Joyce Wieland explored a wide range of materials, media, and subject matter in her work. Three major impulses dominate the evolution of her visual art: the legacy of painting, the emergence of a cinematic style as she experimented with filmmaking, and the adoption of traditional needlecrafts historically viewed as “women’s work.” In staging dramatic encounters between these three artistic modes, Wieland generated new forms of meaning and aesthetic pleasure.

Beyond Painting

Wieland began and ended her career as a painter: the artistic tradition remained important to her, even when she was not wielding a paintbrush. The paintings she first exhibited share qualities with the modernist abstraction of the Toronto group Painters Eleven and other international abstract art movements in the 1950s. However, by 1960 Wieland was already adding words, graffiti-like scribbles, and crudely drawn intimate body parts to otherwise abstract paintings, as well as cloth and assorted objects to her canvases. In other instances she drops in pop culture elements such as speech balloons to interrupt the terrain of abstract art, as in her 1963 work Stranger in Town. Thus Wieland sustained a dialogue with the legacy of abstract painting over a period of several years. She remained attentive to formal concerns but also playfully pushed the boundaries of what could be done to the painted surface. In this respect Wieland can be compared to the American artists Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008) and Jasper Johns (b. 1930).

Soon Wieland’s imagination would be taken over by cinematic paradigms, and then she not only made films but also allowed the logic of films to determine the shape and structure of her paintings. Some paintings are narrow and vertically oriented, mimicking film strips, as in First Integrated Film with a Short on Sailing, 1963. Other canvases are divided into grids and offer film-like narrative sequences, complete with jump cuts, close-ups, and other filmic devices, as in Boat Tragedy, 1964.

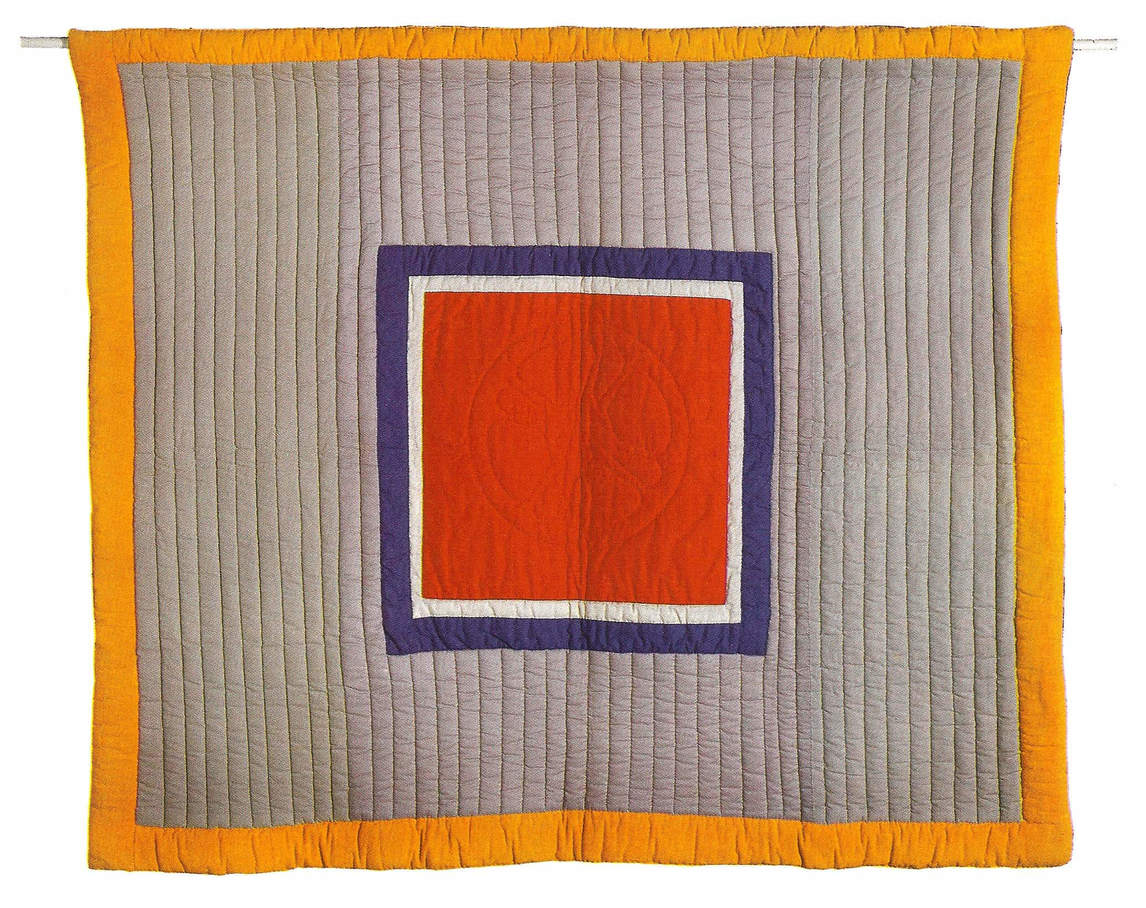

From the latter 1960s until the 1980s Wieland rarely painted, but she continued to engage with the medium’s influence in specific ways. Her quilts and plastic assemblages are hung on gallery walls, just like paintings. In one of her most striking fabric works, 109 Views, 1970–71, she parodies a mass of landscape paintings, each one with its own frame, in a monumental assemblage measuring over 8 metres in length. Shown as part of Wieland’s exhibition True Patriot Love at the National Gallery of Canada in 1971, this work illustrates her deep connection to Canada’s national tradition of landscape art.

When Wieland finally returned to painting later in life, she often depicted fantastical or imaginary landscapes. Her practice of painting on canvas was a mode of image making that remained integral to her vision over the years, even as she experimented with diverse materials and technologies.

The Impact of Needlework

In the 1960s and 1970s Wieland often incorporated sewing, knitting, quilting, and embroidery into her artworks—a radical decision for an artist at that time. These domestic skills are usually classified as craft, folk, or decorative traditions rather than art. The bias has deep cultural and institutional roots. What women traditionally did in the home tends to be undervalued, while museums isolate the great masterpieces of painting and sculpture (of course largely done by men), exhibiting them far away from supposed minor modes of material or visual culture. Wieland deliberately set out to reclaim this kind of “women’s work,” to acknowledge the skills, inventiveness, and shared knowledge embodied in a quilt or embroidered fabric.

While Wieland deliberately drew on traditional forms of needlework, she also brought these traditions into contact with twentieth-century artistic currents. Many of Wieland’s sewn and embroidered artworks prominently feature language, illustrating an affinity with linguistically based Conceptual art. Rather than replicating traditional samplers, Wieland included language in her art as a way to engage with contemporary political rhetoric. At times Wieland called attention both to the material properties of sewn artifacts and to the performative aspects of these traditions. Through “accidental” effects or close-up photos of stitches in the bookwork True Patriot Love, 1971, she exaggerates carefully sewn seams and loose threads to give the viewer a sense of an incomplete narrative.

Describing and labelling these polyvalent artworks is a challenge. The terms “fabric assemblage” and “quilted cloth assemblage” came into use to suggest that these are hybrid artifacts. As they engage with an avant-garde tradition of sculptural assemblage, Wieland’s artworks pay homage to domesticated folk traditions. In this regard she was on the cutting edge of feminist scholarship and artistic practice. The American artist Judy Chicago (b. 1939) used needlework as a political tool in her installation The Dinner Party, produced between 1974 and 1979, and it was not until 1984 that Rozsika Parker’s groundbreaking book The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine was published.

A Cinematic Style

During the 1960s Wieland sustained her visual art practice while branching out into experimental film. The exploration of cinematic framing, sequentiality, and narrative momentum was not limited to her actual filmmaking, though. She also set out to transfer these aspects of cinematic style to her visual art practice, making a range of paintings, assemblages, and fabric objects that in some way mimic or evoke films. During this period Jack Chambers (1931–1978) was also intent, in his own distinct way, on opening a dialogue between painting and cinema.

In 1971 the influential American film critic Andrew Sarris announced that “the talented Canadian Joyce Wieland leads the contingent of women film-makers in the experimental, abstract, poetic, avant-garde, underground categories.” Wieland achieved this reputation as she showed her films alongside those by other artists grouped around New York’s Film-Makers Cooperative, including Jonas Mekas (b. 1922), Hollis Frampton (1936–1984), Shirley Clarke (1919–1997), the Kuchar brothers (Mike, b. 1942; George, 1942–2011), Jack Smith (1932–1989), Flo Jacobs (b. 1941) and Ken Jacobs (b. 1933), and her husband, Michael Snow (b. 1928). Many of the films produced by these artists are short. They provide neither heroes nor romantic leads for the audience to emotionally identify with, and they frequently dispense with a narrative line.

Wieland has often been associated with the Structural film movement, whose practitioners concentrated on the material properties of film, projection, light, and camera movement, while generally avoiding narrative completely. Wieland was never a perfect fit with the Structural school, though, and the term “underground film” is perhaps as appropriate, in that films from this genre and era are often rooted in subcultural or countercultural social groups. Wieland was inspired by Jack Smith’s cheaply made Flaming Creatures, 1963, a fantastical vision of cross-dressing made by Smith and his friends. Engaging with both underground and Structural approaches to filmmaking, Wieland’s films unravel the material qualities of the cinematic image, while also introducing storylines related to politics, patriotism, sexuality, embodiment, and other themes of interest to the counterculture.

While Wieland was making films—such as Patriotism II, 1964; Water Sark, 1965; Hand Tinting, 1967; and Sailboat, 1967—she was also creating paintings, plastic assemblages, and quilts using diverse materials that transform and adapt cinematic language and technique. From 1963 onward many of her paintings are divided into frames that are read sequentially, implying both movement and narrative progression, even when the storyline is as rudimentary as the plight of a sinking ship, as in Boat Tragedy, 1964, or a romantic kiss, as in First Integrated Film with a Short on Sailing, 1963. These paintings often include cinematic devices such as frame-by-frame advances to a close-up, as if in a deconstructed zoom, and sudden shifts of perspective.

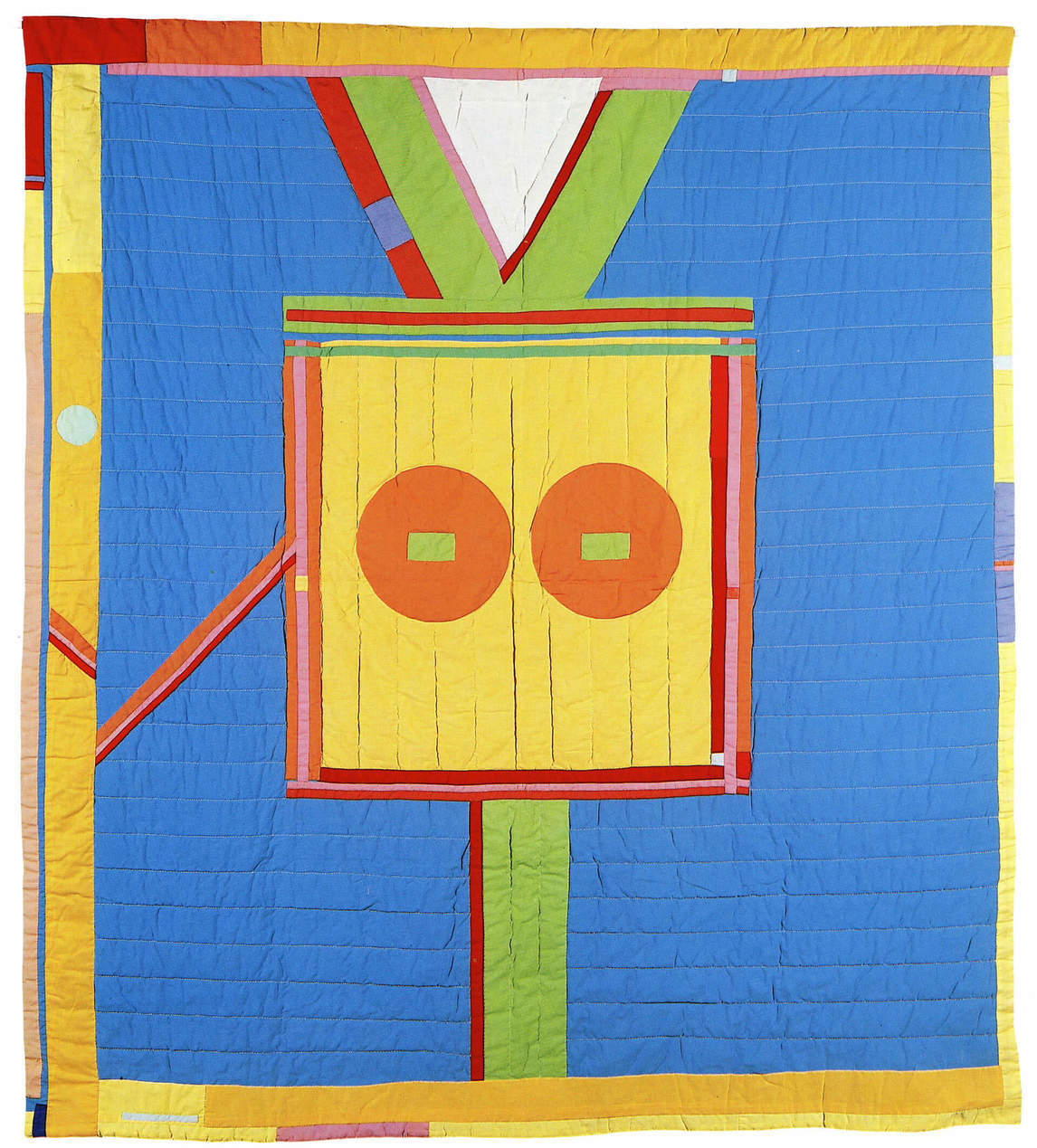

In 1966–67 Wieland made a series of soft hanging sculptures using plastic. These sculptures resemble vertical strips of film and are explicitly titled “film” or “movie,” as in Stuffed Movie, 1966. In the quilts she made in 1966, such as The Camera’s Eyes and Film Mandala, the familiar geometric aspect of traditional quilts now accommodates the square form of an old movie camera and the round shape of the lens.

The recurrence of cinematic motifs in Wieland’s art practice is a clear acknowledgement of the profound impact that movies had on all aspects of twentieth-century visual culture. By complementing her actual filmmaking with hybrid art forms that borrow aspects of cinematic experience, Wieland contributed to a new way of making art in the 1960s—between and across media.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements