Joyce Wieland (1930–1998) began her career as a painter in Toronto before moving to New York in 1962, where she soon achieved renown as an experimental filmmaker. The 1960s and 1970s were productive years for Wieland, as she explored various materials and media and as her art became assertively political, engaging with nationalism, feminism, and ecology. She returned to Toronto in 1971. In 1987 the Art Gallery of Ontario held a retrospective of her work. Wieland was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in the 1990s, and she died in 1998.

Early Years

Joyce Wieland was born in Toronto on June 30, 1930, the youngest child of Sydney Arthur Wieland and Rosetta Amelia Watson Wieland, who had emigrated from Britain. Her father’s family included several generations of acrobats and music-hall performers. Both her parents died before she reached her teens, and she and her two older siblings, Sid and Joan, experienced poverty and domestic instability as they struggled to survive. Showing an aptitude for visual expression from a young age, Wieland attended Central Technical School in Toronto, where she initially registered in a fashion design course. At this high school she learned the skills that later enabled her to work in the field of commercial design. It was also at Central Tech that she first came into contact with sculptors and painters, such as Doris McCarthy (1910–2010), with whom she studied. McCarthy, who was committed to her art and had an independent spirit and sense of style, became an important role model for Wieland.

Emergence as an Artist

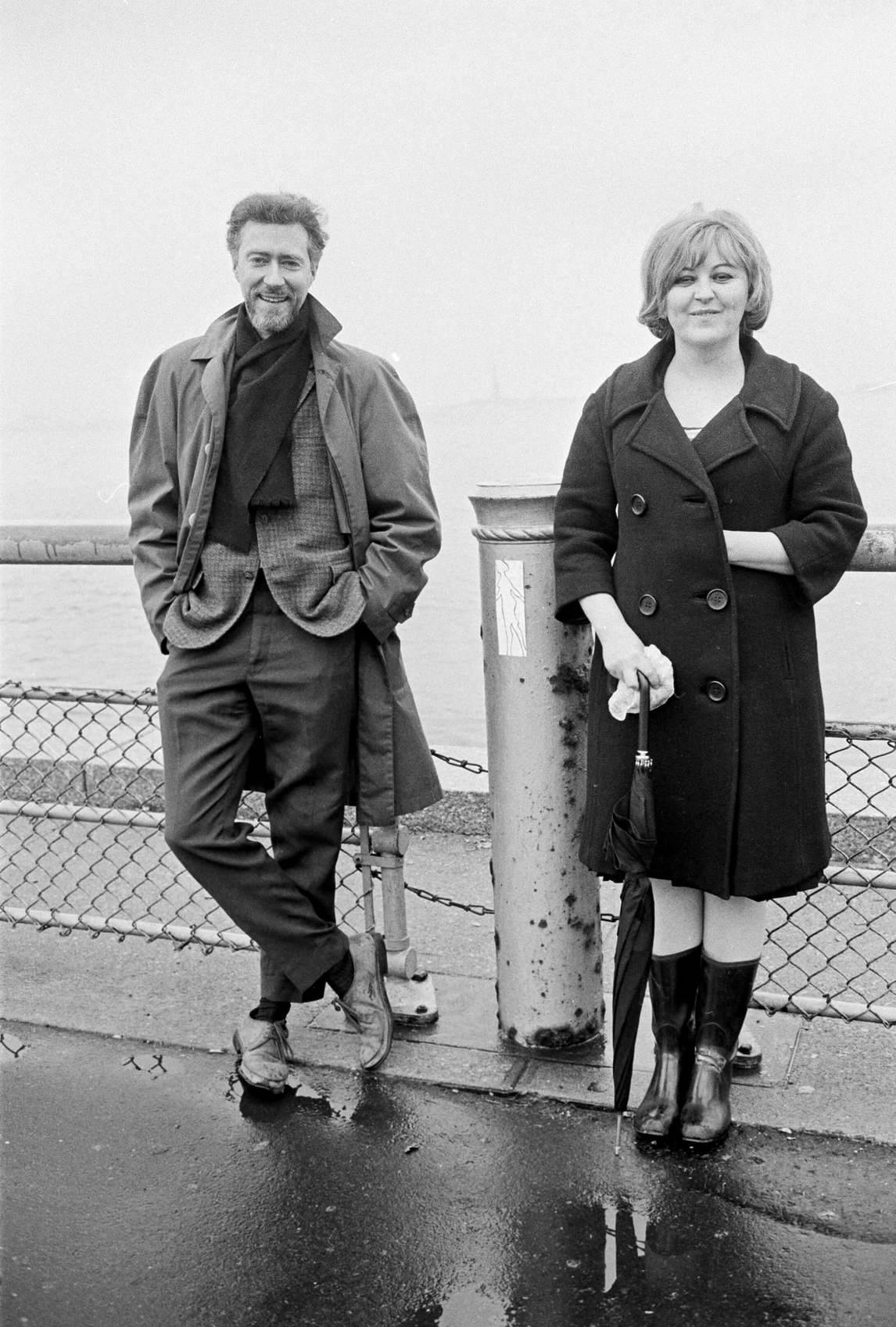

After graduating in 1948 Wieland worked as a graphic designer during the early 1950s, simultaneously developing her own art practice. She shared lodgings with friends but eventually moved into a studio space of her own in downtown Toronto, living independently at a time when that was not the norm for young women. She lived alongside other artists and became part of the city’s bohemian scene. In her early twenties she also travelled to Europe on a couple of occasions. By all accounts Wieland was tremendously vivacious and quick-witted, and she acquired many friends and admirers throughout her life. While employed at the firm Graphic Associates, which made animated and commercial films, she met fellow artist Michael Snow (b. 1928), who was also working there. Wieland and Snow married in 1956, and they remained together for over twenty years.

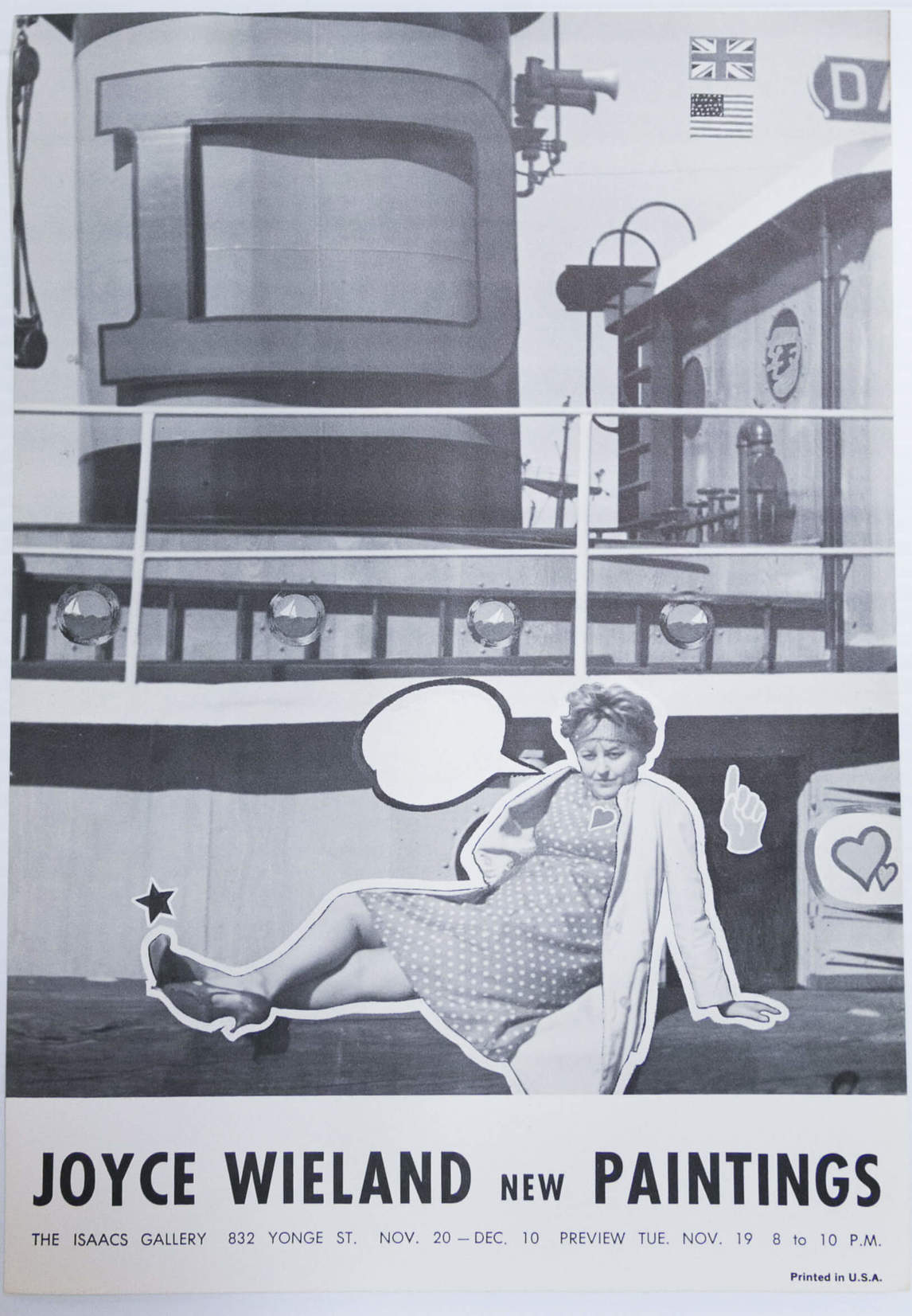

Wieland began to achieve success as an artist in the late 1950s, as part of group exhibitions, and she received her first solo show in 1960. Soon after, she began an affiliation with the Isaacs Gallery in Toronto, a relationship that continued for many years. Avrom Isaacs represented numerous prominent Canadian artists, such as Graham Coughtry (1931–1999), Gordon Rayner (1935–2010), Jack Chambers (1931–1978), Greg Curnoe (1936–1992), and Snow.

The New York Years

In 1962 Wieland and Snow moved to New York City, where they remained until 1971, living in adapted industrial spaces in lower Manhattan. The sixties were remarkably productive years for Wieland. She continued to paint, at least in the early sixties, while opening up her art practice to encompass a range of new materials and media.

Wieland’s work from these years shows how responsive she was to the period’s key artistic currents, such as Pop art and Conceptual art, though her interpretations of them were always original and idiosyncratic. Several coherent bodies of her work have emerged from this decade: quasi-abstract paintings that reveal messages, signs, or erotic drawings; collages and sculptural assemblages; filmic paintings; disaster paintings; plastic film-assemblages; quilts and other fabric-based objects; and language-based works. It was also during this period that she produced most of her experimental films.

At this point in Wieland’s artistic life, a rift developed between her visual art practice and her experimental film career. The New York gallery scene was a closed-off, exclusive world that she never broke into, and so her streams of paintings, assemblages, and mixed media works were exhibited back in Toronto (and elsewhere in Canada), while in New York she was part of a supportive and stimulating experimental film community. Even today her filmmaking is admired internationally, but her visual-art practice is barely known outside of Canada.

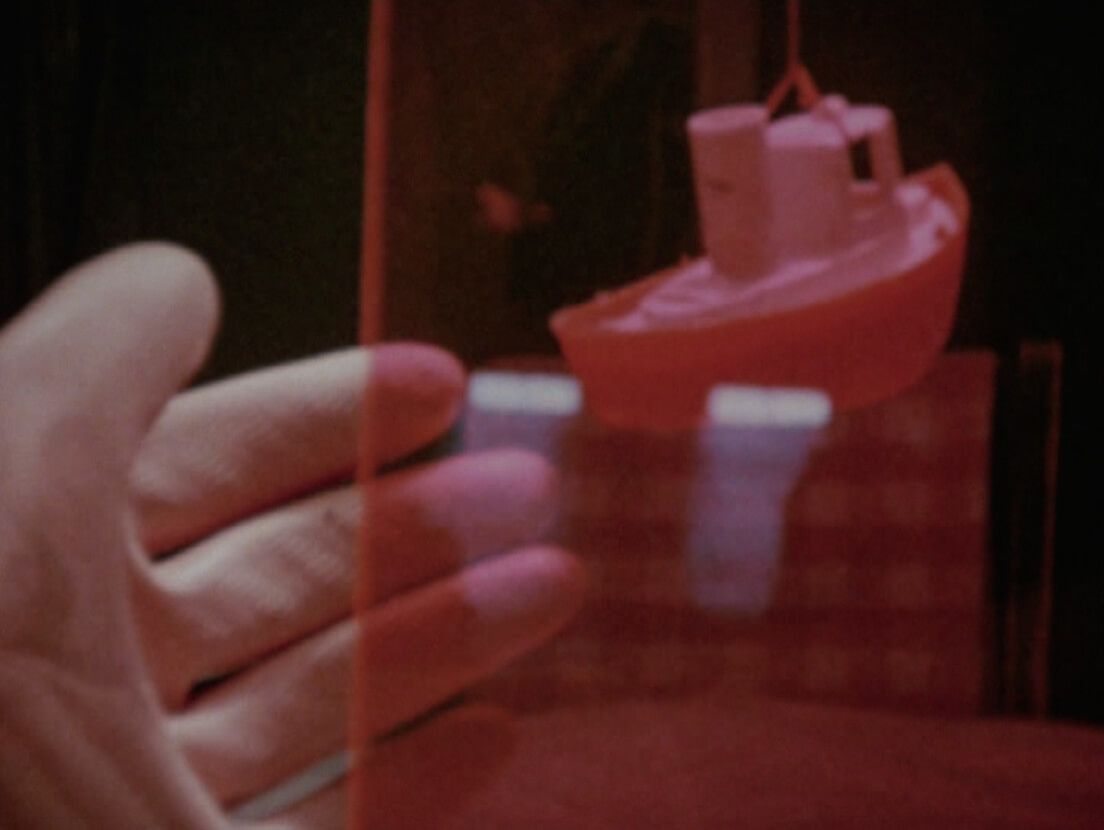

Wieland had learned filmmaking and animation techniques while working in the commercial-design milieu, so she was able to enter this field with confidence. In 1963 she began screening her films alongside those of American friends and collaborators such as Hollis Frampton (1936–1984), Shirley Clarke (1919–1997), and the Kuchar brothers (Mike, b. 1942; George, 1942–2011), as well as Snow. This initial exposure took place at informal screening sessions in New York organized by the critic and underground filmmaker Jonas Mekas (b. 1922) or others, but soon her experimental films were being shown at prestigious institutions (in 1968 the Museum of Modern Art in New York presented Five Films by Joyce Wieland, for instance) and international film festivals in France, Belgium, Germany, and elsewhere. Her films—such as Patriotism, Part II, 1964; Water Sark, 1965; Rat Life and Diet in North America, 1968; and Reason over Passion / La raison avant la passion, 1969—received considerable attention and were admired for their combination of formal rigour, political edge, and humour.

A Political Consciousness

During the 1960s Wieland also became more concerned with politics, nationalism, and activism. Like many others of her generation she joined collective actions to oppose the Vietnam War. She was ahead of her time in recognizing the importance of ecological issues, she was attuned to the racial injustices in the United States, and her espousal of feminist ideals also became part of an expanded political consciousness. While still living in New York Wieland began to follow political debates in Canada. In the late 1960s she was initially swept up in Trudeaumania, the wave of excitement generated by Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s rise to power. Just a few years later she was drawn to the radical, nationalist branch of the New Democratic Party, the Waffle, founded in 1969.

Life in New York during the 1960s was stimulating for Wieland at many levels, but the ideological orientation of the United States seemed to weigh heavily on her. She justified her eventual return to Canada by saying, “I felt I couldn’t make aesthetic statements in New York any more. I didn’t want to be part of the corporate structure which makes Vietnam.”

In 1971 Wieland was accorded a solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada, True Patriot Love, which opened on July 1, Dominion Day (now called Canada Day). It was the first time the National Gallery had given a solo show to a living Canadian female artist. Pierre Théberge—the exhibition’s organizer, the gallery’s curator of contemporary Canadian art, and later the gallery’s director—held Wieland’s work in high esteem, as did Jean Sutherland Boggs, the gallery’s director at the time, and its first woman director, serving from 1966 to 1976.

Wieland’s exhibition consisted of works that manipulated the symbols and familiar icons of Canadian nationhood: knitted maple-leaf flags; a small sculpture of a female figure with a beaver at each breast, titled The Spirit of Canada Suckles the French and English Beavers, 1970–71; an image of lips singing the national anthem; idiosyncratic landscape views; bilingual slogans. In addition various ephemeral elements were included, such as the massive, edible Arctic Passion Cake, 1971, and bottles of perfume called Sweet Beaver, which were for sale. She also created a bookwork, titled True Patriot Love, that accompanied the exhibition.

While not exactly a celebration of nationhood, True Patriot Love was a challenge to visitors to reconsider the terms of their nationalist commitment, and it deliberately contrasted Canadian and American sensibilities. And, even though this exhibition did not engage directly with the issue, Wieland was not oblivious to the rise of Québécois nationalism. Indeed, in 1972 she made an experimental film featuring the well-known Quebec writer and separatist Pierre Vallières. Through her artwork Wieland participated in a larger debate about national identity, though she was determined that her practice not be didactic in conveying a political position.

The Return to Canada and the Years Following

Soon after the National Gallery exhibition, Wieland and Snow left New York and returned to live in Toronto. Her political activism continued: she participated in protests against the building of a hydroelectric dam in James Bay, in solidarity with Cree inhabitants of the area, and she was also involved with the group Canadian Artists’ Representation (CAR, later CARFAC, with the addition of the French counterpart, the Front des artistes canadiens), which initiated the system of payment by institutions and organizations to artists for exhibiting or reproducing their artworks.

In the early 1970s Wieland’s creative efforts were largely marshalled into the making of a feature film, The Far Shore; she wrote the script, directed the film, co-produced it, and also spent a lot of time fundraising. When the film was released in 1976, some fans of Wieland’s experimental films did not know what to make of this melodramatic period piece, a kind of alternative history based on the iconic Canadian painter Tom Thomson (1877–1917) and his lover, an entirely fictional female character. The film is now appreciated for its innovative approach to gender and landscape and as a genuine experiment with genre.

The Wieland-Snow marriage broke up in the late 1970s. Wieland returned to painting in the 1980s, often devising hallucinatory imagery concerned with sexuality and spirituality rather than overtly political questions. In 1987 she was given a retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario. This exhibition provided a critical overview of her work, while synthesizing the two streams of her creative output: Wieland’s visual art production and her experimental films could be seen side by side.

In the 1990s Wieland’s health deteriorated, and she was eventually diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. A supportive community of women friends cared for her during her last years. Joyce Wieland died in Toronto on June 27, 1998.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements