Long View 2017

Jin-me Yoon, Long View 1, 2017

Chromogenic print, 83.8 x 141 cm

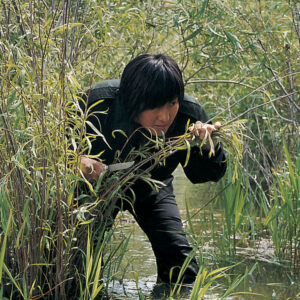

A commission for Landmarks/Repères, a program created for Canada’s sesquicentennial, Long View is a video and photographic work in which Jin-me Yoon explores historical, military, and personal threads that connect geographies across the Pacific Ocean. The work is anchored by a photograph of the artist looking out toward the sea with binoculars, echoing images seen in the media of North and South Korean soldiers mutually surveying each other. She gazes toward Korea from Long Beach in Pacific Rim National Park Reserve, on the traditional territories of the Nuu-chah-nulth Nations (which include the Toquaht and Yuułuʔiłʔath First Nations): both theatres of war during the Second World War and the Cold War, both sites of personal importance to Yoon. Her family joins her on the beach, appearing in the video, creating a hole and then a mound in the sand.

-

Alex Colville, To Prince Edward Island, 1965

Acrylic emulsion on canvas, 61.9 x 92.5 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa -

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Theatre Box (La Loge), 1874

Oil on canvas, 80 x 63.5 cm

The Courtauld Gallery, London -

A North Korean soldier looks toward the South side through a pair of binoculars in between two South Korean soldiers at the demilitarized zone (DMZ) in the Joint Security Area border village of Panmunjom in 2003

Photograph by Vincent Yu/Associated Press

-

Jin-me Yoon, Long View (video still), 2017

Single-channel video, 10:03

With its distinctive binoculars, the photograph echoes modernist tropes of (male) spectatorship such as The Theatre Box, 1874, by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) and Alex Colville’s (1920–2013) perspective on the female gaze, as seen in To Prince Edward Island, 1965. Through the focus placed on the instrument of seeing—the binoculars—Yoon juxtaposes the way that opticality claims space (the photograph) against embodied experiences of land and histories (enacted in the video). Yoon interweaves the there with the here, contrapuntally layering different sites and histories.

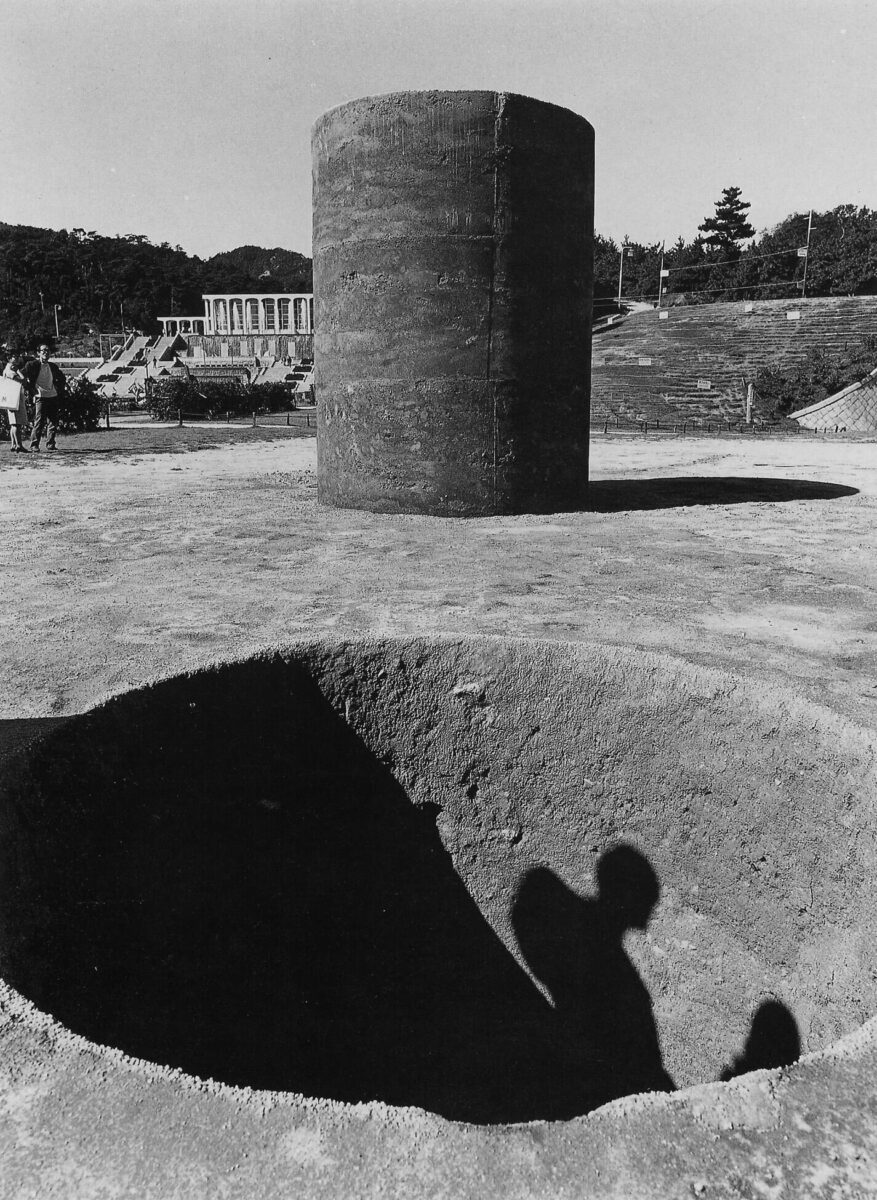

The video begins with Yoon’s parents and children digging a hole on the beach and making a mound next to it. The activity evokes, among many other things, the childhood belief that one could dig a hole through to the other side of the world (and that everything is connected), Korean burial mounds, the passing of generations, and the evanescence of life. This act resonates with a number of artistic “earthworks” from the mid-1960s, such as Hole, 1965, by Group I of Kobe, who for eleven days dug a ten-metre hole and filled it back in, in an act of collective Sisyphean futility; Placid Civic Monument, 1967, created by Claes Oldenburg (1929–2022) and dug by a professional gravedigger in a rectangular shape that referenced the Vietnam War; and Phase—Mother Earth, 1968, by Sekine Nobuo (1942–2019), in which the artist created a perfectly cylindrical hole and a matching protrusion in the landscape, giving the impression of a plug having been removed from the earth temporarily, until the elements returned it to its original phase.

Yoon’s hole straddles the logics of Oldenburg’s and Sekine’s works, both referencing war histories and also presenting phenomena as phenomena: a hole, after all, is what we apprehend directly as a hole, and not an idea as expressed through a hole. As Lee Ufan describes Sekine’s work, it is “not the transformation of an idea into a world of its own, but an event in which the internal and external interact.” Following the digging of the hole and the creation of the mound, Yoon’s video cuts to the mound being eroded by time, dusted with snow, and merging with the ocean. Her intervention, however, has an enduring existence, as the hole also becomes a site of memory in the video. A black-clad figure appears and steps into the hole, releasing a maelstrom of abstractions and montaged images that link Yoon’s two emotional landscapes of Korea and Canada, creating a topsy-turvy world that conjures an oceanic state: a making of worlds that resists the ordered opticality of the gaze.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements