From a background in design, Jock Macdonald turned to landscape painting soon after he arrived in Vancouver, and throughout his life he sought inspiration in nature. In the 1930s he embarked on a lifelong search for a personal abstract expression. His work developed through three distinct styles—the semi-abstract “modalities” of the 1930s, the automatic paintings of the 1940s, and the mature abstract paintings of the 1950s. These stylistic shifts, each one the result of a “breakthrough” experience and what Macdonald called “stepping stones,” occurred about ten years apart, precipitated by either a new source of inspiration or a new technique.

Design and Illustration

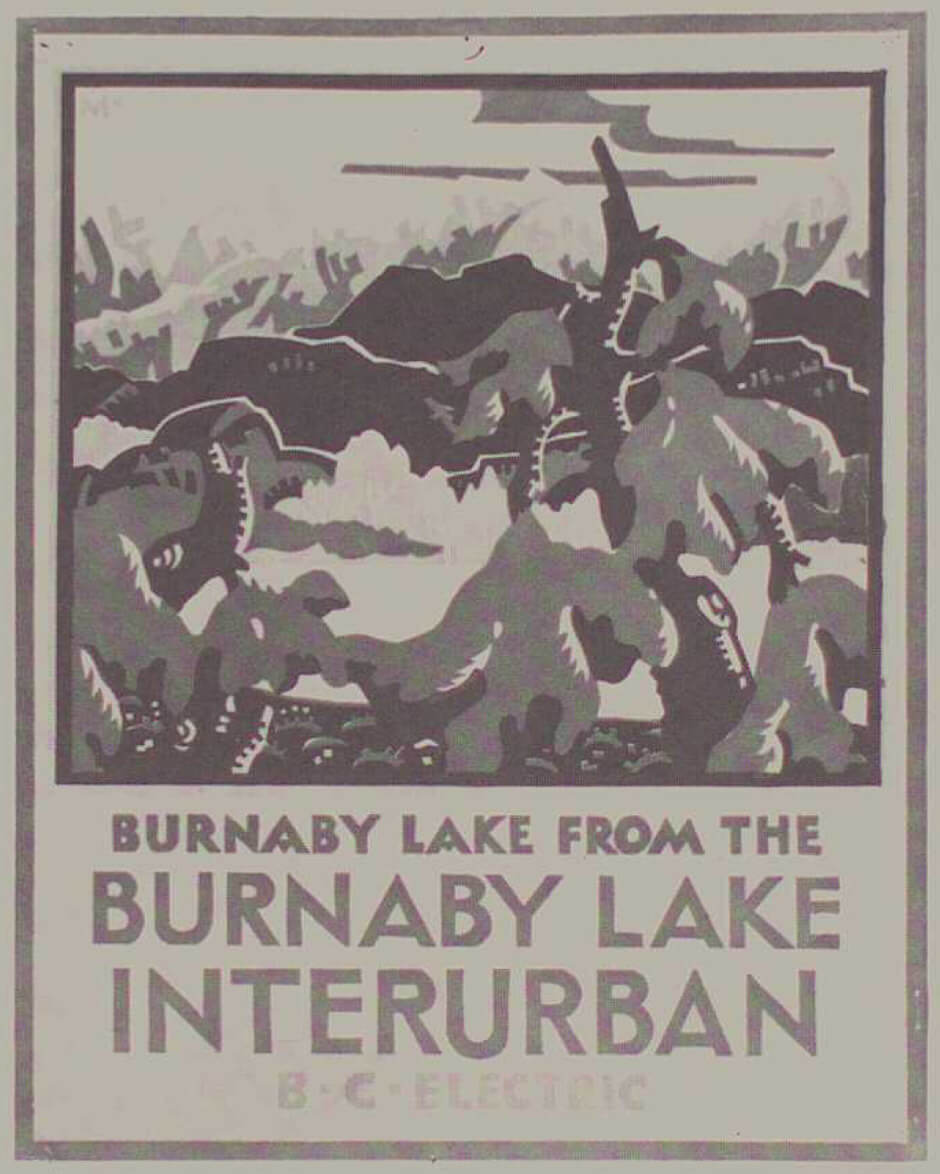

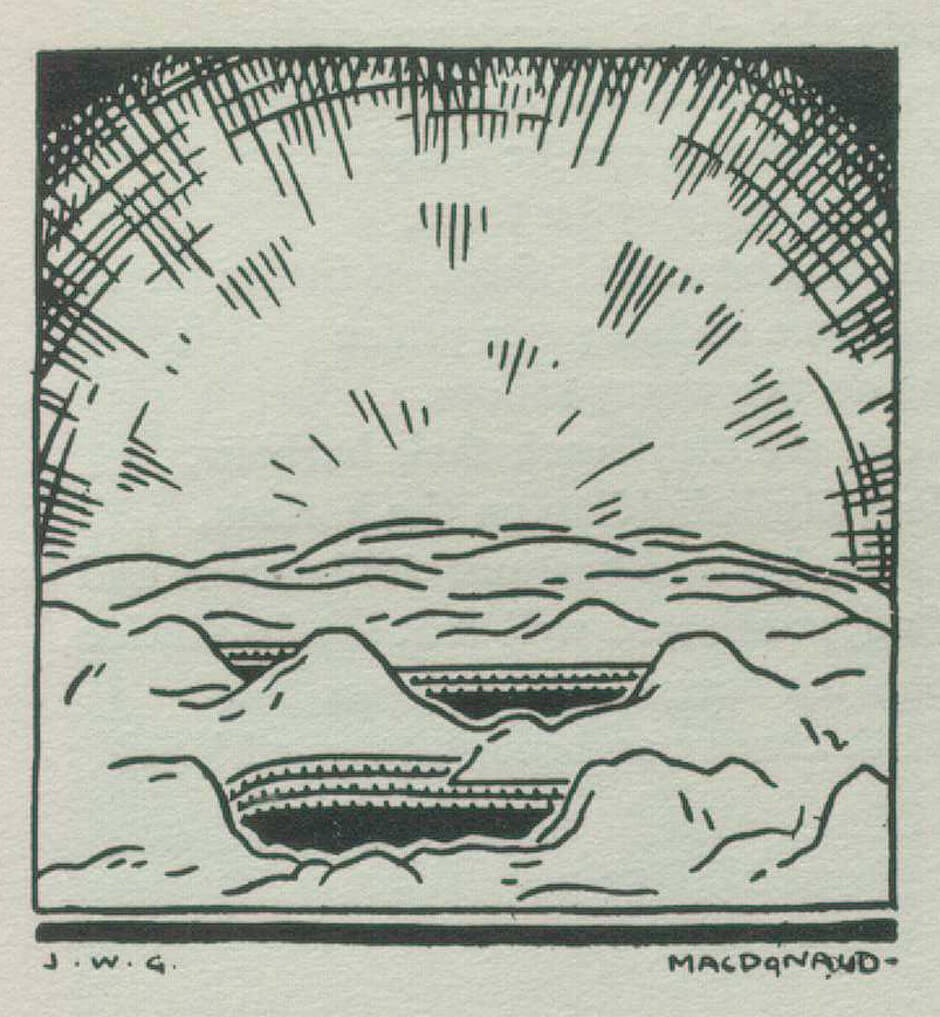

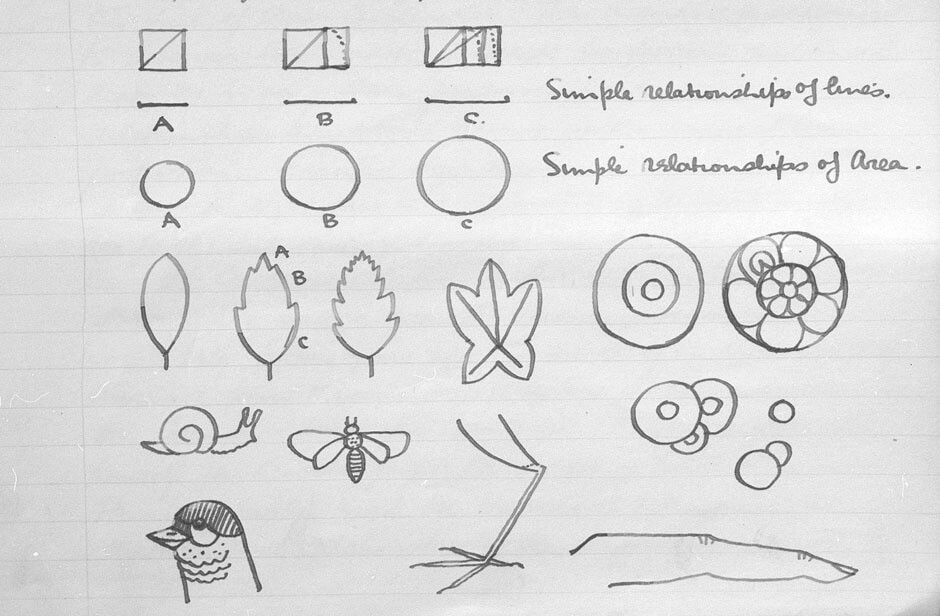

Macdonald’s art was rooted in his design education at the Edinburgh College of Art in Scotland and his three-plus years working as a designer at Morton Sundour Fabrics in England. Throughout his career in Canada he taught design at art colleges in Vancouver, Calgary, and Toronto. Not surprisingly, core design principles dominated his early work as a successful illustrator, as in Burnaby Lake, c. 1929. When he transferred his artistic attention to landscape painting and abstraction and tried to loosen his paint handling and surface patterning, his training as a designer became a handicap he sought to escape.

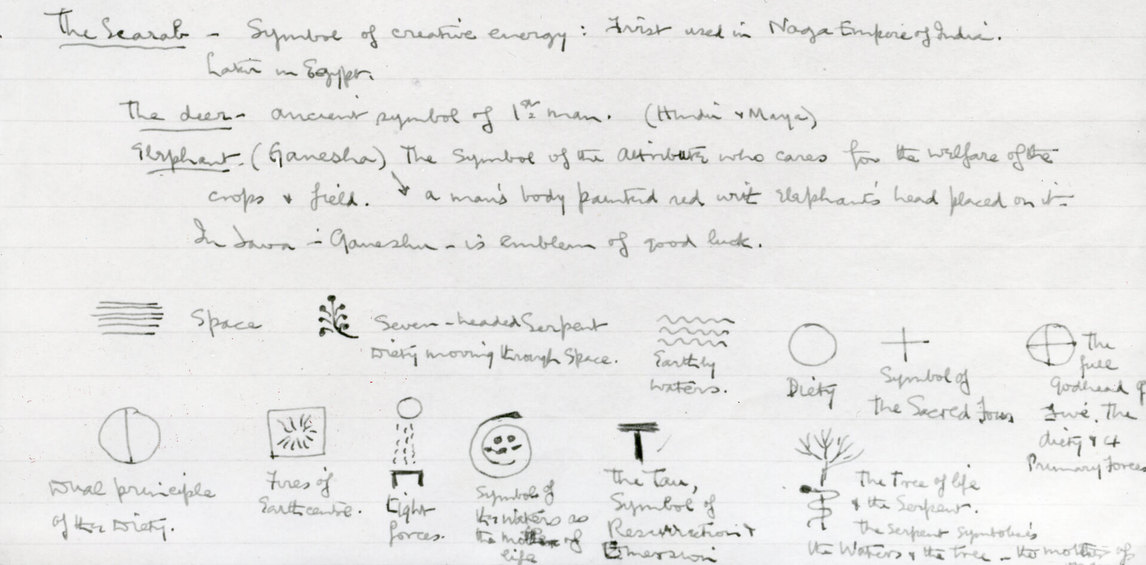

The teaching notes Macdonald prepared for his courses in design reflect his belief in two fundamental ideas. First, the designer must appreciate certain core principles and symbols that are reflected in the history of all cultures. Understanding the evolution of those symbols and their iconography is critical to successful design. Second, “knowledge of form and drawing is the foundation stone of Design.” A student, he believed, “must extract all there is to know about any one of God’s creations and then put down his observations in his own way. This is the only way to create original design.”

In 1929 Macdonald entered a competition to design a poster for the B.C. Electric Company. The subject, Burnaby Lake, was one his first B.C. landscape images. Macdonald’s skill as a designer is clearly evident in this poster. The flat, stylized, and decorative design suggests the influence of his teacher Charles Paine, the head of applied arts at the Edinburgh College of Art, who in the 1920s created posters for the London Underground Group. Exquisitely designed, the image is Art Deco in style: the foreground branches are set against snow-capped mountains and an abstracted pattern in the sky. Though an attractive and successful poster, it has none of the elemental power that characterizes Macdonald’s later landscape paintings.

Landscape Painting

Macdonald became close friends with Fred Varley (1881–1969) soon after they arrived to teach at the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts (now the Emily Carr University of Art + Design) in 1926. They often went on painting expeditions together to the Fraser Canyon, Garibaldi Park, the Rocky Mountains, and the Gulf Islands. Varley became Macdonald’s mentor and influenced his early evolution as a painter of the Canadian landscape.

As a youth in Thurso, Scotland, Macdonald had done plein-air sketches, primarily in watercolour. Varley persuaded him to experiment in oil to better capture the powers of the landscape and advised him to “stop drawing and start painting.” Macdonald later wrote: “The line and decorative forms were also forcing themselves too much … I can see what my wife and Varley meant when they said I was producing coloured drawings.” Macdonald gradually gained confidence: when he completed Lytton Church, B.C., 1930, he did not show it to Varley for his approval.

Macdonald’s magnificent mountain image The Black Tusk, Garibaldi Park, B.C., painted two years later, would be successful both nationally and internationally. In 1934 Macdonald returned to Garibaldi Park to paint the The Black Tusk again, this time in a much more ethereal manner. For Macdonald, like Varley, the challenge was to paint work that spoke to the unique character and spiritual power of the B.C. landscape.

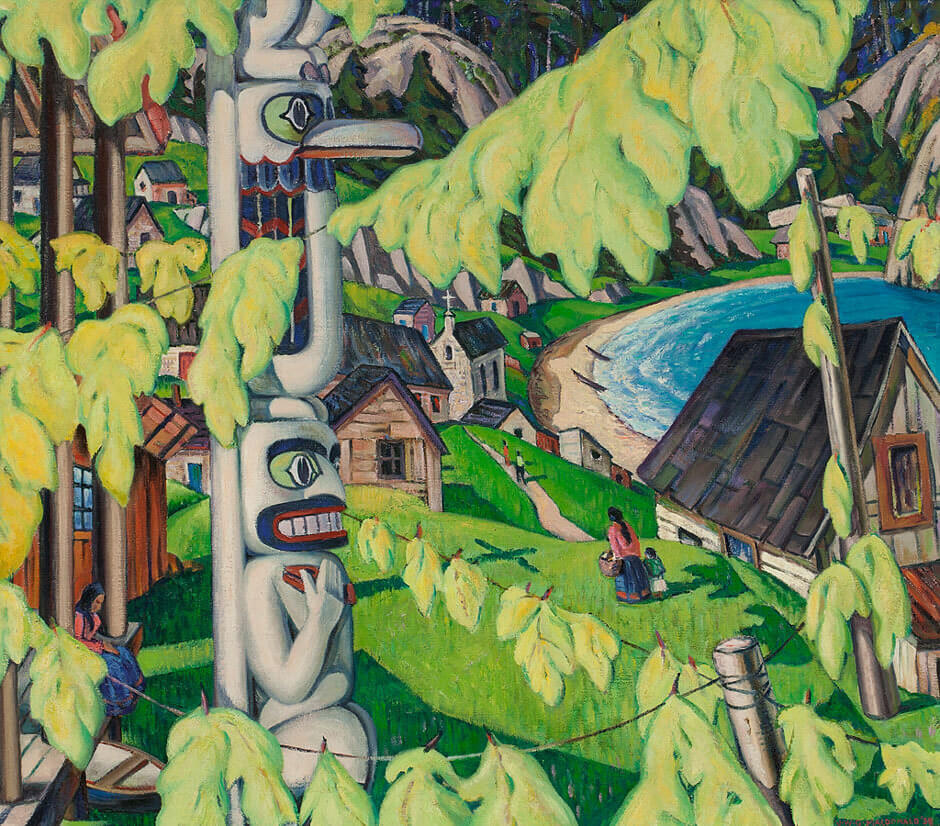

During his sojourn at Nootka from 1935 to 1936, Macdonald experienced first-hand the power of nature in his expeditions on land and his regular—and often difficult—navigation of the sea. Most of the works he completed there were oil-on-board paintings, many of which he sent back to Vancouver for sale. He completed only one major painting—Friendly Cove, Nootka Sound, B.C., 1935—a dramatic representation of the First Nations (Mowachaht) village at Yuquot. In this work, Macdonald, like Emily Carr (1871–1945), sought to convey the power of the totem pole, contrasting it to the tiny church in the far distance. When he returned to Vancouver, Macdonald worked several of these subjects up into strong paintings such as Indian Burial, Nootka, 1937, and Drying Herring Roe, 1938, in which he portrayed the spirit of Nootka and its life.

Macdonald’s stylistic approach would evolve, but landscape and direct contact with nature remained a constant source of inspiration. His friend Nan Cheney (1897–1985) wrote: “[Jock] is planning to go to Garibaldi in Aug…. This country has barely been touched & Macdonald is keen to go north or to the West coast of the island again—for two years—his health is much improved and if he could only get someone to finance him to the extent of $60.00 to $75.00 a month he would be off at once.”

In the early 1940s, after Lawren Harris (1885–1970) settled in Vancouver, he and Macdonald went on painting excursions together, most often in the Rocky Mountains. Macdonald found drama and spiritual power in the glaciers and the mountain spires. He called the Okanagan Valley “the real ‘Van Gogh’ country, with its strong lights, sage brush, sunbaked hillsides and brilliant colours.” Even after he left Vancouver in 1946 for Calgary, Macdonald would return during the summers, painting in the interior of British Columbia.

By then, however, Macdonald had essentially changed direction: “I am fairly certain that I won’t do any more landscape canvases,” he wrote. “Sketches yes, but to do a landscape canvas seems a waste of time + too much manufacturing.” The search for a personal abstract expression had become his principal focus.

Exploring Abstraction

Macdonald was familiar with European modernism from his student days, when he frequented the London galleries and found inspiration in the work, among others, of Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) and Paul Cézanne (1839–1906). From the time of his arrival in Vancouver, he attended discussions at the Vanderpant Galleries about contemporary artistic, mathematical, and scientific theories. The attendees had read Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1912) by Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) and were inspired by the ideas of Canadian artists Bertram Brooker (1888–1955) and Lawren Harris (1885–1970), among others. At the British Columbia College of Arts, theosophy, anthroposophy, and the interrelationship of the arts underpinned the curriculum.

In 1934 Macdonald painted the abstract Formative Colour Activity—a breakthrough work in British Columbia at the time. The close-up view was most certainly inspired by the photographic experiments of John Vanderpant (1884–1939). Macdonald’s personal notebooks and teaching notes and his 1940 lecture “Art in Relation to Nature” reveal that his exploration of abstraction resulted from a deep commitment to a personal artistic expression that embodied “the force … to which the whole universe conforms.” His objective was to “express the consciousness of the time in which [the artist] lives.” As he wrote, “To be creative, truly creative, one … must speak in the idioms of the time in which one lives.”

In the fall of 1936, just before leaving Nootka to return to Vancouver, Macdonald recorded a “breakthrough” in his painting—the result was a dramatic return to abstraction. His diary notes describe the creative process through which he painted both Departing Day, 1936, and Etheric Form, 1936. On October 5 he wrote: “I discover at last a new expression for painting—made four pencil notes for sketches + feel quite excited.” The next day, he painted “the first subject…. Only the abstract forms are used but they are intermixed in a bold mass. Purest colours are used + give a brilliant value.”

On October 24 Macdonald recorded three more experimental sketches that he said were “memories of dreams.” Pilgrimage, 1937, painted after his return to Vancouver, may have been one of these dream images. In this work, two Nuu-chah-nulth canoes in the foreground provide a link to the lived experience of Northwest Coast Indigenous cultures, but the rest of the painting represents an abstracted dream landscape. The scene is penetrated by descending rays of light as the trees arch to create a natural sanctuary with a central pathway.

Over the next decade, while he continued to paint representational works, Macdonald became increasingly preoccupied with what he called his “modalities” or “thought idioms in nature.” He likely discovered the term modalities in The Foundations of Modern Art (1931) by Amédée Ozenfant (1866–1966), though he expanded his definition (“typical forms of feeling and thinking”) to include the theories of time and space as described by P.D. Ouspensky (1878–1947) in Tertium Organum: The Third Canon of Thought, A Key to the Enigmas of the World (1922).

When Lawren Harris returned to Vancouver in 1940, he found a kindred spirit in Macdonald, and he encouraged and championed Macdonald’s abstract work. Though Macdonald, in later years, would sometime refer to his art as “non-objective,” it was Harris’s definition—“painting abstracted from nature”—that best described Macdonald’s guiding principles in the creation of his modalities. Harris wrote in Abstract Painting: A Disquisition (1954) that this type of art is based on an idea and that “the meaning dictates the forms, colours, aesthetic structure and all the relationships in the painting, the purpose being to embody the idea as a living experience in a vital plastic creation.”

Automatic Painting

![Art Canada Institute, Jock Macdonald, Untitled [10.20 p.m., September 16, 1945], 1945](/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/art-books_19_jock-macdonald-untitled-1945-contextual.jpg)

Macdonald was introduced to automatic painting in April 1944 by the British Surrealist artist and psychiatrist Grace Pailthorpe (1883–1971) and her colleague, artist-poet Reuben Mednikoff (1906–1972). In the fall of 1945 he became their pupil and under their supervision worked intensely on a series of exercises for three months. Examples in the Pailthorpe archives show that Macdonald completed at least twelve automatic images on his first day of study and fourteen on his second. Each was meticulously dated and timed. Some have notations by Pailthorpe or by Mednikoff, commenting on technique and offering examples of how he might, for example, loosen his style, find the hidden meaning in the works, or extrapolate imagery such as birds or fish suggested by those abstract marks.

Beginning with monochromatic ink washes and pencil drawings and eventually moving on to colour pencil, watercolour, and combinations of media, Macdonald progressed from single concentrated images to fully developed and elaborate watercolours—often on wet paper to increase the fluidity of the painting. Many of these exercises are circular in composition, drawing the viewer into the image. Pailthorpe attributed their success to this mandala framing device.

Pailthorpe believed that through free association, when the mind is not interfering with what the hand is creating, artists could gain access to the subconscious and its reservoir of archetypal images, and that art should be capable of expressing the universal human condition. To be successful, however, art had also to embody aesthetic values including rhythm, balance, form, and pattern. Without these qualities, she said, there would be little pleasure in such creations.

![Art Canada Institute, Jock Macdonald, Untitled [October 26, 1945]](/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/art-books_19_jock-macdonald-untitled-automatic-drawings-1945-contextual.jpg)

Macdonald, like the Abstract Expressionists Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), Adolph Gottlieb (1903–1974), and Arshile Gorky (1904–1948) in New York, welcomed automatism as a way to find inspiration in the subconscious. Late in his career Macdonald wrote: “Automatic art, for me, is a reflection of one’s experiences in life as all that one has observed is retained in the deeper inner mind, and in Automatic art one is painting imaginatively one’s impressions of nature.”

Macdonald continued practising automatic painting for the next ten years, introducing it to his students and incorporating it into his teaching as well. Describing the impact of Macdonald’s teaching, Calgary artist Marion Nicoll (1909–1985) recalled:

He really roused things up. In Jungian theory you forget absolutely nothing … sight … sound … it’s all stored in your subconscious. It is stored there in its true form, not colored by personal bias of any kind. It is a source of Information; you put your hand down, you watch, and you wait. Look, look! there it goes! I’ve made things that would make your hair stand up—birds, forked tongues, and male and female mixtures. I don’t think I ever would have been an abstract painter if I hadn’t gone through 1946–57 with automatic drawing.

For Macdonald, himself, automatic art became a crucial aspect of his artistic practice. He wrote to Pailthorpe and Mednikoff in 1948: “I am working every chance I can (four or five nights a week) on watercolours + black and white in our little kitchen.” Colin Graham, the director of the Arts Centre of Greater Victoria (now the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria), described the process: “Barbara would turn on the radio and Jock would just start fooling around with the watercolours … I gather it was helped by Barbara who kept his conscious mind [away from the painting] so that the automatic process was really working and he would keep talking to Barbara and still dream.”

In many of these paintings the tightness of the line drawings of animals, people, and imaginary creatures extrapolated from the abstract markings seems to contradict the openness of his painterly style. Macdonald the designer continued to struggle with the temptation to exaggerate the linear embellishments that interrupt the flow of the work. In Orange Bird, 1946, for example, the design and decorative, almost cartoonish elements dominate, but in the beautiful Phoenix, 1949, the image evolves from the paint itself in an entirely coherent and satisfying automatic painting.

Macdonald’s crucial challenge lay in translating the freedom, elegance, and spontaneity of these watercolour automatics to a large format in the more demanding and slower medium of oil. His first automatic oil, Ocean Legend, 1947, though well received, illustrates the problems he encountered, and the composition remains locked in a cubist-derived grid. He himself wrote, “Truthfully, I am not altogether satisfied with it—not enough depth in it + a bit too busy.”

In the summers of 1948 and 1949, Macdonald studied in Provincetown, Massachusetts, with Hans Hofmann (1880–1966). Both men believed that all art, even non-objective art, had to begin with nature. Hofmann, Macdonald wrote, “valued automatic expression as the essence of creative work.” In paintings such as Black Evolving Forms, 1953, Macdonald would be influenced by Hofmann’s theoretical approach to abstraction—“his spiritually poised concepts of plastic-space creative art [the ‘push-pull’ theory of the surface].” Hofmann praised Macdonald’s automatic work in watercolour, saying he should devote the rest of his days to painting. Macdonald wrote: “After the direction I received from Hofmann I feel that my oils are weak efforts but something will happen before long.” It would be almost a decade, however, before Macdonald discovered the solution to his problem with oils.

Non-objective Painting

In 1954 Macdonald became a senior member in the formation of Painters Eleven, the group of Toronto-based artists who banded together to exhibit and promote abstract art. A year after the group’s formation, Macdonald observed: “The ‘established artists’ in Toronto … would love to abolish us. This they cannot do as the inner spark in this group is amazingly united in purpose and holds a common faith in one another.” Encouraged by his colleagues’ commitment to abstraction, the quality of their work, and their engagement with the most contemporary developments in art internationally, Macdonald continued to struggle to find a way to translate the fluidity of his watercolours into oil. With the support of Painters Eleven, Macdonald embarked on the last stage in his artistic evolution.

In the spring of 1955 during his sojourn in France, Macdonald met Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985), whose work he greatly admired. Dubuffet advised him to add turpentine and linseed oil to his paint and to use long, pliable brushes. “It is only a technique discovery you have to find,” he said. “Everything else you have already.” Macdonald noted: “If I should find my way, then certainly Dubuffet will be given the credit for a change in my oils—I will see to that.”

In the summer of 1956, a year after his return from Europe, Macdonald was able to devote himself to painting once again. His colleagues introduced him to pyroxylin, an industrial gloss enamel paint marketed under the trade name Duco, which Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) had used for its fluid, quick-drying properties. Its odour was noxious, but Macdonald persevered in using it, despite having previously had lung problems. He had finally found a fluid medium that allowed him to work on a larger and more dramatic scale. Ray Mead (1921–1998) remembered Macdonald painting in rubber gloves, with his studio window flung wide open.

Though Macdonald used Duco for only eight months, it provided the liberation he had sought for so long. He wrote: “I have been exclusively experimenting in plastic [Duco] paints all summer…. The chief gain [over] straight oil techniques is the speed with which one must work and with the rapid drying. Also, of course, the fluid quality…. I find my work far freer—much less tight, more painterly and frankly, I think, more advanced. In winter I will not continue this medium as I could not stand the odour.”

Obelisk, 1956, is one of those paintings in Duco. Perhaps to compensate for the flatness of the new medium, Macdonald mixed sand into the ground of this work. The painting’s limited colour scheme contrasts dark and light, negative and positive elements, as the flattened shapes overlap and intersect. The central vertical image, by its sheer mass, dominates the composition, allowing Macdonald to achieve a carefully calculated monumentality. Macdonald would continue to paint in oils during this time, but the medium could not offer him the same flexibility as the plastic paint.

A year later, when Macdonald began to work in Lucite 44, he made his final breakthrough. This acrylic, fast-drying, and fluid paint finally permitted him to work on large canvases, such as Desert Rim, 1957, and to translate the brilliance of his watercolours to the oil medium. After three decades as a painter, Macdonald felt he was really “finding his stride.” Combining Lucite with oil, his painting became “far freer, much less tight, more painterly and more advanced,” he told Pailthorpe—qualities he had been searching for since he first began to paint. “Now that I have found my way—completely my own way—I am now painting continuously through my free moments from teaching.”

Macdonald was also buoyed by the encouragement he received from the American art critic Clement Greenberg (1909–1994). In August Macdonald wrote to Maxwell Bates (1906–1980) that he found his work “altogether different from anything I have ever done and … far superior…. Greenberg gave me such a boost in confidence that I cannot remember ever knowing such a sudden development taking place before. The only parallel was when I concentrated for 5 months producing automatic watercolours every day. This work is also automatic–non-objective but not like anyone else’s stuff.”

In the fall of 1959 Macdonald painted a series of magnificent yellow canvases. He described these works as “soft, delicate and airy.” In Young Summer, 1959, the yellow ground shimmers and coalesces with the figures scattered across the surface in vibrant interrelationships. It is difficult not to think of the microscopic slides of acid drops that Macdonald projected for his students during these years—a “slide of acid drops that resembled butterfly wings and suggested beautiful imagery as subject matter for paintings.” Like the Nootka modalities, these works speak to the spiritual in nature—to its essential structure and character—and to the creation of a new form of art that represents its own time.

The apparent ease and fluidity of the canvases of his last years—such as Airy Journey, Flood Tide, and Iridescent Monarch, all 1957; Contemplation and Legend of the Orient, 1958; Heroic Mould, Fleeting Breath, and Fugitive Articulation, all 1959; and Nature Evolving, All Things Prevail, Far Off Drums, and Growing Serenity, all 1960—is breathtaking. Macdonald wrote to his former student and friend Thelma Van Alstyne (1913–2008): “Non-Objective masterpieces are created intuitively—are alive with spiritual rhythm and organic with cosmic order which rules the universe.” Recognized for their brilliance by Canadian and American critics alike, the paintings are unique in the history of mid-century abstraction.

Bates summed up Macdonald’s career best: “The explorer of ideas, when a painter, cannot accept a safe career by early finding a suitable style. Instead he makes his way beyond the region mapped and appreciated by the art-interested public. The explorers are not only the most creative artists, they contribute most to the art. Their trials and tribulations come early; success often comes late. Jock Macdonald is such an explorer of visual ideas.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements