Three mid-twentieth-century contemporary art movements—Quebec automatism (informed by international Surrealism), French Lyrical Abstraction, and American Abstract Expressionism—were influential in the development of Jean Paul Riopelle’s body of work. Although he made every effort to set himself apart from them, it is in relation to these movements that the significance of his art must be understood. In Quebec he was a leading member of the Automatistes, signing Refus global in 1948 before setting his sights on France. Once settled in Paris, he fell in with the Surrealists then joined the Lyrical Abstractionists. Finally, during the 1950s, American critics associated him with the Abstract Expressionists, but he rejected the comparison. The artistic positions taken by the young Riopelle in the first decades of his career connect him to many movements and artistic practices but they are united by a single thread: Riopelle’s intense desire to stand apart from his peers and follow his own path.

Automatism and Its Rejection

Jean Paul Riopelle began his career as a full participant in the Quebec Automatiste movement. He was a contributor to the group’s manifesto Refus global, released on August 9, 1948, insisting that its text not be a repetition of similar European declarations such as the Surrealist movement’s Rupture inaugurale, which he had also signed in 1947 alongside André Breton (1896–1966). Riopelle defended the scandalous Refus global manifesto after its historic publication, and his abstract works at the time were in harmony with the intentions of his fellow Automatistes, including Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960) and Marcel Barbeau (1925–2016). Collectively they called for a rejection of figuration in favour of the spontaneous, instinctive creative act. In Riopelle’s Hochelaga, 1947, for instance, touches of colour are distributed over the entire surface, which is strewn with drips that suggest a speedy execution and a lack of conscious control—hallmarks of the automatist style.

However, by the early 1950s, Riopelle had begun to break away from the movement. In an automatist work of art, the artist maintains control even though he or she might use coincidental elements to create the composition. This bothered Riopelle, who was in search of an art that removed any type of control and allowed for free creation. He found the work of his compatriots, such as Borduas and Barbeau, limited in this regard. They restricted the opportunity for accidental elements to invade the composition of a painting. Riopelle understood this to be a rejection of chance and he distanced himself from them as a result.

For instance, Borduas’ two-stage creation of Nature’s Parachutes (19.47) (Parachutes végétaux [19.47]), 1947, seems to restrict chance. The dark background was painted first; then, once the paint had dried, the “objects” (the “parachutes”) were added and carefully placed to avoid any overlapping. The Montreal artist Guido Molinari (1933–2004) suggested that this composition would have been impossible if Borduas had proceeded with his eyes closed. Yet Borduas claimed to have no preconceptions of what his painting would become: “faced with the white page, my mind free of any literary ideas, I respond to my first impulse. If I feel like placing my charcoal in the middle of the page, or to one side, I do so without question, and then go on from there.” Therefore, his assertion must be questioned. It is difficult to see how any element of the whole could be moved without compromising the balance of the composition. Something similar can be said of Barbeau’s painting, Tumult with a Tense Jaw (Tumulte à la mâchoire crispée), 1946. In this painting the artist oriented his marks in a V shape, its ends pointing to the upper left and right corners of the pictorial surface. It seems that here, too, a “restriction of chance” occurs.

At the Paris exhibition Véhémences confrontées (Confronted Vehemences) at La Dragonne, also known as the Galerie Nina Dausset, which ran from March 8 to 31, 1951, Riopelle joined several other artists in releasing a written statement that outlined their dissenting position against the movement:

Automatism, which was meant to achieve total openness, has shown itself to be limited by the action of chance. The refusal of the conscious act turns it into a systematic “ism.” A painter who draws involuntarily can only repeat indefinitely the same curve; nothing allows us to prefer this act to one restricted by the kind of tool an architect might use to draw a curve. Only total chance is fertile—no longer an exclusive function of the means, it instead can take real control—because truly total chance necessitates a physiological, physical, and psychic opening by the painter’s physicality, giving cosmic liberation every opportunity to enter and influence the work.

Ironically, while Riopelle spoke out against automatism in Paris, his contribution to Véhémences confrontées, Untitled (Sans titre), 1949–50, embodies the movement’s desire for “total chance.” Following the showing of this painting, however, he withdrew from the group altogether, which he felt had betrayed him because they claimed a “total openness” that nonetheless restricted opportunities for true spontaneity to occur.

Ultimately, Riopelle could not accept automatism as a “refusal of conscious intent” and found it to be a principle that resulted only in constraint. “The important thing is intensity,” he observed, and to maintain a “state of purity, of availability before the work.” Anything less would lead to monotonous and repetitive work. A “dead end“ he declared.

From Surrealism to Lyrical Abstraction

During his first trip to France in 1947, Riopelle encountered members of the Surrealist movement and contributed two watercolours to the VIe Exposition internationale du surréalisme (6th international exhibition of Surrealism) held at the Galerie Maeght in Paris and organized by André Breton (1896–1966). The exhibition included Mother Liquors (Eaux-mères), 1947, which had been given its title by none other than Breton. The composition is typical of Riopelle’s automatist style of abstraction; it is dense and hurried, showing little regard for traditional pictorial space and accentuated by fine pen line to evoke simple shapes and patterns.

Fernand Leduc (1916–2014), a fellow member of the Automatistes, criticized Riopelle for participating. He believed that his friend’s work had nothing to do with the esoteric intentions, which Breton had articulated about Surrealism, in particular his hope to bring occultism back to the movement. Leduc observed that Riopelle “seems to have lost his way even in the execution of his work.” Although Breton had asked for the participation of Borduas and the Automatistes in the Surrealist exhibition, Leduc stated, “There’s nothing for us here.” In the end, Riopelle was the only Canadian, out of eighty-seven artists, to exhibit at the Galerie Maeght. He soon returned home to Quebec but would travel back to France at the end of 1948.

Once back in France, Riopelle quickly reconnected with the Surrealists and André Breton. Before long, however, he realized, that the avant-garde no longer revolved around them. Their reputation had been tarnished during the Second World War after their leader, Breton, went into exile in the United States, and one of their main poets, Benjamin Péret (1899–1959), had relocated to Mexico for a time. Some members, like the writer-performer Tristan Tzara (1896–1963), who had faced Nazi persecution, reproached them bitterly for their desertion. Divisions developed within the group as a result, with some claiming to be followers of Breton and others of the Communist Party. Riopelle felt that there was not much to gain from this infighting and began to look elsewhere for like-minded associates. He found the affinity he had had with the Surrealists to be insubstantial, of the intellect only and not with the imagery; the rapport was “not precise enough,” he observed.

Riopelle would soon fall in with the Lyrical Abstractionists, a group of painters with ideas similar to his own. Their work was abstract, but they sought to move beyond the geometric abstraction that dated back to the paintings of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) and was still favoured by disciples of Piet Mondrian (1872–1944). A famous photo from 1953 brings together several members of the movement, who were represented by the gallerist Pierre Loeb, including Maria Helena Vieira da Silva (1908–1992), Jacques Germain (1915–2001), Georges Mathieu (1921–2012), Pierre Loeb (1897–1964), Riopelle, and Zao Wou-ki (1921–2013).

Lyrical Abstraction, as it was named by Mathieu in 1947, was more in the tradition of painting established by Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), “in which a baroque style extends into expressiveness.” The first exhibition of the group had fourteen participants and included Leduc and Riopelle. It took place at the Galerie du Luxembourg under the title L’imaginaire (The Imaginative World). Mathieu was enthusiastic about the “new Canadians” and their automatism, which he admired for its “advantageous submission to the demands of spontaneity, pictorial indiscipline, technical chance, romanticism of the brush, the overflowing of lyricism.” In this vein, Mathieu’s own abstract works, such as Fourth Avenue, 1957, are a kind of free calligraphy within a central image.

Riopelle’s involvement with Lyrical Abstraction proved to be much more valuable to him than his brief time with the Surrealists. His association with the former throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s was a crucial learning period in which he explored a multitude of ways to consider abstract art without relying on the dominant Mondrian-style geometricism or any other prescriptive formula. Riopelle, described by the French art critic Michel Waldberg as an artist “hostile to any formalism, to any ritualization, even those of a modern whose ‘religion’ exists without God,” would soon take artistic flight in his own way and be rewarded with success in both Paris and in New York.

Apart From Abstract Expressionism

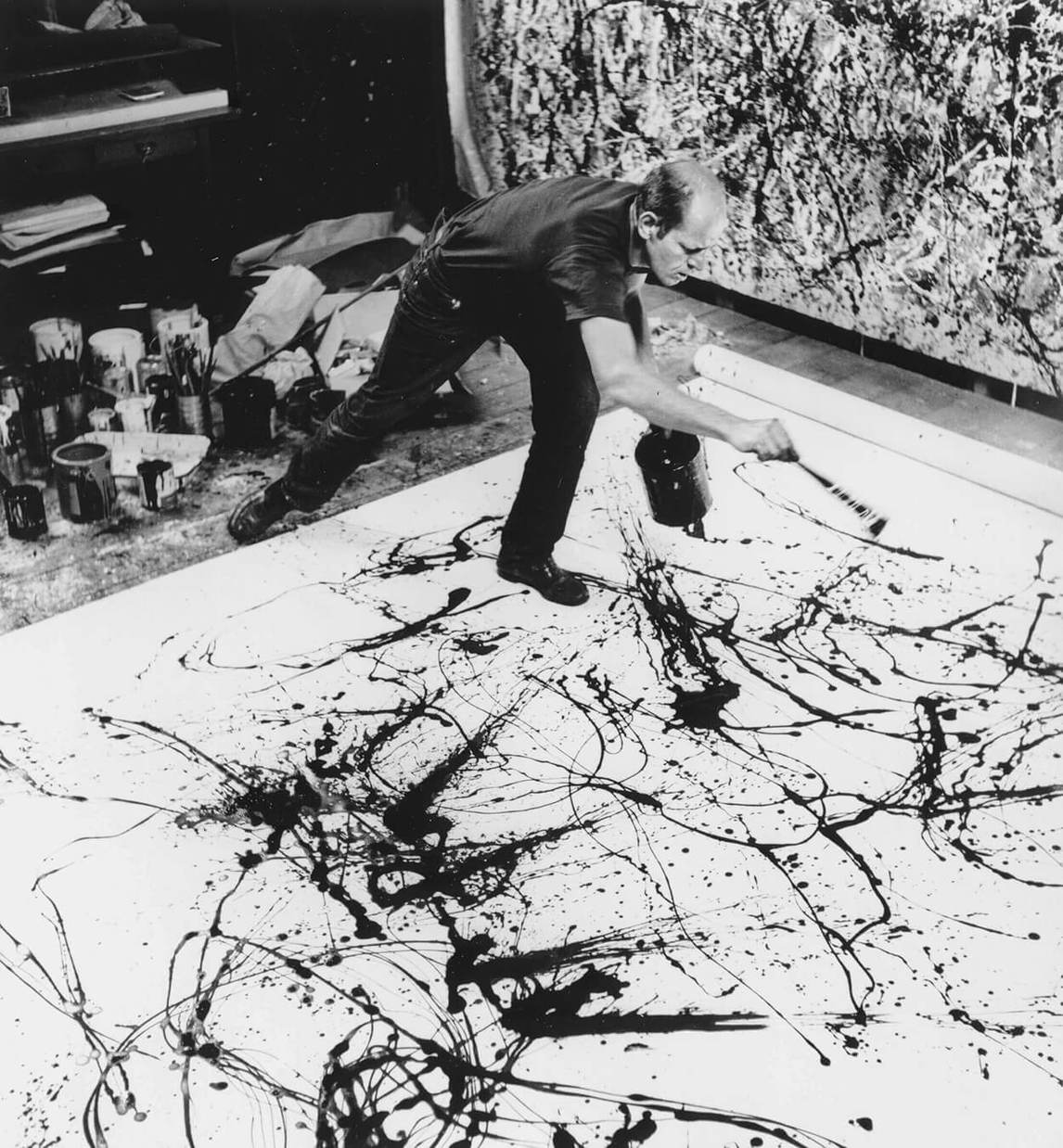

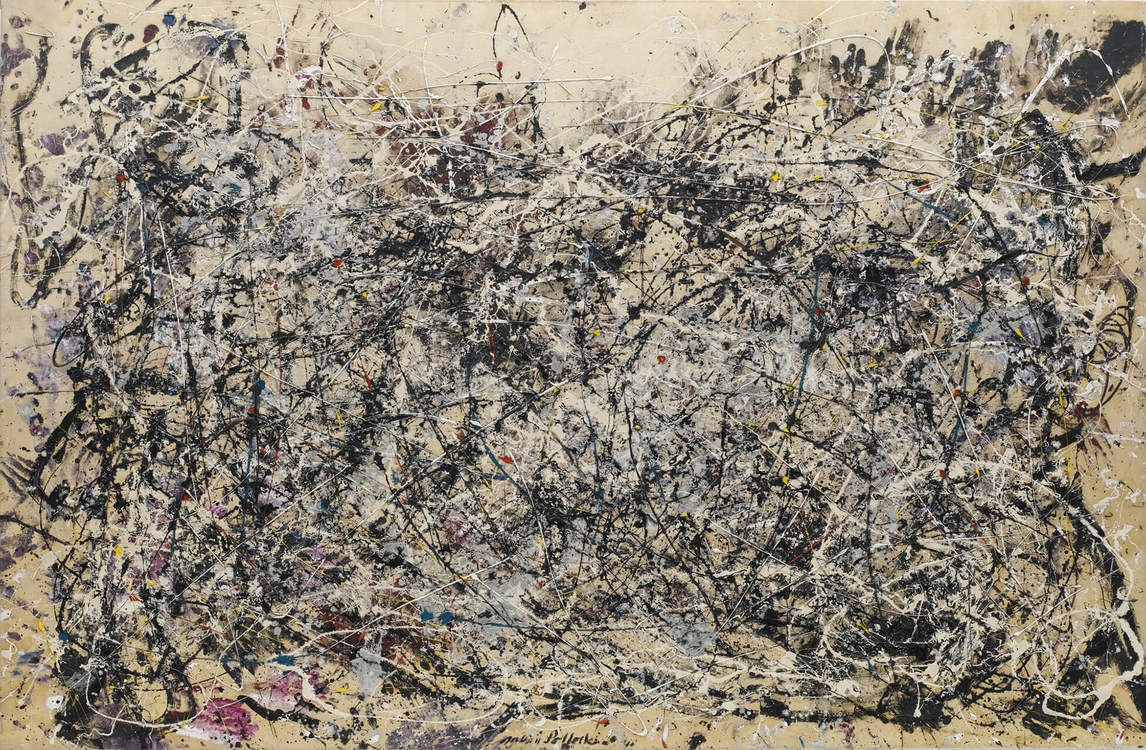

American critics often compared Jean Paul Riopelle—wrongly, in his opinion—to Jackson Pollock (1912–1956). Notably, the art historian Robert Goldwater saw a connection with the drip paintings of the famous American artist in the white paint drips of Riopelle’s Untitled (Stroll) (Sans titre [Promenade]), 1949. One of the first to grasp and describe the important differences between the paintings of Riopelle and Pollock was the art critic Thomas B. Hess, editor of Art News magazine. In his article “Jean Paul Riopelle,” published in the 1973 catalogue of the exhibition devoted to the Canadian painter at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York, Hess noted (without naming Pollock) that certain new American painters, specifically Abstract Expressionists, began with a piece of canvas not yet mounted on a stretcher and either tacked to the wall or simply laid flat on the floor. The paintings therefore developed outward from the centre toward undetermined limits. When the periphery of the image was established, the excess canvas would be cut away, and only at this point would the painting be mounted on a stretcher.

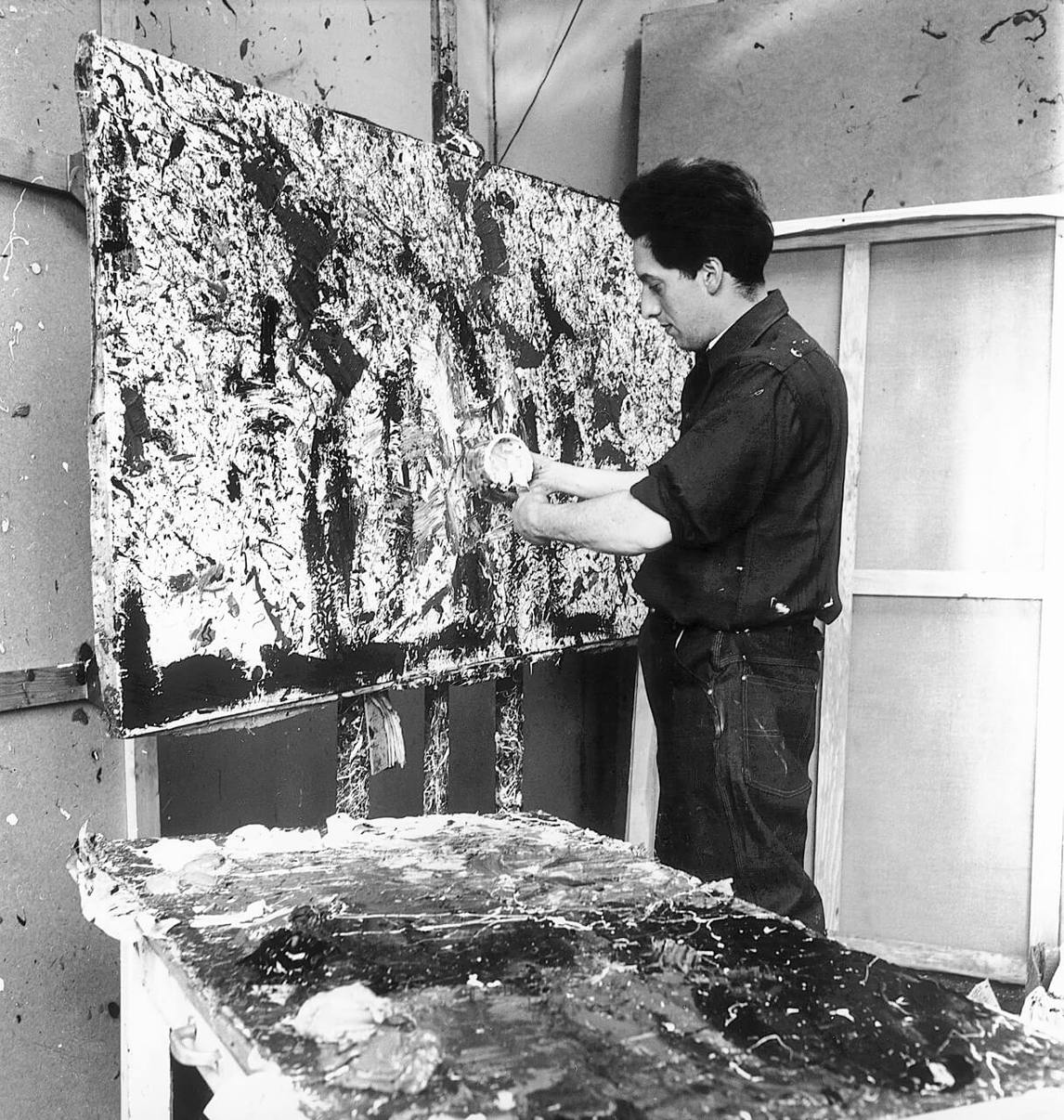

As Hess observed, Riopelle’s process was very different. He always worked with a stretched canvas placed on an easel. He favoured three canvas formats: the portrait (more or less square), the landscape (horizontal rectangle), and the seascape (more elongated to represent a beach or shoreline). Thus, the shape of each composition was decided in advance. In this way, Riopelle was a traditional painter who used formats common to the European painters he most admired: Henri Matisse (1869–1954), Claude Monet (1840–1926), and Gustave Courbet (1819–1877).

Hess’s crucial point was illustrated by including two photos for comparison in his article. One shows Pollock at work in his studio, the other Riopelle in his. In the first image, Pollock is shown creating one of his signature drip paintings. The paint falls on a canvas that has been unrolled and laid on the floor. He dips a dry brush or stick into a can of paint rather than using tube paint. The paint drips from his stick in thin streams or drops. He does not hesitate to step or walk on the canvas. Overlooking the entire picture surface from above, Pollock appears in perfect command of his work, creating an all-over effect without a focal point or a hierarchy. Sometimes Pollock would cut a large painted canvas into segments to make different autonomous works, depending on how the composition had developed as it was created directly on the floor.

In contrast, the second photo shows Riopelle at work. He maintains a much more conventional relationship with the canvas, face to face with his work and maintaining a critical distance from it, as has been traditional among painters for centuries. His canvas, propped up on an easel, shows black patches of paint at the bottom left. These signal the painter’s awareness of the limits of the support on which he works. From the photo it is possible to see how Riopelle applies the paint, squeezing it directly on the canvas from a tube or other container. He then uses a palette knife to spread the paint.

While the results may sometimes appear similar, Riopelle’s method was vastly different from that of the Abstract Expressionists, and in particular the Action Painters, a group who saw the canvas as (in the words of the American critic Harold Rosenberg) an “arena in which to act.” Pollock’s way of moving within the physical space of the work created an unprecedented intimacy between the artist and the painted surface. Riopelle, for his part, adhered to a more conventional relationship, which placed the painter at a distance from his canvas, allowing him a certain perspective from which to contemplate rather than act.

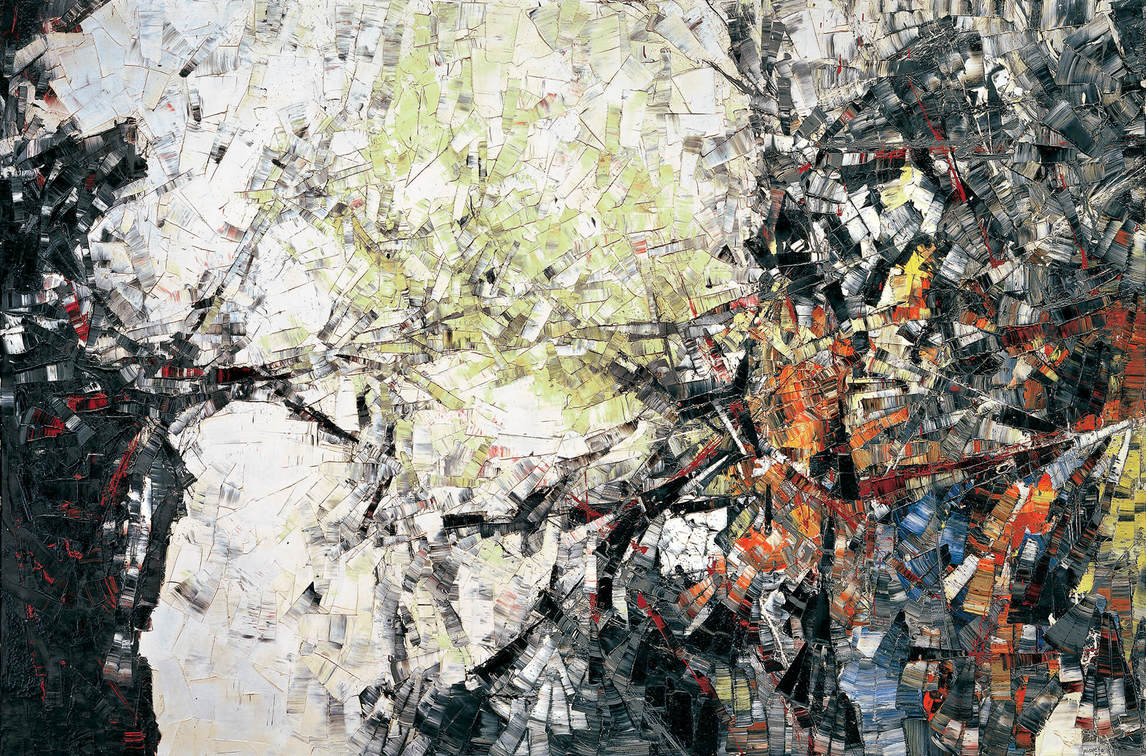

Riopelle’s Spain (Espagne), 1951, and Pollock’s Number 1A, 1948, are alike in their vividness and animation—both brim with vital energy and evoke a sense of freedom. Yet, although they seem closely related as acts of artistic expression, the creative means employed by the two artists to achieve these results are very different. Riopelle noted of Pollock, whom he met only twice in 1955: “I don’t feel any relationship with him at all.” Riopelle was right.

The Creation of a World

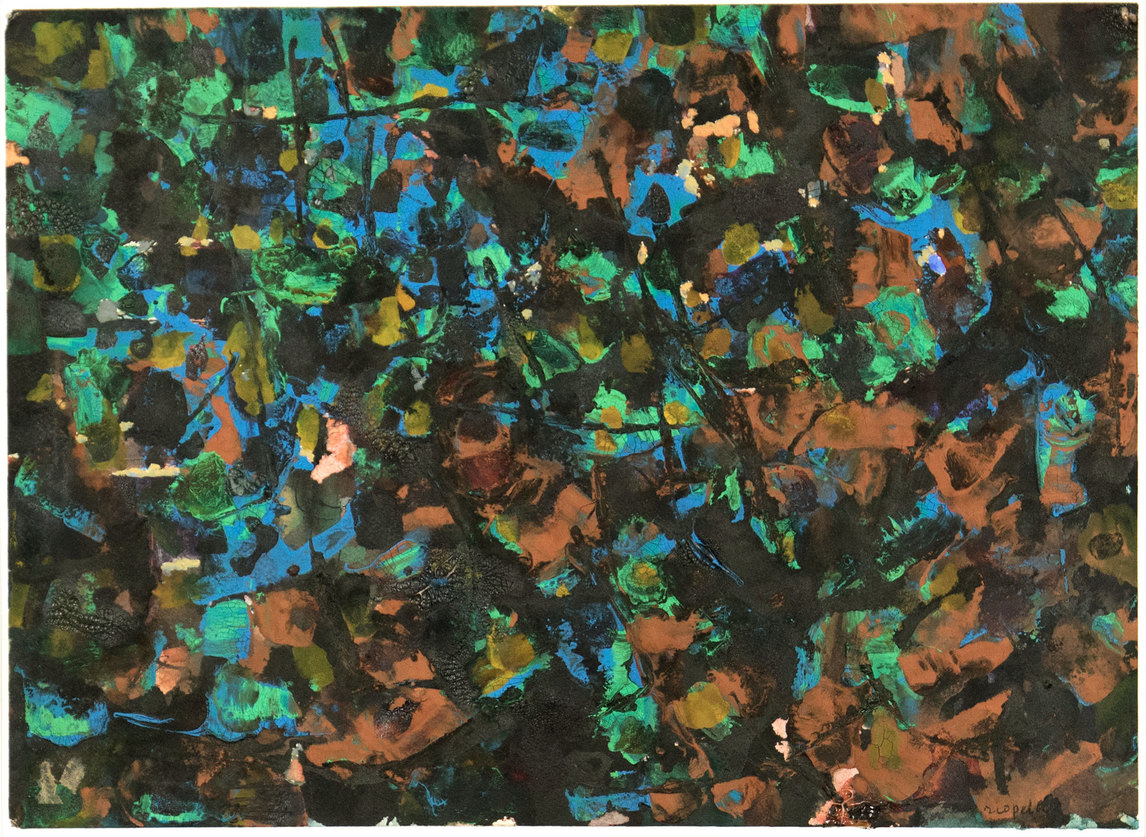

If Riopelle’s interactions with automatism, Lyrical Abstraction, and Abstract Expressionism prove anything, it is that he learned how to create, and show to the viewer, a world that was entirely his own. By distancing himself from these art movements of the mid-twentieth century, he followed a path of his individual design. Rather than imitate nature as so many artists had done before him, he wished to draw from it and create his own world, a place that could exist between abstraction and figuration. Here, illustrated by a work such as Austria III (Autriche III) from 1954, the artist is inspired by nature without having to distinctly picture it.

From an early age Riopelle learned to establish this critical distance between himself and those around him. His first move toward abstraction and away from academicism was the result of an attempt to picture water exactly as he saw it. It was precisely by trying to reproduce “the movement, the reflections of light, and the transformation of volumes under the prism of water” that firmly separated Riopelle from the academic approach of his teacher Henri Bisson (1900–1973) in favour of a more instinctive and expressive artistic practice. Likewise, as he delved deeper and deeper into abstraction, he did so not as a means to walk away from reality, but as a means to ground himself more firmly within it. For Riopelle, the relationship between abstraction and figuration is uncomplicated. It is a river that flows both ways.

The French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy’s observations about creation can be applied to Riopelle. As Nancy writes, “Art is always the art of making a world.” Riopelle succeeded in creating such a world, and he made this world easily accessible and allowed us throughout his career to play within it. Yet, at the same time, he knew how to explore it for himself, from the inside, and on his own terms.

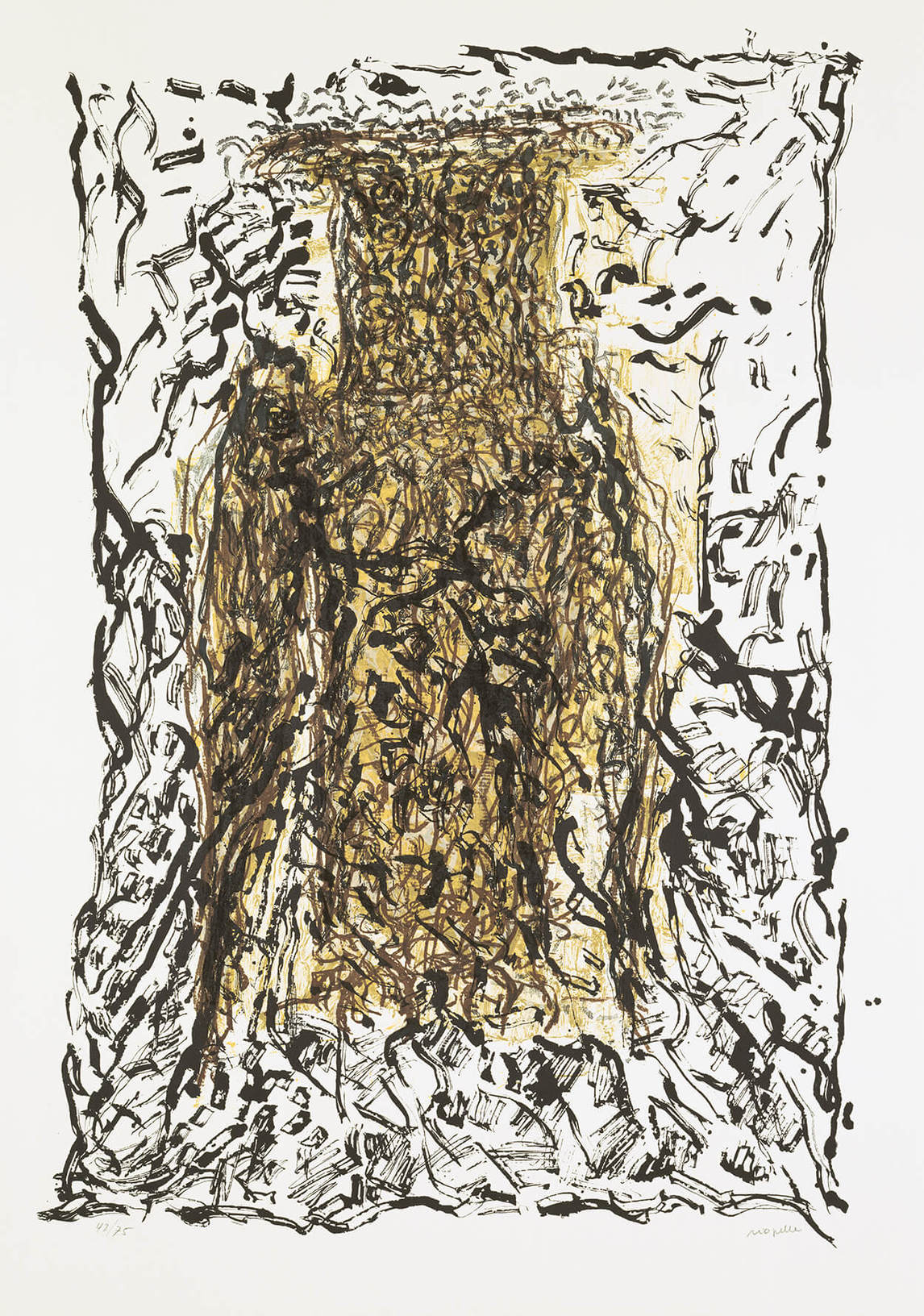

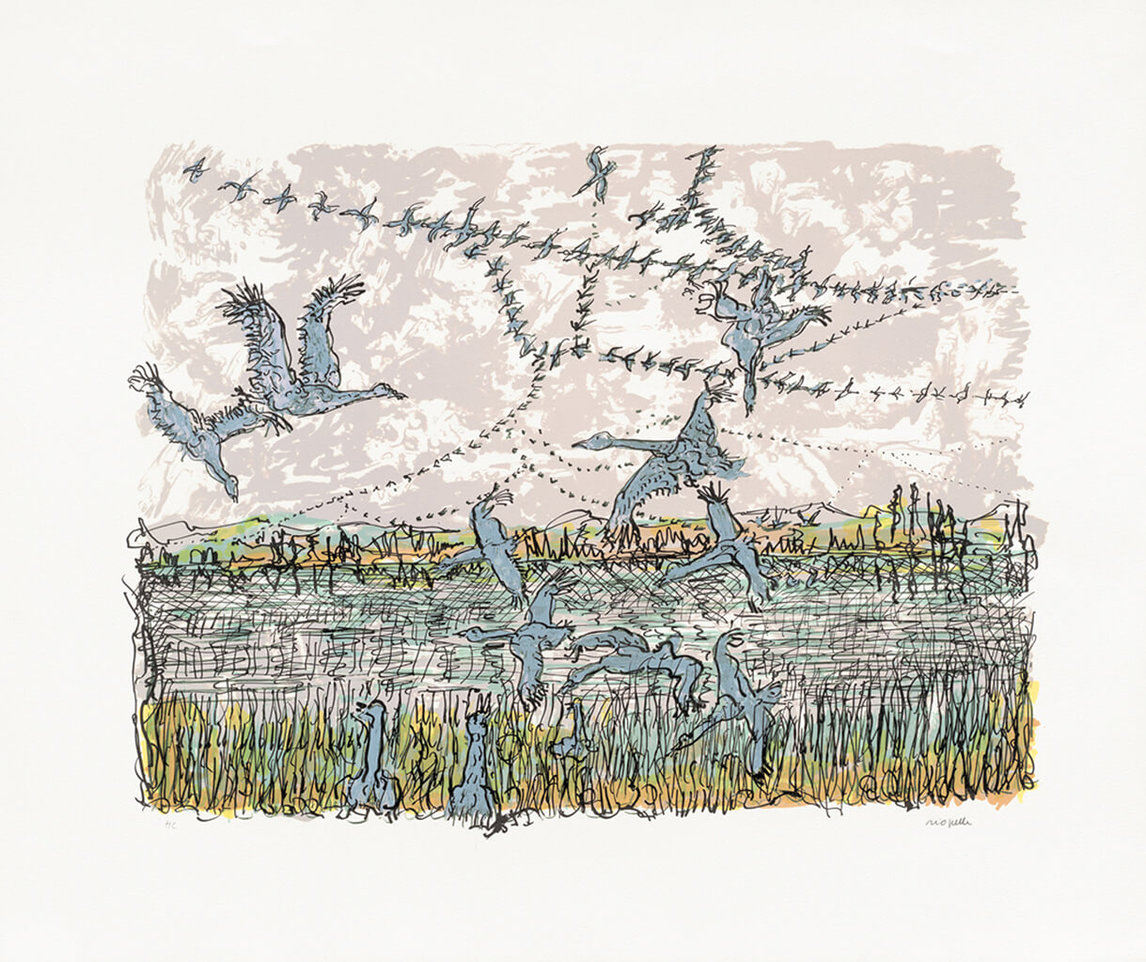

In Riopelle’s later works, such as Owl VII (Hibou VII), 1970, and The Goose Hunt (Chasse au Oies), 1981, the artist shows us the imaginative and distinct possibilities of the creative world he envisioned. In these paintings we see the culmination of Riopelle’s influences arrive at a focal point where abstraction and figuration meet in unique and uncomplicated ways. It is of course impossible not to see the owl pictured, or the snow geese repeated in a jumble quite reminiscent of the seasonal congregation that floods the sky, however, there is so much more to these pictures than meets the eye. In them expressions of wind, the currents of air that guide and lift the birds beyond our reach, the traces of the earth left in the deep brown hues painted against a stark white background, or the great movements of the earth itself, all converge and are represented in ways only available to an artist deeply engulfed by the world around him. In the end, Riopelle understood that his painting moved in concert with nature, rather than seeking to replace it.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements