The Dreaming Collective Knows no History (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul) 2006

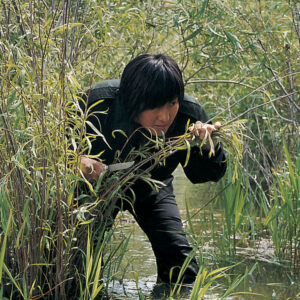

Jin-me Yoon, The dreaming collective knows no history (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul) (video still), 2006

Single-channel video, 18:08

In The dreaming collective knows no history (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul), a video created during a residency at Ssamzie Space in Seoul, Korea, Jin-me Yoon drags herself along the ground between the Japanese and United States embassies in Seoul. The two sites summon up the histories of Japanese colonialism in Korea (1910–45) and American imperialism through the long Cold War that continues to station over 25,000 troops in South Korea. Yoon conjures up these violent histories through her evocation of war-ravaged bodies and physical struggle in her performance, memories that are suppressed in a contemporary Korea focused on the slick and shiny promises of advanced capitalism. Ahead of its time, The dreaming collective knows no history makes a critique of Korea’s breakneck speed of progress and its human toll that has now become a focus of Korean popular culture in films such as Parasite (2019) and the TV series Squid Game (2021).

As Yoon pulls herself along the pavement on a platform, well-dressed businesspeople walk by without making eye contact or stare from a safe distance, as if embarrassed by her presence and worried about contagion. The experience for the viewer is not as easily distanced, as the video’s sound insists on being noticed. We hear the scraping vibrations of the wheels, Yoon’s laboured breathing, and the jerking sounds the board makes as she pushes it along the ground. Physical effort, friction, and difficulty come into focus as we watch Yoon’s painful progress from a symbolic site of colonial oppression (the Japanese embassy) to one of contemporary subjugation and complicity (the American embassy), the toll on her body evident with every movement. The work launched a series of mid-career projects that create alternative paradigms of thought, experience, and representation beyond the future-focused historical amnesia of postwar modernity.

With The dreaming collective knows no history, Yoon revolted against the onwards and upwards velocity of economic progress that surrounded her and pivoted her black-clad body from a vertical axis, as seen in Fugitive (Unbidden), 2003–4, to a horizontal one, exploring the urban environment laterally. In some of the works from this period, Yoon disfigured her body with a variety of prosthetic devices, in order to conjure up deeply suppressed memories and ugly political truths. In others, she passed through urban landscapes, her horizontal movements designed to upend modernist, progress-focused visual narratives and to explore undercurrents of contemporary history and society. The topsy-turvy world she elicits is embodied in multiple elements in works such as As It Is Becoming (Seoul), 2008, which incorporates several videos of crawling performances in an installation. With videos on monitors placed on the ground or projections shown upside down, Yoon compels a reorientation of the spectator’s body as they view the work.

Letting go of millennia of evolution that brought humans to their bipedal stance, Yoon assumes a horizontal posture in order to probe humanity’s difficult histories through bodily experience. These lateral crawling works are in dialogue with the endurance art of the 1960s and 1970s, and they are often compared with William Pope.L’s (b.1955) crawls through the streets of New York City in a business suit or a Superman costume. While both artists level their criticism at capitalism, Pope.L’s crawls are a comment on its failure, whereas Yoon’s works address its success. Pope.L sought to bring dignity to people experiencing homelessness and degradation on the streets; Yoon reveals anxieties and war memories that lie just beneath the surface of life in a still-militarized yet newly prosperous Korea.

Ahead of their time, these works lay bare the consequences of the unresolved Cold War in Asia obscured by the economic success of the “Asian Tigers”—South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore. These regional histories of global significance were later taken up by artists such as Koizumi Meiro (b.1976) in Voice of a Dead Hero, 2010, in which the artist, dressed as a Japanese war veteran, crawls through the streets of Tokyo haunting contemporary shoppers, or Ho Tzu Nyen (b.1976) in Hotel Aporia, 2019, which awakens the long-concealed histories of Japanese imperialism in Asia.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements