Untunnelling Vision 2020

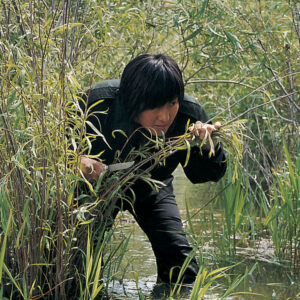

Jin-me Yoon, Untunnelling Vision (video still), 2020

4k and 360˚ single-channel video, 21:26

Jin-me Yoon’s Untunnelling Vision is a multimedia installation, the production of which also included elements of social practice and performance. The main focus of Untunnelling Vision, the video, is structured in three parts, which use different camera techniques to embody multiple conceptions of time, resisting linear settler-colonial narratives of progress, evolution, and development. Complementing the video are site photographs, performance remnants, and the photographic sculpture Saekdong Skies: Other Ways Through, which literally and metaphorically proposes multiple ways through tunnels, a symbol of unbridled development. Untunnelling Vision marks a watershed in Yoon’s oeuvre, in that it explicitly connects past, present, and future, building the groundwork for other conditions and new possibilities.

The video opens on a carousel, where paintings recalling the landscape traditions of Europe spin by. A train passes, then the video cuts to black and white footage of tourists in what appears to be a frontier town—the Heritage Park Historical Village in Calgary, Alberta, Canada’s largest living history museum. The camera follows two figures, Yoon’s son, Hanum Yoon-Henderson, and seth dodginghorse, an Indigenous artist living on the Tsuut’ina Nation, as they walk through the nearly abandoned Heritage Park together. This segment conveys a sense of constructed past-ness through the use of black and white imagery and stuttering, interrupted pacing, giving the impression that the men are visitors from the future, bearing witness to the ways in which colonial narratives are constructed through landscape painting, museums, and tourism.

This first section intercuts between Heritage Park and a tunnel at a nearby site that connects Calgary to Tsuut’ina Nation. Yoon-Henderson and dodginghorse walk through this tunnel under construction, a symbol of speed and progress, blasting straight through the land, “standing in for worldviews that privilege a direct route from point A to point B.” Their steps echo and they begin to play with sound. One throws rocks, another stomps their feet, and they begin to create a musical soundscape.

The second section of the video is set on a piece of the Tsuut’ina Nation’s land that the Canadian armed forces leased for war simulations. Strewn with rubble, it was later used as the set for the Canadian movie Passchendaele, 2008, which tells of a First World War battle that has a symbolic place in the story of Canada’s independence from Britain. This part of the video includes an important scene that reflects the results of three years of relationship-building and workshops between Yoon, Tsuut’ina, and other artists based in Mohkinstsis (Calgary). During these gatherings, open to Indigenous and racialized people, and co-facilitated with the artist’s sister, social justice advocate Jin-Sun Yoon, the group explored inherited histories of colonialism, seeking to think beyond siloed habits of “tunnel vision.” Yoon does not equate different histories and positions, but instead seeks to put them into relation—a theme that she threads through the work with formal strategies, in particular through her use of sound. In this scene, each of the participants improvises an instrument made from detritus found on site. Beginning tentatively, the sound eventually resolves into a composition that is not dominated by one single theme or melody.

The third section of the video builds on the collaborative soundscape of the previous part, with a scene showing participants passing fabricated rocks painted in Korean saekdong colours, witnessed by Korean and Tsuut’ina elders. These passages are intercut with scenes showing the trickster figure Rubble the Clown, who haunts the site with the absurdity of the human presence behind the landscape’s ruin. The segment comes to a close with images of grasses and skies turned inside out, as Yoon flattens 360 degree camera images into two dimensions, as if centring perspectives from earth and sky.

This utopian vision of interrelationality with nature is interrupted at the end of the work, however, when the scene cuts to black and plunges into water, looping the video back to its beginning, with its critique of progress and extractivist modernity. As if waking the viewer from a dream, Yoon brings us back to our current reality, underpinned by a singular narrative of progress. Untunnelling Vision warns of the earth’s ruin, linking it to the devastation of settler-colonialism, the wreckage of Korea that Yoon experienced as a child, and the ongoing damage caused by development at all costs.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements