Jin-me Yoon’s multimedia approach to artistic practice reflects a collage method that she ascribes to her experience as an immigrant, able to see multiple realities at once. Bringing together photography, video, performance, socially engaged art, and a commitment to formal concerns, Yoon mobilizes various ways of seeing and making in individual artworks and in her oeuvre at large in order to layer many points of view, histories, and temporalities.

Photography and Representation

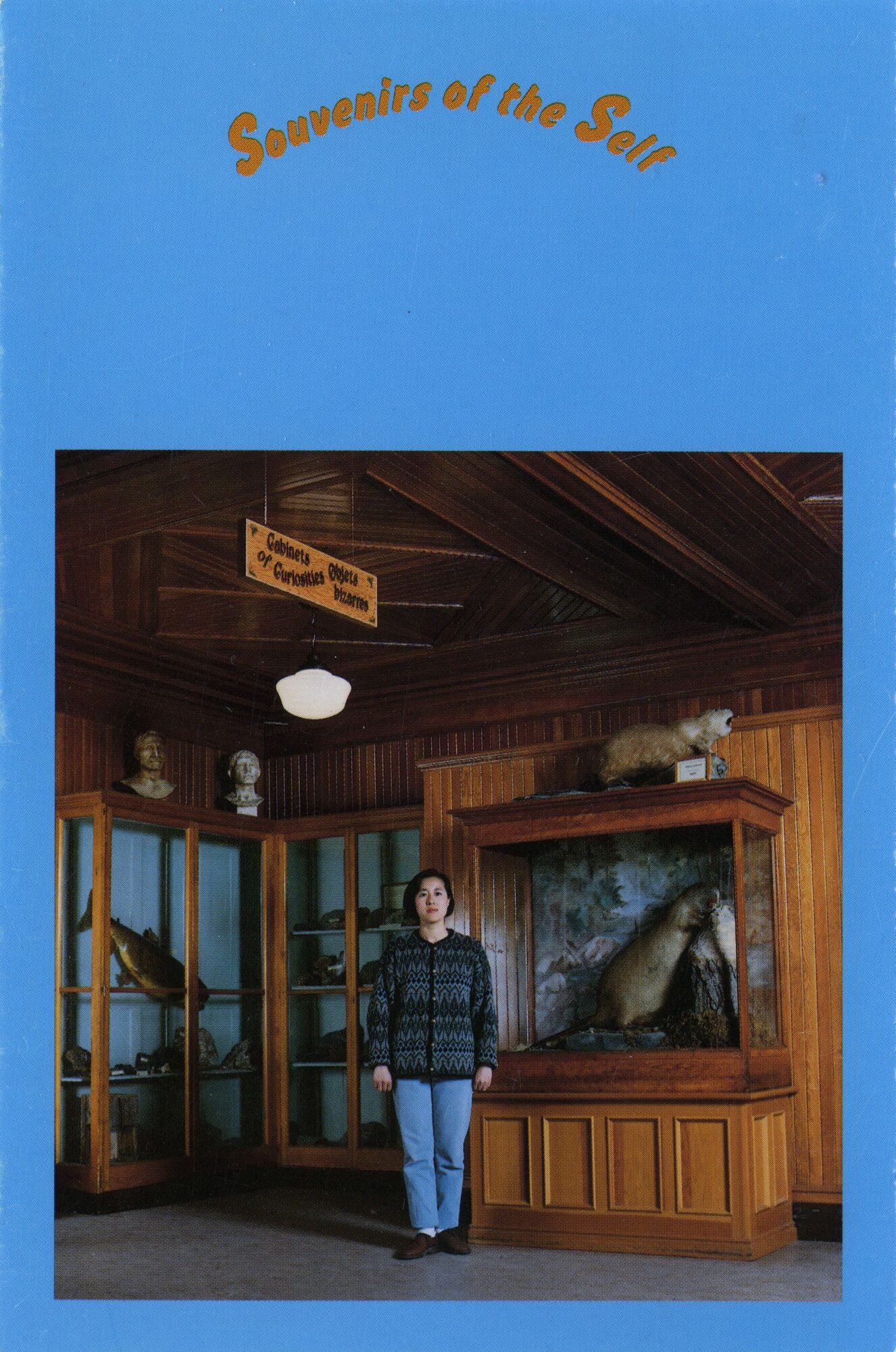

More than just a medium for Yoon, the apparatus of photography and the history of representation are an important theme in her oeuvre. As an artist who trained in Vancouver during the international rise of Vancouver photo-conceptualism, Yoon created early work that is highly theoretical and self-reflexive, while being politically engaged—Souvenirs of the Self, 1991, and A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996, reference the history and function of photography in fields such as tourism, ethnography, and travel documents, as well as addressing art history. In addition, she considers the politics of representation, asking who is represented, how, and why. This conceptual approach reveals her critical training in the humanities and her studies with Ian Wallace (b.1943) at Emily Carr College of Art (now Emily Carr University of Art + Design), as well as the important place of Vancouver photo-conceptualism in Yoon’s art at the beginning of her career. Souvenirs of the Self bears hallmarks of Vancouver photo-conceptualism: the photograph as constructed representation, the appropriation of the postcard format as a mode of advertising for the tourist industry (analogous to photo-conceptualism’s use of the light box, another advertising tool), and the art historical reference to a landscape painting by Lawren S. Harris (1885–1970) in Souvenirs of the Self (Lake Louise).

As artist and critic Leah Modigliani points out, however, “no woman artist has consistently been acknowledged as belonging to the [Vancouver School photo-conceptualists].” Modigliani argues that the marginalization of women artists such as Ingrid Baxter (b.1938) and Marian Penner Bancroft (b.1947) (also one of Yoon’s professors) by the masculinist discourses of Jeff Wall (b.1946) and Ian Wallace is not just an omission, but the result of discursive practices that were theoretically dependent upon the exclusion of women as “oppositional to the mission of a self-selective male group.” Along with Penner Bancroft and others, Yoon developed a feminist response to Wall and Wallace’s stated “counter-tradition,” critically inserting the gendered and, in Yoon’s case, racialized body into the frame and behind the camera, challenging the avant-garde claims of Vancouver photo-conceptualism.

Taking the photo-conceptualist concern with systems of representation (explored in works such as Picture for Women, 1979, by Jeff Wall) and the use of performance in photography as a starting point, Yoon analyzes the ways in which settler-colonial narratives of terra nullius, the fiction that Canada was built on empty land, were created and disseminated through landscape painting, museums, monuments, and the tourist industry. Her work was equally concerned with formal, technical, and conceptual issues. For example, in Souvenirs of the Self, Yoon uses a long lens and shallow depth of field in order to give the impression of her body having been flattened and collaged into the landscape at Lake Louise, questioning the terms of inclusion into Canada’s national narratives by emphasizing her own artificiality. Similarly, the first postcard from the series shows Yoon at the Banff Park Museum, and stages a critique of museums and photography as mediums of national representation, as James Luna (1950–2018)—a long-time friend of Yoon’s—did in Artifact Piece, 1987/90, in which he lay unmoving for hours in a museum display case.

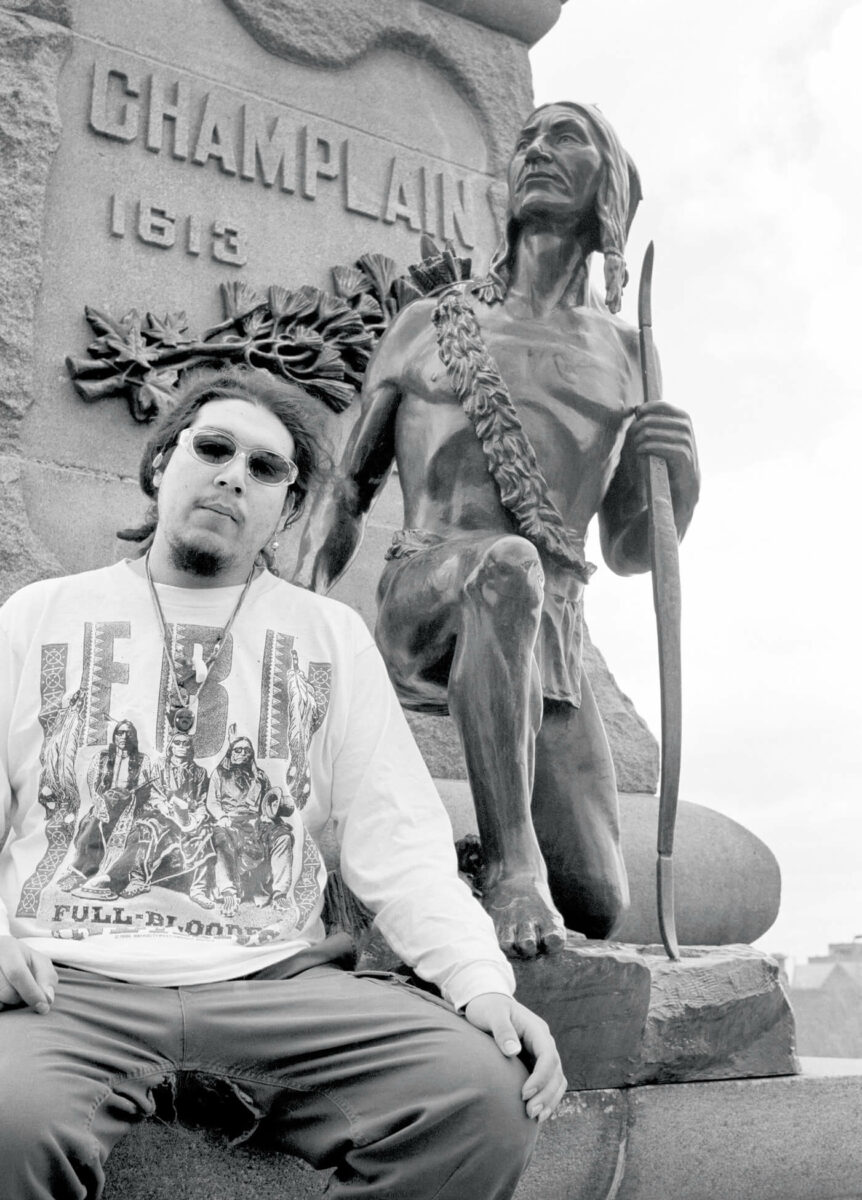

Similarly, the diptych in Touring Home From Away, 1998, showing Yoon and her son looking up at a First World War monument, points to the exclusionary narratives nations use to memorialize national histories. Like The Bear Portraits: 1996 F.B.I. Samuel de Champlain Monument #1, Ottawa, Ontario, 1996, by Jeff Thomas (b.1956), which critiques the portrayal of Indigenous people as anonymous guides at the base of the Champlain Monument on Parliament Hill by re-framing them as the main focus of Thomas’s portrait of his son Bear, Yoon’s photographs challenge the narratives memorialized in monuments, asking whose history is being remembered, and from what perspective. Taking on the tourist industry, Yoon charts a unique course, thinking through national representations that shape public perceptions in everyday life.

In her Intersection series, 1996–2001, Yoon breaks with Vancouver photo-conceptualism to launch an explicit feminist critique of it. This body of work takes aim at the movement’s high production values, visual mastery of detail, and claims to high-art status through citations of history painting by providing a counternarrative that balances these intellectualized claims with assertions of her own gendered and racialized body. She engages with Jeff Wall’s 1984 Milk, which is a paradigmatic photo-conceptualist construction of “defeatured landscapes” that evoke alienation within the Capitalist system. Yoon’s Intersection 3, 2001, playfully challenges the masculinist ethos of Vancouver photo-conceptualism embodied in Wall’s Milk: in her photograph, milk explodes from her mouth as she holds a remote control for a slide projector or camera cable release.

Her action in Intersection 3 references a history of art that has excluded women and people of colour, except as artists’ models: in this scene, she takes charge of the photographic apparatus to control the conditions of her own representation, recalling similar gestures by Tseng Kwong Chi (1950–1990) and Cindy Sherman (b.1954). Yoon’s presence as a gendered and racialized artist professes the possibility of mind and body, of creative production and biological reproduction. After completing the Intersection series in 2001, Yoon has approached her relationship to Vancouver photo-conceptualism lightly, continuing to employ the photographic apparatus in a theoretically rigorous practice, yet exploring new avenues opened up through video, performance, and social practice.

Experiments with Video

For Yoon, the medium of video carries different histories and possibilities than photography. In contrast to photography, which Yoon honed in the context of art school and the rise of Vancouver photo-conceptualism (with its emphasis on creating cinematic effects and desire to join the canons of art history), video was a more experimental medium that arose out of artist-run-centre culture. This activist context amplified certain qualities of video—spontaneity, ease of use, embeddedness in community, and duration. In projects such as between departure and arrival, 1997, Yoon used the medium to reflect on questions of interior experience and history, rather than the external constructions of identity and nation that dominated her early photographic work, such as Souvenirs of the Self, 1991.

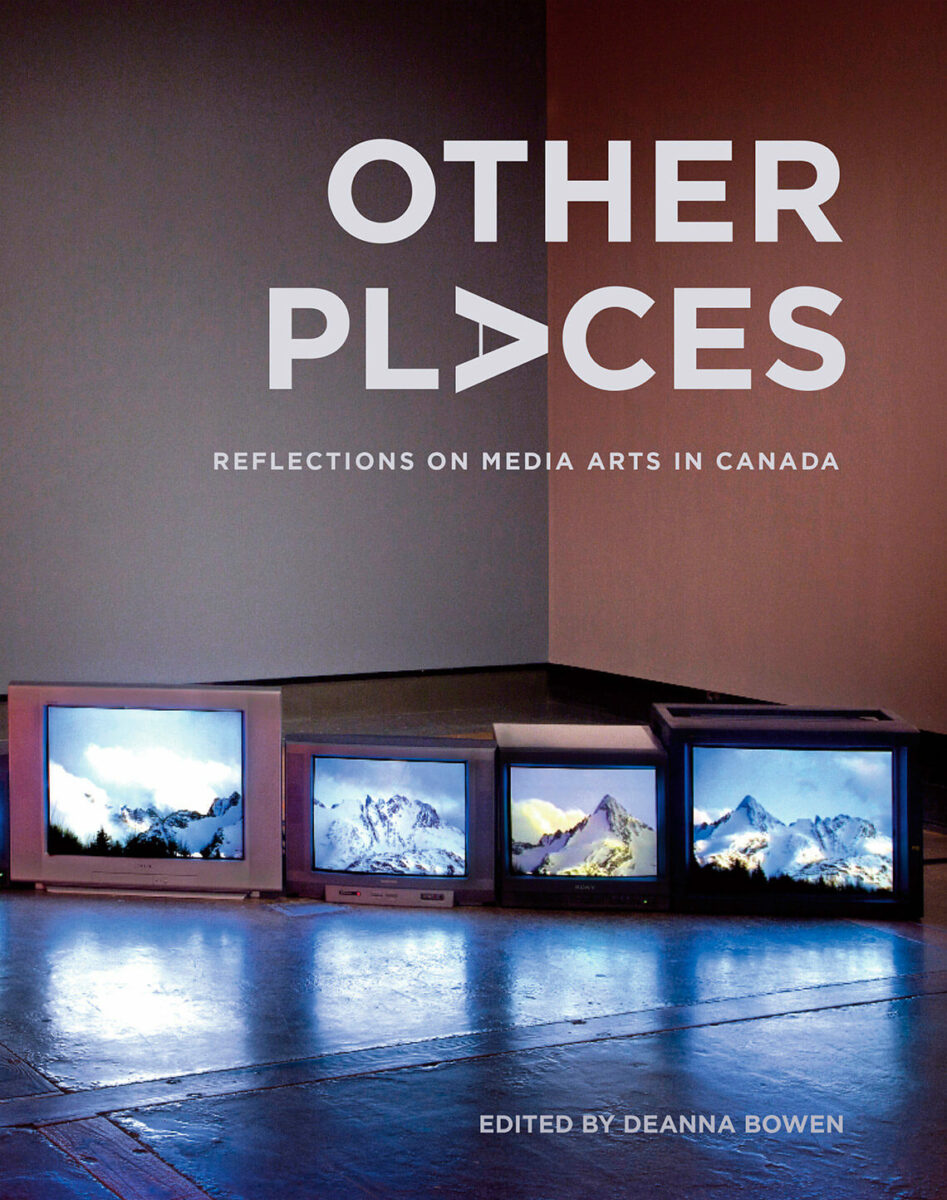

Yoon saw experimental films in Vancouver at the Cinematheque and the Ridge Theatre, and artist videos at artist-run centres such as the Western Front and Video In. At Emily Carr College of Art (now Emily Carr University of Art + Design), Professor Sara Diamond introduced students to video art and its political dimensions, particularly women’s labour history, feminist, and queer video. Yoon drew inspiration from what artist Deanna Bowen (b.1969) identifies as an “alternate set of discourses, practices, and views across the field,” addressing a “broad spectrum of intersectional identity-based issues.” The history of these practices is just beginning to be written; Bowen’s Other Places: Reflections on Media Arts in Canada (2019) pinpoints the critical importance of media arts in opening up a space for Black, Indigenous, disabled, Queer, and visible minority artists.

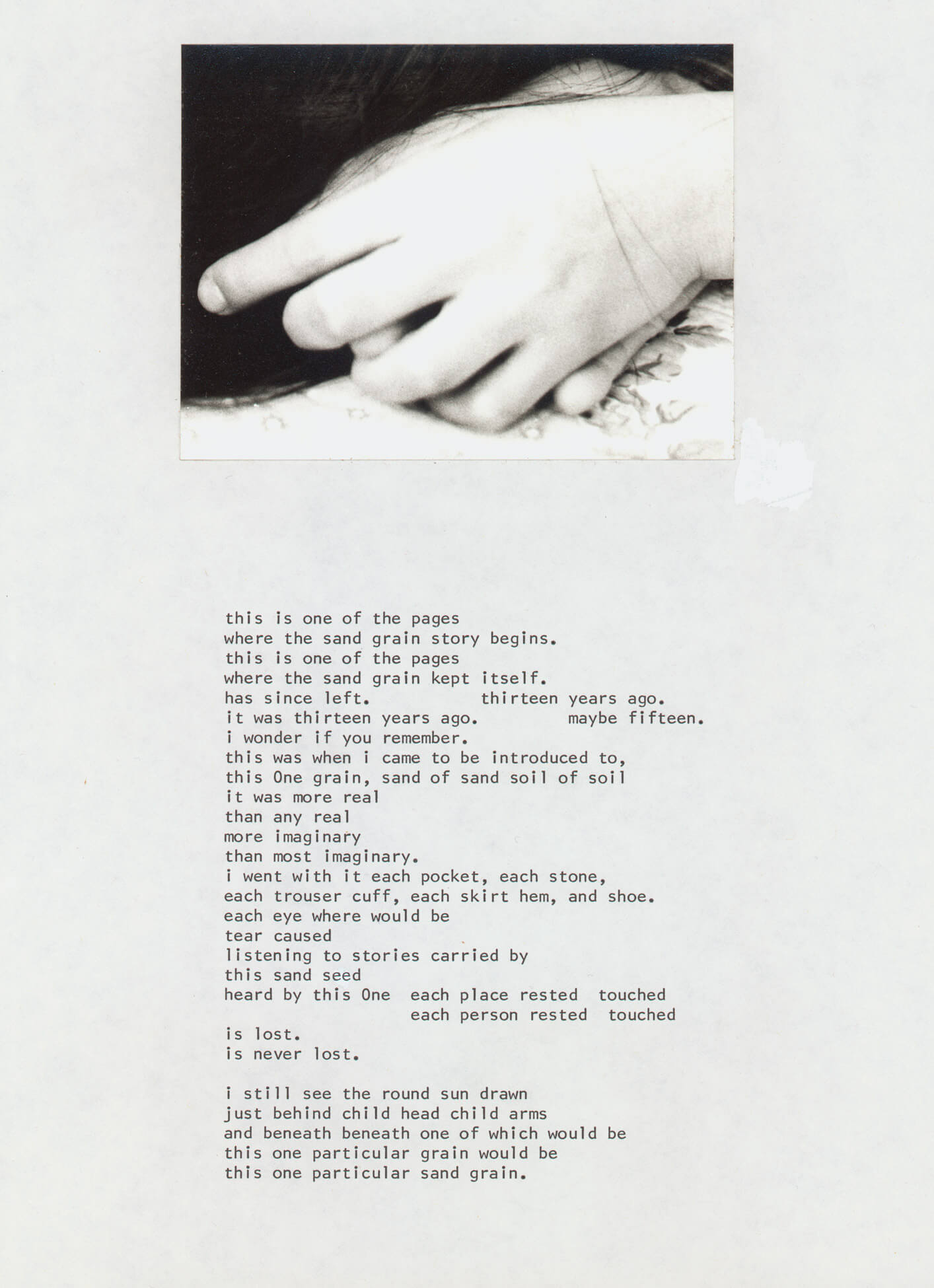

In this context, Yoon began to investigate video’s capacity for duration, which opened up the possibility of exploring interiorized experience rather than exteriorized representation. In Yoon’s hands, this led to projects that reflect upon both interiority and history. Inspired by Lisa Steele’s (b.1947) Birthday Suit: with scars and defects, 1974, and the ways in which Steele visualized her own flesh as an embodied site of memory, Yoon explored the conditions of her own migratory existence in between departure and arrival. Judy Radul contends that Yoon’s use of video in this installation manifests videographic “consciousness,” which pierces through the surface of the identities that Yoon analyzed in her early photographic work. As Radul points out, quoting Bill Viola, “duration is the medium that makes thought possible, therefore duration is to consciousness as light is to the eye.”

In other video works, Yoon mobilizes duration to make visible what she calls “vertical time,” connecting past and present by revealing the palimpsests of history on a particular site or in particular bodies. Arguing that uncomplicated linear narratives sanitize colonialism by focusing on progress and the future at the expense of the past, Yoon reminds audiences that the past resurfaces in ghostly hauntings. In particular, Yoon uses video montage and cinema techniques in works such as As It Is Becoming (Seoul), 2008, Long View, 2017, and Living Time, 2019, to exhume difficult pasts and bring attention to histories of militarism and colonialism lurking just under the surface of our everyday lives.

Untunnelling Vision, 2020, and the works that follow it represent a new phase in Yoon’s experimental camera techniques and video editing, drawing on the legacies of filmmakers such as Maya Deren (1917–1961), who uses denaturalizing effects and filmic collage in Meshes of the Afternoon, 1943, to shift between planes of experience and consciousness (Deren was known for her experimental work in the United States in the 1940s and 1950s). Yoon employs a 360-degree video camera to create images that appear as if they were turned inside out, by processing them as a single view that splays out the entire image across the frame. The pulsating, undulating representations of nature that she creates in this way evoke new intimacies as well as nature’s power, not unlike the video in Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist’s (b.1962) Mercy Garden Retour Skin, 2014. In contrast with Rist’s Edenic images, however, Yoon’s Untunnelling Vision throbs with botanical energy that carries an environmental urgency.

In some passages, footage is rendered in fast forward, referring to the acceleration of time within a model of progress that consumes, builds, and transforms at any cost, without consideration of geological, historical, or ecological time. This effect is enhanced through camera work—shaking, and rapid, choppy edits that cut through linear time, again expressing the multi-dimensionality of time, the past coexisting with the present and the future. As in her early works, which foreground the conditions of image-making in photography, in her most recent projects Yoon highlights the malleable temporality of video to reconnect repressed pasts and damaged presents in the hopes of building better futures.

Performance and the Camera

Yoon’s oeuvre begins out of a performative photographic practice that engages with questions of racialization and the construction of national narratives in Canada through projects such as Souvenirs of the Self, 1991, and A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996. In these works, she places racialized figures—herself, family, or community members—against sites of national articulation such as a museum display case, iconic Canadian landscape paintings, or popular tourist vistas such as Lake Louise. By performing the portrait event with deliberate artificiality, Yoon creates images that provoke viewers to confront their own assumptions about which bodies belong in these constructed landscapes, questioning their own relationship to the land, and revealing that national narratives and projections of racialized belonging are also constructions.

These works belong to a larger tendency in identity-based art of the late 1980s and 1990s, which includes artists such as Cindy Sherman, James Luna, and Ingrid Pollard (b.1953). Although Yoon was not aware of Tseng Kwong Chi’s East Meets West series, 1979–89, the two artists share much in common, in terms of staging racialization in public spaces that are assumed to be “multicultural.” In a Canadian context, Yoon gained prominence for this work, which has an important place in a history of performative photography that uses the artist’s body to critique structures of national representation.

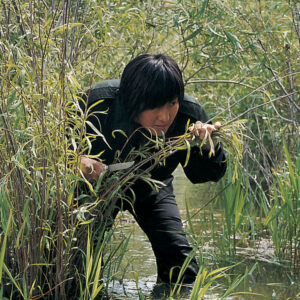

In 2006, with a residency at Ssamzie Space in Seoul, Yoon began a series of performances that used the abject body, crawling along the ground, to challenge Korea’s rapid economic progress and repression of its war histories. Beginning with the laboured movements of The dreaming collective knows no history (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul), 2006, Yoon used the medium of performance not just as a technique of defamiliarization, but as an embodied exploration of the question of progress in the face of colonialism. Impressed by the verticality (both physical and economic) of the city after not having visited in many years, Yoon asks, “What does it take for a nation to rise to such heights? … What does the exhausted body of hyper-capitalism look like?” With increasingly grotesque costumes, as can be seen in Ear to Ground, 2012, for instance, this series of performances enters into dialogue with works by Korean performance artist Lee Bul (b.1964), who explored undercurrents of sexuality and the legacies of militarism through her performances evoking the monstruous body in Cravings, 1988, and Sorry for Suffering—You think I’m a puppy on a picnic?, 1990.

Yoon’s work in the 2020s pushes further into the realm of performance as a social practice, a strategy she initially explored in the community events she planned for A Group of Sixty-Seven. In Untunnelling Vision, 2020, she enacted a space of care and healing encompassing subjective and political positions distinct from her own. Yoon seeks to connect traumatic disjunctures, to open up the possibility of new relational futures through experimental editing and mobilizing what she calls the “synthetic real”—deliberately artificial performances and evocations of traumatic pasts through constructed objects that act as “portals” into the present. She signals the presence of the “synthetic real” by using the Pantone equivalents of traditional Korean Saekdong colours for Rubble the Clown and the painted rocks in All that is carried (Rocks and Rubble), 2020, and for the model of the painted tunnel in Saekdong Skies: Other Ways Through, 2020. These instances of the “synthetic real” create a version of what Alison Landsberg calls “prosthetic memory,” a form of public cultural memory that Yoon employs to enable relational dialogue.

Yoon’s work entails a deep commitment to social engagement. This is a little-known aspect of her art, and yet it underlies the aesthetic techniques she has developed over the course of her career. She defined her practice in the mid-1990s, the early years of socially engaged art, and diverged from the most common forms of social practice and relational aesthetics. In Yoon’s practice, the social engagement is not on display, but sits alongside the final artwork; it is not created for a public, but for a relational group that is a companion to the artwork. Form and aesthetic expression remain paramount.

Yoon’s first foray into this practice was an internet project titled Imagining Communities that she created as a pendant to her one-person show of the same name at Artspeak Gallery in Vancouver (1996). The project was an experiment Yoon designed on the still-nascent internet to create a virtual imagined community that could connect Korean and Korean diasporic women through photographic memories of dispersal and partition. The website displayed photographs from the Korean War to the 1990s that were drawn from personal and public archives and invited public commentary. In the exhibition, these photographs were wrapped in bojagi, or squares of silk, bundling together collective and private memory.

Her best-known early experiment with socially engaged art was A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996. Yoon used the Vancouver Art Gallery “like a community centre,” inviting in racialized immigrants who had not previously been addressed by this “universal” institution. She states,

Our community has never felt welcome in these spaces. An art gallery is just a space to be used, and through its use it accrues value for respective communities traditionally excluded. Pleasure, eating and talking, using this space and getting together is political.

Yoon gathered the group again a few years later to install the work at the Korean Cultural Centre. After the exhibition, each participant was gifted with their own portrait from the wall. She used the occasion to rekindle community ties and open conversations about race and identity in the context of the Los Angeles riots of 1992: to “shift the focus from Korean nationalism to addressing the need to work in coalition with other communities.… Most importantly, what is our relationship to Aboriginal people in contemporary Canadian society?”

Socially engaged art has taken on a greater role in Yoon’s works in the 2020s. Untunnelling Vision, 2020, made relation-making into a form of intra-action in a series of workshops, creating a space of understanding that put racism and settler-colonialism into relation. In the workshop “Relaxing into Relation,” BIPOC community members participated in antiracist decolonial conversations, their neurological perceptions of physical boundaries altered by having just emerged from a sensory deprivation chamber. Neither of these actions was overtly materialized, but rather, they were used to create the social foundations for the final artwork. They both contributed to the aesthetics of care enacted by Untunnelling Vision, and to Yoon’s long-term objectives of building bridges between communities, each with its own traumatic histories.

Abstraction

Yoon uses abstraction to explore the expressive possibilities of lens-based media and its capacity to both represent and embody worlds. In particular, she employs abstraction to shift between multiple ways of being (ontologies) and knowing (epistemologies). She takes inspiration here from the diasporic aesthetic strategies used by Korean American novelist Theresa Hak Kyung Cha in her groundbreaking multilingual book Dictée, 1982, to foreground dislocation and fragmented memory.

From mid-career onwards, Yoon has used abstraction alongside more realist representational modes in order to explore different ways of embodying emotion and different forms of knowledge that are contained in bodies, lands, and environments. Perhaps counterintuitively, Yoon’s use of abstraction increases with the level of research she conducts to create historically grounded and critically engaged narratives, enabling her to embrace both the discursive field and a poetics of politics, as in the work Untunnelling Vision, 2020.

Abstraction emerges as a companion strategy to representation in The dreaming collective knows no history (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul), 2006, where she crawled between the Japanese and the American embassies in Seoul, pivoting her point of view from a vertical to a horizontal axis in a manner that allowed her to disrupt the disciplinary and logical orders in which she was trained.

This is particularly visible in As It Is Becoming (Seoul), 2008, where her black-clad body moves through the city, head-down, abstracting her human form. In the installation, she places monitors on the ground, drawing upon minimalist and conceptual strategies of the 1960s and 1970s, and inverts the image of the city, freeing the artwork from Western spatio-temporal constructs and the modern obsession with progress and rationality. This enables the exploration of other orders and senses—duration, body, and sound. The result is a dredging of the subconscious of history, an airing of forgotten spaces and repressed memories. No longer focusing solely on the historical and sociological construction of images and perceived realities that exist in the plane of rational thought, Yoon’s work delves into the affective and sub-rational.

In This Time Being, 2013, Yoon abstracts her body further, from black-clad enigma to non-figurative form. In this series of sculptural portraits, Yoon positions a human-scale sheet of flexible black rubber in various sites on Hornby Island. The sculptural portrait series evokes multiple systems of representation—autobiographical (as an abstraction of Yoon’s body), art historical (as a response to minimalism), and material (referring to colonial histories of rubber production and circulation). Its changing meanings and shape resist fixity and reveal the ways in which this body transforms in relation to systems and environments. In this way, This Time Being uses the abstract figure as a mode of simultaneously holding and connecting meanings and ways of knowing, refusing fixed binaries and hierarchies.

With Long View, 2017, Yoon takes these insights about abstraction to her video works, in passages that hover on the edge of narrative between painterly distortions and collaged images. When a figure in black jumps into a hole in the ground, the action sets off a geyser of abstracted forms montaged with flashes of archival images from the Korean War. This sluice opens up a rush of entangled collective and perhaps personal family memories, sufferings, and histories of war that connect multiple ways of knowing—embodied experiences, intergenerational traumas, and recorded histories.

Combining cinematic camera work and experimental editing techniques, Long View, Living Time, Saekdong Seas, 2020, Untunnelling Vision, Dreaming Birds Know No Borders, 2021, and Mul Maeum, 2022, summon up the ways in which the body and the nervous system hold on to intense experiences of trauma, beauty, love, and sorrow, as well as the ways in which we confront the possibility of our own deaths and the deaths of loved ones. The emotional registers that Yoon explores in these abstracted passages exceed and exist alongside the possibilities of photographic and cinematic realism. The result are works that weave together narrative figuration and critique with affect and embodied histories, producing a poetics of reflection and repair that links past, present, and future.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements