Jock Macdonald was a leading pioneer of abstract painting in Canada. Committed to the belief that contemporary art had to be based on “20th-century concepts about nature, space, time and motion,” he became a staunch advocate for contemporary artistic expression. He was a founding member of the Canadian Group of Painters and Painters Eleven, and he established the Calgary Group. A dedicated teacher, he was a role model and mentor to several generations of artists in British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario. As an artist, teacher, and activist, he had a profound influence on Canadian art.

Artist-Philosopher

Throughout his life as an artist, Jock Macdonald was engaged in a search for new forms of beauty. As he wrote to H.O. McCurry in 1937, “I have been searching for a new expression in art…. To fail to follow through the force which is driving me— + which I clearly believe is a true creative art—would be destruction to my soul.” Guided by current theories of art and aesthetics, science and mathematics, he sought to create paintings in which the spiritual nature of the universe would become evident. His search was for an artistic expression that embodied an “aware[ness] of the new space consciousness of our time, the psychological reactions to vibrant colour and the dynamic force of modern composition.”

In the late 1920s and 1930s in Vancouver, the spiritual in art and the artist’s search for the “universal centre” were, along with contemporary artistic expression and the interrelationship of the arts, regular topics of discussion at the weekly Vanderpant musicales that Macdonald attended. There the photographer John Vanderpant (1884–1939) presented lectures, slide shows, and recordings focusing on the work of contemporary artists and musicians. His talks focused on modern art, including the Group of Seven as well as European modernists such as Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), Amédée Ozenfant (1866–1966), and Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), and composers largely unknown to his audience. By the early 1930s Vanderpant was experimenting with photographs of imagery abstracted from nature—Heart of the Cabbage, c. 1929–30, for example—that he called “thought-expressions.” This term likely derived from the “thought-forms” that the British theosophist Annie Besant (1847–1933) wrote about in her search to understand the mysteries that united the universe, the divine, and humanity.

Fred Varley (1881–1969) had begun to explore Buddhism and Eastern mysticism, as is clear in his portrait Dharana, 1932, while members of the Vanderpant group were reading “Revelation of Art in Canada” (1926) by Lawren Harris (1885–1970)—who was increasingly drawn to theosophical concepts in his art. Artists also read Bertram Brooker’s syndicated column on contemporary art that appeared in The Vancouver Daily Province from 1928 to 1930 and the inaugural 1928–29 Yearbook of the Arts in Canada, edited by Brooker (1888–1955), in which he reinforced the idea that art should be contemporary and reflect the time in which it was created.

In his seminal public lecture “Art in Relation to Nature” at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1940, Macdonald argued that pictorial form must reflect the current understanding of reality. He cited Albert Einstein and the work of artist-theorists such as Kandinsky, who argued in Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1912) that the concept of matter was being replaced by “the theory of electrons” or “waves in motion.” Macdonald summed up the objectives that had guided him ever since his earliest exploration of abstraction in 1934—and which would continue to shape his credo:

Art is not found in the mere imitation of nature, but the artist does perceive through the study of nature the … one order to which the whole universe conforms. Art … is trying to tell us something, something about nature, something about the universe, and something about life.

… Art now reaches the place where it becomes the expression of ideals and spiritual aspirations. The artist no longer strives to imitate the exact appearance of nature but, rather, to express the spirit therein.

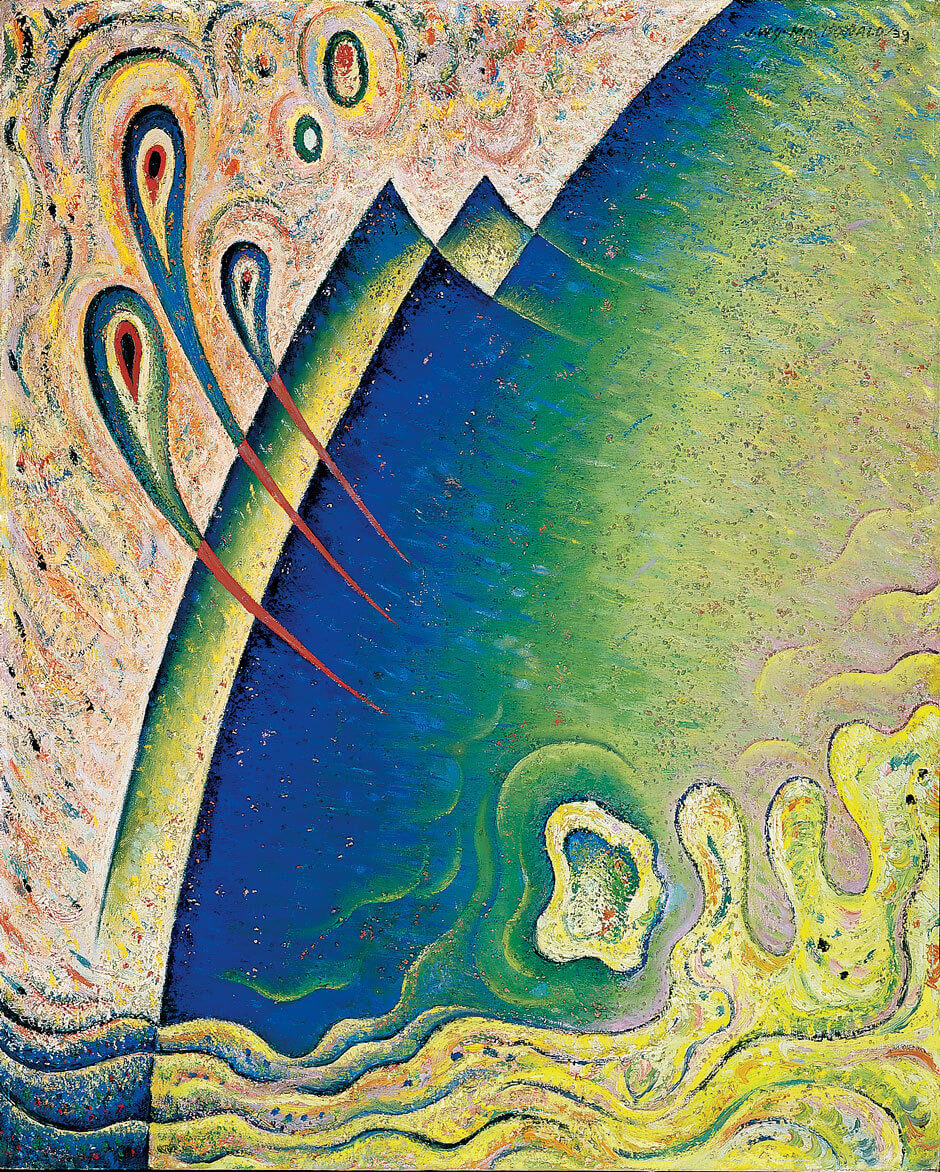

Troubled by the Depression and the political situation in North America and Europe, Macdonald sought to embody a higher order in his art. His search was for a “universal language” of art. He wrote to H.O. McCurry, director of the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, about his abstractions from the late 1930s such as Rain, 1938, and The Wave, 1939:

The “modalities” are thought idioms of nature—not completely geometrical, but containing a nature form in abstraction…. It means the same as saying the 4th dimension is an extension of the 3rd dimension; it contains an essence of the 3rd but has a different space & a different time, & through its added value of motion, it is an entirely new dimension. And the awakening of a new consciousness will arise out of the new knowledge from the slow understanding of the 4th dimension. For me, abstract & semi-abstract creations of pure idiom are statements of the new awakening consciousness. Thus I have more than a surface interest in the experiments I make on the extension of nature forms.

Macdonald continued to build on these ideas to guide his approach to painting. In his letters to McCurry and to Maxwell Bates (1906–1980) in Calgary, he took pains to describe his philosophy in detail. In the introduction to an exhibition catalogue for the Willistead Gallery (now the Art Gallery of Windsor) in 1954, he reiterated his basic principles:

Art … must seek to discover new forms of Beauty.

… Art is an expression of man’s consciousness.

The Artist should endeavour to express the consciousness of the time in which he lives.

Only through this search can new forms of Beauty be discovered.

The 20th Century art expressions are formulated on man’s new concepts about nature, space, time and motion.

… To be creative, truly creative, one cannot add anything to enrich the art of past centuries but must (try to) speak in the idioms of the time in which one lives.

Pioneering Abstract Artist

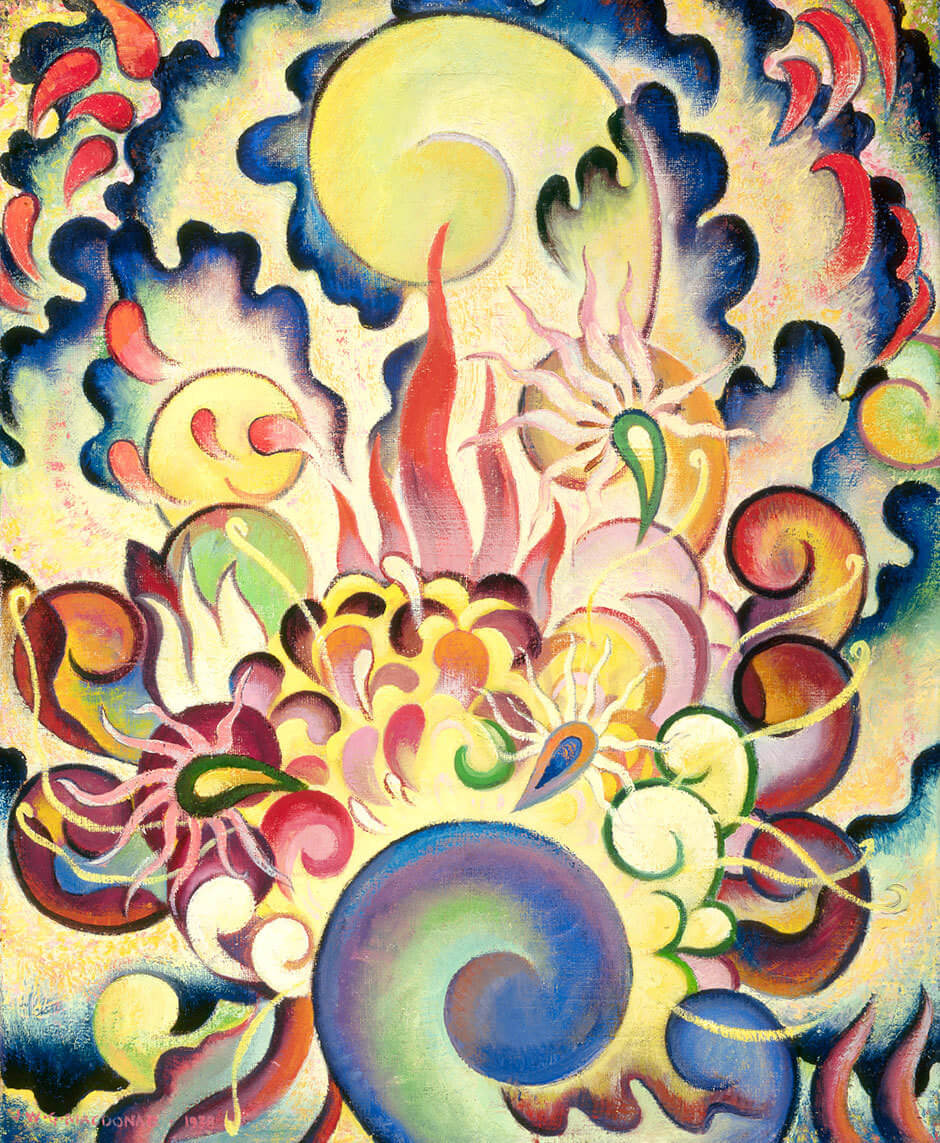

In 1934 Macdonald painted his first semi-abstract painting Formative Colour Activity. Though it would be two years before he resumed his experiments, this work marks the beginning of the artist’s search to express the underlying principles of nature abstractly.

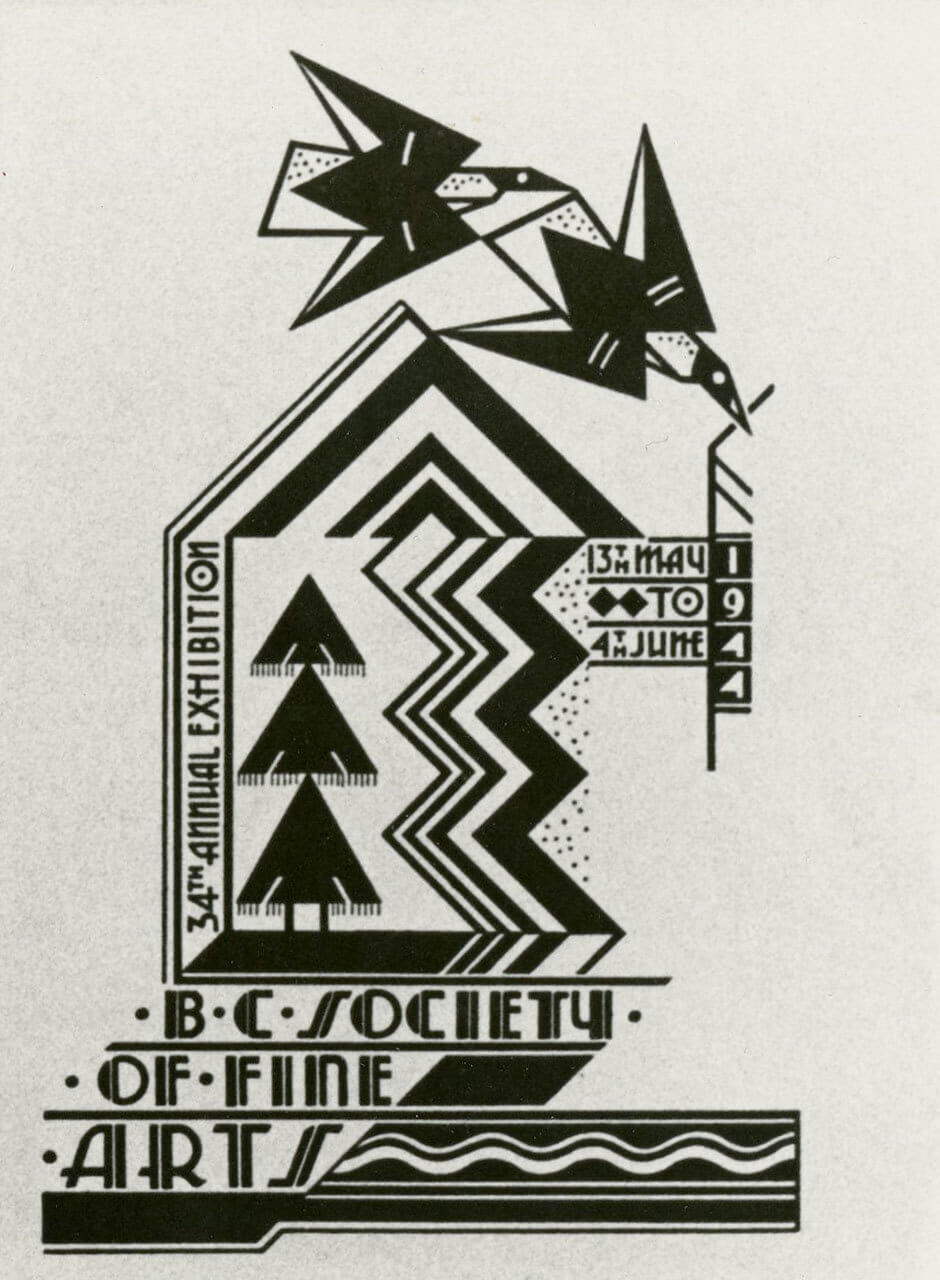

In 1936 he returned to abstraction in the series of works he called his modalities. Though he had kept these abstract experiments secret from all but a small circle of supportive artists, in 1938 he submitted four of them—Day Break (May Morning), c. 1937, and Rain, Winter, and Chrysanthemum (all 1938)—to the British Columbia Society of Fine Arts show at the Vancouver Art Gallery. They must have shocked many viewers, given that, as late as 1928 in Vancouver, many of the local critics found the modernism of the Group of Seven beyond their comprehension.

Although Toronto had hosted the Société Anonyme’s exhibition in 1927, and Bertram Brooker (1888–1955) had mounted a solo show of his abstract paintings there, most of the critics had been hostile. In Quebec, Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960) did not exhibit his first automatiste paintings until 1942. Macdonald, the first B.C. artist to exhibit abstract painting, was therefore surprised at the relatively positive response to his four modalities. In July 1938 he sent his semi-abstract painting Pilgrimage, 1937, to the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, along with the more representational Drying Herring Roe, 1938, for the Century of Canadian Art exhibition at the Tate Gallery in London. In 1939 Rain, 1938, and Flight, 1939, were included in the Canadian Group of Painters exhibition at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario), and Winter, 1938, was selected for the exhibition of Canadian art at the New York World’s Fair.

In 1941 the Vancouver Art Gallery mounted Macdonald’s first solo exhibition. Five years later it gave him another solo exhibition featuring his most recent exploration of abstraction—the automatic paintings that had become the focus of his work since he began to explore automatism under the tutelage of Grace Pailthorpe (1883–1971) and Reuben Mednikoff (1906–1972). In 1947 the San Francisco Museum of Art (now the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) arranged a solo show featuring most of these works, which then travelled to Hart House at the University of Toronto, fortuitously coinciding with Macdonald’s move to teach in Toronto at the Ontario College of Art.

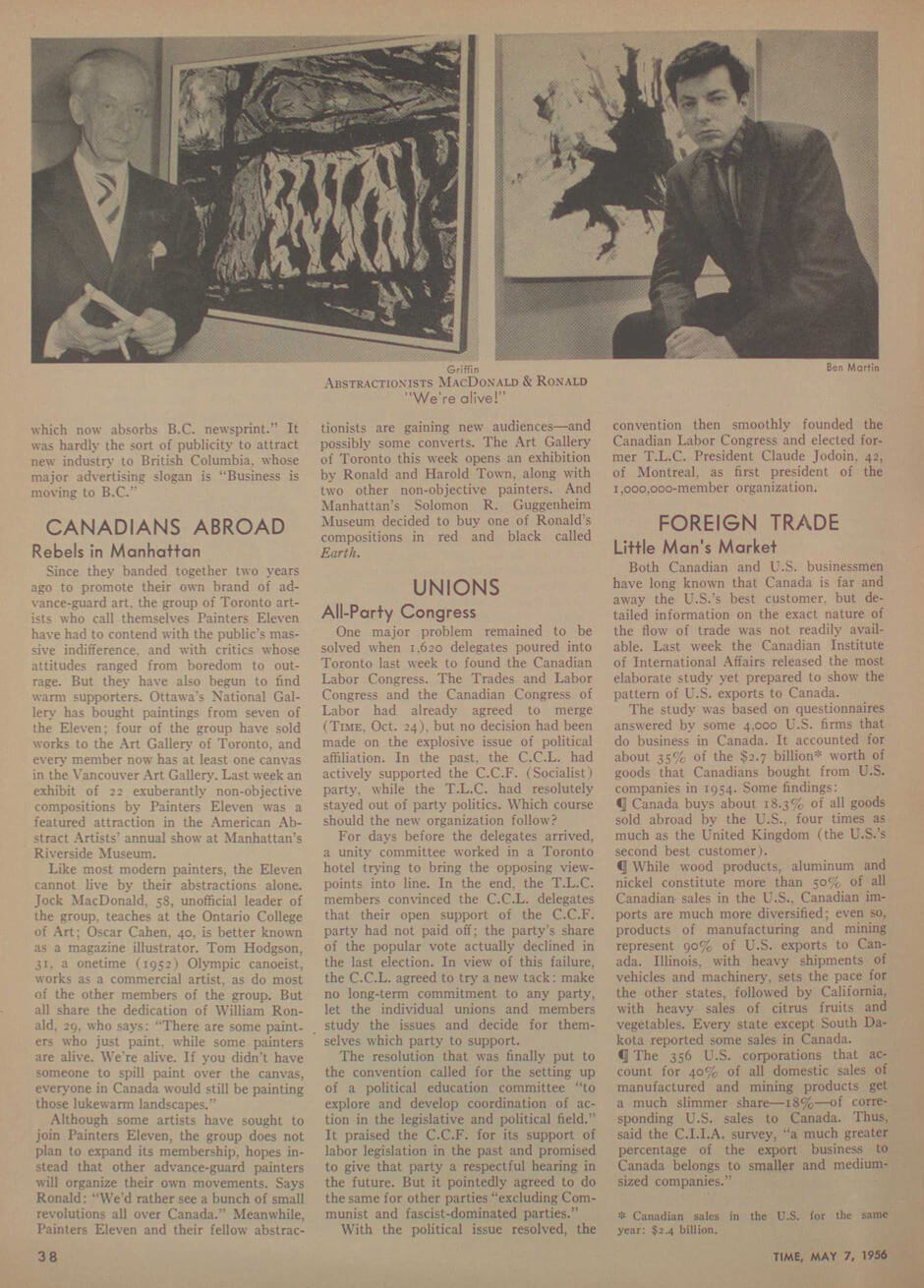

In Toronto, Macdonald championed abstract art in his teaching and played a key role in the opening of the art scene to non-objective art. Several of his former students would become leaders in the fight to gain recognition for abstraction. In 1952 Alexandra Luke (1901–1967), who had studied automatic painting with Macdonald in Banff, organized the Canadian Abstract Exhibition, the first national exhibition dedicated to Canadian abstract painting, and asked Macdonald to lecture on abstraction at the opening of the exhibition. When Painters Eleven was invited to exhibit with the Twentieth Annual Exhibition of American Abstract Artists at the Riverside Museum in New York in April 1956, the American critics generally praised their work, and Macdonald’s Twilight Forms, 1955, was reproduced in Time magazine. (The article identified Macdonald as the unofficial leader of the group.)

Yet Macdonald felt that this success was all but ignored at home, where the work of Quebec abstract artists was championed and much better known. He complained that when the art historian and curator Jean-René Ostiguy (1925–2016) lectured at the Riverside Museum, he “spoke about nothing other than the French Canadian abstract artists … right in the room where Painters XI’s work was exhibited.” In an effort to set the record straight, Macdonald wrote to Maxwell Bates (1906–1980) to explain that his own explorations of abstraction predated those of Borduas, though he gave credit to Bertram Brooker and Lawren Harris (1885–1970) as the “first in the field.”

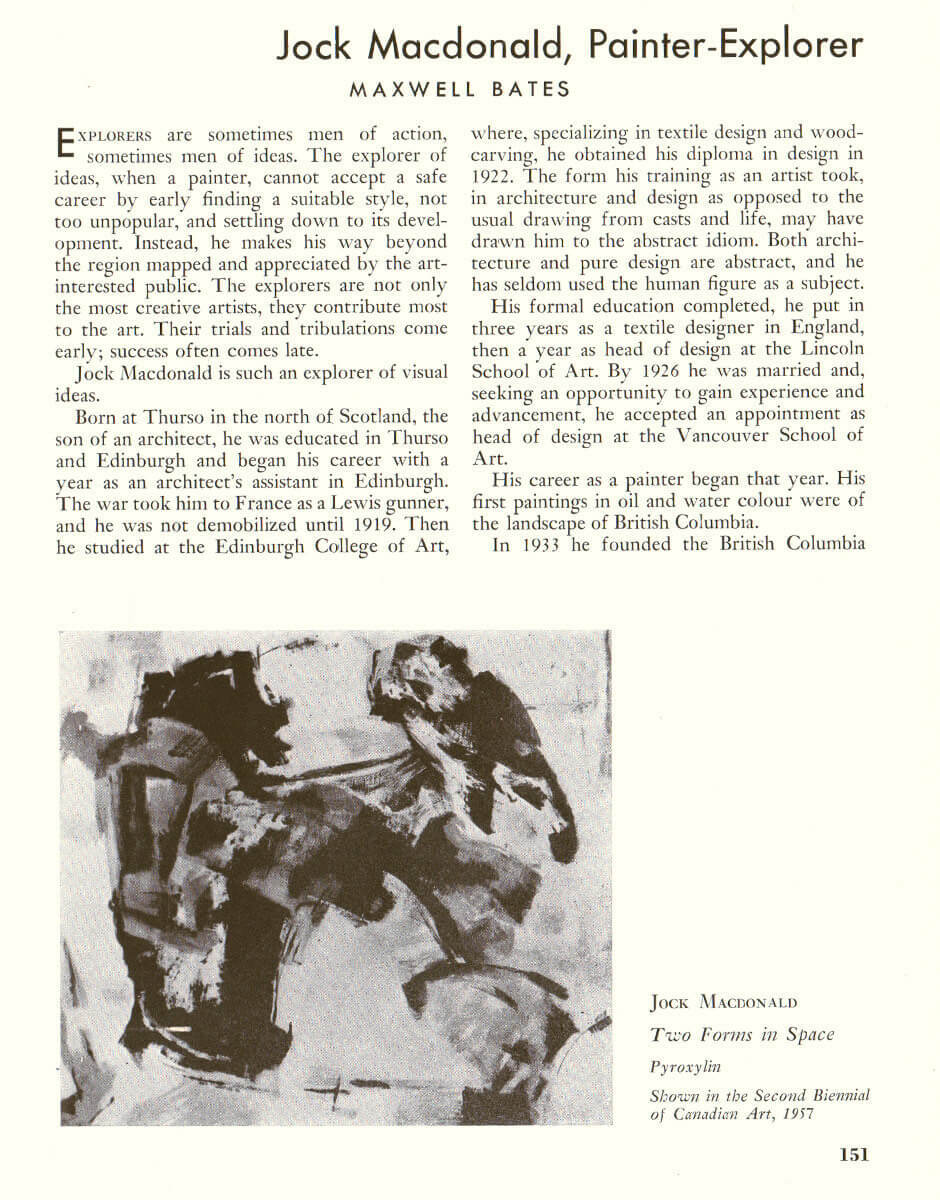

By the end of the 1950s the situation in Toronto and in English Canada more generally had changed, and non-objective art had begun to take hold. As Quebec critic Rodolphe de Repentigny wrote on the occasion of the 1958 exhibition of Painters Eleven in Montreal, “scarcely three or four years [after their first exhibition] they were already considered [established] painters.” In 1957 Macdonald’s significance was confirmed when Canadian Art published “Jock Macdonald: Painter-Explorer” by Maxwell Bates.

Macdonald’s paintings in oil and Lucite were widely recognized for their unique vision and mastery. He was most productive in his last few years when, having found his voice, he worked steadily to create paintings to meet the demands for solo exhibitions in Toronto—at Hart House in 1957, the Park Gallery in 1958, the Arts & Letters Club in 1959, and the Here and Now Gallery in 1960. Macdonald was thrilled when the Art Gallery of Toronto (now Art Gallery of Ontario) offered him a retrospective exhibition in 1960. He wrote to Bates, “The critics spoke very highly of my work, the artists have been quite appreciative and the public thoroughly interested.”

Builder of Art Communities

When Macdonald arrived in Vancouver in 1926, there were few artists’ organizations in Western Canada. Recognizing their value, he participated, often as a founding member, and accepted leadership positions with several of them. He began exhibiting with the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1931. In 1933 he was one of the twenty-eight founding members of the Canadian Group of Painters, the successor of the Group of Seven—a diverse group of progressive artists dedicated to achieving greater recognition for Canadian artists. He exhibited with them regularly both in Canada and the United States.

As a member of the British Columbia Society of Fine Arts, he was elected vice-president in 1939 and president in 1941. In that role he attended the groundbreaking Kingston Conference, which for the first time brought artists from across Canada together to develop an agenda for the arts in Canada. He became a charter member of the Federation of Canadian Artists, the national organization that carried forward the challenge of working on behalf of artists across the country.

When he moved to Calgary in 1946, Macdonald, frustrated by the lack of opportunity for artists who were exploring contemporary expression, wrote: “There are some creative … younger artists + I am trying to have them form a small group, to lift themselves free from the frustrations they have so long endured from The Alberta Society of Artists.” By April 1947 he had facilitated the formation of an association of “six progressive young artists,” the Calgary Group, to focus on non-figurative painting and organized an exhibition for them at the Vancouver Art Gallery. He also joined the more conservative Southern Section of the Federation of Canadian Artists, with the intention of creating a more progressive agenda, and was elected to the executive. After his move to Toronto, he joined the Ontario Society of Artists and, in 1952, became an executive member. That same year he was elected president of Canadian Society of Painters in Water Colour.

In 1954 Macdonald became a founding member of Painters Eleven. He participated in their exhibitions and promoted their work. During his year in Europe in 1955, he called on art galleries in London and in Paris to familiarize them with the work of his Canadian colleagues and particularly Painters Eleven. After visiting galleries in the United Kingdom and Paris, he wrote that he strongly believed that “in Canada there is more distinctive and imaginative painting to be found than over here.” In the spring of 1958 he was invited to curate a room dedicated to the work of abstract and non-objective artists at the Canadian National Exhibition—a task that still remained a challenge, given the lingering controversy in Toronto over the legitimacy of abstract art.

Teacher and Mentor

Except for his eighteen months at Nootka from 1935 to 1936 and his sojourn in Europe in 1955, Macdonald taught every year after his arrival in Canada in 1926 and often during the summers as well. He was an instructor at the post-secondary level in Vancouver, Calgary, and Toronto; at the junior high and secondary school levels in Vancouver; and in art centres at Banff, Edmonton, and Doon during the summers. As professor of art at the UNESCO International Students’ Seminars, he taught in Breda, the Netherlands, in 1949 and in Pontigny, France, in 1950. He was also involved in education in Victoria, B.C., where he was the artist-in-residence at the Art Centre of Greater Victoria (now the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria) in 1952.

Macdonald’s letters to friends and colleagues recount his ongoing frustration with the stultifying and restrictive conditions in which he often worked. They describe his battles with administrators and teaching colleagues who, in their commitment to representational art, were hostile to Macdonald for promoting contemporary art and expression. Macdonald tried to revise the traditional curriculum, sometimes successfully, and sometimes working outside the system to accomplish his goals. Describing his early months at the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art in Calgary as “one big fight,” he succeeded in revising the curriculum to include “all the creative + experimental work I can push into [the students].”

On his arrival at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto, he introduced a course “relating to 20th century creative expressions.” It was not only recognized but accepted as “absolutely necessary”—a major accomplishment, he noted, given that “to have the college recognizing value in any type of expression other than Academic is really something.” In a second-year composition class, students worked “purely on expressive + and creative ideas—with music, with any medium they desire, and all emphasis on space, motion, etc.” Subsequent administrators and colleagues were often less receptive to his initiatives. If administrators were recalcitrant, however, the students were not. Many of them described the pleasure of working with Macdonald not only in class but informally at the college and in off-campus classes and discussions.

Macdonald was an inspirational teacher who supported his students and their work. He introduced Alexandra Luke (1901–1967) to automatic painting at the Banff School of Fine Arts, where he urged students to create from within, with no relation to natural forms. Calgary artist Marion Nicoll (1909–1985) attributed her success as an abstract artist to the influence of Macdonald’s instruction in automatic painting. Thelma Van Alstyne (1913–2008), who studied with Macdonald at the Doon School, described him as a philosopher and mentor, a “superior teacher,” and the “‘father’ of non-objective art in Canada.” William Ronald (1926–1998), later a colleague in Painters Eleven, recalled that the most stimulating parts of Macdonald’s classes were the discussions—of Search for the Real and Other Essays (1948) by the German-American abstract expressionist Hans Hofmann (1880–1966), for example, or of Tertium Organum: The Third Canon of Thought, A Key to the Enigmas of the World (1922) by the Russian mathematician P.D. Ouspensky (1878–1947). He cited Macdonald as the most important influence in his career: “Jock believed in ‘encouraged,’ and ‘encouraged’ was often all one had to live on.”

Macdonald went far beyond being an inspiring and challenging teacher: he became a spokesperson for those students whose work he believed in. He purchased their work, traded his own paintings with them, and lent them money, despite his own precarious financial situation. He wrote: “Apart from my own efforts in the field of art, my greatest happiness is in the odd favorable opportunities I have to fight for the worthiness I sense in the work of our younger artists.”

Above all, Macdonald supported his students, no matter what path they took. As he wrote to Frank Palmer (1921–1990): “All I want you to do is to keep going … to ignore the remarks that you might hear … and ‘dig that furrow’ in your particular field … true to your inner being, your inner awareness. Your inner depth will flower, it cannot help but do so.”

Macdonald’s approach to children’s art classes, which he taught in both Vancouver and Toronto, was interdisciplinary in nature. In 1943, charged with establishing a children’s art program at the Vancouver Art Gallery, he wrote: “We will hold the classes for twenty weeks + I hope to make them … memorable…. We will … enrich our Saturday morning classes with some symphony music…. I believe a little good music vibrating through the gallery rooms is an added enrichment to the desired atmosphere for art instruction + it does bring at least a suggestion to some children of the unity of the arts. I look forward to the Saturday morning classes with uplifting spirit.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements