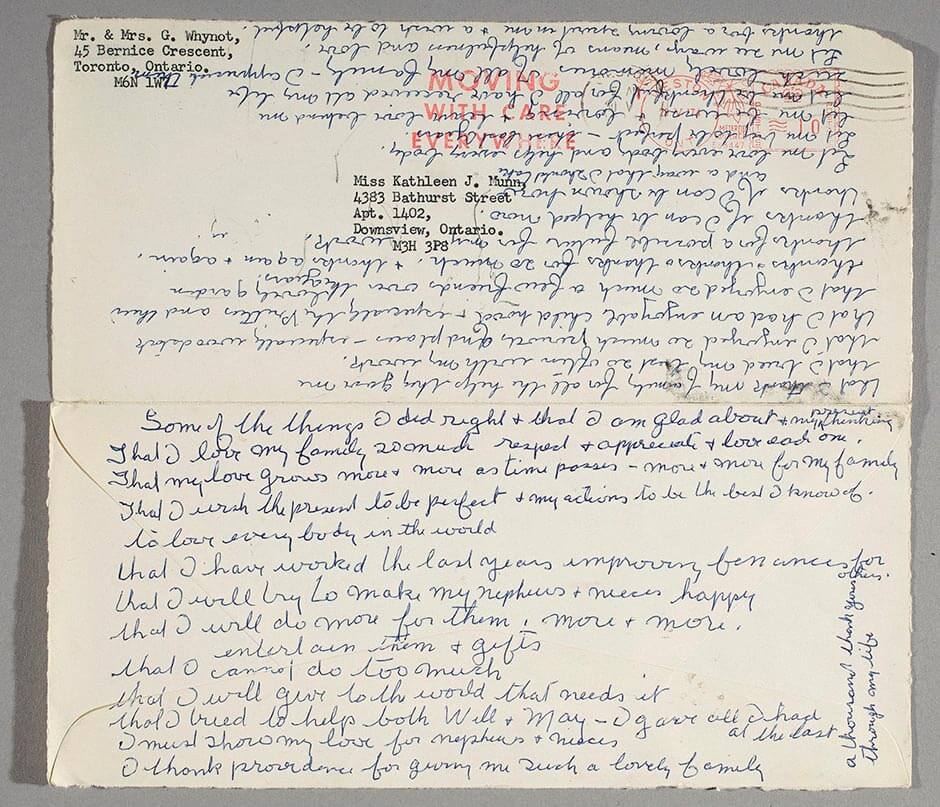

Around 1939, after her brother William died of diabetes and her sister May became physically disabled, Munn had to oversee the closing of the jewellery store business. She did not return to making art after this period. Following May’s death in 1967, Munn lived in an apartment on Bathurst Street (near Sheppard Avenue) until her death in 1974.

Details of Munn’s personal life are limited. There are no known private letters or journals, and those who knew her best have since passed away. She had a close circle of friends in the arts community, including Bertram Brooker (1888–1955), but never married and had no children. Munn’s nephews and nieces remember her as devoted primarily to her art—a preoccupation she did not easily share and one not understood by most of them. They supported her nonetheless, and in return Munn was deeply attached to them. Her niece Kathleen (Kay) Richards took over the estate to safeguard Munn’s artistic output.

Early Art Life

I believe in myself, since it is all I have.

—Kathleen Munn, c. 1925

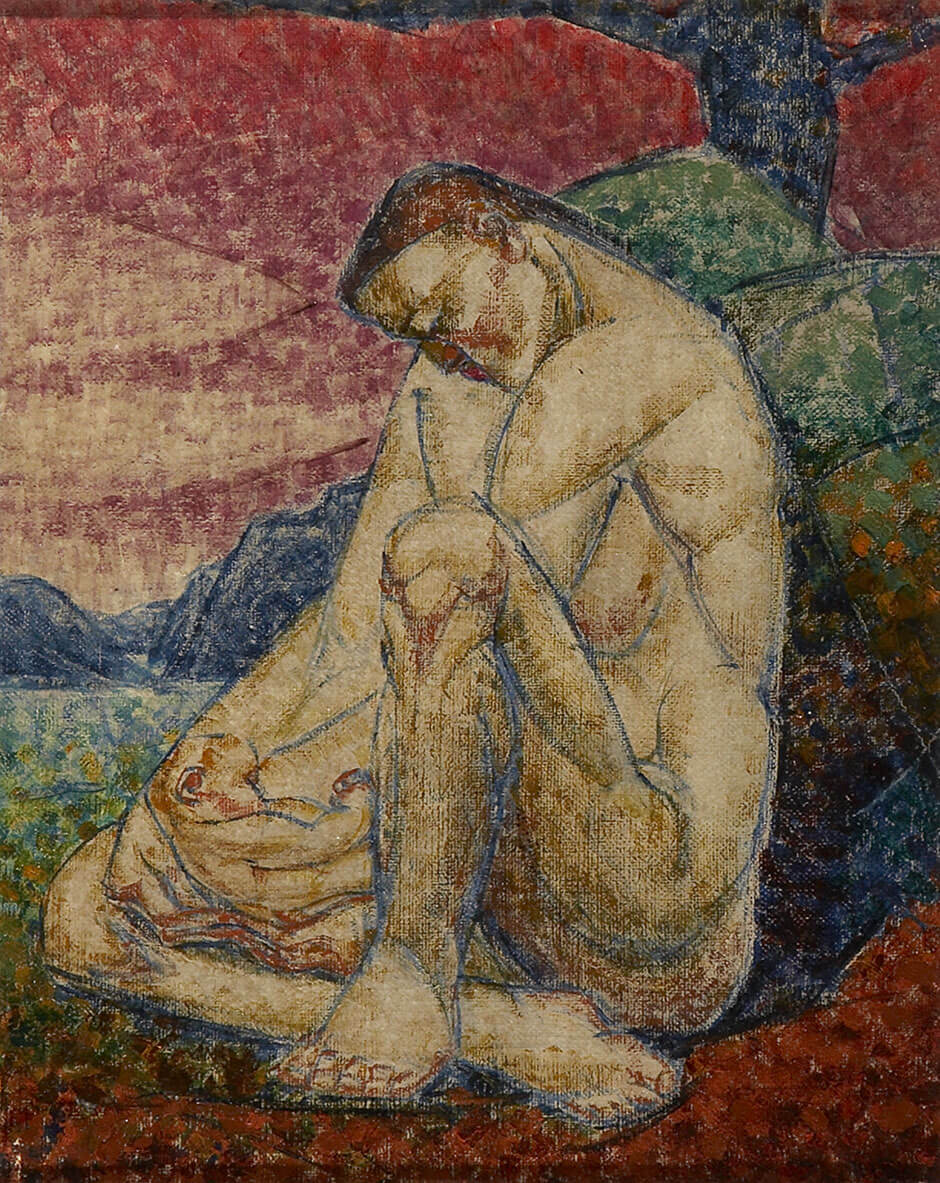

Munn’s art spans three decades in the early twentieth century and plays an important role in the development of modern art in Canada. Her subject matter was established early and did not change: landscapes, figure studies, biblical themes, and still lifes.

Although Munn did not date or title her works unless they were included in an exhibition, her output can be divided into two categories. The first, from the period 1909–29, includes paintings that reflect her exploration of artistic movements such as Post-Impressionism and Cubism; the second, 1929–39, highlights her rigorous experimentation with dynamic symmetry, culminating in her most innovative series of drawings, the Passion series.

Munn’s formal art training began when she attended Westbourne School in Toronto from 1904 to 1907 and studied with Farquhar McGillivray Knowles (1859–1932), a successful local landscape painter. Encouraged and talented, Munn began to show her work in 1909 in exhibitions with the Ontario Society of Artists and the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and at the Canadian National Exhibition, receiving some attention in reviews. She continued to exhibit with these societies until the late 1920s.

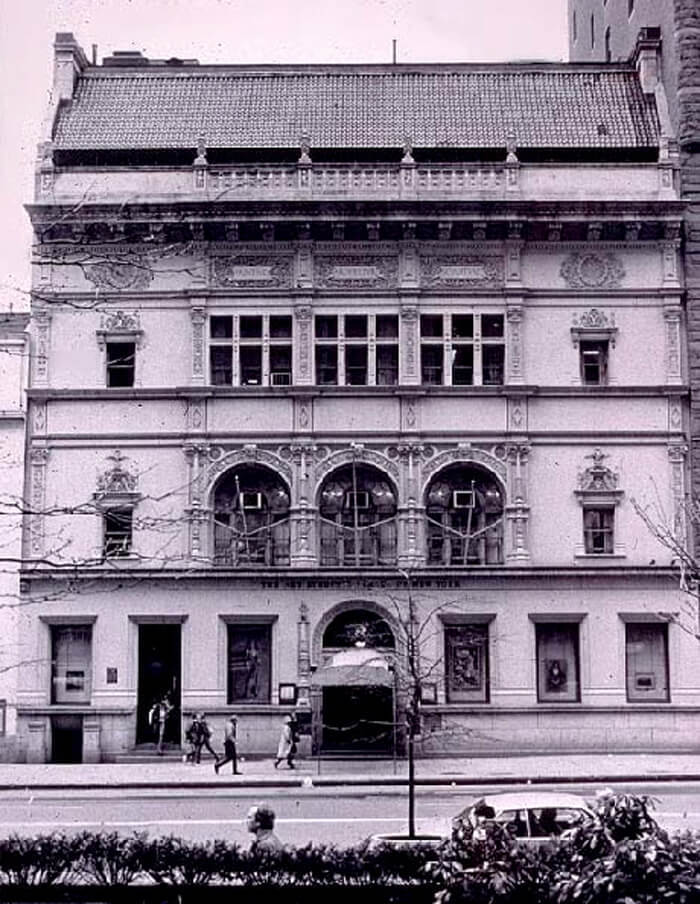

In 1912 Munn began studies at the Art Students League (ASL) in New York—the renowned modern art school established in 1875 by artists for artists. There, through her teachers, she placed herself in the heart of the American avant-garde art movement and experimented with techniques and styles, such as Post-Impressionism, Cubism, and Synchromism—a decision that distinguished her from most of her Canadian contemporaries.

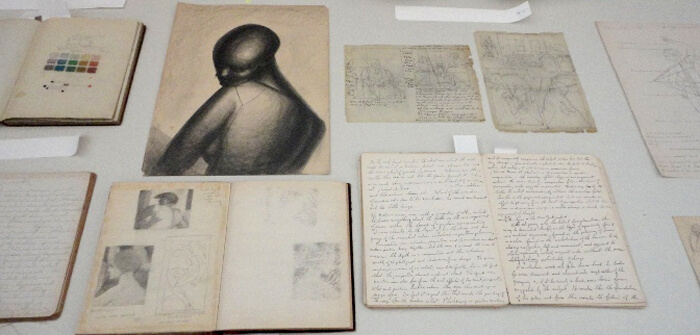

Munn recorded her studies in Manhattan, as well as those at the ASL summer school in Woodstock, New York, in nine notebooks. She continued her studies at the ASL until the late 1920s. Munn considered her time in Woodstock as the most enjoyable of her life, and sometime in the 1920s she purchased property there hoping to build a studio. Unable to realize her plans, she sold it in the early 1940s.

In New York Munn was introduced to the writings of Jay Hambidge (1867–1924), an artist and writer who developed the influential theory of dynamic symmetry. She likely attended his lectures as early as 1919. Hambidge’s essays confirmed for Munn the primacy of the human form and suggested to her the basis of a methodology for its representation.

Munn probably met Canadian artist and writer Bertram Brooker sometime in the mid-1920s. Inviting her to weekly gatherings in his home, he became Munn’s primary conduit into an important intellectual circle that included key members of the Group of Seven and collectors Ruth and Harold Tovell as well as foreign cultural luminaries visiting Toronto, such as Walter Pach and Katherine Dreier. Brooker collected two of her works: Composition (Horses), c. 1927, and Composition (Reclining Nude), c. 1926–28. Munn also participated in the informal art classes he arranged. In 1935 Brooker was central to the organization of Exhibition of Drawings by Kathleen Munn, LeMoine FitzGerald, Bertram Brooker, at the Malloney Galleries in Toronto.

When Munn painted Untitled I, c. 1926–28—which was originally, with Untitled II, part of a larger canvas—it was among the first purely abstract works made in Canada. In Yearbook of the Arts in Canada, 1928–1929 (edited by Bertram Brooker), Frederick Housser wrote about Munn, echoing other critics’ assessment that Toronto audiences were not ready for her “advanced” art; he also inaccurately referred to her as a recluse.

Munn was a devoted modernist and read widely on topics ranging from the history and theory of art and design to poetry and philosophy. Her library included a wide selection: art books in English and also in Italian, German, and French (it is not known if she was fluent in these languages); several monographs on El Greco, Rembrandt, Ingres, Cézanne, Picasso, and Tintoretto; books on the Vatican and ancient art from Greece, Egypt, Byzantium, South America, Africa, India, and Asia; and a book on the anatomy of the cow. Her intellectual pursuits were complemented by her travels to Europe in the 1920s and 1930s and her repeated visits to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. These activities were foundational in her development as an artist.

The Passion Series

In the late 1920s Munn embarked on a meticulous process of experimentation, producing over a thousand drawings and sketches on the Passion of Christ—studies for ten large final works that are considered her most significant body of work. This process was a radical refinement in her artistic vision. After a nearly twenty-year commitment to the primacy of colour and painting, she focused almost exclusively on drawing and worked with black ink and graphite. Such continual experimentation and refinement are at the core of Munn’s work.

Whereas Christ’s Passion is canonical in European art, it was an unusual focus for a modernist in Ontario. What meaning did the Passion scenes have for Munn? Late in life she reflected, “The subjects for the pen and ink series came up irresistibly. I found my drawings suggested religious subjects from some depth in myself.”

The final works in Munn’s Passion series consist of eight large ink drawings from 1934–35 and two large graphite drawings from 1938. The drawings are the result of an intense and methodical process of her own that she devised and practised for years with rigour and perspicacity.

Munn drew six components of the Passion narrative: Last Supper (twice), Agony in the Garden, Christ’s Arrest, Crucifixion (twice), Descent from the Cross (twice), and Ascension (twice). She exhibited some of these along with other works on paper in 1935 at Malloney Galleries in Toronto in a group show with Bertram Brooker and Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald (1890–1956). She also displayed them on a few other occasions in the 1940s. In the spring of 1974, when curators from the National Gallery of Canada visited Munn, her walls were covered with these drawings. Indeed, these are the works Munn intended to be known for.

Art Abandoned

Munn gradually abandoned her artmaking around 1940, likely owing to a combination of events. For the first time, family duties distracted her from the studio. Also, now in her fifties, she suffered from cataracts and, more importantly, from a sustained lack of critical attention to her work. Although Munn had been included in two Group of Seven exhibitions, in 1928 and 1930, she was discouraged by the group’s dominance.

Munn’s artistic pursuits, rooted in New York modernism, differed from those of most of the Group of Seven artists, who were committed to a national art movement. This distinction is significant in why she has not played a more prominent role in Canadian art history. Although recognized in the twenties and thirties as one of the most “advanced” women artists in Canada, Munn remained on the periphery of the Canadian art scene. After she stopped making art, her work was largely forgotten.

In 1974 Charles Hill and Rosemary Tovell, two curators from the National Gallery of Canada (NGC), visited Munn in Toronto while researching the exhibition Canadian Painting in the Thirties. Subsequently, one of her final Passion series works was selected for purchase by the NGC. After decades of obscurity, Munn wrote of her hope: “a possible future for my work.” She did not live to see this happen. In October that year, before the sale was complete, she died, never knowing that her artistic achievements were soon to be recognized.

In the mid-1980s scholars and curators, led by York University professor Joyce Zemans, began the important process of recovering Munn’s work. The exhibition Kathleen Munn, Edna Taçon: New Perspectives on Modernism in Canada reintroduced Kathleen Munn and affirmed her contribution to the history of modern art in Canada. As a result of this touring exhibition and its accompanying catalogue, her work was soon sought after by important private and public collections across Canada. Since then a number of travelling exhibitions and catalogues have established Munn’s important role.

During her lifetime Munn sold or gifted very few works. Her only sale to an art museum took place in 1945 when the Art Gallery of Toronto (now Art Gallery of Ontario) purchased two of her drawings from the Passion series. No other works entered public collections until 1971, when the Art Gallery of Hamilton received a donation of her painting Mother and Child, c. 1930. Since very few of Munn’s works were collected privately, her family was left a comprehensive record of her artistic output. Her estate also included her extensive library as well as her rich and significant archives, now housed at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements